Aspects of Herbie Hancock's Pre-Electric Improvisational

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": an Analytical Approach to Jazz

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": An Analytical Approach to Jazz Styles and Influences Nicholas Vincent DiSalvio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation DiSalvio, Nicholas Vincent, "Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": An Analytical Approach to Jazz Styles and Influences" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. CHARLES RUGGIERO’S “TENOR ATTITUDES”: AN ANALYTICAL APPROACH TO JAZZ STYLES AND INFLUENCES A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Nicholas Vincent DiSalvio B.M., Rowan University, 2009 M.M., Illinois State University, 2013 May 2016 For my wife Pagean: without you, I could not be where I am today. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my committee for their patience, wisdom, and guidance throughout the writing and revising of this document. I extend my heartfelt thanks to Dr. Griffin Campbell and Dr. Willis Delony for their tireless work with and belief in me over the past three years, as well as past professors Dr. -

Dexter Gordon Doin' All Right + a Swingin' Affair Mp3, Flac, Wma

Dexter Gordon Doin' All Right + A Swingin' Affair mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Doin' All Right + A Swingin' Affair Country: Europe Released: 2013 Style: Hard Bop, Post Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1122 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1983 mb WMA version RAR size: 1754 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 382 Other Formats: MPC VOX ASF MMF FLAC DTS MP2 Tracklist Doin' Allright 1-1 I Was Doing All Right 1-2 You've Changed 1-3 For Regulars Only 1-4 Society Red 1-5 It's You Or No One 1-6 I Want More 1-7 For Regulars Only (alt Take) A Swingin' Affair 2-1 Soy Califa 2-2 Don't Explain 2-3 You Stepped Out Of A Dream 2-4 Tha Backbone 2-5 (It Will Have To Do) Until The Real Thing Comes Along 2-6 McSplivens Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Universal International Music B.V. Copyright (c) – Universal International Music B.V. Credits Producer – Alfred Lion (tracks: 1-1 to 1-7, 2-1 to 2-6) Reissue Producer – Michael Cuscuna (tracks: 1-1 to 1-7, 2-1 to 2-6) Remastered By – Rudy Van Gelder (tracks: 1-1 to 1-7, 2-1 to 2-6) Notes ©+℗ 2013 Universal International Music B.V. ALBUM 1: Doin' Allright - Label code: 00724359650425 - Original Album Label: Blue Note 96503 - Recorded on May 6, 1961 by Rudy Van Gelder - Tracks 1-6, 1-7 not part of original LP - Remastered in 2003 by Rudy Van Gelder - ©+℗ 2004 Blue Note Records ALBUM 2: Swingin' Affair - Label code: 00077778413325 - Original Album Label: Blue Note 84133 - Remasterd in 2005 by Rudy Van Gelder - ©+℗ 2006 Blue Note Records Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0600753471142 Rights Society: BIEM/SDRM Label Code: LC 01846 Matrix / Runout (CD1): 07243 596 504-2 01 + 53412723 Mastering SID Code (CD1): IFPI LV27 Mould SID Code (CD1): IFPI 0139 Matrix / Runout (CD2): 00777 784 133-2 01 * 53412693 Mastering SID Code (CD2): IFPI LV26 Mould SID Code (CD2): IFPI 0120 Related Music albums to Doin' All Right + A Swingin' Affair by Dexter Gordon 1. -

Bebopnet: Deep Neural Models for Personalized Jazz Improvisations - Supplementary Material

BEBOPNET: DEEP NEURAL MODELS FOR PERSONALIZED JAZZ IMPROVISATIONS - SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 1. SUPPLEMENTARY MUSIC SAMPLES We provide a variety of MP3 files of generated solos in: https://shunithaviv.github.io/bebopnet Each sample starts with the melody of the jazz stan- dard, followed by an improvisation whose duration is one chorus. Sections BebopNet in sample and BebopNet out of sample contain solos of Bebop- Net without beam search over chord progressions in and out of the imitation training set, respectively. Section Diversity contains multiple solos over the same stan- Figure 1. Digital CRDI controlled by a user to provide dard to demonstrate the diversity of the model for user- continuous preference feedback. 4. Section Personalized Improvisations con- tain solos following the entire personalization pipeline for the four different users. Section Harmony Guided Improvisations contain solos generated with a har- monic coherence score instead of the user preference score, as described in Section 3.2. Section Pop songs contains solos over the popular non-jazz song. Some of our favorite improvisations by BebopNet are presented in the first sec- Algorithm 1: Score-based beam search tion, Our Favorite Jazz Improvisations. Input: jazz model fθ; score model gφ; batch size b; beam size k; update interval δ; input in τ sequence Xτ = x1··· xτ 2 X 2. METHODS τ+T Output: sequence Xτ+T = x1··· xτ+T 2 X in in in τ×b 2.1 Dataset Details Vb = [Xτ ;Xτ ; :::; Xτ ] 2 X ; | {z } A list of the solos included in our dataset is included in b times scores = [−1; −1; :::; −1] 2 Rb section 4. -

JELLY ROLL MORTON's

1 The TENORSAX of WARDELL GRAY Solographers: Jan Evensmo & James Accardi Last update: June 8, 2014 2 Born: Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Feb. 13, 1921 Died: Las Vegas, Nevada, May 25, 1955 Introduction: Wardell Gray was the natural candidate to transfer Lester Young’s tenorsax playing to the bebop era. His elegant artistry lasted only a few years, but he was one of the greatest! History: First musical studies on clarinet in Detroit where he attended Cass Tech. First engagements with Jimmy Raschel and Benny Carew. Joined Earl Hines in 1943 and stayed over two years with the band before settling on the West Coast. Came into prominence through his performances and recordings with the concert promoter Gene Norman and his playing in jam sessions with Dexter Gordon.; his famous recording with Gordon, “The Chase” (1947), resulted from these sessions as did an opportunity to record with Charlie Parker (1947). As a member of Benny Goodman’s small group WG was an important figure in Goodman’s first experiments with bop (1948). He moved to New York with Goodman and in 1948 worked at the Royal Roost, first with Count Basie, then with the resident band led by Tadd Dameron; he made recordings with both leaders. After playing with Goodman’s bigband (1948-49) and recording in Basie’s small group (1950-51), WG returned to freelance work on the West Coast and Las Vegas. He took part in many recorded jam sessions and also recorded with Louie Bellson in 1952-53). The circumstances around his untimely death (1955) is unclear (ref. -

John Bailey Randy Brecker Paquito D'rivera Lezlie Harrison

192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:36 AM Page 1 E Festival & Outdoor THE LATIN SIDE 42 Concert Guide OF HOT HOUSE P42 pages 30-41 June 2018 www.hothousejazz.com Smoke Jazz & Supper Club Page 17 Blue Note Page 19 Lezlie Harrison Paquito D'Rivera Randy Brecker John Bailey Jazz Forum Page 10 Smalls Jazz Club Page 10 Where To Go & Who To See Since 1982 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:36 AM Page 2 2 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 3 3 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 4 4 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 5 5 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 6 6 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 7 7 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 8 8 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 11:45 AM Page 9 9 192496_HH_June_0 5/25/18 10:37 AM Page 10 WINNING SPINS By George Kanzler RUMPET PLAYERS ARE BASI- outing on soprano sax. cally extroverts, confident and proud Live 1988, Randy Brecker Quintet withT a sound and tone to match. That's (MVDvisual, DVD & CD), features the true of the two trumpeters whose albums reissue of a long out-of-print album as a comprise this Winning Spins: John Bailey CD, accompanying a previously unreleased and Randy Brecker. Both are veterans of DVD of the live date, at Greenwich the jazz scene, but with very different Village's Sweet Basil, one of New York's career arcs. John has toiled as a first-call most prominent jazz clubs in the 1980s trumpeter for big bands and recording ses- and 1990s. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

June 25, 2018 Jazz Album Chart

Jazz Album Chart June 25, 2018 TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW Move Weeks Reports Adds Joey Alexander 1 1 1 1 Eclipse Motema 302 285 17 7 49 2 6 weeks at No. 1 Kenny Barron Quintet 2 2 3 2 Concentric Circles Blue Note 287 257 30 7 58 5 Most Reports 3 3 2 2 Eddie Henderson Be Cool Smoke Sessions 272 246 26 7 55 1 4 4 4 2 Don Braden Earth, Wind and Wonder Creative Perspective Music 254 242 12 8 53 2 5 5 7 5 Jim Snidero & Jeremy Pelt Jubilation! Savant 242 232 10 8 53 0 6 6 5 4 Allan Harris The Genius of Eddie Jefferson Resilience 231 221 10 6 54 4 6 7 8 6 Tia Fuller Diamond Cut Mack Avenue 231 217 14 6 48 3 8 13 22 8 Manhattan Transfer The Junction BMG 211 178 33 8 40 2 9 13 11 9 Mike LeDonne and The Groover Quartet From The Heart Savant 210 178 32 4 55 6 10 23 25 10 Freddy Cole My Mood Is You HighNote 193 155 38 4 51 5 10 10 10 10 Ellis Marsalis The Ellis Marsalis Quintet Plays the Music of ELM 193 196 -3 5 45 2 Ellis Marsalis 12 9 13 7 Van Morrison and Joey DeFrancesco You’re Driving Me Crazy Sony / Legacy 192 201 -9 8 38 2 13 16 15 13 McClenty Hunter, Jr. The Groove Hunter Strikezone 191 171 20 5 48 2 14 8 16 8 Benito Gonzalez, Gerry Gibbs & Essiet Essiet Passion, Reverence, Transcendence Whaling City Sound 183 202 -19 7 41 2 15 12 6 1 Kurt Elling The Questions OKeh 182 189 -7 13 37 0 16 16 20 16 Brubeck Brothers Timeline Blue Forest 178 171 7 9 44 3 17 11 9 7 Bill O’Connell Jazz Latin Savant 175 191 -16 7 42 0 18 15 11 2 Renee Rosnes Beloved Of The Sky Smoke Sessions 173 177 -4 11 40 1 19 18 21 2 Wynton Marsalis Septet United -

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

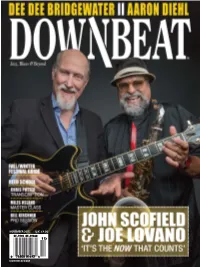

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; -

Gazette Volume 21, No

GAZETTE Volume 21, No. 15 • April 23, 2010 • A weekly publication for Library staff Library Celebrates the A Whole Lot Dexter Gordon Acquisition Of Tweeting Going On Twitter is donating its digital archive of public tweets to the Library of Congress. Twitter is a leading social-networking service that enables users to send and receive tweets, which consist of web messages of up to 140 characters. Twitter processes more than 50 mil- lion tweets per day from people around the world. The Library will receive all public tweets – which number in the billions – from the 2006 inception of the service to the present. “The Twitter digital archive has extraordinary potential for research into Abby Brack our contemporary way of life,” said Librar- Maxine Gordon discusses the making of the 1986 film, “‘Round Midnight,” a film that ian of Congress James H. Billington. “This starred her late husband, Dexter Gordon, in a role that earned him an Oscar nomination. information provides detailed evidence career. Consisting primarily of sound about how technology-based social net- By Sheryl Cannady recordings, the collection also includes works form and evolve over time. The egendary jazz musician Dexter interviews and items from Gordon’s film collection also documents a remarkable Gordon (1923–1990) is considered and television appearances. range of social trends. Anyone who wants Lone of the world’s greatest tenor The melodic sounds of the legend- to understand how an ever-broadening saxophonists and one of the first musi- ary saxophonist filled the theater as public is using social media to engage cians to adapt the sounds of bebop to the enthusiastic crowd took their seats, in an ongoing debate regarding social the tenor saxophone. -

Readers Poll

84 READERS POLL DOWNBEAT HALL OF FAME One night in November 1955, a cooperative then known as The Jazz Messengers took the stage of New York’s Cafe Bohemia. Their performance would yield two albums (At The Cafe Bohemia, Volume 1 and Volume 2 on Blue Note) and help spark the rise of hard-bop. By Aaron Cohen t 25 years old, tenor saxophonist Hank Mobley should offer a crucial statement on how jazz was transformed during Aalready have been widely acclaimed for what he that decade. Dissonance, electronic experimentation and more brought to the ensemble: making tricky tempo chang- open-ended collective improvisation were not the only stylis- es sound easy, playing with a big, full sound on ballads and pen- tic advances that marked what became known as “The ’60s.” ning strong compositions. But when his name was introduced Mobley’s warm tone didn’t necessarily coincide with clichés on the first night at Cafe Bohemia, he received just a brief smat- of the tumultuous era, as the saxophonist purposefully placed tering of applause. That contrast between his incredible artistry himself beyond perceived trends. and an audience’s understated reaction encapsulates his career. That individualism came across in one of his rare inter- Critic Leonard Feather described Mobley as “the middle- views, which he gave to writer John Litweiler for “Hank Mobley: weight champion of the tenor saxophone.” Likely not intended The Integrity of the Artist–The Soul of the Man,” which ran in to be disrespectful, the phrase implied that his sound was some- the March 29, 1973, issue of DownBeat. -

The Bob Devos Organ Quartet

The Bob DeVos Organ Quartet Bob DeVos Guitar Ralph Bowen Tenor Saxophone Dan Kostelnik Hammond B-3 Organ Steve Johns Drums “I play, compose and arrange to explore a new potential of the Hammond B3 organ genre without losing the tradition, the spirit and—at—heart—the blues feeling of the great organ groups I came up through the ranks with.” – Bob DeVos The Bob DeVos Organ Group has been performing to enthusiastic, full houses and great acclaim since 2005. It unites Bob with two terrific musicians: Hammond B3 organist Dan Kostelnik and drummer Steve Johns frequently joined by tenor great Ralph Bowen. With long, blues-drenched melodic lines and a distinctive, horn-like sound, guitarist-composer Bob DeVos is hailed as “a master with a sound to die for: rich, full, deep, positive, round and warm.“ Bob cut his teeth in jazz as the replacement for Pat Martino in the Trudy Pitts & Mr. C. Trio, then went on to perform and record extensively with other Hammond B-3 Organ group legends: Charles Earland, Jimmy McGriff-Hank Crawford, Richard “Groove” Holmes-Sonny Stitt, Jack McDuff and modern organists Joey DeFrancesco, Dr. Lonnie Smith, and Mike LeDonne, as well as many, many jazz greats past and current outside the organ jazz genre. Dan Kostelnik brings a mastery over the traditional organ idiom combined with the ability to handle modern, harmonically complex structures. An in-demand player, Dan is a Down Beat Rising Star. Like Bob, Steve Johns is a complete musician—dynamic and musical with extensive experience playing and recording in a wide range of styles. -

Blue Note: Still the Finest in Jazz Since 1939 Published on December 30, 2018 by Richard Havers

Blue Note: Still The Finest In Jazz Since 1939 Published on December 30, 2018 By Richard Havers Founded in 1939 by Alfred Lion, Blue Note is loved, respected and revered as one of the most important record labels in the history of music. Blue Note is loved, revered, respected and recognized as one of the most important record labels in the history of popular music. Founded in 1939 by Alfred Lion, who had only arrived in America a few years earlier having fled the oppressive Nazi regime in his native Germany, Blue Note has continually blazed a trail of innovation in both music and design. Its catalogue of great albums, long-playing records and even 78rpm and 45rpm records is for many the holy grail of jazz. Blue Note is loved, revered, respected and recognized as one of the most important record labels in the history of popular music. Founded in 1939 by Alfred Lion, who had only arrived in America a few years earlier having fled the oppressive Nazi regime in his native Germany, Blue Note has continually blazed a trail of innovation in both music and design. Its catalogue of great albums, long-playing records and even 78rpm and 45rpm records is for many the holy grail of jazz. It all began when Alfred Lion went to the ‘Spirituals to Swing’ concert at New York’s Carnegie Hall a few days before Christmas 1938. A week or so later he went to Café Society, a newly opened club, to talk to Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis, who had seen them play at Carnegie Hall.