Diet and Prey Availability of Sturgeons in the Penobscot River, Maine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.Xml

G:\COMP\PARKS\WILD AND SCENIC RIVERS ACT.XML WILD AND SCENIC RIVERS ACT [Public Law 90–542; Approved October 2, 1968] [As Amended Through P.L. 116–9, Enacted March 12, 2019] øCurrency: This publication is a compilation of the text of Public Law 90–542. It was last amended by the public law listed in the As Amended Through note above and below at the bottom of each page of the pdf version and reflects current law through the date of the enactment of the public law listed at https:// www.govinfo.gov/app/collection/comps/¿ øNote: While this publication does not represent an official version of any Federal statute, substantial efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of its contents. The official version of Federal law is found in the United States Statutes at Large and in the United States Code. The legal effect to be given to the Statutes at Large and the United States Code is established by statute (1 U.S.C. 112, 204).¿ AN ACT To provide a National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That ø16 U.S.C. 1271¿ (a) this Act may be cited as the ‘‘Wild and Scenic Rivers Act’’. (b) It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States that certain selected rivers of the Nation which, with their imme- diate environments, possess outstandingly remarkable scenic rec- reational, geologic fish and wildlife, historic, cultural or other simi- lar values, shall be preserved in free-flowing condition, and that they and their immediate environments shall be protected for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations. -

109167-Moxiebro-12-Sc.Pdf

e MAINE WILDERNESS OVERNIGHTS AND SUPER TRIPS O Overnight river trips are a wonderful way to explore the wild rivers of Maine. Two days of paddling and camping on the river. We start our adventure inflatable kayaking with rapids up to Class III. Your guides with give you pointers along the way, and before you know it you will be searching out waves to run and holes to surf. We stop for a lunch and a hike to one of the area waterfalls or swimming holes, and then we switch to our historic 10 person voyageur canoes to paddle to a remote camping site along the Kennebec River and Wyman Lake. Our riverside camp is set up so you can just relax, and enjoy the scenery, while your guides are preparing dinner. The stars at night are just spectacular from camp. Day two we raft on the exciting Class IV and V rapids of the Kennebec River Gorge. A steak/chicken barbecue is served riverside before we return to Lake Moxie Base Camp. This trip OutdoorOutdoor is all-inclusive: river and camping gear, shuttles and hearty meals optional Maine Lobster bake. Minimum group size required. Our Maine Super Trip is based out of Lake Moxie Camps in platform tents and includes all of the above plus a floatplane AdventuresAdventures Moose Safari! Cabin upgrades available. LOwer KennebeC infLatabLe KayaK “funyaKs” yageur Can yageur This very scenic 7-mile section of river with swift moving water up to class II is perfect for Funyaking. The rapids are easy and fun and the scenery is beautiful. -

Diet and Prey Availability of Sturgeons in the Penobscot River, Maine Matthew Dzaugis University of Maine - Main

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Maine The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2013 Diet and Prey Availability of Sturgeons in the Penobscot River, Maine Matthew Dzaugis University of Maine - Main Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Biology Commons, Marine Biology Commons, Population Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Dzaugis, Matthew, "Diet and Prey Availability of Sturgeons in the Penobscot River, Maine" (2013). Honors College. 106. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/106 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIET AND PREY AVAILABILITY OF STURGEONS IN THE PENOBSCOT RIVER, MAINE by Matthew P. Dzaugis A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Marine Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2013 Advisory Committee: Dr. Gayle B. Zydlewski, Research Associate Professor, Advisor Dr. Michael T. Kinnison, Professor Dr. Mimi Killinger, Rezendes Preceptor for the Arts Dr. Sara Lindsay, Associate Professor Matthew Altenritter, Ph.D. candidate Copyright 2013 Matthew P. Dzaugis Abstract Although vital to the protection and conservation of species listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, critical habitat of shortnose sturgeon and Atlantic sturgeon in the Penobscot River, Maine have not yet been described. -

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13Th) Edition

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13th) Edition T OF EN CO M M T M R E A R P C E E D U N A I C T I E R D E S M T A ATES OF U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RDML Timothy Gallaudet., Ph.D., USN Ret., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere National Ocean Service Nicole R. LeBoeuf, Deputy Assistant Administrator for Ocean Services and Coastal Zone Management Cover image courtesy of Megan Greenaway—Great Salt Pond, Block Island, RI III Preface Distances Between United States Ports is published by the Office of Coast Survey, National Ocean Service (NOS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), pursuant to the Act of 6 August 1947 (33 U.S.C. 883a and b), and the Act of 22 October 1968 (44 U.S.C. 1310). Distances Between United States Ports contains distances from a port of the United States to other ports in the United States, and from a port in the Great Lakes in the United States to Canadian ports in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. Distances Between Ports, Publication 151, is published by National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and distributed by NOS. NGA Pub. 151 is international in scope and lists distances from foreign port to foreign port and from foreign port to major U.S. ports. The two publications, Distances Between United States Ports and Distances Between Ports, complement each other. -

Salmon River Management Plan, Idaho

Bitterroot, Boise, Nez Perce, Payette, and Salmon-Challis National Forests Record of Decision Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Frank Church – River of No Return Wilderness Revised Wilderness Management Plan and Amendments for Land and Resource Management Plans Bitterroot, Boise, Nez Perce, Payette, and Salmon-Challis NFs Located In: Custer, Idaho, Lemhi, and Valley Counties, Idaho Responsible Agency: USDA - Forest Service Responsible David T. Bull, Forest Supervisor, Bitterroot NF Officials: Bruce E. Bernhardt, Forest Supervisor, Nez Perce NF Mark J. Madrid, Forest Supervisor, Payette NF Lesley W. Thompson, Acting Forest Supervisor, Salmon- Challis NF The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital and family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Person with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Ave., SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. ROD--II Table of Contents PREFACE ............................................................................................................................................... -

Maineâ•Žs Youth Fishing Waters

Maine State Library Digital Maine Public Information and Education Documents Inland Fisheries and Wildlife 3-26-2012 Maine’s Youth Fishing Waters Maine Division of Public Information and Education Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/pie_docs Recommended Citation Maine Division of Public Information and Education and Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, "Maine’s Youth Fishing Waters" (2012). Public Information and Education Documents. 1. https://digitalmaine.com/pie_docs/1 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Information and Education Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maine’s Youth Fishing Waters Androscoggin County Penobscot County Pettingill Park Pond, Auburn Cold Stream* (portion of), Enfield Giles Pond, Patten Aroostook County Jerry Pond, Millinocket Aroostook River* (portion of) Johnny Mack Brook, Orono Hannington Pond, Reed Plantation Little Round Pond (December 1 through April Mantle Lake, Presque Isle 30), Lincoln Pearce Brook (portion of), Houlton Mattagodus Stream* (portion of), Springfield Rock Crusher Pond Mill Stream (outlet of Little Wassookeag Lake), Dexter Cumberland County Rocky Brook, Lincoln Aldens Pond, Gorham Coffin Pond, Brunswick Piscataquis County Lower Hinckley Pond, South Portland Drummond Pond, Abbott (ice fishing only) Stevens -

Bikemaine 2016

2016 FINISHMachias Discover the Bold Coast! LUNCH Machiasport Fire Station DAY 2 Sept. 12 54 miles 2,852 ft elevation gain start Jonesport REST rest stop #1 (12.5 mi) STOP #1 Jonesport Town Park Jonesport Town Park lunch stop (39.5 mi) Machiasport START Fire Station & Jonesport Town Complex finish Machias route SAG Support 207-200-7845 color YELLOW CUE SHEET Day 2 | Sept. 12 | 54 miles | 2,852 ft elevation gain Leg Total Directions Leg Total Directions 0 Depart BikeMaine Village on Albert Kelley Road 0 30.3 Make U-turn at boat launch 1.3 0.1 Turn left onto Kelley Point Road 1.8 30.3 Exit park on Schoppee Point Rd./Becomes Roque Bluffs Rd. 1.5 1.4 Turn left onto ME-187 3.5 32.1 Stay straight onto Roque Bluffs Rd. 0.5 2.9 Turn left onto Bridge St.; cross bridge to Beals Island 0.1 35.6 Turn right onto West Kennebec Rd. 1.2 3.4 Immediately after bridge turn left onto Barney's Cove Rd./Bayview Drive 0.9 35.7 Turn left onto Cross Rd. 0 4.6 Continue onto Bay View Dr.; cross bridge onto Great Wass Island 2.4 36.6 Turn right onto East Kennebec Rd. 0.9 4.6 Turn left onto Alleys Bay Rd. 0.5 39 Turn right onto Port Rd./Rte 92 0.1 5.5 Make U turn at Town Landing 0 39.5 Turn right into Machiasport Fire Station/Town Complex - Lunch Stop 0.9 5.6 Turn right onto Alleys Bay Rd. -

Sprague's Journal of Maine History

Class J- / rn Bonk , Fb 76 -I Sprague's Journal of Maine History VOL. Ill APRIL 1915-APRIL 1916 10HN FRANCIS SPRAGUE EDITOR AND PUBLISHER WM. W. ROBERTS CO. Stationers and Blank. Book. Manufacturers Office Supplies, Filing Cabinets and Card Indexes 233 Middle Street, PORTLAND, MAINE The Royal Standard Typewriter PUBLIC AUTO The Established Leader Tire Repairing and Vulcanizing All kinds of Typewriters bought, sold, Satisfaction Guaranteed exchanged and repaired. LESLIE E. JONES FRED W. PALMER 130 Main St., BANGOR, MAINE DOVER, MAINE Send Your Linen by Parcel Post to Guilford steam Laundry V. H. ELLIS, Prop., GUILFORD, MAINE We Pay Return Postage E) A VC I C^ Ayr Lay your plans to start your savings account I 1 ' HIO I II <^ H I L with this bank on your very next pay-day. Set aside One Dollar—more if you can spare it come to the urt nk and make your first deposit. Small sums are welcomed. Put system into your sav inu's. Save a little every week and save that little regularly. Make it an obligation to yourself just as you are duty bound to pay the grocer orthe coal mm. SAVE FAITHFULLY. The dollars you save now will serve you later on when you will have greater need for them. PISCATAQUIS SAVINGS BANK, Dover, Maine. F. E. GUERNSEY, Pre s. W. C. WOODBURY, Treas. Monej Back If Not Satisfied Bangor & Aroostook Is Your Protection RAILROAD JOHN T. CLARK & Co. DIRECT ROUTE to Greenville, Fort CLOTHIERS Kent, Houlton, Presque Isle, Cari- BANGOU, MAINE bou, Fort Fairfield, Van Buren and Northern Maine. -

High Value Plant & Animal Habitats

N T O 1 8 R T E H D F B I E P L P D An Approach to Conserving Maine's Natural Descriptions of Labeled High Value Plant and Animal Habitats LEGEND Space for Plants, Animals, and People The data presented here represent the best available information provided through k o t Beginning with Habitat coalition partners at the time of map drafting. Map users should o t No. Feature Name Status No. Feature Name Status r o c consult with the Beginning with Habitat program to verify that data illustrated on this map B www..begiinniingwiitthhabiittatt..org S Berry 1 Raised Level Bog Ecosystem is still current prior to utilizing it for planning decisions. Habitat features illustrated on this t Heath n a map are based on limited field surveys, aerial photo interpretation, and computer y COLOR CODES: Primr ary Map 2 192 modeling. Many areas have not been completely surveyed, so it is possible that features B Rare Plant Rare or Exemplary Natural Community may be present that are not mapped. Habitat data sets are updated continuously. Not Rare Animal Location/Habitat Essential Habitat all habitats described below may occur in the area shown in this map. Also, please note High Value Plant & Animal Habitats STATE STATUS: that some of these habitats are regulated by the State of Maine through the Maine ELD E = Endangered PE = Possibly Extirpated E(B) = Endangered Breeding Population HFI Endangered Species Act (Essential Habitats and threatened and endangered species RT ELD T = Threatened SC = Special Concern occurrences) and Natural Resource Protection Act (Significant Wildlife Habitat). -

Final DCC Trail Map & Guide 27X24

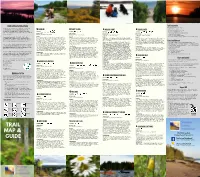

Klondike Mountain, Lubec Machias River Preserve, Machias Pigeon Hill, Steuben Middle River Park, Machias Mowry Beach, Lubec Pike Lands Preserve, Lubec Downeast Coastal Conservancy Land Conservation DCC conserves land that preserves: The Downeast Coastal Conservancy (DCC) maintains and PIGEON HILL TIBBETT ISLAND Public access to natural areas conserves fifteen public access preserves and works INGERSOLL POINT TIDE MILL CREEK Recreational and cultural resources cooperatively with landowners to conserve other land in Trail Activity: Trail Activity: Trail Activity: Trail Activity: Scenic views and landscapes coastal Washington County from Steuben to Lubec and up to Biological diversity and ecological corridors Difficulty & Length: Calais and Route 9. Difficulty & Length: Difficulty & Length: Difficulty & Length: Land and water resources Moderate, 1.8 miles of trail network Moderate, 1.0 mile of trail network Moderate, 3.4 miles of trail network Moderate, 2.0 miles of trail network Climate change mitigation projects These preserves are part of the last frontier on the Description: Description: Description: Description: Productive working landscapes (includes forestry, farming, fishing) Pigeon Hill is the highest coastal property in Washington County Northeast coast of peaceful, untrammeled beauty; they Tibbett is a 23-acre island about 600 feet offshore from The Ingersoll Point Preserve consists of 145-forested acres with The property includes more than two miles of gentle trails open to with a summit elevation of 317 ft. The 1.8 mile trail system on the Mooseneck at the southern tip of Addison. The island has nearly a over one mile of rocky shoreline on Carrying Place Cove and Wohoa hiking, snowshoeing and cross-country skiing. -

Water Chemistry of the Narraguagus River: a Summary of Available Data from the Maine DEP Salmon Rivers Program

Spatial and Temporal Patterns in Water Chemistry of the Narraguagus River: A Summary of Available Data from the Maine DEP Salmon Rivers Program By Mark Whiting, Maine Department of Environmental Protection and William Otto, University of Maine at Machias In collaboration with the Narraguagus River Watershed Council and Downeast Salmon Federation November 18, 2008 DEPLW-0940 I. Introduction: Background: The Narraguagus River is one of eight Maine rivers within the Gulf of Maine Distinct Population Segment with endangered Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). In 1999, a volunteer-based water quality monitoring program was established to evaluate water quality in these rivers. This program is managed by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), which works cooperatively with local grass-roots watershed councils. The results of these studies have been previously published as progress reports. The river-specific reports available so far, include the Sheepscot River (Whiting 2006a), Kenduskeag Stream (Whiting 2006b) and the Ducktrap River (Whiting 2007a). No river-specific summaries exist for the downeast rivers (i.e., the Washington County salmon rivers, namely the Narraguagus, Pleasant, Machias, East Machias, and Dennys Rivers). However, more general overviews of all the Maine salmon rivers do exist (Whiting 2001, 2002, 2003). The purpose of this study is to evaluate present water quality in the Narraguagus River, provide a baseline for the detection of trends, and present a single river summary for this river. Particular attention was devoted to three different water quality issues, namely acid rain effects, the potential for bacterial contamination in downtown Cherryfield, and an evaluation to see if this river meets its state water quality classification standards. -

533 Part 117—Drawbridge Operation

Coast Guard, DHS Pt. 117 nor relieve any bridge owner of any li- 117.115 Three Mile Creek. ability or penalty under other provi- ARKANSAS sions of that act. 117.121 Arkansas River. [CGD 91–063, 60 FR 20902, Apr. 28, 1995, as 117.123 Arkansas Waterway-Automated amended by CGD 96–026, 61 FR 33663, June 28, Railroad Bridges. 1996; CGD 97–023, 62 FR 33363, June 19, 1997; 117.125 Black River. USCG–2008–0179, 73 FR 35013, June 19, 2008; 117.127 Current River. USCG–2010–0351, 75 FR 36283, June 25, 2010] 117.129 Little Red River. 117.131 Little River. PART 117—DRAWBRIDGE 117.133 Ouachita River. 117.135 Red River. OPERATION REGULATIONS 117.137 St. Francis River. 117.139 White River. Subpart A—General Requirements CALIFORNIA Sec. 117.1 Purpose. 117.140 General. 117.4 Definitions. 117.141 American River. 117.5 When the drawbridge must open. 117.143 Bishop Cut. 117.7 General requirements of drawbridge 117.147 Cerritos Channel. owners. 117.149 China Basin, Mission Creek. 117.8 Permanent changes to drawbridge op- 117.150 Connection Slough. eration. 117.151 Cordelia Slough (A tributary of 117.9 Delaying opening of a draw. Suisun Bay). 117.11 Unnecessary opening of the draw. 117.153 Corte Madera Creek. 117.15 Signals. 117.155 Eureka Slough. 117.17 Signalling for contiguous draw- 117.157 Georgiana Slough. bridges. 117.159 Grant Line Canal. 117.19 Signalling when two or more vessels 117.161 Honker Cut. are approaching a drawbridge. 117.163 Islais Creek (Channel). 117.21 Signalling for an opened drawbridge.