Australian Coral Sea Heritage Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Military and Veterans' Health

Volume 16 Number 1 October 2007 Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health Deployment Health Surveillance Australian Defence Force Personnel Rehabilitation Blast Lung Injury and Lung Assist Devices Shell Shock The Journal of the Australian Military Medicine Association Every emergency is unique System solutions for Emergency, Transport and Disaster Medicine Different types of emergencies demand adaptable tools and support. We focus on providing innovative products developed with the user in mind. The result is a range of products that are tough, perfectly coordinated with each other and adaptable for every rescue operation. Weinmann (Australia) Pty. Ltd. – Melbourne T: +61-(0)3-95 43 91 97 E: [email protected] www.weinmann.de Weinmann (New Zealand) Ltd. – New Plymouth T: +64-(0)6-7 59 22 10 E: [email protected] www.weinmann.de Emergency_A4_4c_EN.indd 1 06.08.2007 9:29:06 Uhr Table of contents Editorial Inside this edition . 3 President’s message . 4 Editor’s message . 5 Commentary Initiating an Australian Deployment Health Surveillance Program . 6 Myers – The dawn of a new era . 8 Original Articles The Australian Defence Deployment Health Surveillance Program – InterFET Pilot Project . 9 Review Articles Rehabilitation of injured or ill ADF Members . 14 What is the effectiveness of lung assist devices in blast injury: A literature review . .17 Short Communications Unusual Poisons: Socrates’ Curse . 25 Reprinted Articles A contribution to the study of shell shock . 27 Every emergency is unique Operation Sumatra Assist Two . 32 System solutions for Emergency, Transport and Disaster Medicine Biography Surgeon Rear Admiral Lionel Lockwood . 35 Different types of emergencies demand adaptable tools and support. -

THE BATTLE of the CORAL SEA — an OVERVIEW by A.H

50 THE BATTLE OF THE CORAL SEA — AN OVERVIEW by A.H. Craig Captain Andrew H. Craig, RANEM, served in the RAN 1959 to 1988, was Commanding officer of 817 Squadron (Sea King helicopters), and served in Vietnam 1968-1979, with the RAN Helicopter Flight, Vietnam and No.9 Squadroom RAAF. From December 1941 to May 1942 Japanese armed forces had achieved a remarkable string of victories. Hong Kong, Malaya and Singapore were lost and US forces in the Philippines were in full retreat. Additionally, the Japanese had landed in Timor and bombed Darwin. The rapid successes had caught their strategic planners somewhat by surprise. The naval and army staffs eventually agreed on a compromise plan for future operations which would involve the invasion of New Guinea and the capture of Port Moresby and Tulagi. Known as Operation MO, the plan aimed to cut off the eastern sea approaches to Darwin and cut the lines of communication between Australia and the United States. Operation MO was highly complex and involved six separate naval forces. It aimed to seize the islands of Tulagi in the Solomons and Deboyne off the east coast of New Guinea. Both islands would then be used as bases for flying boats which would conduct patrols into the Coral Sea to protect the flank of the Moresby invasion force which would sail from Rabaul. That the Allied Forces were in the Coral Sea area in such strength in late April 1942 was no accident. Much crucial intelligence had been gained by the American ability to break the Japanese naval codes. -

Introduction of an Alien Fish Species in the Pilbara Region of Western

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 33 108–114 (2018) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.33(1).2018.108-114 Introduction of an alien fsh species in the Pilbara region of Western Australia Dean C. Thorburn1, James J. Keleher1 and Simon G. Longbottom1 1 Indo-Pacifc Environmental, PO Box 191, Duncraig East, Western Australia 6023, Australia. * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – Until recently rivers of the Pilbara region of north Western Australia were considered to be free of introduced fsh species. However, a survey of aquatic fauna of the Fortescue River conducted in March 2017 resulted in the capture of 19 Poecilia latipinna (Sailfn Molly) throughout a 25 km section of the upper catchment. This represented the frst record of an alien fsh species in the Pilbara region and the most northern record in Western Australia. Based on the size of the individuals captured, the distribution over which they were recorded and the fact that the largest female was mature, P. latipinna appeared to be breeding. While P. latipinna was unlikely to physically threaten native fsh species in the upper reaches of the Fortescue River, potential spatial and dietary competition may exist if it reaches downstream waters where native fsh diversity is higher and dietary overlap is likely. As P. latipinna has the potential to affect macroinvertebrate communities, some risk may also exist to the macroinvertebrate community of the Fortescue Marsh, which is located immediately downstream, and which is valued for its numerous short range endemic aquatic invertebrates. The current fnding indicated that despite the relative isolation of the river and presence of a low human population, this remoteness does not mean the river is safe from the potential impact of species introductions. -

Cape York Peninsula Parks and Reserves Visitor Guide

Parks and reserves Visitor guide Featuring Annan River (Yuku Baja-Muliku) National Park and Resources Reserve Black Mountain National Park Cape Melville National Park Endeavour River National Park Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park (CYPAL) Heathlands Resources Reserve Jardine River National Park Keatings Lagoon Conservation Park Mount Cook National Park Oyala Thumotang National Park (CYPAL) Rinyirru (Lakefield) National Park (CYPAL) Great state. Great opportunity. Cape York Peninsula parks and reserves Thursday Possession Island National Park Island Pajinka Bamaga Jardine River Resources Reserve Denham Group National Park Jardine River Eliot Creek Jardine River National Park Eliot Falls Heathlands Resources Reserve Captain Billy Landing Raine Island National Park (Scientific) Saunders Islands Legend National Park National park Sir Charles Hardy Group National Park Mapoon Resources reserve Piper Islands National Park (CYPAL) Wen Olive River loc Conservation park k River Wuthara Island National Park (CYPAL) Kutini-Payamu Mitirinchi Island National Park (CYPAL) Water Moreton (Iron Range) Telegraph Station National Park Chilli Beach Waterway Mission River Weipa (CYPAL) Ma’alpiku Island National Park (CYPAL) Napranum Sealed road Lockhart Lockhart River Unsealed road Scale 0 50 100 km Aurukun Archer River Oyala Thumotang Sandbanks National Park Roadhouse National Park (CYPAL) A r ch KULLA (McIlwraith Range) National Park (CYPAL) er River C o e KULLA (McIlwraith Range) Resources Reserve n River Claremont Isles National Park Coen Marpa -

Dr Allan Young Shoulder Surgeon Dr Allan Young MBBS Mspmed Phd FRACS (Orth)

curriculum vitae dr allan young shoulder surgeon Dr Allan Young MBBS MspMed PhD FRACS (Orth) [email protected] sydneyshoulder.com.au Sydney Shoulder Specialists Suite 201, Level 2, 156 Paci�ic Highway St Leonards, NSW, Australia, 2065 Phone 61 2 9460 7615 Fax 61 2 9460 6064 page 2 2008 FRACS Fellowship (Orthopaedic) Royal Australasian College of Surgeons 2005 PhD Doctor of Philosophy University of Sydney 2003 MSpMed Masters of Sports Medicine University of New South Wales education 1996 MBBS Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery University of Queensland page 3 Visiting Medical Of�icer North Shore Private Hospital Mater Hospital St Vincent’s Private Hospital Dubbo Private Hospital Dubbo Base Hospital Surgeon Commander (Orthopaedic Surgeon) Royal Australian Naval Reserves Director Sydney Shoulder Research Institute current appointments current page 4 2010 Senior Lecturer in Orthopaedic Surgery to University of Sydney 2014 Sydney, AUSTRALIA 2010 Orthopaedic Surgeon (Staff Specialist) to Royal North Shore Hospital 2014 Sydney, AUSTRALIA 2009 Postgraduate Fellow in Shoulder Surgery to Supervisor: Dr Gilles Walch 2010 Lyon, FRANCE 2009 Postgraduate Fellow in Shoulder & Elbow Surgery to Supervisors: Prof David Sonnabend & 2010 Dr Jeffery Hughes previous appointments Royal North Shore Hospital Sydney, AUSTRALIA page 5 2004 Advanced Trainee to Australian Orthopaedic Association 2008 Sydney, AUSTRALIA 2002 Doctor of Philosophy studies to Royal North Shore Hospital 2004 Sydney, AUSTRALIA 11/2002 Visiting Researcher to Jo Miller -

Your Great Barrier Reef

Your Great Barrier Reef A masterpiece should be on display but this one hides its splendour under a tropical sea. Here’s how to really immerse yourself in one of the seven wonders of the world. Yep, you’re going to get wet. southern side; and Little Pumpkin looking over its big brother’s shoulder from the east. The solar panels, wind turbines and rainwater tanks that power and quench this island are hidden from view. And the beach shacks are illusory, for though Pumpkin Island has been used by families and fishermen since 1964, it has been recently reimagined by managers Wayne and Laureth Rumble as a stylish, eco- conscious island escape. The couple has incorporated all the elements of a casual beach holiday – troughs in which to rinse your sandy feet, barbecues on which to grill freshly caught fish and shucking knives for easy dislodgement of oysters from the nearby rocks – without sacrificing any modern comforts. Pumpkin Island’s seven self-catering cottages and bungalows (accommodating up to six people) are distinguished from one another by unique decorative touches: candy-striped deckchairs slung from hooks on a distressed weatherboard wall; linen bedclothes in this cottage, waffle-weave in that; mint-green accents here, blue over there. A pair of legs dangles from one (Clockwise from top left) Book The theme is expanded with – someone has fallen into a deep Pebble Point cottage for the unobtrusively elegant touches, afternoon sleep. private deck pool; “self-catering” such as the driftwood towel rails The island’s accommodation courtesy of The Waterline and the pottery water filters in is self-catering so we arrive restaurant; accommodations Pumpkin Island In summer the caterpillars Feel like you’re marooned on an just the right shade of blue. -

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

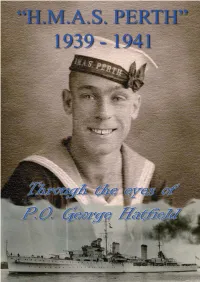

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

Report of Children Overboard: Dissemination and Early Doubts

51 Chapter 4 The Report of Children Overboard: Dissemination and Early Doubts Introduction 4.1 As discussed in the previous chapter, the report that a child or children had been thrown overboard from SIEV 4 originated in the telephone conversation between Commander Banks and Brigadier Silverstone on the morning of Sunday 7 October 2001. 4.2 At about 11.15am (AEST) on the same day, that report was made public by Mr Philip Ruddock, Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, during the course of a press conference.1 As Ms Jennifer Bryant remarked in her report: In total, only around four hours elapsed between the commencement of boarding [of SIEV 04 by HMAS Adelaide] and reports [of children thrown overboard] being made public in the media.2 4.3 In this chapter, the Committee first discusses how an oral and uncorroborated report made in the midst of a complex tactical operation came to be disseminated so quickly and so widely. The Committee then outlines how doubts concerning the veracity of the report arose in the Defence chain of command, and the point at which different elements in that chain reached the conclusion that the incident had not occurred. Finally, the Committee discusses how photographs taken of the sinking of SIEV 4 on 8 October came to be publicly misrepresented as being photographs of the ‘children overboard’ event. 4.4 In the following chapter, the Committee will consider the role played by a range of agencies and individuals in relation to attempts to correct the original and mistaken report that children had been thrown overboard. -

The Lower Bathyal and Abyssal Seafloor Fauna of Eastern Australia T

O’Hara et al. Marine Biodiversity Records (2020) 13:11 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-020-00194-1 RESEARCH Open Access The lower bathyal and abyssal seafloor fauna of eastern Australia T. D. O’Hara1* , A. Williams2, S. T. Ahyong3, P. Alderslade2, T. Alvestad4, D. Bray1, I. Burghardt3, N. Budaeva4, F. Criscione3, A. L. Crowther5, M. Ekins6, M. Eléaume7, C. A. Farrelly1, J. K. Finn1, M. N. Georgieva8, A. Graham9, M. Gomon1, K. Gowlett-Holmes2, L. M. Gunton3, A. Hallan3, A. M. Hosie10, P. Hutchings3,11, H. Kise12, F. Köhler3, J. A. Konsgrud4, E. Kupriyanova3,11,C.C.Lu1, M. Mackenzie1, C. Mah13, H. MacIntosh1, K. L. Merrin1, A. Miskelly3, M. L. Mitchell1, K. Moore14, A. Murray3,P.M.O’Loughlin1, H. Paxton3,11, J. J. Pogonoski9, D. Staples1, J. E. Watson1, R. S. Wilson1, J. Zhang3,15 and N. J. Bax2,16 Abstract Background: Our knowledge of the benthic fauna at lower bathyal to abyssal (LBA, > 2000 m) depths off Eastern Australia was very limited with only a few samples having been collected from these habitats over the last 150 years. In May–June 2017, the IN2017_V03 expedition of the RV Investigator sampled LBA benthic communities along the lower slope and abyss of Australia’s eastern margin from off mid-Tasmania (42°S) to the Coral Sea (23°S), with particular emphasis on describing and analysing patterns of biodiversity that occur within a newly declared network of offshore marine parks. Methods: The study design was to deploy a 4 m (metal) beam trawl and Brenke sled to collect samples on soft sediment substrata at the target seafloor depths of 2500 and 4000 m at every 1.5 degrees of latitude along the western boundary of the Tasman Sea from 42° to 23°S, traversing seven Australian Marine Parks. -

FROM CRADLE to GRAVE? the Place of the Aircraft

FROM CRADLE TO GRAVE? The Place of the Aircraft Carrier in Australia's post-war Defence Force Subthesis submitted for the degree of MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES at the University College The University of New South Wales Australian Defence Force Academy 1996 by ALLAN DU TOIT ACADEMY LIBRARy UNSW AT ADFA 437104 HMAS Melbourne, 1973. Trackers are parked to port and Skyhawks to starboard Declaration by Candidate I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text of the thesis. Allan du Toit Canberra, October 1996 Ill Abstract This subthesis sets out to study the place of the aircraft carrier in Australia's post-war defence force. Few changes in naval warfare have been as all embracing as the role played by the aircraft carrier, which is, without doubt, the most impressive, and at the same time the most controversial, manifestation of sea power. From 1948 until 1983 the aircraft carrier formed a significant component of the Australian Defence Force and the place of an aircraft carrier in defence strategy and the force structure seemed relatively secure. Although cost, especially in comparison to, and in competition with, other major defence projects, was probably the major issue in the demise of the aircraft carrier and an organic fixed-wing naval air capability in the Australian Defence Force, cost alone can obscure the ftindamental reordering of Australia's defence posture and strategic thinking, which significantly contributed to the decision not to replace HMAS Melbourne. -

Bertarelli Programme in Marine Science Coral Reef Expedition to the British Indian Ocean Territory, April 2019

Bertarelli Programme in Marine Science Coral Reef Expedition to the British Indian Ocean Territory, April 2019 Figure 1: Early signs of coral reef recovery in BIOT, Takamaka, Salomon 1 | P a g e Executive Summary The Bertarelli Programme in Marine Science Coral Reef Expedition to the British Indian Ocean Territory on Coral Reef Condition took place in April 2019, and involved Bangor University, Oxford University, University College of London, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, USA. The team joined the British Patrol Vessel Grampian Frontier in Male, Maldives on 6th April and travelled south, arriving Diego Garcia on 27th April 2019. Exceptionally calm seas were experienced until 17th April, and then rough conditions which progressively worsened until 27th April. Thirteen experienced scientific divers including a Medical Officer conducted a total of 113 dives, equating to 301 person dives and 318 hours underwater over the period. The team undertook 7 scientific tasks to investigate the current condition of the coral reefs at 34 sites across the archipelago as follows: Tasks 1 & 2: Coral condition, cover, juveniles, and water temperatures (C. Sheppard, A. Sheppard). Task 3: Extend video archive for long term assessment of coral reef benthic community structure (J. Turner, R. Roche, J. Sannassy Pilly). Task 4: Three-dimensional determination of reef structural complexity and spatial analysis of coral recruitment (D. Bayley, A. Mogg). Tasks 5 & 6: Spatiotemporal variations in internal wave driven upwelling and resilience potential across the Chagos Archipelago (G. Williams, M. Fox, A. Heenan, R. Roche) Task 7: Coral reef recovery and resilience (B. Wilson and A. Rose). The coral reefs of the Archipelago are still in an erosional state with very low coral cover 3 years after the back to back bleaching events of 2015/2016. -

The Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea 20 Tom C.L

The Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea 20 Tom C.L. Bridge, Robin J. Beaman, Pim Bongaerts, Paul R. Muir, Merrick Ekins, and Tiffany Sih Abstract agement approaches that explicitly considered latitudinal The Coral Sea lies in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, bor- and cross-shelf gradients in the environment resulted in dered by Australia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon mesophotic reefs being well-represented in no-take areas in Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and the Tasman Sea. The the GBR. In contrast, mesophotic reefs in the Coral Sea Great Barrier Reef (GBR) constitutes the western margin currently receive little protection. of the Coral Sea and supports extensive submerged reef systems in mesophotic depths. The majority of research on Keywords the GBR has focused on Scleractinian corals, although Mesophotic coral ecosystems · Coral · Reef other taxa (e.g., fishes) are receiving increasing attention. · Queensland · Australia To date, 192 coral species (44% of the GBR total) are recorded from mesophotic depths, most of which occur shallower than 60 m. East of the Australian continental 20.1 Introduction margin, the Queensland Plateau contains many large, oce- anic reefs. Due to their isolated location, Australia’s Coral The Coral Sea lies in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, cover- Sea reefs remain poorly studied; however, preliminary ing an area of approximately 4.8 million square kilometers investigations have confirmed the presence of mesophotic between latitudes 8° and 30° S (Fig. 20.1a). The Coral Sea is coral ecosystems, and the clear, oligotrophic waters of the bordered by the Australian continent on the west, Papua New Coral Sea likely support extensive mesophotic reefs.