Qualified Immunity: a View from the Bench

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT EASTERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK ------X : in Re: : Chapter 11 : RUBIE’S COSTUME COMPANY, INC., Et Al

Case 8-20-71970-ast Doc 74 Filed 05/26/20 Entered 05/26/20 19:45:36 PRESENTMENT DATE: JUNE 11, 2020 AT 12:00 p.m. OBJECTION DEADLINE: JUNE 11, 2020 AT 11:00 a.m. MEYER, SUOZZI, ENGLISH & KLEIN, P.C. TOGUT, SEGAL & SEGAL LLP Edward J. LoBello Frank A. Oswald Howard B. Kleinberg Brian F. Moore Jordan D. Weiss One Penn Plaza, Suite 3335 990 Stewart Avenue, Suite 300 New York, New York 10119 Garden City, New York 11530 (212) 594-5000 (516) 741-6565 Proposed Counsel to the Debtors and Debtors in Possession UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ---------------------------------------------------------------x : In re: : Chapter 11 : RUBIE’S COSTUME COMPANY, INC., et al. : Case No. 20-71970 : Debtors. : (Jointly Administered) : ---------------------------------------------------------------x NOTICE OF PRESENTMENT OF THE DEBTORS’ APPLICATION FOR ENTRY OF AN ORDER AUTHORIZING THE EMPLOYMENT AND RETENTION OF SSG ADVISORS, LLC AS INVESTMENT BANKER FOR THE DEBTORS NUNC PRO TUNC TO THE PETITION DATE PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that on June 11, 2020 at 12:00 p.m. (the “Presentment Date”), Rubie’s Costume Company, Inc. (“Rubies”), Forum Novelties Inc. (“Forum”), Buyseasons Enterprises, LLC (“Buyseasons”), Masquerade, LLC (“Masquerade”), The Diamond Collection LLC (“Diamond Collection”), and Rubie’s Masquerade Company LLC (“Rubie’s Masquerade”), Debtors and Debtors-in-Possession (collectively, the “Debtors”) by their proposed counsel, will present the annexed application (the “Application”) to the Honorable Alan S. Trust, United States Bankruptcy -

Members by Circuit (As of January 3, 2017)

Federal Judges Association - Members by Circuit (as of January 3, 2017) 1st Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit Bruce M. Selya Jeffrey R. Howard Kermit Victor Lipez Ojetta Rogeriee Thompson Sandra L. Lynch United States District Court District of Maine D. Brock Hornby George Z. Singal John A. Woodcock, Jr. Jon David LeVy Nancy Torresen United States District Court District of Massachusetts Allison Dale Burroughs Denise Jefferson Casper Douglas P. Woodlock F. Dennis Saylor George A. O'Toole, Jr. Indira Talwani Leo T. Sorokin Mark G. Mastroianni Mark L. Wolf Michael A. Ponsor Patti B. Saris Richard G. Stearns Timothy S. Hillman William G. Young United States District Court District of New Hampshire Joseph A. DiClerico, Jr. Joseph N. LaPlante Landya B. McCafferty Paul J. Barbadoro SteVen J. McAuliffe United States District Court District of Puerto Rico Daniel R. Dominguez Francisco Augusto Besosa Gustavo A. Gelpi, Jr. Jay A. Garcia-Gregory Juan M. Perez-Gimenez Pedro A. Delgado Hernandez United States District Court District of Rhode Island Ernest C. Torres John J. McConnell, Jr. Mary M. Lisi William E. Smith 2nd Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Barrington D. Parker, Jr. Christopher F. Droney Dennis Jacobs Denny Chin Gerard E. Lynch Guido Calabresi John Walker, Jr. Jon O. Newman Jose A. Cabranes Peter W. Hall Pierre N. LeVal Raymond J. Lohier, Jr. Reena Raggi Robert A. Katzmann Robert D. Sack United States District Court District of Connecticut Alan H. NeVas, Sr. Alfred V. Covello Alvin W. Thompson Dominic J. Squatrito Ellen B. -

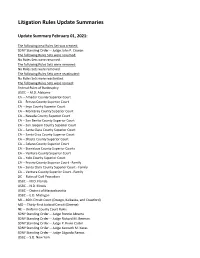

2021-02-01 Litigation Rules Update Summaries

Litigation Rules Update Summaries Update Summary February 01, 2021: The following new Rules Set was created: SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge John P. Cronan The following Rules Sets were renamed: No Rules Sets were renamed. The following Rules Sets were removed: No Rules Sets were removed. The following Rules Sets were reactivated: No Rules Sets were reactivated. The following Rules Sets were revised: Federal Rules of Bankruptcy USDC ‐‐ M.D. Alabama CA ‐‐ Amador County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Fresno County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Inyo County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Monterey County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Nevada County Superior Court CA ‐‐ San Benito County Superior Court CA ‐‐ San Joaquin County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Santa Clara County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Santa Cruz County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Shasta County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Solano County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Stanislaus County Superior Courts CA ‐‐ Ventura County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Yolo County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Fresno County Superior Court ‐ Family CA ‐‐ Santa Clara County Superior Court ‐ Family CA ‐‐ Ventura County Superior Court ‐ Family DC ‐‐ Rules of Civil Procedure USBC ‐‐ M.D. Florida USBC ‐‐ N.D. Illinois USBC ‐‐ District of Massachusetts USBC ‐‐ E.D. Michigan MI ‐‐ 46th Circuit Court (Otsego, Kalkaska, and Crawford) MO ‐‐ Thirty‐First Judicial Circuit (Greene) NE ‐‐ Uniform County Court Rules SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Ronnie Abrams SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Richard M. Berman SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge P. Kevin Castel SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Kenneth M. Karas SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Edgardo Ramos USBC ‐‐ S.D. New York NY Appellate Division, Rules of Practice NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, First Department NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, Second Department NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, Third Department NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, Fourth Department USDC ‐‐ District of North Dakota USDC ‐‐ N.D. -

The “New” District Court Activism in Historical As Umpires, Not Players

39707-nys_72-2 Sheet No. 1 Side A 01/15/2018 10:23:44 \\jciprod01\productn\n\nys\72-2\FRONT722.txt unknown Seq: 1 15-JAN-18 9:55 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY ANNUAL SURVEY OF AMERICAN LAW VOLUME 72 ISSUE 2 39707-nys_72-2 Sheet No. 1 Side A 01/15/2018 10:23:44 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW ARTHUR T. VANDERBILT HALL Washington Square New York City 39707-nys_72-2 Sheet No. 5 Side A 01/15/2018 10:23:44 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYS\72-2\NYS201.txt unknown Seq: 1 15-JAN-18 9:53 THE “NEW” DISTRICT COURT ACTIVISM IN CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM JESSICA A. ROTH* Historically, the debate over the judicial role has centered on the consti- tutional and administrative law decisions of the United States Supreme Court, with an occasional glance at the Federal Courts of Appeals. It has, moreover, been concerned solely with the “in-court” behavior of Article III appellate judges as they carry out their power and duty “to say what the law is” in the context of resolving “cases and controversies.” This Article seeks to deepen the discussion of the appropriate role of Article III judges by broaden- ing it to trial, as well as appellate, judges; and by distinguishing between an Article III judge’s “decisional” activities on the one hand, and the judge’s “hortatory” and other activities on the other. To that end, the Article focuses on a cohort of deeply respected federal district judges-many, although not all, experienced Clinton appointees in the Southern and Eastern Districts of New York–who, over the last decade, have challenged conventional norms of judi- cial behavior to urge reform of fundamental aspects of the federal criminal justice system. -

2020-04-30 Litigation Rules Update Summaries.Xlsx

Litigation Rules Update Summaries Update Summary April 30, 2020: The following new Rules Sets were created: No new Rules Sets were created. The following Rules Sets were renamed: No Rules Sets were renamed. The following Rules Sets were removed: No Rules Sets were removed. The following Rules Sets were reactivated: No Rules Sets were reactivated. The following Rules Sets were revised: 8ENDA USDC ‐‐ N.D. Alabama 4APCR AK ‐‐ Rules of Appellate Procedure ‐ Criminal I3AZN AZ ‐‐ Coconino County Superior Court K3AZA AZ ‐‐ Rules of Civil Appellate Procedure 8TPA CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Percy Anderson 8TXAB CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Andre Birotte Jr. 8TWDK CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge William D. Keller 8TSVW CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Stephen V. Wilson 8TSHS CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Mag. Suzanne H. Segal 0SPJH NDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Chief Judge Phyllis J. Hamilton* 0SPHP NDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Chief Judge Phyllis Hamilton ‐ Patent 0SBLF NDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Beth Labson Freeman 0SJSW NDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Jeffrey S. White 0SJWP NDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Jeffrey S. White ‐ Patent 0SRMI NDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Mag. Robert M. Illman 9SNLS SDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Mag. Nita L. Stormes 4IUCO USDC ‐‐ District of Colorado 7A06C FL ‐‐ 6th Judicial Circuit (Pasco, Pinellas)* 7A06P FL ‐‐ 6th Judicial Circuit ‐ Pinellas County 7A08C FL ‐‐ 8th Judicial Circuit (Alachua, Baker, Bradford, Gilchrist, Levy, Union) 7A17C FL ‐‐ 17th Judicial Circuit (Broward County) 7A18B FL ‐‐ 18th Judicial Circuit ‐ Brevard County 7A18S FL ‐‐ 18th Judicial Circuit ‐ Seminole County 2EFLF FL ‐‐ Family Law Rules of Procedure 1EFAP FL ‐‐ Rules of Appellate Procedure* 2FLA2 FL ‐‐ Second Appellate District 2FLA4 FL ‐‐ Fourth Appellate District 2FLA5 FL ‐‐ Fifth Appellate District L3GBS USBC ‐‐ S.D. -

Federal Judges Association Current Members by Circuit As of 10/8/2020

Federal Judges Association Current Members by Circuit as of 10/8/2020 1st Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit Jeffrey R. Howard 0 Kermit Victor Lipez (Snr) Sandra L. Lynch Ojetta Rogeriee Thompson United States District Court District of Maine D. Brock Hornby (Snr) 0 Jon David Levy George Z. Singal (Snr) Nancy Torresen John A. Woodcock, Jr. (Snr) United States District Court District of Massachusetts Allison Dale Burroughs 0 Denise Jefferson Casper Timothy S. Hillman Mark G. Mastroianni George A. O'Toole, Jr. (Snr) Michael A. Ponsor (Snr) Patti B. Saris F. Dennis Saylor Leo T. Sorokin Richard G. Stearns Indira Talwani Mark L. Wolf (Snr) Douglas P. Woodlock (Snr) William G. Young United States District Court District of New Hampshire Paul J. Barbadoro 0 Joseph N. Laplante Steven J. McAuliffe (Snr) Landya B. McCafferty Federal Judges Association Current Members by Circuit as of 10/8/2020 United States District Court District of Puerto Rico Francisco Augusto Besosa 0 Pedro A. Delgado Hernandez Daniel R. Dominguez (Snr) Jay A. Garcia-Gregory (Snr) Gustavo A. Gelpi, Jr. Juan M. Perez-Gimenez (Snr) United States District Court District of Rhode Island Mary M. Lisi (Snr) 0 John J. McConnell, Jr. William E. Smith 2nd Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Jose A. Cabranes 0 Guido Calabresi (Snr) Denny Chin Christopher F. Droney (Ret) Peter W. Hall Pierre N. Leval (Snr) Raymond J. Lohier, Jr. Gerard E. Lynch (Snr) Jon O. Newman (Snr) Barrington D. Parker, Jr. (Snr) Reena Raggi (Snr) Robert D. Sack (Snr) John M. -

1989 Journal

OCTOBER TERM, 1989 Reference Index Contents: Page Statistics n General m Appeals in Arguments in Attorneys in Briefs iv Certiorari iv Costs v Judgments and Opinions v Miscellaneous v Original Cases v Parties vi Records vi Rehearings vi Rules vi Stays vi Conclusion vn (i) II STATISTICS AS OF JUNE 28, 1990 In Forma Paid Oripnal Pauperis Total Cases Cases Number of cases on docket 14 2,416 3,316 5,746 Cases disposed of 2 2,051 2,879 4,932 Remaining on docket 12 365 437 814 Cases docketed during term: Paid cases 2,032 In forma pauperis cases 2,885 Original cases 1 Total 4,918 Cases remaining from last term 828 Total cases on docket 5,746 Cases disposed of 4,932 Number of remaining on docket 814 Petitions for certiorari granted: In paid cases 100 In in forma pauperis cases 19 Appeals granted: In paid cases 3 In in forma pauperis cases 0 Total cases granted plenary review 123* Cases argued during term 146 Number disposed of by full opinions 143 Number disposed of by per curiam opinions 3 Number set for reargument next term 0 Cases available for argument at beginning of term 81 Disposed of summarily after review was granted 1 Original cases set for argument 1 Cases reviewed and decided without oral argument 79 Total cases available for argument at start of next term 57 Number of written opinions of the Court 129 Opinions per curiam in argued cases 3 Number of lawyers admitted to practice as of October 1, 1990: On written motion 4,623 On oral motion 1,173 Total 5,796 *Includes 74, Original. -

A Retrospective (1990-2014)

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York: A Retrospective (1990-2014) The New York County Lawyers Association Committee on the Federal Courts May 2015 Copyright May 2015 New York County Lawyers Association 14 Vesey Street, New York, NY 10007 phone: (212) 267-6646; fax: (212) 406-9252 Additional copies may be obtained on-line at the NYCLA website: www.nycla.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE COURT (1865-1990)............................................................ 3 Founding: 1865 ........................................................................................................... 3 The Early Era: 1866-1965 ........................................................................................... 3 The Modern Era: 1965-1990 ....................................................................................... 5 1990-2014: A NEW ERA ...................................................................................................... 6 An Increasing Docket .................................................................................................. 6 Two New Courthouses for a New Era ........................................................................ 7 The Vital Role of the Eastern District’s Senior Judges............................................. 10 The Eastern District’s Magistrate Judges: An Indispensable Resource ................... 11 The Bankruptcy -

Dinner Journal

Hon. William C. Conner Inn of Court Reception and Dinner January 19, 2010 The Union League Club of New York In Memoriam On behalf of the Officers and Executive Committee of the Hon. William C. Conner Inn of Court, it is with great sadness that we report the pass- ing of the Hon. William C. Conner on July 9, 2009. He was 89. Judge Conner served his country with distinction as a United States District Court Judge of the Southern District of New York for over 35 years. He was a valued member of our IP community as a patent attor- ney (1946-73), as a past president of the New York Intellectual Property Law Association (1972-73), then known as the New York Patent Law Association, and most recently as emeritus and active judicial partici- pant in our Conner Inn of Court. He will be deeply missed. Tributes to Judge Conner have been collected and posted on the Con- ner Inn website at www.connerinn.org. Judge William C. Conner Mission of the Hon. William C. Conner Inn of Court The mission of the Hon. William C. Conner Inn of Court is to promote excellence in professionalism, ethics, civility, and legal skills for judges, lawyers, academicians, and students of law and to advance the education of the members of the Inn, the members of the bench and bar, and the public in the fields of intellectual property law. Program w w w Cocktail Reception • 6:00 pm w w w w w w Dinner • 7:00 pm w w w w w w Welcome w w w Anthony Giaccio w w w Presentations w w w Conner Inn Excellence Award to Chief Judge Loretta A. -

A U G U S T 2 0

AUGUST 2020 AUGUST 2020 AUGUST 2020 When trailblazer Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was in law school in the 1950s, women were less than 3% of lawyers in the country. Today, she observed, they occupy more than 50% of law school classes. But women represent only 33% of active federal judges. We can hope that their numbers will rise to reflect the important contributions they make to the legal profession. This year, in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, securing women’s right to vote, the Second Circuit was poised to devote its judicial conference to the subject of women in the law, under the dynamic leadership of Judge Victor Bolden of the District of Connecticut. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the conference was canceled. But much good work was done in preparation for that conference by our planning committee and our Library team. Among the fruits of their labor is compendium of short biographies of the women judges of the courts of the Second Circuit. How fortunate all of us are to have the services of such distinguished jurists. Our Circuit’s civic education project, Justice For All: Courts and the Community, will continue to devote attention to the role and contributions of our women judges to our nation. Chief Judge Robert A. Katzmann July 2020 AUGUST 2020 AUGUST 2020 CIRCUIT JUSTICE for the SECOND CIRCUIT RUTH BADER GINSBURG Education Cornell University, B.A., 1954. Columbia Law School, LL.B., 1959. Professional Career Research associate; associate director, Columbia Law Project on International Procedure, 1961–1963. -

Judicial Nominations by President Clinton During the 103Rd-106Th Congresses

Order Code 98-510 GOV Judicial Nominations by President Clinton During the 103rd-106th Congresses Updated September 20, 2006 Denis Steven Rutkus Specialist in American National Government Government and Finance Division Judicial Nominations by President Clinton During the 103rd-106th Congresses Summary Under the Constitution of the United States, the President nominates and, subject to confirmation by the Senate, appoints justices to the Supreme Court and judges to nine other court systems. Altogether, during the 103rd–106th Congresses, President Bill Clinton transmitted to the Senate: ! two Supreme Court nominations, both of which were confirmed during the 103rd Congress; ! 106 nominations to the U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals, of which 65 were confirmed; ! 382 nominations to the U.S. District Courts (including the territorial district courts), of which 307 were confirmed; ! six nominations to the U.S. Court of International Trade, five of which were confirmed; ! the names of seven nominees to the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, all of whom received Senate confirmation; ! the names of nine nominees to the U.S. Tax Court, all of whom were confirmed; ! one nomination to the U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, which was confirmed during the 105th Congress; ! the names of 24 nominees to the Superior Court of the District of Columbia, 22 of whom were confirmed; ! five nominations to the District of Columbia Court of Appeals, four of which were confirmed; ! and two nominations to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, both of which were confirmed. Most nominations that failed to be confirmed were returned to the President after the Senate adjourned or recessed for more than 30 days. -

Judicial Nominations by President Clinton During the 103Rd and 104Th Congresses

96-567 GOV Judicial Nominations by President Clinton During the 103rd and 104th Congresses Updated January 24, 1997 Denis Steven Rutkus Specialist in American National Government Government Division -- CRS Judicial Nominations by President Clinton During the 103rd and 104th Congresses SUMMARY Under the Constitution of the United States, the President nominates, and subject to confirmation by the Senate, appoints Justices to the Supreme Court as well as judges to nine other courts or court systems. Altogether during the 103rd and 104th Congresses, President William Jefferson Clinton transmitted to the Senate: 0 two Supreme Court nominations, both of which were confirmed during the 103rd Congress; e 42 nominations to the U.S. Courts of Appeals, 30 of which were confirmed; e 204 nominations to the U.S. District Courts, 170 of which were confirmed; e two nominations to the U.S. Court of International Trade, both of which were confirmed during the 104th Congress; e one nomination to the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, which, after referral to committee, advanced no further in the Senate and was returned to the President at the end of the 104th Congress; e the names of four nominees to the U.S. Tax Court, two of whom were nominated twice (first in the 103rd Congress, and again in the 104th Congress) and all of whom eventually were confirmed; 0 eleven nominations to the Superior Court of the District of Columbia, nine of which were confirmed; * two nominations to the District of Columbia Court ofAppeals, both of which were confirmed; and one nomination to the U.S.