New Pieces of the Trichinella Puzzle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gastrointestinal Helminthic Parasites of Habituated Wild Chimpanzees

Aus dem Institut für Parasitologie und Tropenveterinärmedizin des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Gastrointestinal helminthic parasites of habituated wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in the Taï NP, Côte d’Ivoire − including characterization of cultured helminth developmental stages using genetic markers Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Veterinärmedizin an der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Sonja Metzger Tierärztin aus München Berlin 2014 Journal-Nr.: 3727 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jürgen Zentek Erster Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Georg von Samson-Himmelstjerna Zweiter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Heribert Hofer Dritter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Achim Gruber Deskriptoren (nach CAB-Thesaurus): chimpanzees, helminths, host parasite relationships, fecal examination, characterization, developmental stages, ribosomal RNA, mitochondrial DNA Tag der Promotion: 10.06.2015 Contents I INTRODUCTION ---------------------------------------------------- 1- 4 I.1 Background 1- 3 I.2 Study objectives 4 II LITERATURE OVERVIEW --------------------------------------- 5- 37 II.1 Taï National Park 5- 7 II.1.1 Location and climate 5- 6 II.1.2 Vegetation and fauna 6 II.1.3 Human pressure and impact on the park 7 II.2 Chimpanzees 7- 12 II.2.1 Status 7 II.2.2 Group sizes and composition 7- 9 II.2.3 Territories and ranging behavior 9 II.2.4 Diet and hunting behavior 9- 10 II.2.5 Contact with humans 10 II.2.6 -

This Is an Open Access Document Downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's Institutional Repository

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/117055/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Jorge, F., White, R.S.A. and Paterson, Rachel A. 2018. Hiding in the swamp: new capillariid nematode parasitizing New Zealand brown mudfish. Journal of Helminthology 92 (3) , pp. 379-386. 10.1017/S0022149X17000530 file Publishers page: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X17000530 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X17000530> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. Title: Hiding in the swamp: new capillariid nematode parasitizing New Zealand brown mudfish Authors: Fátima Jorge1, Richard S. A. White2 and Rachel A. Paterson1,3 Addresses: 1Department of Zoology, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand; 2School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand; 3School of Biosciences, University of Cardiff, Cardiff, CF10 3AX, United Kingdom Running headline: Capillariid nematode parasitizing New Zealand mudfish Corresponding author: Fátima Jorge Department of Zoology, University of Otago, 340 Great King Street, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] 1 Abstract The extent of New Zealand’s freshwater fish-parasite diversity has yet to be fully revealed, with host-parasite relationships still to be described from nearly half the known fish community. -

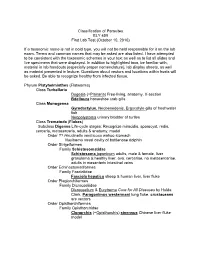

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

Tissue Nematode: Trichenella Spiralis

Tissue nematode: Trichenella spiralis Introduction Trichinella spiralis is a viviparous nematode parasite, occurring in pigs, rodents, bears, hyenas and humans, and is liable for the disease trichinosis. It is occasionally referred to as the "pork worm" as it is characteristically encountered in undercooked pork foodstuffs. It should not be perplexed with the distantly related pork tapeworm. Trichinella species, the small nematode parasite of individuals, have an abnormal lifecycle, and are one of the most extensive and clinically significant parasites in the whole world. The adult worms attain maturity in the small intestine of a definitive host, such as pig. Each adult female gives rise to batches of live larvae, which bore across the intestinal wall, enter the blood stream (to feed on it) and lymphatic system, and are passed to striated muscle. Once reaching to the muscle, they encyst, or become enclosed in a capsule. Humans can become infected by eating contaminated pork, horse meat, or wild carnivorus animals such as cat, fox, or bear. Epidemology Trichinosis is a disease caused by the worm. It occurs around most parts of the world, and infects majority of humans. It ranges from North America and Europe, to Japan, China and Tropical Africa. Morphology Males of T. spiralis measure about1.4 and 1.6 mm long, and are more flat at anterior end than posterior end. The anus is seen in the terminal position, and they have a large copulatory pseudobursa on both the side. The females of T. spiralis are nearly twice the size of the males, and have an anal aperture situated terminally. -

Anti-Trichinella Antibodies in Breeding Pigs Farmed Under Controlled

Pozio et al. Parasites Vectors (2021) 14:417 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04920-1 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Animal welfare and zoonosis risk: anti-Trichinella antibodies in breeding pigs farmed under controlled housing conditions Edoardo Pozio1, Mario Celli2, Alessandra Ludovisi1, Maria Interisano1, Marco Amati1 and Maria Angeles Gómez‑Morales1* Abstract Background: Domesticated pigs are the main source of Trichinella sp. infections for humans, particularly when reared in backyards or free‑ranging. In temperate areas of southern Europe, most pigs are farmed under controlled housing conditions, but sows and sometimes fattening pigs have access to outdoors to improve animal welfare. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether outdoor access of breeding pigs farmed under controlled housing conditions can represent a risk for Trichinella sp. transmission when the farm is located in an agricultural area interspersed with wooded areas and badlands, where Trichinella spp. could be present in wildlife. Methods: Serum samples were collected from 63 breeding sows and one boar before and after their access to an open fenced area for 2 months and from 84 pigs that never had outdoor access. Samples were screened for anti‑Trich- inella antibodies by ELISA, and positive sera were confrmed using Western blot (Wb) excretory/secretory antigens. To detect Trichinella sp. larvae, muscle tissues from serologically positive and negative pigs were tested by artifcial digestion. Results: Thirteen (20.6%) sows and one boar tested positive with both ELISA and Wb. No larvae were detected in muscle samples of serologically positive and serologically negative pigs. Positive serum samples were then tested by Wb using crude worm extract as antigens. -

New Aspects of Human Trichinellosis: the Impact of New Trichinella Species F Bruschi, K D Murrell

15 REVIEW Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.78.915.15 on 1 January 2002. Downloaded from New aspects of human trichinellosis: the impact of new Trichinella species F Bruschi, K D Murrell ............................................................................................................................. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:15–22 Trichinellosis is a re-emerging zoonosis and more on anti-inflammatory drugs and antihelminthics clinical awareness is needed. In particular, the such as mebendazole and albendazole; the use of these drugs is now aided by greater clinical description of new Trichinella species such as T papuae experience with trichinellosis associated with the and T murrelli and the occurrence of human cases increased number of outbreaks. caused by T pseudospiralis, until very recently thought to The description of new Trichinella species, such as T murrelli and T papuae, as well as the occur only in animals, requires changes in our handling occurrence of outbreaks caused by species not of clinical trichinellosis, because existing knowledge is previously recognised as infective for humans, based mostly on cases due to classical T spiralis such as T pseudospiralis, now render the clinical picture of trichinellosis potentially more compli- infection. The aim of the present review is to integrate cated. Clinicians and particularly infectious dis- the experiences derived from different outbreaks around ease specialists should consider the issues dis- the world, caused by different Trichinella species, in cussed in this review when making a diagnosis and choosing treatment. order to provide a more comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment. SYSTEMATICS .......................................................................... Trichinellosis results from infection by a parasitic nematode belonging to the genus trichinella. -

Trichinella Nativa in a Black Bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 2005 Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire D.E. Hill Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory, [email protected] H.R. Gamble National Academy of Sciences, Washington D.S. Zarlenga Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory & Bovine Functions and Genomics Laboratory C. Cross Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory J. Finnigan New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories, Concord Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Hill, D.E.; Gamble, H.R.; Zarlenga, D.S.; Cross, C.; and Finnigan, J., "Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire" (2005). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 2244. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/2244 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Veterinary Parasitology 132 (2005) 143–146 www.elsevier.com/locate/vetpar Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire D.E. Hill a,*, H.R. Gamble c, D.S. Zarlenga a,b, C. Coss a, J. Finnigan d a United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Animal and Natural Resources Institute, Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory, Building 1044, BARC-East, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA b Bovine Functions and Genomics Laboratory, Building 1044, BARC-East, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA c National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, USA d The Food Safety Microbiology Unit, New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories, Concord, NH, USA Abstract A suspected case of trichinellosis was identified in a single patient by the New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories in Concord, NH. -

Trichinella Britovi

Pozio et al. Parasites Vectors (2020) 13:520 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04394-7 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Diferences in larval survival and IgG response patterns in long-lasting infections by Trichinella spiralis, Trichinella britovi and Trichinella pseudospiralis in pigs Edoardo Pozio1, Giuseppe Merialdi2, Elio Licata3, Giacinto Della Casa4, Massimo Fabiani1, Marco Amati1, Simona Cherchi1, Mattia Ramini2, Valerio Faeti4, Maria Interisano1, Alessandra Ludovisi1, Gianluca Rugna2, Gianluca Marucci1, Daniele Tonanzi1 and Maria Angeles Gómez‑Morales1* Abstract Background: Domesticated and wild swine play an important role as reservoir hosts of Trichinella spp. and a source of infection for humans. Little is known about the survival of Trichinella larvae in muscles and the duration of anti‑ Trichinella antibodies in pigs with long‑lasting infections. Methods: Sixty pigs were divided into three groups of 20 animals and infected with 10,000 larvae of Trichinella spiralis, Trichinella britovi or Trichinella pseudospiralis. Four pigs from each group were sacrifced at 2, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months post‑infection (p.i.) and the number of larvae per gram (LPG) of muscles was calculated. Serum samples were tested by ELISA and western blot using excretory/secretory (ES) and crude antigens. Results: Trichinella spiralis showed the highest infectivity and immunogenicity in pigs and larvae survived in pig mus‑ cles for up to 2 years p.i. In these pigs, the IgG level signifcantly increased at 30 days p.i. and reached a peak at about 60 days p.i., remaining stable until the end of the experiment. In T. britovi-infected pigs, LPG was about 70 times lower than for T. -

"Structure, Function and Evolution of the Nematode Genome"

Structure, Function and Advanced article Evolution of The Article Contents . Introduction Nematode Genome . Main Text Online posting date: 15th February 2013 Christian Ro¨delsperger, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany Adrian Streit, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany Ralf J Sommer, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany In the past few years, an increasing number of draft gen- numerous variations. In some instances, multiple alter- ome sequences of multiple free-living and parasitic native forms for particular developmental stages exist, nematodes have been published. Although nematode most notably dauer juveniles, an alternative third juvenile genomes vary in size within an order of magnitude, com- stage capable of surviving long periods of starvation and other adverse conditions. Some or all stages can be para- pared with mammalian genomes, they are all very small. sitic (Anderson, 2000; Community; Eckert et al., 2005; Nevertheless, nematodes possess only marginally fewer Riddle et al., 1997). The minimal generation times and the genes than mammals do. Nematode genomes are very life expectancies vary greatly among nematodes and range compact and therefore form a highly attractive system for from a few days to several years. comparative studies of genome structure and evolution. Among the nematodes, numerous parasites of plants and Strikingly, approximately one-third of the genes in every animals, including man are of great medical and economic sequenced nematode genome has no recognisable importance (Lee, 2002). From phylogenetic analyses, it can homologues outside their genus. One observes high rates be concluded that parasitic life styles evolved at least seven of gene losses and gains, among them numerous examples times independently within the nematodes (four times with of gene acquisition by horizontal gene transfer. -

Morphology, Life Cycle, Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis of Trichinella Spiralis

Paper No. : 08 Biology of Parasitism Module : 26 Morphology, Life Cycle, Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis of Trichinella Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Neeta Sehgal Head, Department of Zoology, University of Delhi Paper Coordinator: Dr. Pawan Malhotra ICGEB, New Delhi Content Writer: Dr. Rita Rath Dyal Singh College, University of Delhi Content Reviewer: Prof. Virender Kumar Bhasin Department of Zoology, University of Delhi 1 Biology of Parasitism ZOOLOGY Morphology, Life Cycle and Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis of Trichinella Description of Module Subject Name ZOOLOGY Paper Name Biology of Parasitism- ZOOL OO8 Module Name/Title Morphology, Life Cycle, Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis of Trichinella Module Id 26; Morphology, Life Cycle, Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis Keywords Trichinosis, pork worm, encysted larva, striated muscle , intestinal parasite Contents 1. Learning Outcomes 2. History 3. Geographical Distribution 4. Habit and Habitat 5. Morphology 5.1. Adult 5.2. Larva 6. Life Cycle 7. Pathogenicity 7.1. Diagnosis 7.2. Treatment 7.3. Prophylaxis 8. Phylogenetic Position 9. Genomics 10. Proteomics 11. Summary 2 Biology of Parasitism ZOOLOGY Morphology, Life Cycle and Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis of Trichinella 1. Learning Outcomes This unit will help to: Understand the medical importance of Trichinella spiralis. Identify the male and female worm from its morphological characteristics. Explain the importance of hosts in the life cycle of Trichinella spiralis. Diagnose the symptoms of the disease caused by the parasite. Understand the genomics and proteomics of the parasite to be able to design more accurate diagnostic, preventive, curative measures. Suggest various methods for the prevention and control of the parasite. Trichinella spiralis (Pork worm) Classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Nematoda Class: Adenophorea Order: Trichocephalida Superfamily: Trichinelloidea Genus: Trichinella Species: spiralis 2. -

Trichinellosis Outbreak Due to Wild Boar Meat Consumption in Southern

Turiac et al. Parasites & Vectors (2017) 10:107 DOI 10.1186/s13071-017-2052-5 LETTERTOTHEEDITOR Open Access Trichinellosis outbreak due to wild boar meat consumption in southern Italy Iulia Adelina Turiac1,2, Maria Giovanna Cappelli2, Rita Olivieri3, Raffaele Angelillis3, Domenico Martinelli2, Rosa Prato2* and Francesca Fortunato2 Abstract We report a Trichinella britovi outbreak investigated during February-March 2016 in southern Italy. The source of infection was meat from infected wild boars that were illegally hunted and, hence, not submitted to post-mortem veterinary inspection. Thirty persons reported having eaten raw dried homemade sausages; five cases of trichinellosis were confirmed. Wild game meat consumers need to be educated about the risk for trichinellosis. Keywords: Trichinella britovi, Trichinellosis, Italy, Wild boar meat, Zoonosis Letter to the Editor presence of Trichinella, as per the EU legislation, and con- In the European countries, the wildlife and domestic sumed as raw dried homemade sausages. reservoirs of Trichinella spp. still pose a risk for humans, A 36 year-old hunter was admitted to the “Casa Sollievo leading to outbreaks. Wild carnivore mammals are of della Sofferenza” Hospital, San Giovanni Rotondo city particular importance since a large number of hunted on 25 January 2016, suffering from fever (temperature animals escape veterinary control [1]. According to the 40–41 °C), myalgia, facial and periorbital swelling, epidemiological data the European Centre for Disease diarrhoea, vomiting, abdominal pain and night sweating. Prevention and Control (ECDC), trichinellosis is most These symptoms were developed 20 days before hospi- prevalent in eastern Europe but also in Italy and Spain talisation. Laboratory analysis showed marked eosinophilia where outbreaks were reported in the past 10 years [2]. -

Comparative Genomics of the Major Parasitic Worms

Comparative genomics of the major parasitic worms International Helminth Genomes Consortium Supplementary Information Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 Contributions from Consortium members ..................................................................................... 5 Methods .................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Sample collection and preparation ................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Data production, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (WTSI) ........................................................................ 12 DNA template preparation and sequencing................................................................................................. 12 Genome assembly ........................................................................................................................................ 13 Assembly QC ................................................................................................................................................. 14 Gene prediction ............................................................................................................................................ 15 Contamination screening ............................................................................................................................