Odonata: Who They Are and What They Have Done for Us Lately: Classification and Ecosystem Services of Dragonflies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mosquito Survey Reveals the First Record of Aedes (Diptera: Culicidae) Species in Urban Area, Annaba District, Northeastern Algeria

Online ISSN: 2299-9884 Polish Journal of Entomology 90(1): 14–26 (2021) DOI: 10.5604/01.3001.0014.8065 Mosquito survey reveals the first record of Aedes (Diptera: Culicidae) species in urban area, Annaba district, Northeastern Algeria Djamel Eddine Rachid Arroussi1* , Ali Bouaziz2 , Hamid Boudjelida1 1 Laboratory of Applied Animal Biology, Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University Badji Mokhtar Annaba, Algeria. 2 Department of Biology, Faculty of Nature and Life Sciences, Mohamed Cherif Messaadia University Souk Ahras, Algeria. * Correspondending author: [email protected] Abstract: The diversity, distribution and ecology of mosquitoes, especially arbovirus vectors are important indices for arthropod-borne diseases control. The mosquito larvae were collected in different habitats in four sites of Annaba district, Algeria, during the period of March 2018 to February 2019 and the properties of larval habitats were recorded for each site. The systematic study revealed the presence of 8 species belonging to 4 genera; including Culex pipiens (Linnaeus, 1758), Culex modestus (Ficalbi, 1889), Culex theileri (Theobald, 1903), Culiseta longiareolata (Macquart, 1838), Anopheles labranchiae (Falleroni, 1926), Anopheles claviger (Meigen, 1804), Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus, 1762) and Aedes albopictus (Skuse, 1894). Among the species, C. pipiens presented the highest species abundance (RA %) (55.23%) followed by C. longiareolata (20.21%). The Aedes species are recorded for the first time in the study urban area. Variation of diversity in different sites depends on the type of breeding habitat. These results provided important information on species diversity, distribution and factors associated with breeding habitats. They could be used for the mosquito control and to prevent the spread of mosquito-borne diseases to the population of the region. -

Using Specimens from the Past to Understand the Living World Through Digitization

Using specimens from the past to understand the living world through digitization Drs. Jessica L. Ware, William Kuhn, Dirk Gassmann and John Abbott Rutgers University, Newark Dragonflies: Order Odonata Suborders Anisoptera (unequal wings): Dragonflies ~3000 species Anisozygoptera ~3 species Zygoptera: Damselflies ~3000 species Perchers, Fliers, Migrators, & Homebodies Dragonfly flight Wing venation affects wing camber, lift, and ultimately flight patterns Dragonfly flight Stiffness varies along length of the wing with vein density and thickness Dragonfly flight Certain wing traits are correlated with specific flight styles Dragonfly collections: invaluable treasures Collection name # spp. #specimens Florida State Collection 2728 150K Ware Lab Collection 373 4K Smithsonian Collection 253 200K M.L. May Collection 300 10K Dragonfly collections: invaluable treasures Harness information in collections Targeted Odonata Wing Digitization (TOWD) project TOWD project scanning protocol TOWD project scanning protocol TOWD project TOWD project TOWD project 10 10 TOWD project More information at: https://willkuhn.github.io/towd/ Aspect ratios: How elongate is the wing compared to its overall area? • High Aspect ratio Low Aspect ratio Long narrow wings, Wing Short broad wings, optimized for: Wing optimized long-distance flight for: Maneuverability, turning High Aspect Low Aspect Ratio Ratio More data on aspect ratios, better interpretations? 2007: Hand measured forewings of 85 specimens, 7 months work More data on apsect ratios, better interpretations? 2007: Hand measured forewings of 85 specimens, 7 months 2019: Odomatic measurements for 206 work specimens, 2-3 minutes of work! Are there differences in aspect ratios? Perchers have significantly lower aspect ratios than fliers. The p-value is .001819. The result is significant at p < .05. -

![[The Pond\. Odonatoptera (Odonata)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4965/the-pond-odonatoptera-odonata-114965.webp)

[The Pond\. Odonatoptera (Odonata)]

Odonatological Abstracts 1987 1993 (15761) SAIKI, M.K. &T.P. LOWE, 1987. Selenium (15763) ARNOLD, A., 1993. Die Libellen (Odonata) in aquatic organisms from subsurface agricultur- der “Papitzer Lehmlachen” im NSG Luppeaue bei al drainagewater, San JoaquinValley, California. Leipzig. Verbff. NaturkMus. Leipzig 11; 27-34. - Archs emir. Contam. Toxicol. 16: 657-670. — (US (Zur schonen Aussicht 25, D-04435 Schkeuditz). Fish & Wildl. Serv., Natn. Fisheries Contaminant The locality is situated 10km NW of the city centre Res. Cent., Field Res, Stn, 6924 Tremont Rd, Dixon, of Leipzig, E Germany (alt, 97 m). An annotated CA 95620, USA). list is presented of 30 spp., evidenced during 1985- Concentrations of total selenium were investigated -1993. in plant and animal samplesfrom Kesterson Reser- voir, receiving agricultural drainage water (Merced (15764) BEKUZIN, A.A., 1993. Otryad Strekozy - — Co.) and, as a reference, from the Volta Wildlife Odonatoptera(Odonata). [OrderDragonflies — km of which Area, ca 10 S Kesterson, has high qual- Odonatoptera(Odonata)].Insectsof Uzbekistan , pp. ity irrigationwater. Overall,selenium concentrations 19-22,Fan, Tashkent, (Russ.). - (Author’s address in samples from Kesterson averaged about 100-fold unknown). than those from Volta. in and A rather 20 of higher Thus, May general text, mentioning (out 76) spp. Aug. 1983, the concentrations (pg/g dry weight) at No locality data, but some notes on their habitats Kesterson in larval had of 160- and vertical in Central Asia. Zygoptera a range occurrence 220 and in Anisoptera 50-160. In Volta,these values were 1.2-2.I and 1.1-2.5, respectively. In compari- (15765) GAO, Zhaoning, 1993. -

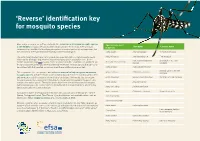

Identification Key for Mosquito Species

‘Reverse’ identification key for mosquito species More and more people are getting involved in the surveillance of invasive mosquito species Species name used Synonyms Common name in the EU/EEA, not just professionals with formal training in entomology. There are many in the key taxonomic keys available for identifying mosquitoes of medical and veterinary importance, but they are almost all designed for professionally trained entomologists. Aedes aegypti Stegomyia aegypti Yellow fever mosquito The current identification key aims to provide non-specialists with a simple mosquito recog- Aedes albopictus Stegomyia albopicta Tiger mosquito nition tool for distinguishing between invasive mosquito species and native ones. On the Hulecoeteomyia japonica Asian bush or rock pool Aedes japonicus japonicus ‘female’ illustration page (p. 4) you can select the species that best resembles the specimen. On japonica mosquito the species-specific pages you will find additional information on those species that can easily be confused with that selected, so you can check these additional pages as well. Aedes koreicus Hulecoeteomyia koreica American Eastern tree hole Aedes triseriatus Ochlerotatus triseriatus This key provides the non-specialist with reference material to help recognise an invasive mosquito mosquito species and gives details on the morphology (in the species-specific pages) to help with verification and the compiling of a final list of candidates. The key displays six invasive Aedes atropalpus Georgecraigius atropalpus American rock pool mosquito mosquito species that are present in the EU/EEA or have been intercepted in the past. It also contains nine native species. The native species have been selected based on their morpho- Aedes cretinus Stegomyia cretina logical similarity with the invasive species, the likelihood of encountering them, whether they Aedes geniculatus Dahliana geniculata bite humans and how common they are. -

![Odonata: Zygoptera] Pessacq, Pablo Doctor En Ciencias Naturales](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9577/odonata-zygoptera-pessacq-pablo-doctor-en-ciencias-naturales-249577.webp)

Odonata: Zygoptera] Pessacq, Pablo Doctor En Ciencias Naturales

Naturalis Repositorio Institucional Universidad Nacional de La Plata http://naturalis.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo Sistemática filogenética y biogeografía de los representantes neotropicales de la familia Protoneuridae [Odonata: Zygoptera] Pessacq, Pablo Doctor en Ciencias Naturales Dirección: Muzón, Javier Co-dirección: Spinelli, Gustavo Ricardo Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo 2005 Acceso en: http://naturalis.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar/id/20120126000079 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) SISTEMÁTICA FILOGENÉTICA Y BIOGEOGRAFÍA DE LOS REPRESENTANTES NEOTROPICALES DE LA FAMILIA PROTONEURIDAE (ODONATA: ZYGOPTERA). Autor: LIC. PABLO PESSACQ Director: DR. JAVIER MUZÓN Codirector: DR. GUSTAVO R. SPINELLI UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE LA PLATA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS NATURALES Y MUSEO 2005 Agradecimientos Todo mi gratitud a mis directores de tesis, Dr. Javier Muzón y Dr. Gustavo Spinelli, quienes me iniciaron pacientemente en el camino de la Sistemática y de la Entomología. Al Dr. Rosser Garrison, su ayuda desinteresada contribuyó mucho en el avance de esta tesis. Al Dr. Oliver Flint, siempre dispuesto a enviar preciados ejemplares. Al la Dra. Janira Martins Costa, el Dr. Juerg De Marmels y el Dr. Frederic Lencioni, por la ayuda prestada y buena predisposición. A Javier, por la amistad, los mates y los viajes compartidos. A mis compañeros de ILPLA: Analía, Eugenia, Juliana, Lia, Lucila (en especial por su habilidad en la repostería), Soledad, Federico, Leandro y Sergio. Hacen que el trabajo y los viajes sean más placenteros todavía. A mi tío, Carlos Grisolía, quien incentivó en mi desde muy chico el interés por los artrópodos. -

Dragonflies and Damselflies in Your Garden

Natural England works for people, places and nature to conserve and enhance biodiversity, landscapes and wildlife in rural, urban, coastal and marine areas. Dragonflies and www.naturalengland.org.uk © Natural England 2007 damselflies in your garden ISBN 978-1-84754-015-7 Catalogue code NE21 Written by Caroline Daguet Designed by RR Donnelley Front cover photograph: A male southern hawker dragonfly. This species is the one most commonly seen in gardens. Steve Cham. www.naturalengland.org.uk Dragonflies and damselflies in your garden Dragonflies and damselflies are Modern dragonflies are tiny by amazing insects. They have a long comparison, but are still large and history and modern species are almost spectacular enough to capture the identical to ancestors that flew over attention of anyone walking along a prehistoric forests some 300 million river bank or enjoying a sunny years ago. Some of these ancient afternoon by the garden pond. dragonflies were giants, with This booklet will tell you about the wingspans of up to 70 cm. biology and life-cycles of dragonflies and damselflies, help you to identify some common species, and tell you how you can encourage these insects to visit your garden. Male common blue damselfly. Most damselflies hold their wings against their bodies when at rest. BDS Dragonflies and damselflies belong to Dragonflies the insect order known as Odonata, Dragonflies are usually larger than meaning ‘toothed jaws’. They are often damselflies. They are stronger fliers and referred to collectively as ‘dragonflies’, can often be found well away from but dragonflies and damselflies are two water. When at rest, they hold their distinct groups. -

Development of Encyclopedia Boyong Sleman Insekta River As Alternative Learning Resources

PROC. INTERNAT. CONF. SCI. ENGIN. ISSN 2597-5250 Volume 3, April 2020 | Pages: 629-634 E-ISSN 2598-232X Development of Encyclopedia Boyong Sleman Insekta River as Alternative Learning Resources Rini Dita Fitriani*, Sulistiyawati Biological Education Faculty of Science and Technology, UIN Sunan Kalijaga Jl. Marsda Adisucipto Yogyakarta, Indonesia Email*: [email protected] Abstract. This study aims to determine the types of insects Coleoptera, Hemiptera, Odonata, Orthoptera and Lepidoptera in the Boyong River, Sleman Regency, Yogyakarta, to develop the Encyclopedia of the Boyong River Insect and to determine the quality of the encyclopedia developed. The method used in the research inventory of the types of insects Coleoptera, Hemiptera, Odonata, Orthoptera and Lepidoptera insects in the Boyong River survey method with the results of the study found 46 species of insects consisting of 2 Coleoptera Orders, 2 Hemiptera Orders, 18 orders of Lepidoptera in Boyong River survey method with the results of the research found 46 species of insects consisting of 2 Coleoptera Orders, 2 Hemiptera Orders, 18 orders of Lepidoptera in Boyong River survey method. odonata, 4 Orthopterous Orders and 20 Lepidopterous Orders from 15 families. The encyclopedia that was developed was created using the Adobe Indesig application which was developed in printed form. Testing the quality of the encyclopedia uses a checklist questionnaire and the results of the percentage of ideals from material experts are 91.1% with very good categories, 91.7% of media experts with very good categories, peer reviewers 92.27% with very good categories, biology teachers 88, 53% with a very good category and students 89.8% with a very good category. -

The Superfamily Calopterygoidea in South China: Taxonomy and Distribution. Progress Report for 2009 Surveys Zhang Haomiao* *PH D

International Dragonfly Fund - Report 26 (2010): 1-36 1 The Superfamily Calopterygoidea in South China: taxonomy and distribution. Progress Report for 2009 surveys Zhang Haomiao* *PH D student at the Department of Entomology, College of Natural Resources and Environment, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China. Email: [email protected] Introduction Three families in the superfamily Calopterygoidea occur in China, viz. the Calo- pterygidae, Chlorocyphidae and Euphaeidae. They include numerous species that are distributed widely across South China, mainly in streams and upland running waters at moderate altitudes. To date, our knowledge of Chinese spe- cies has remained inadequate: the taxonomy of some genera is unresolved and no attempt has been made to map the distribution of the various species and genera. This project is therefore aimed at providing taxonomic (including on larval morphology), biological, and distributional information on the super- family in South China. In 2009, two series of surveys were conducted to Southwest China-Guizhou and Yunnan Provinces. The two provinces are characterized by karst limestone arranged in steep hills and intermontane basins. The climate is warm and the weather is frequently cloudy and rainy all year. This area is usually regarded as one of biodiversity “hotspot” in China (Xu & Wilkes, 2004). Many interesting species are recorded, the checklist and photos of these sur- veys are reported here. And the progress of the research on the superfamily Calopterygoidea is appended. Methods Odonata were recorded by the specimens collected and identified from pho- tographs. The working team includes only four people, the surveys to South- west China were completed by the author and the photographer, Mr. -

André Nel Sixtieth Anniversary Festschrift

Palaeoentomology 002 (6): 534–555 ISSN 2624-2826 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pe/ PALAEOENTOMOLOGY PE Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press Editorial ISSN 2624-2834 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.2.6.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:25D35BD3-0C86-4BD6-B350-C98CA499A9B4 André Nel sixtieth anniversary Festschrift DANY AZAR1, 2, ROMAIN GARROUSTE3 & ANTONIO ARILLO4 1Lebanese University, Faculty of Sciences II, Department of Natural Sciences, P.O. Box: 26110217, Fanar, Matn, Lebanon. Email: [email protected] 2State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China. 3Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité, ISYEB-UMR 7205-CNRS, MNHN, UPMC, EPHE, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Sorbonne Universités, 57 rue Cuvier, CP 50, Entomologie, F-75005, Paris, France. 4Departamento de Biodiversidad, Ecología y Evolución, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain. FIGURE 1. Portrait of André Nel. During the last “International Congress on Fossil Insects, mainly by our esteemed Russian colleagues, and where Arthropods and Amber” held this year in the Dominican several of our members in the IPS contributed in edited volumes honoring some of our great scientists. Republic, we unanimously agreed—in the International This issue is a Festschrift to celebrate the 60th Palaeoentomological Society (IPS)—to honor our great birthday of Professor André Nel (from the ‘Muséum colleagues who have given us and the science (and still) national d’Histoire naturelle’, Paris) and constitutes significant knowledge on the evolution of fossil insects a tribute to him for his great ongoing, prolific and his and terrestrial arthropods over the years. -

Megalagrion Nigrohamatum Nigrolineatum (Perkins 1899) Blackline Hawaiian Damselfly Odonata: Zygoptera: Coenagrionidae

Megalagrion nigrohamatum nigrolineatum (Perkins 1899) Blackline Hawaiian damselfly Odonata: Zygoptera: Coenagrionidae Photo credit Hawaii Biological Survey Profile prepared by Celeste Mazzacano, The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation SUMMARY Megalagrion nigrohamatum nigrolineatum is endemic to the Hawaiian island of Oahu. This subspecies was found historically in the mountain ranges of Koolau and Waianae, and is currently known from 16 stream sites at high altitudes in the Koolau Range. Its limited habitat and small scattered populations may affect long-term stability. The species is susceptible to the effects of habitat loss and introduced species. Research should focus on habitat management and protection, and control of invasive species. CONSERVATION STATUS Rankings: Canada – Species at Risk Act: N/A Canada – provincial status: N/A Mexico: N/A USA – Endangered Species Act: Candidate USA – state status: S2 Imperiled NatureServe: G4T2 Apparently secure; Subspecies imperiled IUCN Red List: VU Vulnerable SPECIES PROFILE DESCRIPTION Megalagrion n. nigrolineatum is in the family Coenagrionidae (pond damsels). Adults are medium-sized, from 35-45 mm (1.4-1.8 in.) in length with a wingspan of 43-50 mm (1.7-2.0 in.). Adults of both sexes can be recognized by the lime green to blue-green coloration on the lower Species Profile: Megalagrion nigrohamatum nigrolineatum 1 half of the face and eyes (Polhemus & Asquith 1996), and the top portion of the eyes is bright red. Males have a dark abdomen with an orange-red tip, and a broad yellow, red, or orange patch on the side of the thorax. Females have a similar pattern but the patch on the thorax may be yellow to light blue, and final segment of the abdomen is dull orange. -

Draft Index of Keys

Draft Index of Keys This document will be an update of the taxonomic references contained within Hawking 20001 which can still be purchased from MDFRC on (02) 6024 9650 or [email protected]. We have made the descision to make this draft version publicly available so that other taxonomy end-users may have access to the information during the refining process and also to encourage comment on the usability of the keys referred to or provide information on other keys that have not been reffered to. Please email all comments to [email protected]. 1Hawking, J.H. (2000) A preliminary guide to keys and zoological information to identify invertebrates form Australian freshwaters. Identification Guide No. 2 (2nd Edition), Cooperative Research Centre for Freshwater Ecology: Albury Index of Keys Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Major Group ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Minor Group ................................................................................................................................................... 8 Order ............................................................................................................................................................. -

Adhesion Performance in the Eggs of the Philippine Leaf Insect Phyllium Philippinicum (Phasmatodea: Phylliidae)

insects Article Adhesion Performance in the Eggs of the Philippine Leaf Insect Phyllium philippinicum (Phasmatodea: Phylliidae) Thies H. Büscher * , Elise Quigley and Stanislav N. Gorb Department of Functional Morphology and Biomechanics, Institute of Zoology, Kiel University, Am Botanischen Garten 9, 24118 Kiel, Germany; [email protected] (E.Q.); [email protected] (S.N.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 June 2020; Accepted: 25 June 2020; Published: 28 June 2020 Abstract: Leaf insects (Phasmatodea: Phylliidae) exhibit perfect crypsis imitating leaves. Although the special appearance of the eggs of the species Phyllium philippinicum, which imitate plant seeds, has received attention in different taxonomic studies, the attachment capability of the eggs remains rather anecdotical. Weherein elucidate the specialized attachment mechanism of the eggs of this species and provide the first experimental approach to systematically characterize the functional properties of their adhesion by using different microscopy techniques and attachment force measurements on substrates with differing degrees of roughness and surface chemistry, as well as repetitive attachment/detachment cycles while under the influence of water contact. We found that a combination of folded exochorionic structures (pinnae) and a film of adhesive secretion contribute to attachment, which both respond to water. Adhesion is initiated by the glue, which becomes fluid through hydration, enabling adaption to the surface profile. Hierarchically structured pinnae support the spreading of the glue and reinforcement of the film. This combination aids the egg’s surface in adapting to the surface roughness, yet the attachment strength is additionally influenced by the egg’s surface chemistry, favoring hydrophilic substrates.