ROWLEY Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

End Of Year Charts 2006 CHART #20061111 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Crazy Based On A True Story 1 Gnarls Barkley 1 Fat Freddy's Drop Last week 0 / 0 weeks WEA/Warner Last week 0 / 0 weeks TheDrop/Rhythmethod Beep Back To Bedlam 2 The Pussycat Dolls feat. Will.I.Am 2 James Blunt Last week 0 / 0 weeks Universal Last week 0 / 0 weeks WEA/Warner Bathe In The River Stadium Arcadium 3 Mt Raskill PS feat. Hollie Smith 3 Red Hot Chili Peppers Last week 0 / 0 weeks EMI Last week 0 / 0 weeks WEA/Warner Hips Don't Lie All The Right Reasons 4 Shakira feat. Wyclef Jean 4 Nickelback Last week 0 / 0 weeks SBME Last week 0 / 0 weeks Roadrunner/Universal Run It! High School Musical OST 5 Chris Brown 5 Various Last week 0 / 0 weeks SBME Last week 0 / 0 weeks Disney/EMI Promiscuous PCD 6 Nelly Furtado feat. Timbaland 6 The Pussycat Dolls Last week 0 / 0 weeks Universal Last week 0 / 0 weeks Universal Touch It Eyes Open 7 Busta Rhymes 7 Snow Patrol Last week 0 / 0 weeks Universal Last week 0 / 0 weeks Universal Buttons Eye To The Telescope 8 The Pussycat Dolls feat. Snoop Dogg 8 KT Tunstall Last week 0 / 0 weeks Universal Last week 0 / 0 weeks Virgin/EMI SexyBack Ring Of Fire: The Legend Of 9 Justin Timberlake 9 Johnny Cash Last week 0 / 0 weeks SBME Last week 0 / 0 weeks Universal Ridin' Sing-Alongs And Lullabies 10 Chamillionaire feat. Tyree 10 Jack Johnson Last week 0 / 0 weeks Universal Last week 0 / 0 weeks Universal I'm In Luv (Wit A Stripper) 10,000 Days 11 T-Pain feat. -

Proquest Dissertations

FRONTIERS, OCEANS AND COASTAL CULTURES: A PRELIMINARY RECONNAISSANCE by David R. Jones A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary's University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Atlantic Canada Studues December, 2007, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright David R. Jones Approved: Dr. M. Brook Taylor External Examiner Dr. Peter Twohig Reader Dr. John G. Reid Supervisor September 10, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46160-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46160-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Editorial Standards Committee Bulletin, Issued February 2017

Editorial Standards Findings Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered by the Editorial Standards Committee March 2017, issued March 2017 Decisions by the Head of Editorial Standards, Trust Unit February and March 2017 issued March 2017 Getting the best out of the BBC for licence fee payers Contents Contents 1 Remit of the Editorial Standards Committee 2 Summary of Appeal Findings 4 Panorama: Pensions Rip Offs Exposed, BBC One, 11 July 2016 4 Good Morning Scotland, BBC Radio Scotland, 4 November 2016 5 Good Morning Scotland, BBC Radio Scotland, 31 March 2016 7.36am 6 Appeal Findings 8 Panorama: Pensions Rip Offs Exposed, BBC One, 11 July 2016 8 Good Morning Scotland, BBC Radio Scotland, 4 November 2016 21 Good Morning Scotland, BBC Radio Scotland, 31 March 2016 7.36am 26 Appeals against the decisions of BBC Audience Services not to correspond further with the complainant 32 Decision of BBC Audience Services not to respond further to a complaint about taking down a photograph from BBC News Online 33 Decision of BBC Audience Services not to respond further to a complaint about BBC News coverage of the Labour Party 36 Admissibility decisions by the Head of Editorial Standards, Trust Unit 44 Decision of Audience Services not to respond further to a complaint about BBC News at Six, 31 August 2016 45 Decision of Audience Services not to respond further to a complaint about Chris Packham’s personal use of Twitter on 5 & 8 January and 12 February 2017 49 Decision of Audience Services not to respond further to a complaint about -

She Said What? Interviews with Women Newspaper Columnists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Women's Studies Gender and Sexuality Studies 4-7-1993 She Said What? Interviews with Women Newspaper Columnists Maria Braden University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Braden, Maria, "She Said What? Interviews with Women Newspaper Columnists" (1993). Women's Studies. 2. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_womens_studies/2 SHE SAID WHAT? This page intentionally left blank SHE SAID WHAT? Interviews with Women Newspaper Columnists MARIA BRADEN THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1993 by Maria Braden Published by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8131-9332-8 (pbk: acid-free paper) This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

It's Official

ALUMNI TRAVEL WRITERS It’s Official \ CHARLES WHITAKER JEFFREY ZUCKER SCHOLARSHIPS IS DEAN OF MEDILL \ IMC IN SAN FRANCISCO SUMMER/FALL 2019 \ ISSUE 101 \ ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTENTS \ Congratulations to Max Bearak EDITORIAL STAFF DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI of the Washington Post RELATIONS AND ENGAGEMENT Belinda Lichty Clarke (MSJ94) MANAGING EDITOR Winner of the 2018 James Foley Katherine Dempsey (BSJ15, MSJ15) DESIGN Medill Medal for Courage in Journalism Amanda Good COVER PHOTOGRAPHER Colin Boyle (BSJ20) PHOTOGRAPHER Jenna Braunstein CONTRIBUTORS Erin Chan Ding (BSJ03) Kaitlyn Thompson (BSJ11, IMC17) Nikhila Natarajan (IMC19) Mary Neil Crosby (MSJ89) 11 MEDILL HALL OF 18 THINKING ACHIEVEMENT CLEARLY ABOUT 2019 INDUCTEES MARTECH Medill welcomes five inductees Course in San Francisco into its Hall of Achievement. helps students ask the right MarTech questions. 14 JEFFREY ZUCKER SCHOLARSHIPS 20 MEDILLIAN Two new funds aim to TRAVEL foster the next generation WRITERS of journalists. Alumni work in travel-focused positions that encourage others to explore the world. 16 MEDILL WOMEN The Nairobi Bureau Chief won for his reporting from sub-Saharan Africa. IN MARKETING PANEL 24 AN AMERICAN His stories from Congo, Niger and Zimbabwe chronicled a wide range of SUMMER Panel event with female extreme events that required intense bravery in dangerous situations PLEASE SEND STORY PITCHES alumni provides career advice. Faculty member Alex AND LETTERS TO: Kotlowitz sheds light on without being reckless or putting himself at the center of the story, new book. 1845 Sheridan Rd. said the judges, who were unanimous in their decision. Evanston, IL 60208 [email protected] 5 MEDILL NEWS / 26 CLASS NOTES / 30 OBITUARIES / 36 KEEP READING .. -

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 7/8/2020 Semisonic “You’re Not Alone” The first single from their You’re Not Alone EP, out 9/18 BDS Monitored #1 Most Added before add week! Early: KCMP, KCSN, WRNR, WXPK, WFUV, WTMD, WFPK, KTBG, Music Choice, WPYA, WOCM, KYSL, WFIV, WJCU, KNBA, KSLU, WUKY, WOXL This is their first new music in almost 20 years Tons of great press “Like their greatest hits of yesteryear” - Consequence of Sound Margo Price “Letting Me Down” The first single That’s How Rumors Get Started, produced by Sturgill Simpson, out this Friday Appeared on CBS This Morning BDS Monitored New & Active, JBE Tracks 49*, Public 23*! New: WEVL ON: WRLT, WFUV, WXPN, Music Choice, WYEP, WFPK, WTMD, KTBG, KJAC, WRSI and more Tons of recent and upcoming press Watch the creative video on my site now Buzzard Buzzard Buzzard “Double Denim Hop” The first single from The Non-Stop EP, out this Friday New: WCNR, WYCE ON: KCSN, KJAC, WCLX, WCBE, WBJB, WOCM, WFIV, KROK “Think Thin Lizzy or T-Rex in the back room of a pub, riffs and tunes intact but with an endearing slacker attitude.” - The Guardian Great UK press! Topping the Alt Press list of the Best New British Guitar-Rock Bands: “Theirs is the ground floor to be on, friends.” Joshua Speers “Bad Night” From his Human Now EP, out now New: WYCE, KROK, WCBE, KSLU ON: KSMF, KCLC, WFIV, KUWR “The five-track project is such an enamoring listen, kind of perfect for quarantine, whether with a cup of coffee—or whiskey.. -

Music Preview

JACKSONVILLE NING! OPE entertaining u newspaper change your free weekly guide to entertainment and more | february 15-21, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com life in 2007 2 february 15-21, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper table of contents cover photo of Paul Paxton by: Dennis Ho feature NASCAR Media Day ............................................................................PAGES 16-17 Local Music Preview ...........................................................................PAGES 18-24 movies Breach (movie review) .................................................................................PAGE 6 Movies In Theatres This Week .................................................................PAGES 6-9 Seen, Heard, Noted & Quoted .......................................................................PAGE 7 Hannibal Rising (movie review) ....................................................................PAGE 8 The Last Sin Eater (movie review) ................................................................PAGE 9 Campus Movie Fest (Jacksonville University) ..............................................PAGE 10 Underground Film Series (MOCA) ...............................................................PAGE 10 at home The Science Of Sleep (DVD review) ...........................................................PAGE 12 Grammy Awards (TV Review) .....................................................................PAGE 13 Video Games .............................................................................................PAGE 14 food -

Townhall.Com::Dixie Chicks, Dissent, and "Whacked" Paranoia::By Jon

Townhall.com::Dixie Chicks, dissent, and "whacked" paranoia::By Jon ... http://www.townhall.com/Columnists/JonSanders/2007/02/13/dixie_chic... Email Address What's Hot | Search Login | About Us | Sitemap Blog | Talk Radio Online | Columnists | Your Blogs | The News | Photos | The Funnies | Books & Movies | Issues | Sign Up | Radio Schedule | Action Center | Home Mike Gallagher | Mary Katharine Ham | Hugh Hewitt | Michael Medved | Michael Barone | Bruce Bartlett | Tony Blankley | Kevin McCullough | Dennis Prager | More [+] Bill Bennett • Mike Gallagher • Dennis Prager • Michael Medved • Hugh Hewitt Listen Now To 990 AM WNTP! ON THE BLOG NOW: Dixie Chicks, dissent, Email It and "whacked" paranoia Updated at 3:20 PM Print It By Jon Sanders Hillary's Campaign Poster, II Tuesday, February 13, 2007 Take Action Updated: 2:42 PM 02/13/07 Send an email to Jon Sanders Maliki "wises up" will shut borders with Iran and Syria! nmlkj Yes nmlkj No Updated: 1:26 PM 02/13/07 Read Article & Comments (133) Trackbacks(0) Post Your Comments I Knew Bushitler Couldn't Really Love His Wife nmlkj Yes nmlkj No Updated: 1:08 PM 02/13/07 "I think people are paranoid" was how former Grateful Dead member God Is on Everybody's Side Mickey Hart's comments to Reuters began. Hart was speaking about this Updated: 12:36 PM 02/13/07 year's Grammy Awards and the Dixie Chicks. Then he provided a sterling nmlkj Yes nmlkji No Iran WILL HAVE nukes says example of that very paranoia. EU document... Updated: 12:34 PM 02/13/07 "I think that if they speak out, they think they're gonna get whacked by the government. -

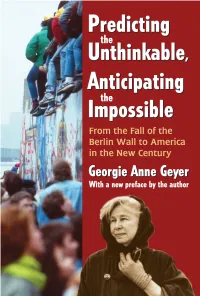

Predicting the Unthinkable, Anticipating the Impossible

First published 2011 by Transaction Publishers Published 2017 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 2011 by Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2013009660 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Geyer, Georgie Anne, 1935- Predicting the unthinkable, anticipating the impossible : from the fall of the Berlin Wall to America in the new century / Georgie Anne Geyer, with a new preface by the author. pages cm “New material this edition copyright (c) 2013 by Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, New Jersey. Originally published in 2011 by Transaction Publishers.” ISBN 978-1-4128-5278-4 1. World politics--1989- 2. United States--Foreign relations--1989- I. Title. D860.G524 2013 909.82’9--dc23 2013009660 ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-5278-4 (pbk) ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-1487-4 (hbk) Contents Preface to the Paperback Edition by Georgie Anne Geyer xi Preface by Irving Louis Horowitz xvii Acknowledgments xxiii -

Popular Music and Violence This Page Has Been Left Blank Intentionally Dark Side of the Tune: Popular Music and Violence

DARK SIDE OF THE TUNE: POPULAR MUSIC AND VIOLENCE This page has been left blank intentionally Dark Side of the Tune: Popular Music and Violence BRUCE JOHNSON University of Turku, Finland Macquarie University, Australia University of Glasgow, UK MARTIN CLOONAN University of Glasgow, UK © Bruce Johnson and Martin Cloonan 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Bruce Johnson and Martin Cloonan have asserted their moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington, VT 05401-4405 Surrey GU9 7PT USA England www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Johnson, Bruce, 1943– Dark side of the tune : popular music and violence. – (Ashgate popular and folk music series) 1. Music and violence 2. Popular music – Social aspects I. Title II. Cloonan, Martin 781.6'4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Johnson, Bruce, 1943– Dark side of the tune : popular music and violence / Bruce Johnson and Martin Cloonan. p. cm.—(Ashgate popular and folk music series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-7546-5872-6 (alk. paper) 1. Music and violence. 2. Popular music—Social aspects. I. Cloonan, Martin. II. Title. -

Title Format Released Abyssinians, the Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin

Title Format Released Abyssinians, The Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin, Barbara The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 2) CD 2002 The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 1) CD 2002 Adams Johnny Johnny Adams Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me CD 1991 Adams, Johnny I Won't Cry CD 1991 Walking On A Tightrope - The Songs Of Percy Mayfield CD 1989 Good Morning Heartache CD 1993 Ade & His African Beats, King Sunny Juju Music CD 1982 Ade, King Sunny Odu CD 1998 Alabama Feels So Right CD 1981 Alexander, Arthur Lonely Just Like Me CD 1993 Allison, DeAnn Tumbleweed CD 2000 Allman Brothers Band, The Beginnings CD 1971 American Song-poem Anthology, The Do You Know The Difference Between Big Wood And Brush CD 2003 Animals, The Animals - Greatest Hits CD 1983 The E.P. Collection CD 1964 Aorta Aorta CD 1968 Astronauts, The Down The Line/ Travelin' Man CD 1997 Competition Coupe/Astronauts Orbit Kampus CD 1997 Rarities CD 1991 Go Go Go /For You From Us CD 1997 Surfin' With The Astronauts/Everything Is A-OK! CD 1997 Austin Lounge Lizards Paint Me on Velvet CD 1993 Average White Band Face To Face - Live CD 1997 Page 1 of 45 Title Format Released Badalamenti, Angelo Blue Velvet CD 1986 Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me CD 1992 Badfinger Day After Day [Live] CD 1990 The Very Best Of Badfinger CD 2000 Baker, Lavern Sings Bessie Smith CD 1988 Ball, Angela Strehli & Lou Ann Barton, Marcia Dreams Come True CD 1990 Ballard, Hank Sexy Ways: The Best of Hank Ballard & The Midnighters CD 1993 Band, The The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down: The Best Of The Band [Live] CD 1992 Rock Of Ages [Disc 1] CD 1990 Music From Big Pink CD 1968 The Band CD 1969 The Last Waltz [Disc 2] CD 1978 The Last Waltz [Disc 1] CD 1978 Rock Of Ages [Disc 2] CD 1990 Barker, Danny Save The Bones CD 1988 Barton, Lou Ann Read My Lips CD 1989 Baugh, Phil 64/65 Live Wire! CD 1965 Beach Boys, The Today! / Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) CD 1990 Concert/Live In London [Bonus Track] [Live] CD 1990 Pet Sounds [Bonus Tracks] CD 1990 Merry Christmas From The Beach Boys CD 2000 Beatles, The Past Masters, Vol. -

111111' COBA Dedication Underway

Thursday, September 21, 1995 • Vol. XXVII No. 24 TilE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY'S Geyer: Journalists 'chained' to desks By KAREN BELL Vietnam, but with Cambodia News Writer and the uprising of guerilla warfare and militia. J "If you have a terrible war The perils of the job have with 2000 people trying to get reached life threatening pro out and 12 trying to get in, the portions today. r 12 will be the foreign corre In fact, 1994 was the bloodi spondents." est year in the profession with Georgie Anne Geyer, an au 115 deaths: being deliberately 111111' thor and syndicated columnist, targeted, they are more often delivered the annual Red Smith slaughtered in the most primi lllr· L.ecture i.n Journalism last tive of ways with axe and knife. ____ evening in the llesburgh Li Meanwhile, at home, due to brary Auditorium. financial pressures, papers Entitled, "Who Killed the were being closed or merged as Ill Foreign Correspondent?", the computers took over, si Geyer spoke of how journalists, phoning information from the often seen as a dying breed, are superhighway. becoming chained by the infor mation superhighway at the Epitomizing the change, expense of adventure and con Geyer saw the CNN coverage of text. the Gulf war as rather like a When they do "parachute" story without images. 3000 into the outside world, they journalists sent out stories, but simply capture a mere glimpse had no knowledge of the area, of the reality they can put culture or language; in essence, The Observer/Mike Ruma together in just a few hours.