Iloilo Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socio-Economics of Trawl Fisheries in Southeast Asia and Papua New Guinea

Socio-economics of trawl fisheries in Sout ISSN 2070-6103 50 FAO FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE PROCEEDINGS FAO FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE PROCEEDINGS 50 50 Socio-economics of trawl fisheries in Southeast Asia and Papua New Guinea Proceedings of the Regional Workshop on Trawl Fisheries Socio-economics 26-27 October 2015 Da Nang, Vietnam Socio-economics of trawl and Socio-economic Write-shop 25-26 April 2016 fisheries in Southeast Asia and Cha Am, Thailand Socio-economic surveys were carried out in pilot sites in Papua New Guinea (Gulf of Papua Prawn Fishery), Philippines (Samar Sea), Papua New Guinea Thailand (Trat and Chumphon) and Viet Nam (Kien Giang) under the project, Strategies for trawl fisheries bycatch management (REBYC-II CTI), funded by the Global Environment Facility and executed by FAO. In Indonesia, no study was conducted owing to the ban on trawl Proceedings of the Regional Workshop on Trawl Fisheries Socio-economics fisheries beginning January 2015. However, a paper based on key 26-27 October 2015 informant interviews was prepared. The socio-economic studies were Da Nang, Viet Nam undertaken to understand the contribution of trawl fisheries to food and security and livelihoods and determine the potential impacts of Socio-economic Write-shop management measures on stakeholder groups. Among the 25-26 April 2016 socio-economic information collected were the following: Cha Am, Thailand demographic structure of owners and crew; fishing practices – boat, gear, season, duration; catch composition, value chain and markets; contribution to livelihoods, food security and nutrition; role of women; heast Asia and Papua New Guinea costs and income from trawling; catch/income sharing arrangements; linkages with other sectors; and perceptions – resources, participation, compliance and the future. -

Crabbing Into an Uncertain Future: the Blue Swimming Crab Fisher in Coastal Town of Eastern Philippines

Crabbing into an uncertain future: the blue swimming crab fisher in coastal town of Eastern Philippines Item Type article Authors Cabrales, Pedro; Racuyal, Jesus; Mañoza, Alfredo Download date 26/09/2021 14:40:29 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/35879 THE COUNTRYSIDE DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH JOURNAL CRABBING INTO AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE: THE BLUE SWIMMING CRAB FISHER IN COASTAL TOWN, OF EASTERN PHILIPPINES Pedro S. Cabrales#1, Jesus T. Racuyal*2, Alfredo G. Mañoza*3 College of Arts and Sciences#, College of Fisheries and Marine Sciences*, Samar State University, Catbalogan City, Samar, Philippines [email protected] [email protected] 2 [email protected] Abstract This research project sought to find out the socio-economic status of the small- scale fishers of the blue swimming crab (Portunus pelagicus) in Samar, considering the diminishing volume of catch of the species in the recent years. Using a blend of quantitative and qualitative methods, the study employed an interview schedule, focus group discussion (FGD) and observation in collecting data not only from the fishers but also from other sectors directly involved in the blue swimming crab industry. Keywords: blue swimming crab, Samar fishery industry, socio-economic status, small scale fishers looked into its population, reproductive and I. INTRODUCTION fishery biology in Leyte and Samar. Later studies examined its appropriate food type, This study described the socio- prey density and stocking density in the larval economic status of the fishers of small-scale rearing in the Visayas area (Baylon, 2007), blue swimming crab (Portunus pelagicus) or and in Tamil Nadu, India (Josileen, 2011). Its ―karawasan‖ in Samar. -

Climate-Resilient Water Infrastructure Guidelines

No. 53 CLIMATE-RESILIENT WATER INFRASTRUCTURE: GUIDELINES AND LESSONS FROM THE USAID BE SECURE PROJECT March 17, 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency Climate-Resilient Water Infrastructure i for International Development. It was prepared by AECOM. CLIMATE-RESILIENT WATER INFRASTRUCTURE: GUIDELINES AND LESSONS FROM THE USAID BE SECURE PROJECT Submitted to: USAID Philippines Prepared by: AECOM International Development DISCLAIMER: The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Climate-Resilient Water Infrastructure ii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 1. LESSONS THAT AFFECT DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS ................................................................................ 2 2. CLIMATE IMPACTS ON WATER INFRASTRUCTURE .................................................................................... 4 3. SENSITIVITY OF MATERIALS USED IN WATER SUPPLY CONSTRUCTION: FINDINGS FROM POST-YOLANDA DAMAGE ASSESSMENTS ............................................................................................................ 9 4. STRATEGIC APPROACHES TO CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATON ....................................................... 10 5. CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION OPTIONS FOR WATER INFRASTRUCTURE FOR DIFFERENT CLIMATE DRIVERS ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Baybay Tall (BAYT) in the Philippines Rivera RL, Santos GA, Emmanuel EE, Rivera SM

Baybay Tall (BAYT) in the Philippines Rivera RL, Santos GA, Emmanuel EE, Rivera SM Conservation Baybay Tall (BAYT) is conserved at the Leyte State University (LSU) in Baybay, Leyte; Philippine Coconut Authority–Zamboanga Research Centre (PCA-ZRC) in San Ramon, Zamboanga City; and at the Coconut Breeding Trials Unit (CBTU) in Mambusao, Capiz in Panay Island, Philippines. History The Baybay Tall palms planted at the fi eld genebank at the PCA-ZRC were sourced from a plantation block of Tall palms in Baybay, Leyte in 1975. The original Tall palms, now known as BAYT were introduced to Baybay, Leyte from the Southern Tagalog Region in the mid 1950s. Identifi cation Baybay Tall variety is homogeneous and very leafy. It is characterized by high copra weight per nut, thin husk, bunches with short peduncles, fruits often trapped between the petioles of the leaves, and with very robust and thick stem. Its other known name is Laguna Tall (LAGT). The main characteristic of BAYT is its widened stem, forming a broad bulb at the base. The stem is the bigger recorded in the Coconut Genetic Resources Database, with 91 cm in diameter at 20 cm from the ground, so a circumference of 285 cm. In average, the Tall varieties recorded in the CGRD have a diameter of 53 cm at 20 cm from the ground level. Yield and production Baybay Tall is known for its relatively high meat weight and uniform stand. On the average, whole nut weight is 1464g; husk weight, 383g; shell weight, 245g and meat weight, 490g. BAYT palms yielded an average of 108 fruits per palm per year, 14 567 fruits per ha, 33.3 kg of copra per palm, and average copra of 4.5 tons per ha. -

Region 8 Households Under 4Ps Sorsogon Biri 950

Philippines: Region 8 Households under 4Ps Sorsogon Biri 950 Lavezares Laoang Palapag Allen 2174 Rosario San Jose 5259 2271 1519 811 1330 San Roque Pambujan Mapanas Victoria Capul 1459 1407 960 1029 Bobon Catarman 909 San Antonio Mondragon Catubig 1946 5978 630 2533 1828 Gamay San Isidro Northern Samar 2112 2308 Lapinig Lope de Vega Las Navas Silvino Lobos 2555 Jipapad 602 San Vicente 844 778 595 992 Arteche 1374 San Policarpo Matuguinao 1135 Calbayog City 853 Oras 11265 2594 Maslog Calbayog Gandara Dolores ! 2804 470 Tagapul-An Santa Margarita San Jose de Buan 2822 729 1934 724 Pagsanghan San Jorge Can-Avid 673 1350 1367 Almagro Tarangnan 788 Santo Nino 2224 1162 Motiong Paranas Taft 1252 2022 Catbalogan City Jiabong 1150 4822 1250 Sulat Maripipi Samar 876 283 San Julian Hinabangan 807 Kawayan San Sebastian 975 822 Culaba 660 659 Zumarraga Almeria Daram 1624 Eastern Samar 486 Biliran 3934 Calbiga Borongan City Naval Caibiran 1639 2790 1821 1056 Villareal Pinabacdao Biliran Cabucgayan Talalora 2454 1433 Calubian 588 951 746 2269 Santa Rita Maydolong 3070 784 Basey Balangkayan Babatngon 3858 617 1923 Leyte Llorente San Miguel Hernani Tabango 3158 Barugo 1411 1542 595 2404 1905 Tacloban City! General Macarthur Capoocan Tunga 7531 Carigara 1056 2476 367 2966 Alangalang Marabut Lawaan Balangiga Villaba 3668 Santa Fe Quinapondan 1508 1271 800 895 2718 Kananga Jaro 997 Salcedo 2987 2548 Palo 1299 Pastrana Giporlos Matag-Ob 2723 1511 902 1180 Leyte Tanauan Mercedes Ormoc City Dagami 2777 326 Palompon 6942 2184 Tolosa 1984 931 Julita Burauen 1091 -

5.3 Dungcaan River Basin 5.3.1 Basin Conditions (1) Natural Conditions 1

Main Report The Study on the Nationwide Flood Risk Assessment and the Flood Chapter 5 Mitigation Plan for the Selected Areas in the Republic of the Philippines 5.3 Dungcaan River Basin 5.3.1 Basin Conditions (1) Natural Conditions 1) Existing River System and Structures The Dungcaan River system is composed of three major rivers; Dungcaan River with a length of about 37.9 km (the principal drainage of this basin), the Pawonyan River with a length of 26.3 km (the right side main tributary), and the Tabayagon River with a length of 16.1km (the left side main tributary). The Dungcaan River Basin has the total area of 176 km2. The riverbed gradient of Dungcaan River, ranging from 1/40 to 1/240, is relatively gentle compared with that of the Pawonyan (1/14 to 1/130) and Tabayagon River (1/8 to 1/80). Dungcaan River flows through two channels in the downstream of the Baybay Bridge, the northern main stream and the southern sub-stream. The southern sub-stream was once closed with the concrete wall at the diversion point, and this concrete wall was broken in 2006. The existing river system of Dungcaan River is shown in Table 5.27 and Figure 5.10. Table 5.27 Rivers in the Dungcaan River Basin Catchment Area River Length (m) Remarks (km2) Dungcaan 176 37,900* * Excluding tributaries Pawonyan 52 26,300 Tributary Tabayagon 30 16,100 Tributary The major river structures relating to flood control are, as follows: • Concrete wall was constructed at the entrance of the southern sub-stream in the downstream of the Baybay Bridge. -

TACR: Philippines: Road Sector Improvement Project

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 41076-01 February 2011 Republic of the Philippines: Road Sector Improvement Project (Financed by the Japan Special Fund) Volume 1: Executive Summary Prepared by Katahira & Engineers International In association with Schema Konsult, Inc. and DCCD Engineering Corporation For the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, Lao PDR and This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Governments concerned, and ADB and the Governments cannot be held liable for its contents. All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY PORT AREA, MANILA ASSET PRESERVATION COMPONENT UNDER TRANCHE 1, PHASE I ROAD SECTOR INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND INVESTMENT PROGRAM (RSIDIP) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY in association KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS with SCHEMA KONSULT, DCCD ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL INC. CORPORATION Road Sector Institutional Development and Investment Program (RSIDIP): Executive Summary TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT ................................................... ES-1 2. OBJECTIVES OF THE PPTA............................................................ ES-1 3. SCOPE OF THE STUDY ................................................................. ES-2 4. SELECTION OF ROAD SECTIONS FOR DESIGN IN TRANCHE 1 ....... ES-3 5. PROJECT DESCRIPTION .............................................................. ES-8 -

Hydropower Potentials Estimation of Biliran Islands Based on Synthetic

Godinez and Salomon Science and Humanities Journal 13:83-98 (2019) DOI: https://doi.org/10.47773/shj.1998.121.1 Mendoza M. 2010. I Blog, You Buy: How Bloggers are creating a New Generation of Product Endorsers. Journal of Digital Research & Publishing, 7PM, 114-122. Hydropower Potentials Estimation of Biliran Islands Nilsson B. 2012. Politicians' blogs: Strategic self-presentations and identities. Based on Synthetic Aperture Radar Spatial Data Using Identity, 12(3), 247-265. Not Quite Nigella. 2009. Ten Things You Should Know about Food Bloggers. Soil and Water Assessment Tool Simulation Retrieved at www.notquitenigella.com/2009/07/13/10-things-you-should Arthur I. Tambong1*, Lemar N. Bacordo2, Kebin Ysrael F. Martinez3, Louie know-about-foodbloggers/ on May 26, 2017. Anthony Molato4 , Oliver Semblante5 , and Pastor P. Garcia6 Rettberg JW. 2008. Blogging (digital media and society). Robinson L. 2009. The art of food blogging. Retrieved at www.timesonline.co.uk/ tol/life_and_style/food_and_drink/real_food/article5 5358.eceon May 26, ABSTRACT 2017. Rutsaert P, Regan A, Pieniak Z, McConnon A, Moss A, Wall P, et al. 2013. The Use of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) spatial data simulation using Soil and Water Social Media in Food Risk and Benefit Communication. Trends in Food Science Assessment Tool (SWAT) was conducted to determine the hydropower generation & Technology, 30, 84-91. potentials of three (3) major islands of Biliran Province in the Philippines. Results Schneider EP, McGovern EE, Lynch CL & Brown LS. 2013. Do food blogs serve as a indicate that the dominant hydropower potentials of Biliran are of microhydro class source of nutritionally balanced recipes? An analysis of 6 popular food blogs. -

Legend Bernard Tomas Anahawan Matalom Oppus San Juan

Eastern Visayas: Road Conditions as of 7 December 2014 Sorsogon Biri Low-Lying Portions of the Road IMPASSABLE due to Flooding Lavezares Palapag San Jose Laoang Allen Rosario Catbalogan-Catarman via Allen Mondragon San PASSABLE Roque Mapanas Victoria Catarman Capul San Bobon Antonio Catubig Northern Samar Pambujan Gamay San Isidro Lapinig Lope de Vega Silvino Las Navas Lobos Jipapad Arteche Low-Lying Portions of the Road San Policarpo IMPASSABLE due to Flooding Calbayog City Matuguinao Oras Gandara Maslog Tagapul-An San Jose Dolores Catbalogan-LopeDeVega-Catarman Santa de Buan IMPASSABLE due to Margarita Landslide San Jorge Can-Avid Tacloban-Hinabangan-Taft Pagsanghan Jiabong-Tacloban Road Motiong PASSABLE Tarangnan Samar Almagro IMPASSABLESanto due to LandslideNino at Jiabong Masbate Paranas Taft Catbalogan Jiabong Taft-Borongan Road City IMPASSABLE due to Catbalogan-Jiabong Road Sulat Debris & Flooding Maripipi PASSABLE San Julian Hinabangan San Sebastian Kawayan Brgy.Buray-Taft RoadZumarraga Going In & Out of Almeria Culaba IMPASSABLE due to Calbiga Culaba, Biliran Biliran Debris & Flooding Eastern Samar INACCESSIBLE ACCESS ROADS Naval Daram Caibiran Pinabacdao Villareal Borongan City Biliran Calubian Talalora Cabucgayan Santa Rita San Maydolong Isidro Balangkayan Basey Babatngon Leyte San Llorente Tabango Hernani Barugo Miguel Tacloban City General Capoocan Tunga Balangiga Macarthur Carigara Marabut Alangalang Santa Villaba Lawaan Quinapondan Leyte Fe Tacloban to Borongan via Basey Kananga Jaro Salcedo Palo PASSABLE Giporlos All Roads -

2021–2029 Iloilo City Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) Volume 1 Preliminary Pages

2021–2029 Iloilo City Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) Volume 1 Preliminary Pages 3 City Planning and Development Office i 2021–2029 Iloilo City Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) Volume 1 Preliminary Pages Message from the Mayor Our beloved Iloilo City has progressively built on its glorious past to usher in a present, which is a source of pride and hope for our people, and an inspiring benchmark for our neighbors in Western Visayas, and beyond. Yet we are not a people who rest on our laurels. We aim higher. We move further. We scale greater heights. We level up. To level up Iloilo City, we begin with the end in mind. We need to envision a future where our city is livable, sustainable and resilient. We aim for a culturally vibrant and economically well-developed city where governance is a shared responsibility and where people are innovative and creative. We dream big, yet we stay realistic. We know that our collective journey as Ilonggos towards our envisioned future has to factor in developments in our external environment. Prudence likewise dictates that our resolve to level-up needs to consider our strengths and weaknesses as a local government unit and as a community. We need to assess our competencies and our resources, particularly our land and its current and future uses, so we are well-informed in determining the best development strategy to level up Iloilo City. I am, therefore, most pleased that we have already crafted the 2021-2029 Iloilo City Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP), which is a product of a series of consultations with various sectors. -

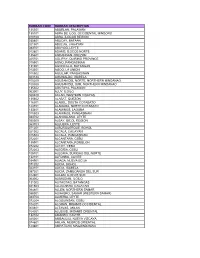

Rurban Code Rurban Description 135301 Aborlan

RURBAN CODE RURBAN DESCRIPTION 135301 ABORLAN, PALAWAN 135101 ABRA DE ILOG, OCCIDENTAL MINDORO 010100 ABRA, ILOCOS REGION 030801 ABUCAY, BATAAN 021501 ABULUG, CAGAYAN 083701 ABUYOG, LEYTE 012801 ADAMS, ILOCOS NORTE 135601 AGDANGAN, QUEZON 025701 AGLIPAY, QUIRINO PROVINCE 015501 AGNO, PANGASINAN 131001 AGONCILLO, BATANGAS 013301 AGOO, LA UNION 015502 AGUILAR, PANGASINAN 023124 AGUINALDO, ISABELA 100200 AGUSAN DEL NORTE, NORTHERN MINDANAO 100300 AGUSAN DEL SUR, NORTHERN MINDANAO 135302 AGUTAYA, PALAWAN 063001 AJUY, ILOILO 060400 AKLAN, WESTERN VISAYAS 135602 ALABAT, QUEZON 116301 ALABEL, SOUTH COTABATO 124701 ALAMADA, NORTH COTABATO 133401 ALAMINOS, LAGUNA 015503 ALAMINOS, PANGASINAN 083702 ALANGALANG, LEYTE 050500 ALBAY, BICOL REGION 083703 ALBUERA, LEYTE 071201 ALBURQUERQUE, BOHOL 021502 ALCALA, CAGAYAN 015504 ALCALA, PANGASINAN 072201 ALCANTARA, CEBU 135901 ALCANTARA, ROMBLON 072202 ALCOY, CEBU 072203 ALEGRIA, CEBU 106701 ALEGRIA, SURIGAO DEL NORTE 132101 ALFONSO, CAVITE 034901 ALIAGA, NUEVA ECIJA 071202 ALICIA, BOHOL 023101 ALICIA, ISABELA 097301 ALICIA, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR 012901 ALILEM, ILOCOS SUR 063002 ALIMODIAN, ILOILO 131002 ALITAGTAG, BATANGAS 021503 ALLACAPAN, CAGAYAN 084801 ALLEN, NORTHERN SAMAR 086001 ALMAGRO, SAMAR (WESTERN SAMAR) 083704 ALMERIA, LEYTE 072204 ALOGUINSAN, CEBU 104201 ALORAN, MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL 060401 ALTAVAS, AKLAN 104301 ALUBIJID, MISAMIS ORIENTAL 132102 AMADEO, CAVITE 025001 AMBAGUIO, NUEVA VIZCAYA 074601 AMLAN, NEGROS ORIENTAL 123801 AMPATUAN, MAGUINDANAO 021504 AMULUNG, CAGAYAN 086401 ANAHAWAN, SOUTHERN LEYTE -

2019 Regional Nutrition Situation

2020 Regional Nutrition Situation 2020 OPERATION TIMBANG PLUS COVERAGE Local Government No. of LGUs No. of LGU with % Submission Units Submission Province 6 6 100% City 7 7 100% Municipality 136 134 98.5% Note: No 2020 OPT+ report from Matag-ob and Villaba, Leyte Total Estimated population Actual number of Percent Coverage Population 0-59 months 0-59 4,742,337 533,039 349, 946 65.7% No. of IP PS measured 4,051 Number of Number of Total Number of Total Number of Province/Independent City Cities/Municipalities with Barangays with OPT Cities/Municipalities Barangays OPT Plus Results Results (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) EASTERN SAMAR 22 22 536 536 SAMAR 24 24 737 731 NORTHERN SAMAR 24 24 569 503 LEYTE 40 37 1,196 1,106 SOUTHERN LEYTE 18 18 430 430 BILIRAN 8 8 132 132 TACLOBAN 0 0 138 129 ORMOC 0 0 110 110 BAYBAY 0 0 92 90 MAASIN 0 0 70 70 CATBALOGAN 0 0 57 57 CALBAYOG 0 0 157 129 BORONGAN 0 0 61 46 STATUS (0-59 months Preschool Children) WEIGHT FOR AGE Magnitude Prevalence Underweight 20,882 6.0% Severely Underweight 5,240 1.5% UW + SUW 26, 122 7.5% HEIGHT FOR AGE Stunted 41,887 12.0% Severely Stunted 16,962 4.8% S+SS 57,980 16.8% WEIGHT FOR LENGTH/HEIGHT Normal 319, 210 91.2% Wasted 10, 136 2.9% Severely Wasted 3, 754 1.1% Overweight 9,625 2.8% Obese 7,137 2.0% W+SW 16,417 4% OW+Ob 15,896 4.8% 2020 REGIONAL NUTRITIONAL STATUS (per age group) 25.0% 20.0% 19.5% 19.2% 18.0% 17.6% 15.0% 11.3% 9.5% 9.2% 10.0% 8.8% 8.2% 6.8% 6.3% 5.3% 4.9% 5.0% 4.9% 4.4% 4.3% 4.3% 5.0% 3.6%3.9% 3.8% 3.3% 3.2% 2.5% 0.0% 0-5 439936-11 4418812-23 24-25 36-47 48-59 UW+SUW St+SSt