Vera Krasovskaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Ballets Trockedero De Monte Carlo

Le Lac des Cygnes (Swan Lake), Act II Saturday, March 14, 2020, 8pm Sunday, March 15, 2020, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Les Ballet Trockadero de Monte Carlo Featuring Ludmila Beaulemova Maria Clubfoot Nadia Doumiafeyva Helen Highwaters Elvira Khababgallina Irina Kolesterolikova Varvara Laptopova Grunya Protozova Eugenia Repelskii Alla Snizova Olga Supphozova Maya Thickenthighya Minnie van Driver Guzella Verbitskaya Jacques d’Aniels Boris Dumbkopf Nicholas Khachafallenjar Marat Legupski Sergey Legupski Vladimir Legupski Mikhail Mudkin Boris Mudko Mikhail Mypansarov Yuri Smirnov Innokenti Smoktumuchsky Kravlji Snepek William Vanilla Tino Xirau-Lopez Tory Dobrin Artistic Director Isabel Martinez Rivera Associate Director Liz Harler General Manager Cal Performances’ 2019–20 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 21 22 PLAYBILL PROGRAM Le Lac des Cygnes (Swan Lake), Act II Music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Choreography after Lev Ivanovich Ivanov Costumes by Mike Gonzales Décor by Clio Young Lighting by Kip Marsh Benno: Mikhail Mypansarov (friend and confidant to) Prince Siegfried: Vladimir Legupski (who falls in love with) Alla Snizova (Queen of the) Swans Ludmila Beaulemova, Maria Clubfoot, Nadia Doumiafeyva, Minnie van Driver, Elvira Khababgallina, Grunya Protozova, Maya Thickenthighya, Guzella Verbitskaya (all of whom got this way because of) Von Rothbart: Yuri Smirnov (an evil wizard who goes about turning girls into swans) INTERMISSION Pas de Deux or Modern Work to be Announced Le Grand Pas de Quatre Music by Cesare Pugni Choreography after Jules -

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon Du Diable

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Edited and Introduced by Robert Ignatius Letellier Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable, Edited by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3608-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3608-1 Cesare Pugni in London (c. 1845) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................... ix Esmeralda Italian Version La corte del miracoli (Introduzione) .......................................................................................... 2 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................. 5 Sposalizio di Esmeralda ............................................................................................................. 6 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................ -

2013| 2014 Community Programs Atlanta Ballet's

2013| 2014 COMMUNITY PROGRAMS ATLANTA BALLET’S NUTCRACKER STUDY GUIDE PRESENTED BY DEAR EDUCATOR Atlanta Ballet and Atlanta Ballet Centre for Dance Education are committed to bringing you and your students the highest quality educational programs available. We continually strive to meet the ever-growing needs of students and the educational community. Please take a moment, after viewing the ballet and using the study guide, to complete the survey enclosed at the end of this guide. Your feedback is the only way we can continue to deliver high quality programs. This study guide was designed to acquaint both you and your students with Atlanta Ballet’s Nutcracker, as well as provide an interdisciplinary approach to teaching your existing curriculum and skills. This study guide was prepared by Atlanta Ballet staff members with educational backgrounds. Every attempt was made to ensure that this study guide can be used to enhance your existing curriculum. We hope both you and your students enjoy the educational experience of Atlanta Ballet and have fun along the way! Sharon Story Nicole Kedaroe Dean, Centre for Dance Education Community Division Manager TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Information and Teacher Resources Suggested Resources 4 Curriculum Connections 5 Synopsis of the Ballet 6 The Composer 7 The Choreographer 8 Choreographer History 9 History of the Nutcracker 10 History of Atlanta Ballet 11-12 History of Ballet 13 History of the Fox 14 Who’s Who in the Ballet 15 Nutcracker Vocabulary 16 Student Activities Creating a Ballet 17 Pantomime 18* Answer This 19 Who am I? 20 Extra, Extra 21 Character Education 22-23 Nutcracker Matching Quiz 24 Word Search 25 Drawing Activities 26 *This page is from the Ballet Workbook Series The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, E.T.A. -

Scaramouche and the Commedia Dell'arte

Scaramouche Sibelius’s horror story Eija Kurki © Finnish National Opera and Ballet archives / Tenhovaara Scaramouche. Ballet in 3 scenes; libr. Paul [!] Knudsen; mus. Sibelius; ch. Emilie Walbom. Prod. 12 May 1922, Royal Dan. B., CopenhaGen. The b. tells of a demonic fiddler who seduces an aristocratic lady; afterwards she sees no alternative to killinG him, but she is so haunted by his melody that she dances herself to death. Sibelius composed this, his only b. score, in 1913. Later versions by Lemanis in Riga (1936), R. HiGhtower for de Cuevas B. (1951), and Irja Koskkinen [!] in Helsinki (1955). This is the description of Sibelius’s Scaramouche, Op. 71, in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet. Initially, however, Sibelius’s Scaramouche was not a ballet but a pantomime. It was completed in 1913, to a Danish text of the same name by Poul Knudsen, with the subtitle ‘Tragic Pantomime’. The title of the work refers to Italian theatre, to the commedia dell’arte Scaramuccia character. Although the title of the work is Scaramouche, its main character is the female dancing role Blondelaine. After Scaramouche was completed, it was then more or less forgotten until it was published five years later, whereupon plans for a performance were constantly being made until it was eventually premièred in 1922. Performances of Scaramouche have 1 attracted little attention, and also Sibelius’s music has remained unknown. It did not become more widely known until the 1990s, when the first full-length recording of this remarkable composition – lasting more than an hour – appeared. Previous research There is very little previous research on Sibelius’s Scaramouche. -

Spring Performances Celebrate Class of 2018

Fall 2018 Spring Performances Celebrate Class of 2018 The Morris and Elfriede Stonzek Spring Performances, presented last May, served as a fitting celebration of the 2018 graduating class and a wonderful way to kick off Memorial Day weekend. In keeping with tradition, the performances opened with a presentation of the fifteen seniors who would receive their diplomas the following week—HARID’s largest-ever graduating class. Alex Srb photo © Srb photo Alex The program opened with The Fairy Doll Pas de Trois, staged by Svetlana Osiyeva and Meelis Pakri. Catherine Alex Srb © Alex Doherty sparkled as the fairy doll, in an exquisite pink tutu, while David Rathbun and Jaysan Stinnett (cast as the two A scene from the Black Swan Pas de Deux, Swan Lake, Act III pierrots competing for her attention) accomplished the challenging technical elements of the ballet while endearingly portraying their comedic characters. The next work on the program was the premiere of It Goes Without Saying, choreographed for HARID by resident choreographer Mark Godden. Set to music by Nico Muhly and rehearsed by Alexey Kulpin, this work stretched the artistic scope of the dancers by requiring them to speak on stage and move in unison to music that is not always melodically driven. The ballet featured a haunting pas de Alex Srb photo © Srb photo Alex deux, performed maturely by Anna Gonzalez and Alexis Alex Srb © Alex Valdes, and a spirited, playful duet for dancers Tiffany Chatfield and Chloe Crenshaw. The Fairy Doll Pas de Trois The second half of the program featured Excerpts from Swan Lake, Acts I and III. -

Basic Principles of Classical Ballet: Russian Ballet Technique Free Download

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CLASSICAL BALLET: RUSSIAN BALLET TECHNIQUE FREE DOWNLOAD Agrippina Vaganova,A. Chujoy | 175 pages | 01 Jun 1969 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486220369 | English | New York, United States Classical Ballet Technique Vaganova was a student at the Imperial Ballet School in Saint Petersburggraduating in Basic Principles of Classical Ballet: Russian Ballet Technique dance professionally with the school's parent company, the Imperial Russian Ballet. Vaganova —not only a great dancer but also the teacher of Galina Ulanova and many others and an unsurpassed theoretician. Balanchine Method dancers must be extremely fit and flexible. Archived from the original on The stem of aplomb is the spine. Refresh and try again. A must Basic Principles of Classical Ballet: Russian Ballet Technique for any classically trained dancer. Enlarge cover. Can I view this online? See Article History. Jocelyn Mcgregor rated it liked it May 28, No trivia or quizzes yet. Black London. The most identifiable aspect of the RAD method is the attention to detail when learning the basic steps, and the progression in difficulty is often very slow. En face is the natural direction for the 1st and 2nd positions and generally they remain so. Trivia About Basic Principles This the book that really put the Vaganova method of ballet training on the map-a brave adventure, and a truly important book. Helps a lot during my russian classes. Through the 30 years she spent teaching ballet and pedagogy, Vaganova developed a precise dance technique and system of instruction. Rather than emphasizing perfect technique, ballet dancers of the French School focus instead on fluidity and elegance. -

Russian Theatre Festivals Guide Compiled by Irina Kuzmina, Marina Medkova

Compiled by Irina Kuzmina Marina Medkova English version Olga Perevezentseva Dmitry Osipenko Digital version Dmitry Osipenko Graphic Design Lilia Garifullina Theatre Union of the Russian Federation Strastnoy Blvd., 10, Moscow, 107031, Russia Tel: +7 (495) 6502846 Fax: +7 (495) 6500132 e-mail: [email protected] www.stdrf.ru Russian Theatre Festivals Guide Compiled by Irina Kuzmina, Marina Medkova. Moscow, Theatre Union of Russia, April 2016 A reference book with information about the structure, locations, addresses and contacts of organisers of theatre festivals of all disciplines in the Russian Federation as of April, 2016. The publication is addressed to theatre professionals, bodies managing culture institutions of all levels, students and lecturers of theatre educational institutions. In Russian and English. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. The publisher is very thankful to all the festival managers who are being in constant contact with Theatre Union of Russia and who continuously provide updated information about their festivals for publication in electronic and printed versions of this Guide. The publisher is particularly grateful for the invaluable collaboration efforts of Sergey Shternin of Theatre Information Technologies Centre, St. Petersburg, Ekaterina Gaeva of S.I.-ART (Theatrical Russia Directory), Moscow, Dmitry Rodionov of Scena (The Stage) Magazine and A.A.Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum. 3 editors' notes We are glad to introduce you to the third edition of the Russian Theatre Festival Guide. -

The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

Thursday, October 1, 2015, 8pm Friday, October 2, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 3, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 4, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra Gavriel Heine, Conductor The Company Diana Vishneva, Nadezhda Batoeva, Anastasia Matvienko, Sofia Gumerova, Ekaterina Chebykina, Kristina Shapran, Elena Bazhenova Vladimir Shklyarov, Konstantin Zverev, Yury Smekalov, Filipp Stepin, Islom Baimuradov, Andrey Yakovlev, Soslan Kulaev, Dmitry Pukhachov Alexandra Somova, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Tamara Gimadieva, Sofia Ivanova-Soblikova, Irina Prokofieva, Anastasia Zaklinskaya, Yuliana Chereshkevich, Lubov Kozharskaya, Yulia Kobzar, Viktoria Brileva, Alisa Krasovskaya, Marina Teterina, Darina Zarubskaya, Olga Gromova, Margarita Frolova, Anna Tolmacheva, Anastasiya Sogrina, Yana Yaschenko, Maria Lebedeva, Alisa Petrenko, Elizaveta Antonova, Alisa Boyarko, Daria Ustyuzhanina, Alexandra Dementieva, Olga Belik, Anastasia Petushkova, Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Elena Androsova, Svetlana Ivanova, Ksenia Dubrovina, Ksenia Ostreikovskaya, Diana Smirnova, Renata Shakirova, Alisa Rusina, Ekaterina Krasyuk, Svetlana Russkikh, Irina Tolchilschikova Alexey Popov, Maxim Petrov, Roman Belyakov, Vasily Tkachenko, Andrey Soloviev, Konstantin Ivkin, Alexander Beloborodov, Viktor Litvinenko, Andrey Arseniev, Alexey Atamanov, Nail Enikeev, Vitaly Amelishko, Nikita Lyaschenko, Daniil Lopatin, Yaroslav Baibordin, Evgeny Konovalov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vadim Belyaev, Oleg Demchenko, Alexey Kuzmin, Anatoly Marchenko, -

Download Booklet

Sergey PROKOFIEV Romeo and Juliet Complete ballet Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop CD 1 75:03 CD 2 69:11 Sergey Prokofiev (1891–1953) Romeo and Juliet Act I Act II (contd.) It is a measure of the achievement of Prokofiev’s most ballet’). Rejecting the supposedly empty-headed 1 Introduction 2:39 1 Romeo at Friar Laurence’s 2:50 well-loved stage work that today we take for granted the confections of Marius Petipa (legendary choreographer of 2 Romeo 1:35 2 Juliet at Friar Laurence’s 3:16 concept of a narrative full-length ballet, in which every Tchaikovsky’s ballets), Radlov and his choreographers dance and action advances its story. Indeed, we are now aimed to create ballets with realistic narratives and of 3 The Street Wakens 1:33 3 Public Merrymaking 3:23 so familiar with this masterpiece that it is easy to overlook psychological depth, meanwhile teaching dancers how to 4 4 Morning Dance 2:12 Further Public Festivities 2:32 how audacious was the concept of translating so verbal a convey the thoughts and motivations of the characters 5 The Quarrel 1:43 5 Meeting of Tybalt and Mercutio 1:56 drama as Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet into a full- they portrayed. As artistic director of the Leningrad State 6 The Fight 3:43 6 The Duel 1:27 length ballet. Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet (formerly the 7 The Duke’s Command 1:21 7 Death of Mercutio 2:31 We largely owe its existence to Sergey Radlov, a Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, but now widely known by the 8 Interlude 1:54 8 Romero Decides to Avenge Mercutio 2:07 disciple of the revolutionary theatre director Vsevolod abbreviation Akopera), Radlov directed two early 9 At the Capulets’ 9 Finale 2:07 Meyerhold. -

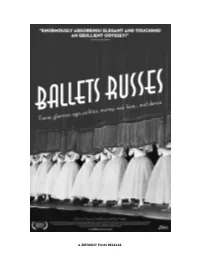

Ballets Russes Press

A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE THEY CAME. THEY DANCED. OUR WORLD WAS NEVER THE SAME. BALLETS RUSSES a film by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller Unearthing a treasure trove of archival footage, filmmakers Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine have fashioned a dazzlingly entrancing ode to the rev- olutionary twentieth-century dance troupe known as the Ballets Russes. What began as a group of Russian refugees who never danced in Russia became not one but two rival dance troupes who fought the infamous “ballet battles” that consumed London society before World War II. BALLETS RUSSES maps the company’s Diaghilev-era beginnings in turn- of-the-century Paris—when artists such as Nijinsky, Balanchine, Picasso, Miró, Matisse, and Stravinsky united in an unparalleled collaboration—to its halcyon days of the 1930s and ’40s, when the Ballets Russes toured America, astonishing audiences schooled in vaudeville with artistry never before seen, to its demise in the 1950s and ’60s when rising costs, rock- eting egos, outside competition, and internal mismanagement ultimately brought this revered company to its knees. Directed with consummate invention and infused with juicy anecdotal interviews from many of the company’s glamorous stars, BALLETS RUSSES treats modern audiences to a rare glimpse of the singularly remarkable merger of Russian, American, European, and Latin American dancers, choreographers, composers, and designers that transformed the face of ballet for generations to come. — Sundance Film Festival 2005 FILMMAKERS’ STATEMENT AND PRODUCTION NOTES In January 2000, our Co-Producers, Robert Hawk and Douglas Blair Turnbaugh, came to us with the idea of filming what they described as a once-in-a-lifetime event. -

Nutcracker Program 2014Opt.Pdf

Nutcrackerthe SEISKAYA BALLET Nutcrackerthe Casse Noisette Early in 1891 the legendary composer Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky received a commission from the Imperial Theatre Directorate at St. Petersburg to compose a one-act lyric opera together with a ballet for presentation during the following season. Accepting Tchaikovsky’s choice of sub- ject for the opera, the Theatre Directorate selected Alexandre Dumas’ French adaptation of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s tale, The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, for the ballet. Tchaikovsky was not pleased with the subject selection because he felt it did not lend itself to theatrical presentation and was therefore quite unsuited to serve as a scenario for a ballet. Both the opera and ballet were presented on December 18, 1892. The ballet, conducted by Ric- cardo Drigo, was received somewhat unfavorably. Dance historians have attributed this to the Nutcracker’s unusual story, which was quite different from the romantic tales normally presented. The Nutcracker choreography was begun by the redoubtable Marius Petipa. The balance of the work was taken up by his assistant Leon Ivanov when Petipa fell ill. According to historical accounts, when the ballet was finally produced, Petipa refused to have his name linked with it, feeling his own part in its creation was insufficient to be publicly announced. However, dance historians have recognized his contribu- tion, and the original choreography is generally credited to both Petipa and Ivanov. First presented in Western Europe by the Sadler’s Wells Ballet at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London, January 30, 1934, the production was staged by Nicholas Sergeyev after the original Petipa-Ivanov version. -

A Thousand Encores: the Ballets Russes in Australia

PUBLICITY MATERIAL A Thousand Encores: The Ballets Russes in Australia CONTACT PRODUCTION COMPANY flaming star films 7/32 George Street East Melbourne 3002 Tel: +61 3 9419 8097 Mob: +61 (0)417 107 516 Email: [email protected] EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Sharyn Prentice WRITER / DIRECTOR Mandy Chang PRODUCERS Marianne Latham / Lavinia Riachi EDITOR Karin Steininger Ballets Russes dancer Anna Volkova as the Golden Cockerel in Fokine's Le Coq d'Or A Thousand Encores: The Ballets Russes in Australia SHORT SYNOPSIS A Thousand Encores is the story of how the greatest ballet company of the 20th Century - the celebrated Ballets Russes, came to Australia and awoke a nation, transforming the cultural landscape of conservative 30’s Australia, leaving a rich legacy that lasts to this day. EXTENDED SYNOPSIS A Thousand Encores tells the surprising and little known story of how, over 70 years ago, an extraordinary company of dancers made a deep impact on our cultural heritage. In 1936, the celebrated Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo stepped off a boat into the bright Australian sunlight. With exotic sets and costumes designed by cutting edge-artists and avant-garde music by great composers like Stravinsky, the Ballets Russes inspired a nation and transformed our cultural landscape. Over five years from 1936 to 1940 they came to Australia three times, winning the hearts and minds of Australian audiences, inspiring a generation of our greatest artists - Grace Cossington Smith, Jeffrey Smart and Sidney Nolan - and ultimately sowing the seeds for Australian ballet today. The story is bought alive using a rich archival resource. Australia has the biggest collection of Ballets Russes footage in the world and an impressive photographic record - the most famous pictures taken by a young Max Dupain.