James Earl Rudder and the Coeducation of Texas A&M University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Day. As Bush School Dean Mark Welsh Said in His Opening Remarks, 600 World War II Veterans Are Lost Each Day According to Some Accounts

“First Wave” with Alex Kershaw Sept. 19, 2019 By Trenton Spoolstra This past June marked the 75th anniversary of Operation Overlord, better known as D- Day. As Bush School Dean Mark Welsh said in his opening remarks, 600 World War II veterans are lost each day according to some accounts. The day will soon come when World War II will no longer be recounted by those who fought in it. Much has been written about D-Day, such as the complex planning, the incredible logistical requirements, and the maneuvers needed to advance off the beach. The human aspect is often buried. Mr. Kershaw offered fascinating and stirring personal accounts of a few men who jumped behind enemy lines, landed gliders, and stormed the beaches. Frank Lillyman was the first American to land in Normandy. Lillyman had made fifty- three practice jumps before jumping into the dark skies at 12:15am on June 6th. He was known by his men for his ever-present cigar – even while exiting the door of the aircraft. Captain Leonard Schroeder was the first American to come ashore early that morning. Schroder’s nickname was “Moose,” and he was a good friend of 56 year-old Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., the son of the famous early twentieth century president and the oldest soldier in the first wave on Utah beach. He earned the Distinguished Service Cross for bravery. A few weeks later, Roosevelt had a massive heart attack and was buried in Saint-Mere-Eglise. He was later moved the American cemetery in Normandy, and his award for heroism was upgraded to the Medal of Honor. -

1 the Boys of Pointe Du Hoc by Senator Tom Cotton Introduction When Describing Major Military Undertakings, Writers Often Emphas

The Boys of Pointe du Hoc By Senator Tom Cotton Introduction When describing major military undertakings, writers often emphasize their immensity. Shakespeare in Henry V, for example, invites his audience to imagine the king’s massive fleet embarking on its invasion of Normandy in 1415. “You stand upon the rivage and behold,” the chorus intones, “A city on the inconstant billows dancing, / For so appears this fleet majestical.”1 Nearly 600 years later, the British military historian John Keegan described what he beheld as a 10-year-old schoolboy on June 5, 1944, when the night sky pulsed with the noise of prop engines. Its first tremors had taken my parents into the garden, and as the roar grew I followed and stood between them to gaze awestruck at the constellation of red, green and yellow lights, which rode across the heavens and streamed southward across the sea. It seemed as if every aircraft in the world was in flight, as wave followed wave without intermission . [W]e remained transfixed and wordless on the spot where we stood, gripped by a wild surmise of what power, majesty, and menace the great migratory flight could portend.2 Keegan did not know at the time that he was witnessing the Allies’ “great adventure” in Europe, as his nation’s General Bernard Montgomery called it. Somewhat more memorably, General Dwight Eisenhower dubbed it the “Great Crusade.” Operation Overlord had begun, and with it the fight to liberate Europe from Nazi tyranny. Both Keegan and Shakespeare stressed the massive scale of these cross-Channel invasions. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

E1708 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks September 8, 2008 garnered Illinois State Player of the Year hon- Nevertheless, receiving that award has always that day, our world survived the tyranny of ors and led his team to a State championship been a source of deep humility to me, be- Adolf Hitler. Lieutenant Colonel Rudder, this in 2001. He then went on to Pepperdine Uni- cause I know that I could not even walk in the great Aggie and American, didn’t stop there. versity, where he became one of their top shadows of this great American’s shoes. He went on to lead a unit in the Battle of the players and helped lead them to a national I want to salute the school board members, Bulge and became one of the most decorated championship in 2005. After graduating in Superintendent Cargill, Principal Piatt, and all veterans of World War II. 2005, Sean continued to pursue his love of who made this new school possible. James Having every right to say his public service the sport, playing professionally for 2 years. Earl Rudder High School is far more than was completed at the end of World War II, Then, Sean was selected to represent his brick, glass, and mortar, because a school Earl Rudder did what so many of America’s country on the international stage as a mem- represents the very best of our values as a veterans have done throughout our history. He ber of the United States’ Men’s Indoor community. This school represents the com- spent the rest of his life in service to others Volleyball Team in the Games of the XXIX mitment of one generation to the next. -

Test Your Trivia Here

EATS & TREATS: September 2011 A GUIDE TO FOOD & FUN HOW MANY AGGIE TEAMS WON NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS IN 2010? NAME 5 TEXAS A&M ATHLETES WHAT IS THE OLDEST BUSINESS WHO NOW HAVE PRO SPORTS CAREERS ESTABLISHMENT IN COLLEGE STATION? TEST YOUR B RAZ OS VALLEY TRIVIA HERE September 2011 INSITE 1 2 INSITE September 2011 20 CONTENTS 5 MAKINGHISTORY Headed to the White House New exhibit shows what it takes to become President by Tessa K. Moore 7 LIFESTYLE Wanted: Texas Hospitality Families can share much with Aggies far from home by Tessa K. Moore 9 COMMUNITYOUTREACH A Legacy of Love Bubba Moore Memorial Group keeps the giving spirit alive by Megan Roiz INSITE Magazine is published monthly by Insite 11 GETINVOLVED Printing & Graphic Services, 123 E. Wm. J. Bryan Pkwy., Everyone Needs a Buddy Bryan, Texas 77803. (979) Annual walk raises more than just funds 823-5567 www.insitegroup. by Caroline Ward com Volume 28, Number 5. Publisher/Editor: Angelique Gammon; Account Executive: 12 ARTSSPOTLIGHT Myron King; Graphic Wanted: Dramatis Personae Designers: Alida Bedard; Karen Green. Editorial Or, How to get your Glee on around the Brazos Valley Interns: Tessa K. Moore, by Caroline Ward Megan Roiz, Caroline Ward; INSITE Magazine is a division of The Insite Group, LP. 15 DAYTRIP Reproduction of any part Visit Houston without written permission Find the metro spots that only locals know of the publisher is prohibited. Insite Printing & Graphic Services Managing Partners: 19 MUSICSCENE Kyle DeWitt, Angelique Beyond Price Gammon, Greg Gammon. Chamber concerts always world class, always free General Manager: Carl Dixon; Pre-Press Manager: Mari by Paul Parish Brown; Office Manager: Wendy Seward; Sales & Customer Service: Molly 20 QUIZTIME Barton; Candi Burling; Janice Feeling Trivial? Hellman; Manda Jackson; Test your Brazos Valley Trivia IQ Marie Lindley; Barbara by Tessa K. -

Hyatt Regency Greenville, South Carolina June 6 - 8, 2019

Hyatt Regency Greenville, South Carolina June 6 - 8, 2019 The SC Engineering Conference & Trade Show will be Additionally, the conference offers a trade show where celebrating its twelfth year in 2019. products and services that engineers use are offered by knowledgeable representatives to assist participants. This year, the Conference will be in the SC Upstate in hopes of tapping the resources of South Carolinas Piedmont Conferences are always about more than technical programs engineers, companies and industry. and trade shows; the 2019 SC Engineering Conference & Trade Show also realizes the importance of opportunities to This year, engineers attending the conference June 6-8 at the meet and converse with fellow professionals. An exhibitor Hyatt Regency Greenville may gain up to 15 PDHs and reception on Thursday evening serves as a networking choose from a variety of more than 50 programs. opportunity between engineers and exhibitors. Session The mission of the SC Engineering Conference is “timely breaks, lunches and the banquet are also great times for presentations on various engineering subjects, keynote meeting and talking with fellow professionals. presentations and enough professional development hours to substantially meet the annual requirement.” The 2019 SC Engineering Conference & Trade Show is offering 15 PDH. For attending a program in every time slot, you will be able to accumulate 15 PDH of the 15 required annually. Wednesday, June 5, 2019 1:00 PM – 3:00 PM ....................................................................................... ***OPTIONAL*** EDUCATION SPONSOR If interested in this presentation, you must RSVP separately for this event/class. Class size limited to 30 People. Historical Structure Restoration Using Tradition Methods of Blacksmithing George McCall, PE, McCall and Son and SC State Board of Registration for James Mosley, The Heirloom Companies. -

Rudder's Rangers Company History…

Rudder’s Rangers Company History… So Far There is much history surrounding Rudder’s Rangers and its forty plus years of existence. Some is fact, some is exaggeration, and some is mere fiction. The reason why nobody knows for sure everything about Rudder’s Rangers is because there has never been a systematic attempt, until now, to capture its rich and vibrant history. Rudder’s Rangers was originally founded in either 1968 or 1970 as the “Texas A&M Ranger Company” by members of company F-2. Its original purpose was to serve as an opposing force (OPFOR) unit for Texas A&M Army ROTC. There are also rumors floating about that it was originally founded as a protest to the Vietnam War but these have not been confirmed. Over time though, the Texas A&M Ranger Company took on the additional mission of training cadets to attend Ranger School in-between their sophomore and junior years in lieu of the Leader Development and Assessment Course or LDAC. Back then, select cadets (as determined by a national order of merit list) could attend Ranger School and, assuming they passed, would earn the highest score possible at LDAC (a “5” at the time, but later an “E”). Texas A&M Ranger Company cadets were often selected to attend and excelled at Ranger School. Perhaps some of the reason to this was that, prior to leaving for Ranger School, cadets were instructed to sign transfer papers to Texas A&M Prairie View. They were told that, if they failed, not to worry because their transfer papers would be waiting for them once they got back! However, not all was bliss for the Texas A&M Ranger Company. -

Second Circular

All black and white photographs courtesy of Cushing Memorial Library and Archives, Texas A&M University In 1964, Texas Governor John B. Connally personally visited the Texas A&M University campus to deliver the good news to then-Texas A&M President James Earl Rudder '32 that a $6 million "atom smasher" would be built at Texas A&M. On December 4, 1967, Nobel Prize winners Glenn T. Seaborg and Willard F. Libby helped dedicate the Texas A&M Cyclotron Institute — three days after it had achieved its first external cyclotron-accelerated particle beam, thanks to a 400-ton, 2,000-kilowatt magnet whose power was equivalent to one-fifth of the output of the Texas A&M Power Plant. Join us throughout 2017 as the Cyclotron Institute commemorates 50 years of beam with a series of c elebratory activities set to culminate in a November 15-17 symposium dedicated to our past, present, and future of exploring the nuclear frontier. http://cyclotron.tamu.edu/50years/ Second Circular We are pleased to announce an international symposium celebrating 50 Years of Beam at the Cyclotron Institute at Texas A&M University. The symposium will be held November 15–17, 2017 on the campus of Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas, USA. Program The title of the symposium is Exploring the Nuclear Frontier: 50 Years of Beam. The scientific program will feature talks focusing on the research areas of current interest to the Cyclotron Institute: • Nuclear Structure, Reactions, and the Equation of State • Fundamental Symmetries • High-Energy Nuclear Physics • Applications of Cyclotron-Based Nuclear Science In addition to the scientific program, we will have historical talks given by former Cyclotron Institute directors on Thursday and a celebration BBQ on Friday. -

From the Inside Looking In: Tradition and Dviersity At

FROM THE INSIDE LOOKING IN: TRADITION AND DVIERSITY AT TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY A Thesis by EMILY LYNN CAULFIELD Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Major Subject: Communication FROM THE INSIDE LOOKING IN: TRADITION AND DIVERSITY AT TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY A Thesis by EMILY LYNN CAULFIELD Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Eric Rothenbuhler Committee Members, Leroy Dorsey Robert Mackin Head of Department, Richard Street May 2008 Major Subject: Communication iii ABSTRACT From the Inside Looking In: Tradition and Diversity at Texas A&M University. (May 2008) Emily Lynn Caulfield, B.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Eric Rothenbuhler This study explores how the unique history, culture, and traditions of Texas A&M University shape students’ perceptions and understandings of diversity and diversity programs. I examine these issues through participant observation of Texas A&M’s football traditions and in-depth, semi-structured interviews with members of the student body. In response to increased media scrutiny, public pressure, and scholastic competition, the current administration has embraced a number of aggressive initiatives to increase diversity among members of the student body. The collision between decades of tradition and the administration’s vision for the future has given rise to tension between members of the student body and the administration, which I argue is due, at least in part, to the culture that began developing at Texas A&M during the middle of the twentieth century as students began reacting to the prospect of change. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

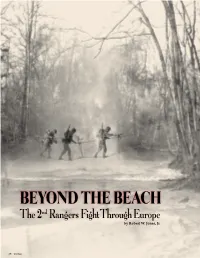

BEYOND THE BEACH The 2nd Rangers Fight Through Europe by Robert W. Jones, Jr. 16 Veritas nder the cover of a sunken road near a cemetery, two During World War II Camp Nathan Bedford companies of Rangers waited to begin the assault. U Forrest, located near Tullahoma, Tennessee, grew The bitter cold of the winter morning clung to them like from a small National Guard training site to one of a blanket. The Rangers faced a daunting task, assault the Army’s largest training bases. The camp was a across the open snow-covered field, protected by dug in major training area for infantry, artillery, engineer, German positions, and then climb the steep slopes of Hill and signal units. It also became a temporary camp for 400. The “Castle Hill” seemed impossible; several other troops during maneuvers, including Major General units had already tried and failed. It was 7 December George S. Patton’s 2nd Armored Division, “Hell 1944 and the 2nd Ranger Battalion, like the 5th Rangers, on Wheels,” and the Tennessee Maneuvers in 1944. had been fighting in Europe since 6 June 1944.1 Camp Forrest was also the birthplace of the 2nd and The exploits of the Rangers at Pointe du Hoc and 5th Ranger Battalions. Omaha Beach at Normandy are well known. Few people realize that the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions fought in Europe until May 1945 (“V-E Day”). While their combat units throughout the United States assembled there history began on D-Day, the two battalions fought to form the new unit. The well-publicized exploits of across France, in the Hürtgen Forest, and then through Lieutenant Colonel William O. -

Guy D. Whitten Texas A&M University Phone: (979) 845-2511 Department of Political Science Fax: (979) 847-8924 TAMUS 4348

Guy D. Whitten Texas A&M University Phone: (979) 845-2511 Department of Political Science Fax: (979) 847-8924 TAMUS 4348 Email: [email protected] College Station, TX 77843 Current Positions Cullen-McFadden Professor of Political Science, College of Liberal Arts, Texas A&M University. September 2018– Cornerstone Fellow, College of Liberal Arts, Texas A&M University. September 2015– Professor, Department of Political Science, Texas A&M University. September 2013– Director, European Union Center, Texas A&M University. April 2008– Previous Positions Cornerstone Fellow, College of Liberal Arts, Texas A&M University. September 2015–2018. Director, Program in Scientific Political Methodology, Texas A&M University. 2013-2017. Interim Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Texas A&M University. 2016-17. Visiting Professor, University of São Paulo, Brazil. 2013, 2014, 2015. Visiting Professor, Sciences-Po/LIEPP, Paris, Summer 2014. Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Texas A&M University. 2000-2013. Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Texas A&M University. 2008-11. Associate Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Texas A&M University. 2007-8. Interim Director, European Union Center, Texas A&M University. 2007-8. Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Texas A&M University. 1994-2000. Co-director, James Earl Rudder Normandy Program, Texas A&M University. Summer 1999. Visiting Researcher, Department of Political Science, University of Amsterdam. Spring 1998. Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, UCLA. 1993-4. Research Associate, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University. 1991-3. Research Assistant and Campaign Staff Member for John Cartwright, MP for Woolwich, UK, 1987. -

Texas Transportation Researcher

(;exos (;roltsportotiolt J(eseorelter PUBLISHED BY THE TEXAS TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE. TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY. COLLEGE STATION . TEXAS VOLUME 6 . NO.2 APRIL 1970 URBAN TRANSPORTATION PROBLEMS ARE APPRAISED AT A&M CONFERENCE Urban transportation problems and transportation in terms of establishing possible solutions were explored at the goals, objectives, and criteria; setting 12th annual Transportation Conference, standards for the allocation of re April 9-10, at Texas A&M University. sources; administering authority and Special attention was given to trans responsibility necessary for decision portation problems in the growing making; and regulating resource use. metropolitan areas of Texas. Carter, UMTA assistant administrator Carroll Carter of the U. S. Depart for public affairs, said public transpor ment of Transportation's Urban Mass tation has a new national priority, as Transportation Administration discussed evidenced by President Nixon's commit national plans and programs at the ment to a $10 billion, 12-year program opening-day luncheon. to build new transit systems with $3.1 The meeting, jointly sponsored by the billion available almost immediately. MacDonald Chair of Transportation and The federal official said the motoring public now understands that cities need the Texas Transportation Institute, at James Earl Rudder tracted industrial and governmental something more than highways and freeways-even if those improvements TEXAS AND THE NATION transportation representatives fro m MOURN THE LOSS OF throughout the nation. are buses and rapid transit systems that others would use. A&m PRESIDENT Program speakers included Texas Major General James Earl Rudder, A&M Engineering Dean Fred Benson, Speaking of "The City," Benson point President of the Texas A&M University discussing "The City;" TTI Director ed out that urban mass transportation System, died March 23 at the age of Charles J. -

Commission on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion's Report

STRONGER TOGETHER A Report by the Commission on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion January 2021 1 DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION TABLE OF CONTENTS Preamble Executive Summary I. Introduction IA. Commission Approach and Process IB. Defining a Land-Grant Institution II. Mission and Values IIA. Texas A&M University Guiding Statements IIB. Benchmark: Higher Education Guiding Statements IIC. Findings III. Campus Culture and Climate IIIA. Six Areas Affecting Campus Climate IIIB. Review: Barriers and Hindrances IIIC. Findings IIID.1. Attitudes toward Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) IIID.2. The Curricular Aggie Experience for Historically Marginalized Groups IIID.3. The Co-curricular Aggie Experience for Historically Marginalized Groups IV. Data and Policies IVA. Findings related to Undergraduate Students IVB. Findings related to Graduate and Professional Students IVC. Findings related to Faculty and Staff IVD. Findings related to Community and Vendors V. Voices from the Community (Community Engagement) VA. Community Voices Findings VA.1. Community Feedback: Identity Influences Opinion on DEI at TAMU VA.2. Community Feedback: DEI Efforts Must be Supported by Ongoing Engagement VA.3. Community Feedback: DEI Efforts Must be Tailored Toward Constituencies for Effective Engagement VA.4. Community Feedback: DEI Efforts Must be Fully Integrated Throughout Texas A&M and Require Additional Resources VA.5. Faculty Comments and Themes VA.6. Former Students Comments and Themes VA.7. Staff Comments and Themes VA.8. Current Students’ Comments and Themes VA.9. Greater Bryan/College Station Community Comments and Themes VB. Summary of Open Community Listening Sessions VI. Symbols, Namings and Iconography VIA. Purpose of Symbols, Naming and Iconography VIB. The Lawrence Sullivan Ross Statue at Texas A&M University VIC.