The Development of Liberal Arts Curricula at Fudan University, Shanghai Jiaotong University, and East China Normal University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shuang Zhang

June 2020 Shuang Zhang Department of Economics, University of Colorado Boulder Email: [email protected] Website: https://spot.colorado.edu/~shzh6533/index.html APPOINTMENTS 2020- Associate Professor of Economics (with tenure), University of Colorado Boulder 2013-2020 Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Colorado Boulder 2012-2013 SIEPR Postdoctoral Fellow, Stanford University AFFILIATIONS 2020- Faculty Research Fellow, National Bureau of Economic Research EDUCATION Ph.D. in Economics, Cornell University, 2012 M.A. in Economics, Fudan University, China, 2007 B.A. in Economics (with distinction), Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, China, 2004 RESEARCH INTERESTS Environment and Energy, Health, Development, China PUBLICATIONS “Willingness to Pay for Clean Air: Evidence from Air Purifier Markets in China” (with Koichiro Ito). Journal of Political Economy, 2020, 128 (5): 1627-1672. (Lead Article) “Land Reform and Sex Selection in China” (with Douglas Almond and Hongbin Li). Journal of Political Economy, 2019, 127 (2): 560-585. “The Limits of Political Meritocracy: Screening Bureaucrats Under Imperfect Verifiability” (with Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato and Xiao Yu Wang). Journal of Development Economics, 2019, 140: 223-241. “Quantifying Coal Power Plant Responses to Tighter SO2 Emissions Standards in China” (with Va- lerie Karplus and Douglas Almond). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018, 115 (27): 7004-7009. “The Effects of High School Closure on Education and Labor Market Outcomes in Rural China”. Economic Development and Culture Change, 2018, 67 (1): 171-191. 1 WORKING PAPERS Reforming Inefficient Energy Pricing: Evidence from China (with Koichiro Ito), NBER WP 26853, 2020. Ambiguous Pollution Response to COVID-19 in China (with Douglas Almond and Xinming Du), NBER WP 27086, 2020. -

2019 Year Book.Pdf

2019 Contents Preface / P_05> Overview / P_07> SICA Profile / P_15> Cultural Performances and Exhibitions, 2019 / P_19> Foreign Exchange, 2019 / P_45> Academic Conferences, 2019 / P_67> Summary of Cultural Exchanges and Visits, 2019 / P_77> 「Offerings at the First Day of Year」(detail) by YANG Zhengxin Sea Breeze: Exhibition of Shanghai-Style Calligraphy and Painting Preface This year marks the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Over the past 70 years, the Chinese culture has forged ahead regardless of trials and hardships. In the course of its inheritance and development, the Chinese culture has stepped onto the world stage and found her way under spotlight. The SICA, established in the golden age of reform and opening-up, has been adhering to its mission of “strengthening mutual understanding and friendly cooperation between Shanghai and other countries or regions through international cultural exchanges in various areas, so as to promote the economic development, scientific progress and cultural prosperity of the city” for more than 30 years. It has been exploring new modes of international exchange and has been actively engaging in a variety of international culture exchanges on different levels in broad fields. On behalf of the entire staff of the SICA, I hereby would like to extend our sincere gratitude for the concern and support offered by various levels of government departments, Council members of the SICA, partner agencies and cultural institutions, people from all circles of life, and friends from both home and abroad. To sum up our work in the year 2019, we share in this booklet a collection of illustrated reports on the programs in which we have been involved in the past year. -

A Large-Scale Clinical Validation Study Using Ncapp Cloud Plus

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.07.20163402; this version posted August 11, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . A Large-Scale Clinical Validation Study Using nCapp Cloud Plus Terminal by Frontline Doctors for the Rapid Diagnosis of COVID-19 and COVID-19 pneumonia in China Dawei Yang, M.D.1,20,25#, Tao Xu, M.D.2,18#, Xun Wang, M.D.3,21#, Deng Chen, M.S.4#, Ziqiang Zhang, M.D.5#, Lichuan Zhang, M.D.6#, Jie Liu, M.D.1,25, Kui Xiao, M.D.7, Li Bai, M.D.8, Yong Zhang, M.D.1,25, Lin Zhao, M.D.9, Lin Tong, M.D.1, Chaomin Wu, M.D.10,23, Yaoli Wang, M.D.12, Chunling Dong, M.D.12, Maosong Ye, M.D.1,25, Yu Xu, M.D.,8,24, Zhenju Song, M.D.13, Hong Chen, M.D.14, Jing Li1,25, Jiwei Wang, Ph.D.4, Fei Tan, M.S.15, Hai Yu, M.S.15, Jian Zhou, Ph.D.1,25, Jinming Yu, Ph.D.4, Chunhua Du, M.D.2, Hongqing Zhao, M.D.3, Yu Shang, M.D.16, Linian Huang17, Jianping Zhao, M.D.18, Yang Jin, M.D.19, Charles A. Powell, M.D.20, Yuanlin Song, M.D.1,25*, Chunxue Bai, M.D.1,25* 1. -

A Legacy in Chinese Education History, Or a Solution for Modern Undergraduates in China?

Journal of Education and Learning; Vol. 9, No. 6; 2020 ISSN 1927-5250 E-ISSN 1927-5269 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Chinese Shuyuan: A Legacy in Chinese Education History, or a Solution for Modern Undergraduates in China? Zhen Zeng1 1 School of Foreign Studies, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, Guangxi, China Correspondence: Zhen Zeng, 82 Liuhe Road, Qixing District, Guilin, Guangxi, Postal Code: 541004, China. E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 28, 2020 Accepted: November 19, 2020 Online Published: November 26, 2020 doi:10.5539/jel.v9n6p173 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v9n6p173 Abstract The paper looked into concepts claimed to be essence of Chinese residential college, an on-going institution presumed to be a solution towards undergraduates’ issues in some pioneer universities in China. It’s analyzed that Chinese residential college today in China is not a Shuyuan that was ever striving as a unique education mode in ancient China, even if it’s named after Shuyuan in Chinese, concerning on its nature, function and goal, while it’s not a conventional residential college in English speaking countries neither. By investigation and comparison of its origin, function and features among Shuyuan and Chinese residential college, the spirit of development of a human with goodness and well-being through pursuit of knowledge and culture inherited and transmitted in Shuyuan is unearthed, which is supposed to be the resource of inspiration when the pioneer universities and educators designed and operate residential college on Chinese campus, though the effects couldn’t be accounted as appealing as what Shuyuan produced in ancient China. -

Ninghua, ZHONG (钟宁桦)

Ninghua, ZHONG (钟宁桦) Professor, Economics and Finance School of Economics and Management Tongji University, Shanghai [email protected]; [email protected] Academic Background PhD in Finance, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, January 2013 PhD Committee: Sudipto Dasgupta, Vidan K. Goyal, K. C. John Wei, Albert Park, Zhigang Tao MA in Economics, Peking University, China Center for Economic Research, July 2008 Adviser: Yang Yao BA in Economics with highest distinction, Fudan University, School of Economics, July 2005 GPA: 3.82 out of 4.00 Class rank: 1 out of 109 Current Academic Appointment Professor, School of Economics and Management, Tongji University Promoted to Full Professor in December 2015 due to my exceptional performance Promoted to Associate Professor in June 2013 shortly after joining the university in March 2013 Teaches at one of the premier Executive MBA programs in the world (Tongji University/ENPC), ranked 68th in 2014 by the Financial Times Research interests include (a) applied microeconomics studies in the fields of labor economics, corporate finance, and empirical asset pricing and (b) Chinese economic reform and development Ningua, ZHONG (钟宁桦) 1 Publications and Working Papers—English As of December 2015, Google Scholar calculated 225 citations of my papers: On China’s Labor Market Issues (Papers in this field are developed from my master thesis) “Unions and Workers’ Welfare in Chinese Firms” (with Yang Yao), [download from JSTOR] Journal of Labor Economics 31, no. 3 (2013): 633–67. -

EMA Program in Chinese Philosophy and Culture

EMA Program in Chinese Philosophy and Culture I. Academic Programs Overview These programs are aimed to offer opportunities of learning Chinese and studying Chinese philosophy to overseas postgraduates or college juniors and seniors who have not yet been able to master the Chinese language. In addition to Chinese language classes, these programs offer courses on Chinese philosophy as well as other related courses in English at Fudan University. Fudan University is a leading institution of higher education in China, and is experienced with and renowned for educating overseas students. The School of Philosophy at Fudan is a top philosophy program in China. The university is located in Shanghai, the most dynamic city in China that belongs to a region that is rich in Chinese traditions and cultures. It has been 10 years since these programs were launched in 2011, and 105 students have been enrolled in either the M.A. program (87 students) and the visiting student program (18 students). They are from 35 countries (the U.S., Canada, Puerto Rico, Barbados, Uruguay, Brazil, Chile, Australia, the U.K., Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Montenegro, Slovenia, Russia, Israel, Turkey, Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, India, Bangladesh, and Gambia, with student from North America and Europe forming the majority of the student body), and many of them are top students in their classes, majoring in philosophy, classics, and/or East Asian or Chinese studies. The above facts make these programs simply the most successful of their kind (English-based post-graduate programs in Chinese philosophy) in mainland China. -

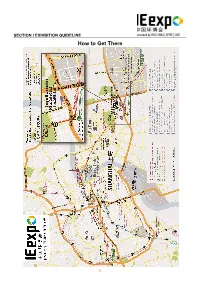

How to Get There

SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There 12 SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There (cont’d) Shanghai Metro Map 13 SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There (cont’d) SNIEC is strategically located in Pudong‘s key economic development zone. There is a public traffic interchange for bus and metro, , one named “Longyang Road Station“ about 10-min walk from the station to fairground, and one named “Huamu Road Station“ about 1-min walk from the station to fairground. By flight The expo centre is located half way between Pudong International Airport and Hongqiao Airport, 35 km away from Pudong International Airport to the east, and 32 km away from Hongqiao Airport to the west. You can take the airport bus, maglev or metro directly to the expo center. From Pudong International Airport By taxi By Transrapid Maglev: from Pudong International Airport to Longyang Road Take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station to change line 7 to Huamu Road Station, 60 min. By Airport Line Bus No. 3: from Pudong Int’l Airport to Longyang Road, 40 min, ca. RMB 20. From Hongqiao Airport By taxi Take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station to change line 7 to Huamu Road Station, 60 min. By train From Shanghai Railway Station or Shanghai South Railway Station please take metro line1 to People’s Square, then take metro line 2 toward Pudong International Airport Station and get off at Longyang Road Station to change line7 to Huamu Road Station. From Hongqiao Railway Station, please take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station and change line 7 to Huamu Road Station. -

FPCP 2021 Fudan University, Shanghai

FPCP 2021 Fudan University, Shanghai Chengping Shen Fudan University [email protected] When and where? Date: June in 2021 Method: in person (hope the COVID-19 could disappear soon) or hybrid of in person plus online Location: on Campus of Fudan University. Conference web site (with visa information) and poster will be released by the end of next month. Indico web page will be announced by the end of this year Fudan University Located in Shanghai, ~ 1 hour typical driving time from Pudong international Airport, 40 minutes typical driving time from Hongqiao international Airport and Hongqiao High speed train station; ~2 hours and 25 minutes flight from shanghai to Beijing Capital International Airport, 4 ~ 5 hours for high speed train Very convenient traffic. (10 minute walk to subway station) Flight to Shanghai Transport to Fudan Univ. Wujiao Square 20 CNY Fudan 20 CNY University Subway Subway station 40 CNY Pudong Airport shuttle No.4 Taxi Shanghai Line No.3 Railway Station Chifeng Rd. Maglev 150 CNY Train Shiji Ave. Baoshan Rd. 100 CNY 120 CNY Line No.2 Longyang Rd. Line No.3 Line No.10 Hongqiao Airport Railway station Pudong Airport Shanghai south railway station Introduction to Fudan and our lab Fudan University Established in 1905 Number of Undergraduate (13,136) and Graduate (20,309) Number of Faculty (6,002) QS World University Ranking 2020: Rank number: 40 Fudan is one of the top universities in China Key Lab of Nuclear Physics and Ion-beam Application (MOE). Research Directions: (1) High Energy Nuclear and Particle Physics (2) Highly Charged Ion Physics (3) Nuclear Technology and Radiation (4) Nuclear Bio-medical Physics and Radio-therapy Landscape on campus Conference Venue: Guanghua Building in Fudan Univ. -

Curriculum Vitae Jianfeng Wu

Curriculum Vitae Jianfeng Wu School of Economics, Fudan University 600 Guoquan Road, 200433, Shanghai, P.R.China Tel: (86)-021-6564 2076 | Email: [email protected] Ph.D. | Urban and Regional Economics, 2009 National University of Singapore, Singapore M. Econ. | Regional Economics, 2003 Peking University, Beijing, China B.Econ. | Real Estate Economics, 2000 East China Normal University, Shanghai, China CURRENT ACADEMIC POSITION Assistant Professor, School of Economics, Fudan University, Shanghai AREAS OF RESEARCH w Urban and Regional Economics w Real Estate Economics AREAS OF TEACHING w Urban Economics and Real Estate Market (Master Programs) w Theories of Urban Economics (Undergraduate programs) w Intermediate Microeconomics (Undergraduate programs) EMPLOYMENT EXPERIENCE w School of Economics, Fudan University Assistant Professor, 2009- w Department of Real Estate, National University of Singapore Lecturer, Aug 2007-Dec 2007 Research Assistant, Jan 2005- Dec 2005 HONORS AND AWARDS w Full Ph.D Scholarship, 2003-2008, National University of Singapore w Scholarship of Korea Studies, 2001, Korea Foundation and Peking University RESEARCH ACTIVITIES Ph.D. Thesis Wu, J., “The spatial aspects of recent economic development in China”, the PhD thesis, National University of Singapore (NUS), 2009. Research Projects Wu.J.,”The Spatial Evolution of Industrial Activities in China”, National Natural Science Foundation of China (71003026) Published Paper Wu,J. and Zhou W.,”The Evolution of China’s Urbanization: Facts, Driving Forces and Policy Suggestions”, Urban Studies (CHENGSHIFAZHANYANJIU in Chinese), 5, 2011,21-26. Wu,J., and Fu,Y.,” The co-evolution of spatial agglomeration and firm size in China’s manufacturing industries”, China Economic Quarterly (JINGJIXUE JIKAN in Chinese), 11(2),675- 690. -

Universities and the Chinese Defense Technology Workforce

December 2020 Universities and the Chinese Defense Technology Workforce CSET Issue Brief AUTHORS Ryan Fedasiuk Emily Weinstein Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 5 Methodology and Scope ..................................................................................... 6 Part I: China’s Defense Companies Recruit from Civilian Universities ............... 9 Part II: Some U.S. Tech Companies Indirectly Support China’s Defense Industry ................................................................................................................ 13 Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 17 Acknowledgments .............................................................................................. 18 Appendix I: Chinese Universities Included in This Report ............................... 19 Appendix II: Breakdown by Employer ............................................................. 20 Endnotes .............................................................................................................. 28 Center for Security and Emerging Technology | 2 Executive Summary Since the mid-2010s, U.S. lawmakers have voiced a broad range of concerns about academic collaboration with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), but the most prominent -

Call for Papers Special Issue on New Advances of Privacy Protection and Multimedia Content Security for Big Data for IETE TECHNICAL REVIEW

Call for Papers Special Issue on New Advances of Privacy Protection and Multimedia Content Security for Big Data for IETE TECHNICAL REVIEW Aims and Scope Multimedia signal processing and Internet technology are omnipresent in our daily lives, however, a lot of relevant security issues have emerged as well, such as covert communication using multimedia files, copy-move forgery in digital images and videos, biometric spoofing. To address these issues, many multimedia information security techniques were proposed utilizing the methods in areas like deep learning, signal and image processing in encrypted domain, and privacy protection. Nevertheless, there are some notable shortcomings in research methodologies. Current studies for the multimedia content security are often based on the strict conditions that are nearly impossible to meet up in real world. Furthermore, the high computational complexity of the current methods makes it hard to handle the big data in the cloud computing environment. All these drawbacks limit the applications of the secure techniques in practice. This special issue will focus on the latest research on the topics of privacy protection and multimedia information security, with a particular emphasis on novel and highly efficient methodologies that have the potential to be used for big data. Possible topics for the manuscripts submitted to this special issue include, but are not limited to: Multimedia Fingerprinting and Traitor Tracing Multimedia Watermarking, Fingerprinting and Identification Multimedia Forensic, Authentication and Encryption Multimedia Privacy Protection for Big Data Steganography and Steganalysis for Big Data Signal Processing in the Encrypted Domain Coverless Information Hiding Biometrics Encryption and Hashing in cloud storages Source Device Identification and Linking Security of Large Multimedia System Covert Communications and Surveillance. -

Shanghai Stories: 30Th Anniversary of the U.S

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Shanghai Stories: 30th Anniversary of the U.S. Consulate in Shanghai Beatrice Camp, Editor Copyright 2013 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Don Anderson, Consul eneral 1980-1983 Consulate eneral&s 'Happy Hour( David Hess, Branch PAO 1980-19?? ,S failed effort to rescue Teheran embassy hostages spar.s anti-,.S. demonstration Thomas Biddic., Consular, later Political Officer 1980-1980 Opening Consulate in1980. Housing and environment Dengist reforms Ohel 1achel Synagogue President Clinton visit 2rs. Clinton&s speech Steve Schlai.jer, Consular Officer 1980-1980 China&s soccer team victory over 3uwait spar.s vast demonstrations, which threatened to become ugly. Tom 5auer 1980-1980? The sight of blond-haired Americans ama6es Chinese Tess 7ohnston 1981-1988 Housing, restrictions and general environment Stan Broo.s, Consul eneral 1983-1987 President 1eagan spea.s at Fudan ,niversity America as Disneyland Post and personnel awards CODE5s and other visitors eneral post activities Shanghai American School Photos Demonstrations 1 3ent Wiedemann 1983-1988 President 1eagan visit 5loyd Neighbors, Branch Public Affairs Officer 1983-1988 5iving conditions and environment Climate Changes for the better 2rs. Du 2uriel Hoopes 2r. Wang Earlier prohibition of cultural events English language 2usic lecture Delegation of American Writers Ira 3asoff, Commercial Officer 1985-1987 Sunday afternoon football games 0004-0007 Shanghai Consulate Chamber of Conference 3eith Powell, Consular Section Chief 1985-1987 Consular 'Elf( '2illion degree( Bar-B-Que 7oint ,SAAussie T IFs American School regorie W. Bujac, Diplomatic Security Officer 1988-1987 Finding a site for the Consulate eneral Charles Sylvester, Consul eneral 1987-1989 Former Consuls Fran.