Fossil Fuel Divestment Strategies: Financial and Carbon Related

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divestment May Burst the Carbon Bubble If Investors' Beliefs Tip To

Divestment may burst the carbon bubble if investors’ beliefs tip to anticipating strong future climate policy Birte Ewers,1;2;∗ Jonathan F. Donges,1;3;∗;# Jobst Heitzig1, Sonja Peterson4 1Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Member of the Leibniz Association, P.O. Box 60 12 03, 14412 Potsdam, Germany 2Department of Economics, University of Kiel, Olshausenstraße 40, 24098 Kiel, Germany 3Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, Kraftriket¨ 2B, 114 19 Stockholm, Sweden 4Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Kiellinie 66, 24105 Kiel, Germany ∗The first two authors share the lead authorship. #To whom correspondence should be addressed; E-mail: [email protected] February 21, 2019 To achieve the ambitious aims of the Paris climate agreement, the majority of fossil-fuel reserves needs to remain underground. As current national govern- ment commitments to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions are insufficient by far, actors such as institutional and private investors and the social movement on divestment from fossil fuels could play an important role in putting pressure on national governments on the road to decarbonization. Using a stochastic arXiv:1902.07481v1 [q-fin.GN] 20 Feb 2019 agent-based model of co-evolving financial market and investors’ beliefs about future climate policy on an adaptive social network, here we find that the dy- namics of divestment from fossil fuels shows potential for social tipping away from a fossil-fuel based economy. Our results further suggest that socially responsible investors have leverage: a small share of 10–20 % of such moral investors is sufficient to initiate the burst of the carbon bubble, consistent with 1 the Pareto Principle. -

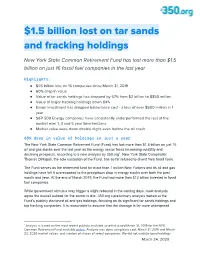

$1.5 Billion Lost on Tar Sands and Fracking Holdings

$1.5 billion lost on tar sands and fracking holdings New York State Common Retirement Fund has lost more than $1.5 billion on just 16 fossil fuel companies in the last year Highlights: ● $1.5 billion loss on 16 companies since March 31, 2019 ● 60% drop in value ● Value of tar sands holdings has dropped by 57% from $2 billion to $850 million ● Value of major fracking holdings down 84% ● Exxon investment has dropped below base cost - a loss of over $500 million in 1 year ● S&P 500 Energy companies have consistently underperformed the rest of the market over 1, 3 and 5 year time horizons ● Market value were down double digits even before the oil crash 60% drop in value of holdings in just a year The New York State Common Retirement Fund (Fund) has lost more than $1.5 billion on just 16 oil and gas stocks over the last year as the energy sector faces increasing volatility and declining prospects, according to a new analysis by 350.org1. New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, the sole custodian of the Fund, has so far refused to divest from fossil fuels. The Fund serves as the retirement fund for more than 1 million New Yorkers and its oil and gas holdings have left it overexposed to the precipitous drop in energy stocks over both the past month and year. At the end of March 2019, the Fund had more than $13 billion invested in fossil fuel companies. While government stimulus may trigger a slight rebound in the coming days, most analysts agree the overall outlook for the sector is dim. -

Ad Hoc Committee on Fossil Fuel Divestment Report

TO: Tilak Lal, Chair, Joint Committee on Investments; Vice Chair, Rutgers University Board of Trustees J. Michael Gower, Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, Rutgers University FROM: Ad Hoc Committee on Fossil Fuel Divestment SUBJECT: Divestment of the Rutgers University Endowment from Fossil Fuel Investments DATE: February 22, 2021 Introduction In spring 2020, the Joint Committee on Investments, which sets overall policy for the investment of the Rutgers University endowment, received a request from a student group called the Endowment Justice Collective to divest from fossil fuels. The chair of the Joint Committee on Investments and the university’s chief financial officer made a preliminary determination that the students’ request appeared to meet the standards outlined in the Advisory Statement on Divestment within the university’s Investment Policy. As prescribed by this policy, an ad hoc committee composed of faculty, students, and staff was charged to consider the divestment request based on university policy and to make recommendations based on its review.1 Fossil Fuels in the Rutgers University Endowment The Ad Hoc Committee defined fossil fuel investments as investments in any company or fund whose primary business is the exploration or extraction of fossil fuels, including coal, oil, and natural gas, or whose primary business supports this sector with infrastructure and other services. This definition is consistent with the nature of the divestment request received in spring 2020. Currently, approximately 5% of the university’s $1.5 billion endowment consists of fossil fuel investments. Sixty percent of these investments are in private funds, with the remainder in public equity or fixed income funds. -

Climate Change: Active Stewardship Vs. Divestment

HNW_NRG_B_Inset_Mask Climate change: Active Stewardship vs. Divestment At RBC Global Asset Management (RBC GAM)1, we believe that climate change is a material and systemic risk that has the potential to impact the global economy, markets and society as a whole. As an asset manager and fiduciary of our clients’ assets, we have an important responsibility to consider all material factors that may impact the performance of our investments. In 2020, we took steps to formalize the actions we are taking to address climate change with the launch of Our approach to climate change. A cornerstone of this approach is active stewardship as an effective mechanism to motivate companies to build strategies that enable climate mitigation* and adaptation**. Some investors who are concerned about the impact of in extreme cases, the filing of lawsuits. As global investors climate change and are seeking to align their investment continue to integrate climate change into their investment strategies with these views have chosen a divestment decisions, active managers use both engagement and proxy approach. While RBC GAM does offer divestment solutions, voting as a means of better understanding and influencing we believe that the best approach to support the transition the activities or behaviour of issuers. to a low-carbon economy is through active stewardship. Engagement Active stewardship Engagement involves meeting with the boards and Active stewardship refers to the suite of actions investors management of issuers, typically corporations, and learning can take to better understand and influence the activities or about how they are approaching strategic opportunities and behaviour of issuers. It can be thought of as a conversation material risks in their business. -

ASI Position Statement – Fossil Fuels April 2021

ASI Position Statement – Fossil Fuels April 2021 “ At ASI, consideration of climate-change risks and opportunities is an integral part of our investment process across all asset classes and sectors. We carefully consider fossil fuel related risks and the ability to transition to alternatives in our investment decisions.” 02 ASI Position Statement Fossil Fuels – Our Approach for Investments Financial risks related to fossil fuels are becoming more material the transition from more carbon-intensive fuels to gas where as pressure to decarbonise the global economy is growing. alternatives are limited. However, we also consider the risk of gas Aberdeen Standard Investments (ASI) fully acknowledges the role utilities and infrastructure becoming stranded in the medium to of fossil fuels in causing and further exacerbating climate change. long term. Transitioning directly to low-carbon energy sources We support the goals of the Paris Agreement, are members of the such as renewables is our preference and we strongly Net Zero Asset Manager initiative and believe that urgent action is encourage it. required to limit global warming to 1.5°C. This means aiming for a global net-zero emissions economy by 2050, in which fossil fuels Pounds of CO2 emitted per million Btu of energy will only play a minor role. On the path to that world, we need to transition to a low-carbon Natua as economy, in which fossil fuels are phased out and replaced with Gasoine cost effective and reliable alternatives. This needs to be a ‘just’ (witot ethano) transition where effects on communities, workers and energy Diese ue and security are carefully considered. -

Fossil Fuels Divestment

Fossil Fuels Divestment ww3.haverford.edu /fossilfuelsdivestment/ Dear Friends, Over the past year, many colleges and universities have investigated divestment of endowment from firms that have investments in fossil fuels as a way of applying financial leverage against the use of carbon- based energy while promoting alternative sources. Here at Haverford, the dialogue was initiated in the summer of 2012 by a number of thoughtful students who, consistent with a national campaign, specifically asked the College to freeze all endowment investments in 200 companies identified as having the greatest proven reserves of coal, oil, and natural gas and to unwind all existing investments in these companies over a five-year period. The matter was referred to our Board’s Committee on Investments and Social Responsibility (CISR), which includes Investment Committee representation, in order to explore what such a move could mean for Haverford. The students who initiated this conversation expressed profound concern about the effects of climate change arising from the burning of fossil fuels, and they have challenged the College to engage thoughtfully on how we as an institution and as a community can act within our sphere to mitigate this global threat. As an institution committed to values of ethical concern and social responsibility, the College commends these students for initiating this important conversation. The dialogue has been serious, positive, and informed by the understanding that we must balance needs with ambitions. The CISR’s deliberations on this matter included meetings with the concerned students as well as an open forum with the broader College community, and were supported by research conducted by the College’s investment office. -

Extracting Fossil Fuels from Your Portfoliosm

EXTRACTING FOSSIL FUELS FROM YOUR PORTFOLIOSM: An UPDATED Guide to Personal Divestment and Reinvestment ABOUT THE AUTHORS 350.org is a global network inspiring the world to rise to 100% of Green Century’s profits earned for managing the challenge of the climate crisis. Since its inception in the Green Century Funds belong to the founding group 2008, their online campaigns, grassroots organizing, and of environmental non-profit organizations, the Public mass public actions have been led from the bottom up Interest Research Groups (PIRGs), that started Green by people in 188 countries. Century in 1991. 350 means climate safety. To preserve our planet, Since 2005, Green Century’s Balanced Fund has been scientists tell us we must reduce the amount of CO2 in 100% fossil fuel free; it is an actively managed fund the atmosphere from its current levels of 400 parts per made up of the stocks and bonds of well-managed million to below 350 ppm. 350 is more than a number — companies. The Balanced Fund is almost 50% less it’s a symbol of where we need to head as a planet. carbon intensive than the S&P 500® Index as measured by the international data and analysis firm Trucost.1 The 350 works in a new way — everywhere at once using Green Century Equity Fund, which is also fossil fuel free, online tools to facilitate strategic offline action — under invests in the longest running sustainability index minus the belief that if a global grassroots movement holds the fossil fuel companies in that index. our leaders accountable to the realities of science and principles of justice, we can realize the solutions that For more information, click here or visit www. -

Climate Risk and the Fossil Fuel Industry: Two Feet High and Rising

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IssueLab Working Paper Climate Risk and the Fossil Fuel Industry: Two Feet High and Rising Jim Krane, Ph.D. Wallace S. Wilson Fellow in Energy Studies, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy © 2016 by the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy of Rice University This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy. This paper is a work in progress and has not been submitted for editorial review. Climate Risk and the Fossil Fuel Industry Keywords Climate change risk, fossil fuel, stranded assets, unburnable carbon, carbon bubble, carbon budget, divestment, carbon price, carbon tax, cap-and-trade, INDCs, COP 21, shareholder risk, leave it in the ground, greenhouse gas, GHG, decarbonization Introduction Burning coal, oil and natural gas is responsible for two-thirds of the world’s emissions of greenhouse gases. These same fuels also represent the economic mainstay of resource-rich countries and the world’s largest firms. Any steps humanity takes to reduce climate- warming emissions will damage commercial opportunities. Relief for the climate means danger for the fossil fuel business. Given the stakes, it bears asking: What, exactly, are the risks? How are they manifested and distributed? Luminaries such as the US president and the governor of the Bank of England have called for leaving large portions of oil, gas, and coal reserves in the ground. -

The Facts About Fossil Fuel Divestment

The Facts about Fossil Fuel Divestment Divestment is one of the most powerful statements that an institution can make with its money. It helps remove the social license that allows the fossil fuel industry to continue to emit dangerous pollutants into the atmosphere at low cost. The fossil fuel industry’s business model depends on its ability to burn all of the carbon in its reserves. To stay below 2 degrees Celsius of warming, scientists and economists say we must leave 80 percent of the current coal, oil and gas reserves in the ground. Simply put, to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change we can only burn less than 500 gigatons of carbon, while the fossil fuel industry currently holds 2,860 gigatons in its reserves. Our generation has a moral imperative to address climate change in a manner that is consistent with the urgency and severity of the crisis. Colleges and universities, for example, exist to educate new generations of young people. Pension funds exist to support the longterm health of their pension holders. The following facts, used in conversations with college administrators, pension trustees, finance professionals and other thought leaders we encounter in the divestment effort, can be helpful in debunking common misperceptions about fossil fuel divestment: 1. Fiduciary duty demands fossil fuel divestment Fiduciary responsibility, or fiduciary duty, is a legal term meaning that trustees must act in the best interest of the institution. For many institutional investors, this is interpreted to mean maximizing shortterm returns at the expense of all other factors. -

Fossil Fuel Divestment: a Moral, Environmental and Financial Imperative

Article 20 Bibliography: FOSSIL FUEL DIVESTMENT: A MORAL, ENVIRONMENTAL AND FINANCIAL IMPERATIVE. For an electronic version, contact [email protected] ABC report: Bill McKibben’s “Do the Math” Tour. April 29, 2013. http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2013/04/29/1933811/video-nightline-does-the- climate-math-with-bill-mckibben/ McKibben, Bill. Rolling Stone Magazine. The Reckoning: Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math.. July 19, 2012. http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/global-warmings-terrifying-new- math-20120719 Small, Fred. UU World.org. Fossil Fuel Divestment is Moral, Strategic: Money is an Instrument of Moral Choice. Summer 2013. http://www.uuworld.org/ideas/articles/285524.shtml Stephenson, Wen. Boston Phoenix. The New Abolitionists: Global Warming is the Great Moral Issue of Our Time. March 12, 2013. http://thephoenix.com/boston/news/151670-new-abolitionists-global-warming- is-the-great/ Release of the Fifth Assessment of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC ) (building momentum as the UN process moves toward a legally binding global carbon emissions agreement in 2015). Sept. 26, 2013. http://www.ipcc.ch/news_and_events/docs/ar5/ar5_wg1_headlines.pdf Secretary of State John Kerry. Press Statement: Release of the Fifth Assessment of the IPCC, Sept. 27, 2013. tp://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2013/09/214833.htm Carbon Tracker Initiative. Unburnable Carbon 2013: Wasted Capital and Stranded Assets. March, 2013. https://docs.google.com/file/d/1tsmQREK21woVhOQxS2bvmRgSydRbrSpI8BVkq_ RmOkDvrM7s47A5RkjpphX9/edit AP: College Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement Builds. May, 4, 2013. (citing AP S&P Capital IQ analysis) : http://www.utsandiego.com/news/2013/May/22/college- fossil-fuel-divestment-movement-builds/?#article-copy Forbes Magazine. -

The Case for Fossil Fuel Divestment a Guide for Auckland Council March 2017 B

The case for fossil fuel divestment A guide for Auckland Council March 2017 B. Forbes, S. Vincent, S. Hildebrandt, & E. Campbell The photographs in this report depict the effects of extreme weather events in the Pacific (namely cyclones Pam and Winston in Vanuatu and Fiji respectively), and one of the many efforts undertaken by Pacific peoples to fight back against the fossil fuel industry: the Pacific Climate Warrior blockade of the Newcastle coal port in Australia. Climate change is expected to increase the intensity of both these kinds of events. All photographs © Jeff Tan www.jefftanphotography.com For general enquiries about 350 Aotearoa, divestment and organising, please contact Niamh O’Flynn at [email protected] For enquiries about this report, please contact Blaze Forbes at [email protected] Executive Summary Divestment is the opposite of investment and consists of withdrawing and withholding funds from a problematic sector. Divestment undermines the legitimacy of the targeted sector and thereby builds pressure for change. Historically, divestment was a component of the successful international push against Apartheid in South Africa. Tobacco, alcohol, munitions, gambling and pornography have all been targets of divestment campaigns. Recently, divestment from fossil fuels has gained prominence as a means whereby investors may curb the problematic activities of the fossil fuel industry contributing to climate change. Globally, fossil fuel divestment is accelerating: $5.2 trillion has been divested to date, double the amount divested by 2015. A major conclusion of the research into fossil fuel divestment is that funds divested from fossil fuels perform better than fossil fuel-inclusive funds – that is, from a purely financial point of view, the case for fossil fuel divestment is robust. -

Resolution in Support of Divestment from Fossil Fuel Companies

Resolution in Support of Divestment from Fossil Fuel Companies WHEREAS, the leaders of 167 countries (including the United States) have agreed that any warming of the planet above 2°C (3.6°F) would be unsafe, and we have already (as of 2012) have raised the average surface temperature 0.8°C, causing far more damage than most scientists expected1; and, WHEREAS, this rapid temperature increase has exacerbated weather extremes including the intensification and/or the more frequent occurrence of hurricanes2, tropical storms2, heat waves3, floods4, droughts5, and wildfires6 and these extreme events have and will continue to negatively impact the U.S. economy. In 2012, the US accounted for 67% of the $160 billion lost globally due to natural catastrophes; and, WHEREAS, The current global effects of climate change include at least 150,000 annual deaths according to the World Health Organization7, and $1.2 trillion in annual economic losses according to the Climate Vulnerable Forum8; and Fossil fuels negatively impact human health via toxic pollutants, with a recent estimate of $345 billion per year in the United States alone due to coal extraction and burning; and, WHEREAS, according to the Carbon Tracker Institute, the proven coal, oil, and gas reserves of the top 200 fossil-fuel companies, and countries (e.g. Venezuela or Kuwait) which function similarly to fossil-fuel companies, equals about 2,795 gigatons of CO2, or five times the amount we can release to maintain a 2°C limit of planetary warming9; and, WHEREAS, the conditions resulting from climate change often disproportionately affect those who are marginalized, including low-income communities and communities of color—who have done the least to cause it and often have the least access to the tools to combat it-- and as a University we must ensure social and environmental justice by doing all we can to mitigate climate change and its impacts10; and, 1 http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2009/cop15/eng/11a01.pdf 2 “Climate Change and Sandy”, 15 Nov 2012.