Carl Anderson Remarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liturgical Calendar 2007 for the Dioceses of the United States of America

LITURGICAL CALENDAR 2007 FOR THE DIOCESES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Committee on the Liturgy United States Conference of Catholic Bishops 2 © 2006 United States Conference of Catholic Bishops 2 3 Introduction Each year the Secretariat for the Liturgy of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops publishes the Liturgical Calendar for the Dioceses of the United States of America. This calendar is used by authors of ordines and other liturgical aids published to foster the celebration of the liturgy in our country. The calendar is based upon the General Roman Calendar, promulgated by Pope Paul VI on February 14, 1969, subsequently amended by Pope John Paul II, and the Particular Calendar for the Dioceses of the United States of America, approved by the National Conference of Catholic Bishops.1 The General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 2002, reminds us that in the cycles of readings and prayers proclaimed throughout the year in the sacred liturgy “the mysteries of redemption are recalled in the Mass in such a way that they are in some way made present.” Thus may each celebration of the Holy Eucharist which is served by this calendar be for the Church in all the dioceses of the United States of America “ the high point of the action by which God sanctifies the world in Christ and of the worship that the human race offers to the Father, adoring him through Christ, the Son of God, in the Holy Spirit.”2 Monsignor James P. Moroney Executive Director USCCB Secretariat for the Liturgy 1 For the significance of the several grades or kinds of celebrations, the norms of the Roman Calendar should be consulted (cf. -

Cathedral of Saint Joseph, Manchester, New Hampshire

Cathedral of Saint Joseph Manchester, New Hampshire Sacred and Liturgical Music Program 2019 – 2020 (Liturgical Year C – A) Most Reverend Peter A. Libasci, D.D. Tenth Bishop of Manchester Very Reverend Jason Y. Jalbert Cathedral Rector Vicar General Director of the Office for Worship Mr. Eric J. Bermani, DMin (Cand.) Diocesan & Cathedral Director of Music/Organist 2 Music at The Cathedral of Saint Joseph 2019-2020 Welcome to a new season of sacred music at The Cathedral of Saint Joseph. Music has always played an important role in the life of this Cathedral parish. Included in this booklet is a listing of music to be sung by assembly, cantors and the Cathedral Choir, highlighting each Sunday, feast or liturgical season. “Sing to the Lord a new song: sing to the Lord all the earth. Sing to the Lord, and bless his Name: proclaim the good news of his salvation from day to day.” Psalm 96:1-2 “When there is devotional music, God is always at hand with His gracious presence.” J.S. Bach “Music for the liturgy must be carefully chosen and prepared.” Sing to the Lord (Music in Divine Worship) Article 122 “The treasury of sacred music is to be preserved and fostered with great care. Choirs must be diligently developed, especially in cathedral churches.” Constitution of the Sacred Liturgy, Article 114 “Music is the means of recapturing the original joy and beauty of Paradise.” St. Hildegard von Bingen “All other things being equal, Gregorian chant holds pride of place because it is proper to the Roman Liturgy. -

Liturgical Press Style Guide

STYLE GUIDE LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org STYLE GUIDE Seventh Edition Prepared by the Editorial and Production Staff of Liturgical Press LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design by Ann Blattner © 1980, 1983, 1990, 1997, 2001, 2004, 2008 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Printed in the United States of America. Contents Introduction 5 To the Author 5 Statement of Aims 5 1. Submitting a Manuscript 7 2. Formatting an Accepted Manuscript 8 3. Style 9 Quotations 10 Bibliography and Notes 11 Capitalization 14 Pronouns 22 Titles in English 22 Foreign-language Titles 22 Titles of Persons 24 Titles of Places and Structures 24 Citing Scripture References 25 Citing the Rule of Benedict 26 Citing Vatican Documents 27 Using Catechetical Material 27 Citing Papal, Curial, Conciliar, and Episcopal Documents 27 Citing the Summa Theologiae 28 Numbers 28 Plurals and Possessives 28 Bias-free Language 28 4. Process of Publication 30 Copyediting and Designing 30 Typesetting and Proofreading 30 Marketing and Advertising 33 3 5. Parts of the Work: Author Responsibilities 33 Front Matter 33 In the Text 35 Back Matter 36 Summary of Author Responsibilities 36 6. Notes for Translators 37 Additions to the Text 37 Rearrangement of the Text 37 Restoring Bibliographical References 37 Sample Permission Letter 38 Sample Release Form 39 4 Introduction To the Author Thank you for choosing Liturgical Press as the possible publisher of your manuscript. -

The Tradition of the Red Mass Was Begun by Pope Innocent IV in 1243

Mass with Bishop Timothy L. Doherty followed by a dinner for legal professionals and a presentation by Notre Dame Law Professor Richard W. Garnett The tradition of the Red Mass was begun by Pope Innocent IV in 1243 for the Ecclesial Judical Court asking the invocation of the Holy Spirit as a source of wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude and strength for the coming term of the court. The color red signifies the Holy Spirit and martyrdom. St. Thomas More is the patron saint of lawyers. The Diocese of Lafayette-in-Indiana will celebrate the fifth annual Red Mass on Monday, October 5, 2020, at the Cathedral of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception in Lafayette at 5:30 pm. All government officials (federal, state, local levels, executive, legislative, judicial branches), attorneys, paralegals, law students and their spouses are cordially invited to attend. One does not have to be Catholic to join us in prayer and fellowship for the legal community. The Red Mass is a tradition in the Catholic Church which dates back to the 13th century. The first Red Mass is believed to have been celebrated in the Cathedral of Paris in 1245, and thereafter the tradition spread throughout Europe. A Red Mass was initially celebrated to mark the beginning of the annual term of the courts but can be held at other times. The word “red” was originally used to describe the Mass in 1310, because the justices of the English Supreme Court wore scarlet robes. Over time the “Red” Mass came to have a deeper theological meaning, with red symbolizing the “tongues of fire” that descended upon the Apostles at Pentecost bestowing the gifts of the Spirit. -

The Church Today, October 17, 2016

CHURCH TODAY Volume XLVII, No. 10 www.diocesealex.org Serving the Diocese of Alexandria, Louisiana Since 1970 October 17, 2016 O N T H E INSIDE Welcome Bishop David Talley, coadjutor for the Diocese of Alexandria Pope Francis has appointed Bishop David P. Talley, auxiliary bishop of the Atlanta Archdiocese, to serve the people of the Diocese of Alexandria, Louisiana, as coadjutor bishop to Bishop Ronald P. Herzog. Read more on page 3. Bishop’s Golf Tournament raises more than $30,000 for seminarian education Twenty-seven teams came out to enjoy the beautiful fall weather and to play a round of golf with friends at the annual Invitational Bishop’s Golf Tourna- Catch up with Jesus ment Oct. 10. More than $30,000 was raised. See pages 10-11. Students from St. Joseph Catholic School in Plaucheville wear their “Catch Up with Jesus” fall festival t-shirts for their school fair held Oct. 8-9. Schools and churches throughout the diocese have hosted fall fairs and festivals during October. See pages 12-13 for more celebrations during the month of October. PAGE 2 CHURCH TODAY OCTOBER 17, 2016 Presidential election politics have sunk to an all-time low Critics say candidates need to step out of the gutter; focus on more pressing needs By Rhina Guidos dent. Catholic News Service In response, two members of the advisory group, Father (CNS) -- Christopher J. Hale, Frank Pavone, national director executive director for Washing- of Priests for Life, and Janet Mo- ton’s Catholics in Alliance for the rana, co-founder of the Silent No Common Good, said the Oct. -

Holy Family Catholic Church 25Th Sunday in Ordinary Time

Holy Family Catholic Church 25th Sunday in Ordinary Time Mass times , Intentions & Readings INFANT BAPTISMS: Parents are required to contact the Parish Office for the date of the next baptismal class, September 20th –26th to register for the class, and to schedule a baptism. Parents must be registered in the Parish for at least three months prior to the request. The class must be Sunday September 20th , 2015 completed one month prior to the baptism. Parents must Twenty-Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time call to confirm the time and date with the Priest or Wis 2:12, 17-20; Ps 54; Jas 3:16—4:3; Mk 9:30-37 Deacon who will be celebrating the baptism, two weeks 8:30 AM † Eden Grace Downing prior to the baptism to make sure everything is ready. Anniversary of Death Baptisms celebrated during Mass will only be on the By Pat Downing third weekend of the month. Outside of Mass, baptism 10:30 AM Rosary in the Chapel will be celebrated by a Deacon on all other weekends. For the godparent/sponsor please obtain a copy of the 11:00 AM People of the Parish requirements from the Parish Office, or at www.holyfamilylawton.org. Click on Baptism under 1:00 PM † Trinidad Barber Sacraments. By Hispanic Ministries BAUTIZO PARA LOS INFANTES: Los padres necesi- tan ponerse en contacto con la oficina para saber la fe- Monday September 21st , 2015 cha de la próxima clase de preparación para el Bautizo, Saint Matthew, Apostle and Evangelist registrarse para tomar la clase y fijar la fecha del Eph 4:1-7, 11-13; Ps 19; Mt 9:9-13 Bautizo. -

Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland

Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland 510 Ocean Avenue Telephone: (207) 321-7810 Portland, ME 04103-4936 Facsimile: (207) 773-0182 Office of Communications WEEKLY MAILING August 28, 2014 [email protected] I. Office of the Moderator of the Curia Varia (September 2014) II. Office of the Chancellor Diocesan Directory Changes III. Office of Communications Special Collection, Donation Information for Relief in the Middle East Bishop Deeley to Lead Special Pilgrimage to Quebec City (October 3-5) Blue Mass (September 14 in Lewiston) Red Mass (September 26 in Portland) IV. Office of Ministerial Services 2014 Priests’ Annual Retreat (October 12-16 in Biddeford) V. Office of Lifelong Faith Formation Catechetical Sunday (September 21) Parish Life Conference (September 27 in Lewiston) Bible-in-a-Day Workshop (October 18 in Portland) Rachel’s Vineyard Retreat (November 14-16 in Southern Maine) World Meeting of Families (September 2015 in Philadelphia) VI. Office of Human Resources Mason (Diocesan Construction) Building and Grounds Manager (Prince of Peace Parish) Part-Time Custodian (Good Shepherd Parish) Part-Time Eighth-Grade Teacher (St. James Catholic School, Biddeford) VII. Choose Life Maine Pro-Life License Plates in Maine VIII. The Presence Radio Network Bulletin Item for the Weekend of September 6-7 For updated news and features from the diocese, visit: www.portlanddiocese.org. For Adobe Reader, visit: get.adobe.com/reader. Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland 510 Ocean Avenue Telephone: (207) 773-6471 Portland, ME 04103-4936 Facsimile: (207) 773-0182 Office of the Moderator of the Curia To: All Priests, Deacons, Seminarians and Pastoral Associates Date: Thursday, August 28, 2014 Re: VARIA – SEPTEMBER 2014 General Announcements Chancery Hours – Regular Hours: Beginning Tuesday, September 2, 2014, the Chancery will be open Monday through Friday from 9:00 a.m. -

Download The

Inside WeST RIVeR Getting the Nation Back on Track, page 2 Advent Reconciliation, page 3 Handling Ashes Following Cremation, page 5 Priority Plan Moves Forward, pages 12-13 Diocesan Necrology, pages 16-17 Informing Catholics in Western South Dakota since May 1973 Oglala Centennial, page 21 Diocese of Rapid City Volume 45 Number 7 www.rapidcitydiocese.org CNovemberatholic 2016 South Dakota “Rejoice always. Pray without ceasing. In all circumstances give thanks, for this is the will of God for you in Christ Jesus. Do not quench the Spirit” (1 Thes 5:16-19). Though there are many challenges in our his countless blessings and pray for a new world to face, we can be assured the Lord is outpouring of the Holy Spirit in our lives. with us in every moment. This is the greatest Know that my Thanksgiving Mass will of blessings. The celebration of Thanksgiving be offered for you and your intentions. As reminds us of the importance to stop and we give the Lord thanks, may he continue reflect upon our many blessings, the great to bless you abundantly this day and abundance around us and the One who always. Wishing you peace and joy in provides it all. On this Thanksgiving Day, we Christ. turn to the Lord in prayer and gratitude for + Bishop Robert Gruss Coming together as faithful citizens for the common good representatives, would do well to to working with President-elect ment to domestic religious liberty, ARCHBISHOP JOSEPH E. KURTZ remember the words of Pope Trump to protect human life from ensuring people of faith remain PRESIDENT, USCCB Francis when he addressed the its most vulnerable beginning to free to proclaim and shape our WASHINGTON — The United States Congress last year, its natural end. -

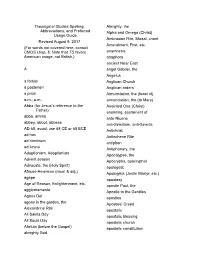

Theological Studies Spelling, Abbreviations, and Preferred Usage

Theological Studies Spelling, Almighty, the Abbreviations, and Preferred Alpha and Omega (Christ) Usage Guide Ambrosian Rite, Missal, chant Revised August 9, 2017 Amendment, First, etc. (For words not covered here, consult CMOS chap. 8. Note that TS favors anamnesis American usage, not British.) anaphora ancient Near East A angel Gabriel, the Angelus a fortiori Anglican Church a posteriori Anglican orders a priori Annunciation, the (feast of) a.m., p.m. annunciation, the (to Mary) Abba (for Jesus’s reference to the Anointed One (Christ) Father) anointing, sacrament of abba, amma ante-Nicene abbey, abbot, abbess anti-Semitism, anti-Semitic AD 68, avoid: use 68 CE or 68 BCE Antichrist ad hoc Antiochene Rite ad hominem antiphon ad limina Antiphonary, the Adoptionism, Adoptionists Apocalypse, the Advent season Apocrypha, apocryphal Advocate, the (Holy Spirit) apologetic African-American (noun & adj.) Apologists (Justin Martyr, etc.) agape apostasy Age of Reason, Enlightenment, etc. apostle Paul, the aggiornamento Apostle to the Gentiles Agnus Dei apostles agony in the garden, the Apostles’ Creed Alexandrine Rite apostolic All Saints Day apostolic blessing All Souls Day apostolic church Alleluia (before the Gospel) apostolic constitution almighty God apostolic exhortation (by a pope) beatific vision Apostolic Fathers Beatitudes, the Apostolic See Being (God) appendixes Beloved Apostle, the archabbot Beloved Disciple, the archangel Michael, the Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament archdiocese Benedictus Archdiocese of Seattle berakah (pl.: -

Red Mass Homily, 2020 – October 6, 2020 by Father John Mccartney

Red Mass Homily, 2020 – October 6, 2020 By Father John McCartney Today we come together to offer our annual “Red Mass,” for those who serve in the legal profession. We ask for God’s blessing upon all present and especially that the gifts of the Holy Spirit: wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety and fear of the Lord, will be bestowed upon you in your personal and in your professional lives. At this Red Mass we find ourselves in very unusual times. The year 2020 has not turned out as any of us would have expected. The year began with the impeachment and trial of the President. Immediately afterwards, we entered the pandemic which would grip our nation and our world, shutting down society all around the globe. For months now, political, racial and economic tensions have resulted in civil unrest throughout a great portion of our nation. Wildfires are now devastating the American West. And we find ourselves in the midst of a contentious presidential election with a Supreme Court nomination suddenly thrown in for good measure. If this were a novel, it would be considered too improbable to be published. Sometimes, when the way forward seems daunting and unclear, it is good to look back, to remember where we have come from, to get perspective on where we are, and to see where we are going. Two-hundred and thirty-two years ago, in the year 1788, this country was in the midst of a presidential election. It was our first, at the beginning of the new national government. -

2020 Red Mass Printable Worship

ADVOCATI CHRISTI THE FIFTH ANNUAL The Outreach to Catholic Lawyers, Advocati Christi, includes Catholic lawyers and judges who have entered into an elite fellow- RED MASS ship of those who are committed to both the legal profession and the profession of their faith. The membership includes seasoned Founding Fellows, Senior Fellows who act as mentors and guides, Fellows, and Fellows Elect who are in the process of becoming members. The Fellowship’s home is St. Paul Inside the Walls, the Catholic Center for Evangelization in the Diocese of Paterson, located in Madison, New Jersey. Come, Holy Ghost Text: LM with repeat; Veni, Creator Spiritus; attr. to Rabanus Maurus, 776-856, tr. by Edward Caswall, 1814-1878, alt. Music: Louis Lambillotte, SJ, 1796-1855; arr. © 2001, 2002, Universal Music Group- Brentwood Benson Music Publishing, Inc., and Kevin B. Hipp. All rights reserved. Used with permission of Music Services, Inc., o/b/o Universal Music Group-Brentwood Benson Music Publishing, Inc., and Spirit & Song, a divi- sion of OCP. All rights reserved. Matt Maher - Mass of Communion 2011 Thankyou Music (PRS) (adm. worldwide at EMICMGPublishing.com excluding Europe which is adm. by Kingswaysongs) / Valley Of Songs Music (BMI) / Worship Together Music (BMI) (adm. at EMICMGPublishing.com) / Ike Ndolo, published by spiritandsong.com, a division of OCP. 5536 NE Hassalo St. Portland, OR 97213. O Breathe on Me, O Breath of God. #81632. Type: Words and Music; First Line: O breathe on me, O Breath of God Text: CM; Edwin Hatch, 1835-1889, alt. Music: Trad. Irish melody. Contributors: ST. COLUMBA, Edwin Hatch Holy Spirit – Holy Spirit – Words and music by Bryan Torwalt and Katie Torwalt. -

35Oct11,2009.Pdf

50¢ October 11, 2009 Think Green Volume 83, No. 35 Recycle this paper Go Green todayscatholicnews.org Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend Go Digital ’’ Red Mass TTODAYODAY SS CCATHOLICATHOLIC Shaping legal minds Pages 13-14 In the spirit of St. Francis ... Healthcare reform Sisters of St. Francis of Perpetual Bishop D’Arcy makes statement Adoration look anew at Franciscan Page 3 spirituality and focus on the sacredness of creation LaGrange parish BY JUDY BRADFORD celebrates 75 years SOUTH BEND — About 100 pet owners, and their Eucharistic exhibition pets showed up for a special blessing on Sunday, Oct. 4, the day set aside as the feast of St. Francis of part of celebration Assisi, patron saint of animals and ecology. Page 8 The new event, sponsored by the Sisters of St. Francis of Perpetual Adoration, was part of a cele- bration to look anew at Franciscan spirituality, and focus on the sacredness of creation. “It also ties in to our mission to the poor because New saint we are to use only what we need in the way of water, food and goods, and not amass things just for the Father Damien canonized sake of amassing things,” said Sister Agnes Marie, an organizer for the event. this Sunday The public animal blessings took place in the Page 10 parking lot of Marian High School across the street from where the 120 sisters make their home, and JUDY BRADFORD also held a retreat on Saturday to study and reflect Mary Mac Donald receives the blessing from Franciscan Father Jim Kendzierski while hold- on the teachings of St.