Reprint Requests to Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aeroallergen-Induced Th2 Inflammation Endogenous And

Endogenous and Exogenous IL-6 Inhibit Aeroallergen-Induced Th2 Inflammation Jingming Wang, Robert J. Homer, Qingsheng Chen and Jack A. Elias This information is current as of September 26, 2021. J Immunol 2000; 165:4051-4061; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.4051 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/165/7/4051 Downloaded from References This article cites 61 articles, 22 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/165/7/4051.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. http://www.jimmunol.org/ • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average by guest on September 26, 2021 Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2000 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. Endogenous and Exogenous IL-6 Inhibit Aeroallergen-Induced Th2 Inflammation1 Jingming Wang,* Robert J. Homer,† Qingsheng Chen,* and Jack A. Elias2* Chronic Th2-dominated inflammation and exaggerated IL-6 production are characteristic features of the asthmatic airway. To understand the processes that are responsible for the chronicity of this response and the role(s) of IL-6 in the regulation of airway Th2 inflammation, we compared the responses induced by OVA in sensitized wild-type mice, IL-6 deficient (؊/؊) mice, and transgenic mice in which IL-6 was overexpressed in the airway (CC10-IL-6 mice). -

Approaches for Assessing Health Risks from Complex Mixtures in Indoor Air: a Panel Overview by Carol J

Environmental Health Perspectives Vol. 95, pp. 135-143, 1991 Approaches for Assessing Health Risks from Complex Mixtures in Indoor Air: A Panel Overview by Carol J. Henry,* Lawrence Fishbein,* William J. Meggs,t Nicholas A. Ashford,' Paul A. Schulte,§ Henry Anderson,/' J. Scott Osborne,' and Daniel W. Sepkovictt Critical to a more definitive human health assessment ofthe potential health risks from exposure to complex mixtures in indoor air is the need for a more definitive clinical measure and etiology ofthe helath effects ofcomplex mixtures. This panel overview highlights six ofthe eight presentations ofthe conference panel discussion and features a number ofthe major topical areas of indoor air concern. W. G. Meggs assessed clinical research priorities with primary focus on the role ofvolatile organic chemicals in human health, recognizing the areas where definitive data are lacking. By recogniz- ing many types ofchemical sensitivity, it may be possible to design studies that can illuminate the mechanisms by which chemical exposure may cause disease. The critically important topic of multiple chemical sensitivity was discussed by N. A. Ashford, who identified four high risk groups and defined the demographics ofthese groups. P. A. Schulte address- ed the issue ofbiological markers ofsusceptibility with specific considerations ofboth methodologia and societal aspects that may be operative in the ability to detect innate or inborne differences between individuals and populations. Three case studies were reviewed. H. Anderson discussed the past and present priorities from a public health perspective, focusing on those issues dealing with exposures to environmental tobacco smoke and formaldehyde off-gassing from materials used in mobile homeconstruction. -

Aeroallergen Sensitization and Allergic Disease Phenotypes in Asia

REVIEW ARTICLE Asian Pacific Journal of Allergy and Immunology Aeroallergen sensitization and allergic disease phenotypes in Asia Elizabeth Huiwen Tham,1,2 Alison Joanne Lee,1,2 Hugo Van Bever1,2 Abstract Allergic diseases are on the rise in Asia. Aeroallergen exposure is a strong risk factor for sensitization, development and severity of atopic diseases, especially in the Asian paediatric population. Geographical and seasonal variations in aeroallergen sensitization are seen even within Asian countries and changes in aeroallergen sensitization patterns have been observed over time. Some possible reasons include climate change as well as rapid urbanization and improved sanitation which follow socioeconomic development. House dust mite allergy is present in up to 90% of Asian atopic patients, far exceeding that which is seen in Western populations which report prevalences of only 50% to 70%. Pollen and animal dander affect less than 10% of Asian patients as compared to 40-70% of individuals with asthma and allergic rhinitis living in the West, a burden almost equivalent to the dust mite burden in those regions. There is thus a pressing need for preventive measures to reduce dust mite sensitization in Asian children today. Keywords: Aeroallergen, Asia, allergy, house dust mites, sensitization From: Corresponding author: 1 Department of Paediatrics, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National Elizabeth Huiwen Tham University of Singapore Department of Paediatrics, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National 2 Khoo Teck Puat-National University -

Xolair® (Omalizumab)

Xolair® (omalizumab) When requesting Xolair® (omalizumab), the individual requiring treatment must be diagnosed with one of the following FDA-approved indications and meet the specific coverage guidelines and applicable safety criteria for the covered indications. FDA-approved indications • Xolair® (omalizumab) is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe persistent asthma in individuals with a positive skin test or in vitro reactivity to a perennial aeroallergen and symptoms that are inadequately controlled with inhaled corticosteroids. • Xolair® (omalizumab) is indicated for the treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria in individuals who remain symptomatic despite treatment with a histamine-1 (H1) antihistamine. Approved Off-label Compendial use • None Coverage Guidelines Moderate to Severe Persistent Asthma The individual must meet all of the following criteria for initial approval: • Diagnosis of moderate to severe persistent allergic asthma confirmed by appropriate diagnostic testing • Greater than or equal to 6 years of age • Has a positive skin test or in vitro reactivity to a perennial aeroallergen • Has inadequate control of symptoms after 3 months of consecutive treatment with the following o High-dose corticosteroid o Long-acting beta agonist or leukotriene inhibitors • Age 12 years and over: Has baseline serum total Immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels between 30 Units/mL and 700 Units/mL • Age 6 years to less than 12 years: Has baseline serum total Immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels between 30 Units/mL and up to 1300 Units/mL • Has a body weight that is 150 kg or less • Is not concurrently taking Cinqair, Nucala, or Fasenra V1.0.2019 - Effective 1/1/2019 © 2019 eviCore healthcare. -

Monitoring of Occupational and Environmental Aeroallergens – EAACI Position Paper

POSITION PAPER Monitoring of occupational and environmental aeroallergens – EAACI Position Paper Concerted action of the EAACI IG Occupational Allergy and Aerobiology & Air Pollution M. Raulf1, J. Buters2, M. Chapman3, L. Cecchi4, F. de Blay5, G. Doekes6, W. Eduard7, D. Heederik6, M. F. Jeebhay8, S. Kespohl1,E.Krop6, G. Moscato9, G. Pala10, S. Quirce11, I. Sander1, V. Schlunssen€ 12, T. Sigsgaard12, J. Walusiak-Skorupa13, M. Wiszniewska13, I. M. Wouters6 & I. Annesi-Maesano14,15 1Institute for Prevention and Occupational Medicine of the German Social Accident Insurance, Ruhr-Universitat€ Bochum (IPA), Bochum; 2ZAUM- Center of Allergy & Environment, Helmholtz Zentrum Munchen/Technical€ Universitat€ Munchen,€ Christine Kuhne€ Center for Allergy Research and Education (CK-CARE), Member of the German Center of Lung Research (DZL), Munich, Germany; 3Indoor Biotechnologies Ltd, Cardiff, UK; 4Interdepartmental Centre of Bioclimatology, University of Florence, Allergy and Clinical Immunology Section, Azienda Sanitaria di Prato, Prato, Italy; 5Department of Chest Diseases, University Hospital Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France; 6Division of Environmental Epidemiology, Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences (IRAS), Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands; 7Department of Chemical and Biological Work Environment/National Institute of Occupational Health, Institute of Medical Biology, University in Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway; 8Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health Research, School of Public Health and Family Medicine, University of Cape Town, -

Respiratory Food Allergy

Respiratory Food Allergy Elham Hossny, MD, PhD, FAAAAI Head, Pediatric Allergy and Immunology Unit, Children’s Hospital, Ain Shams University Conflicts of Interest Nothing to disclose • There is clinical evidence that food allergy plays a role in the pathogenesis of respiratory disorders • This seems to be more common in infants and young children than adults CONTENT • Causative food allergens • Respiratory manifestations of food allergy • Indications of screening for food allergy • Key notes and unmet needs Causative Food Allergens Class I food allergens: Milk, egg, seafood, peanut, tree nuts, wheat, and soy (most common) Class II food allergens: Fruits and vegetables (food-pollen syndrome) • Cow's milk is one of the first foreign proteins ingested by infants and is one of the most common and potent food allergens. • Contamination of probiotic preparations with milk allergens can cause anaphylaxis in children with cow's milk allergy. Causative food allergens (Cont’d) The presence of egg allergy in infancy especially when coexisting with eczema increases the likelihood of respiratory allergy and aeroallergen sensitization in early childhood. Tariq SM, et al. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2000;11:162-7. Food Pollen Syndrome = Oral Allergy Syndrome • Cross-reactive allergens between certain foods and airborne pollens • The most famous cross reacting allergen is profillin Birch pollen – almonds – apples – apricots – carrots – celery – cherries – kiwifruit – parsley – peaches – pears – peppers – plums – potatoes – prunes Food Pollen Syndrome (Cont’d) Grass pollen – Melons – Tomatoes – Oranges Ragweed pollen – Banana – Cantaloupe – Watermelon – Cucumber – Zucchini 0-5 6-10 11-15 Pollen food syndrome amongst children with seasonal allergic rhinitis attending allergy clinic Ludman S, et al. -

PDF Full-Text

50 Z. Caliskaner et al. Original Article Skin test positivity to aeroallergens in the patients with chronic urticaria without allergic respiratory disease Z. Caliskaner1, S. Ozturk1, M. Turan2, M. Karaayvaz1 Gülhane Military Medical Academy and Medical Faculty, 1 Department Allergy and 2 Department of Hydroclimatology and Medical Ecology, Ankara, Türkiye (www.gata.edu.tr/dahilibilimler/allerji/index.htm) Summary. The etiology of chronic urticaria and angioedema remains uncertain in most of the patients. There are several agents and factors including medications, foods and food additives, infections, contactants, inhalants, physical factors and autoimmunity that implicated in provoking urticaria symptoms. In addition, the possible role of house dust mites has been considered in a few reports. We investigated skin test positivity to house dust mites and other inhalants in 259 patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria and angioedema but without allergic rhinitis and/or asthma. Results were compared with both 300 healthy controls and 300 atopic patients. Immediate cutaneous reactivity to one or more allergens was detected in 71 patients in the study group (27.4 %). The most common allergens were house dust mites (24.7 %). Skin prick test sensitivity to other inhalant allergens including pollens, molds and cockroach were 7.7 %, 0.4 % and 0.8 %, respectively. In the healthy control group 7 % of patients were found as atopic with respect to skin prick test results. The most common allergens in healthy controls were pollens (6 %), and house dust mites (4.7 %). In atopic control group, pollens and mites are also the most common allergens detected in skin prick test (62 % and 50.3 %, respectively). -

European Standards and North American Practice Parameters for Skin Prick Testing Panels in Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma

Romanian Journal of Rhinology, Vol. 5, No. 17, January-March 2015 DOI: 10.1515/rjr-2015-0002 LITERATURE REVIEW European standards and North American practice parameters for skin prick testing panels in allergic rhinitis and asthma Florin-Dan Popescu Department of Allergology, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania ABSTRACT According to the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA²LEN), a pan-European skin prick test panel for the diag- nosis of allergic rhinitis and asthma includes 18 aeroallergen extracts, supplemented if necessary for regional or for particular patient needs, while the Allergen Subcommittee and Immunotherapy Committee of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) selected 36 major clinically relevant aeroallergens for North America. KEYWORDS: aeroallergen extracts, skin prick tests, allergic rhinitis and asthma INTRODUCTION PARAMETERS FOR SKIN PRICK TESTING PANELS Skin prick testing is an important reliable method to diagnose IgE-mediated allergic rhinitis, rhinocon- The aeroallergen extracts included in the Euro- junctivitis and asthma. This widely used in vivo assess- pean standards and North American practice param- ment, indicated, performed and interpreted by al- eters skin prick panels are of plant, fungal and ani- lergy practitioners, is minimally invasive, has immedi- mal origins, as described below1-8. ately available and reproducible results, and provides Aeroallergen extracts of animal origin included in evidence for aeroallergen sensitization. Skin prick these standards belong to Arthropoda phylum, Astig- tests are highly specific and sensitive for the diagnosis mata order (house dust mites from the Pyroglyphidae of respiratory allergies. The positive predictive value family), Blattodea order (Ectobiidea family from the to diagnose allergic rhinitis increases to 97-99% if al- Insecta class), and Carnivora order pet animals (Felidae lergy skin prick testing is utilized1,2. -

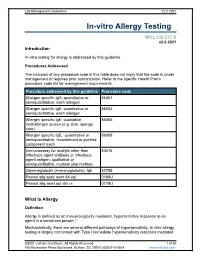

In-Vitro Allergy Testing

Lab Management Guidelines V2.0.2021 In-vitro Allergy Testing MOL.CS.317.X v2.0.2021 Introduction In-vitro testing for allergy is addressed by this guideline. Procedures Addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedure addressed by this guideline Procedure code Allergen specific IgG; quantitative or 86001 semiquantitative, each allergen Allergen specific IgE; quantitative or 86003 semiquantitative, each allergen Allergen specific IgE; qualitative, 86005 multiallergen screen (e.g. disk, sponge, card) Allergen specific IgE; quantitative or 86008 semiquantitative, recombinant or purified component each Immunoassay for analyte other than 83516 infectious agent antibody or infectious agent antigen; qualitative or semiquantitative, multiple step method Gammaglobulin (immunoglobulin); IgE 82785 Peanut allg spec asmt 64 epi 0165U Peanut allg asmt epi clin rx 0178U What Is Allergy Definition Allergy is defined as an immunologically mediated, hypersensitive response to an agent in a sensitized person.1-7 Mechanistically, there are several different pathways of hypersensitivity. In vitro allergy testing is largely concerned with Type I immediate hypersensitivity reactions mediated ©2021 eviCore healthcare. All Rights Reserved. 1 of 30 400 Buckwalter Place Boulevard, Bluffton, SC 29910 (800) 918-8924 www.eviCore.com Lab Management Guidelines V2.0.2021 by IgE.8 These -

Inquiry Into Allergies and Anaphylaxis

Inquiry into allergies and anaphylaxis The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care and Sport. This submission addresses two of the specific terms of reference (number 4 and 5) for this parliamentary inquiry. 4. Access to and cost of services, including diagnosis, testing, management, treatment and support; Current knowledge and practice Diagnosis for allergy relies on clinical history and evidence of allergen-specific sensitisation. Allergic sensitisation is usually measured with a skin prick test requiring training and consistency of practice. Skin prick test accuracy has a dependence on quality of allergen extracts. This method is performed by nurses or doctors in clinical immunology specialist or hospital outpatient clinics limiting access for patients in rural and remote areas. It requires patients to withdraw anti-histamine treatment for three days prior to testing. Allergen sensitisation can also be measured by immunopathology tests reported as concentrations of specific IgE. Whole blood basophil activation tests can be performed in a specialised immunopathology setting but this is not routinely offered and is time dependent in terms of duration since the blood was sampled and time since the anaphylactic event occurred. Most of allergen sensitisation tests are based on aqueous extracts of whole allergen sources. The extracts contain a mixture of allergenic and not allergenic material. As complex biological sources, the content of allergen and non-allergenic matter within aqueous extracts will vary from batch to batch affecting the consistency and efficacy of products for diagnosis and allergen-specific immunotherapy. Over 100 standardized allergen component resolved diagnostic tests for common food, animal dander and aeroallergen sources are available as single point high-throughput testing and/or multi-allergen arrays by pathology services. -

A Descriptive Study on Aeroallergen Sensitivity Pattern in Children With

Published online: 2020-07-20 THIEME e48 Original Article A Descriptive Study on Aeroallergen Sensitivity PatterninChildrenwithBronchialAsthma and/or Allergic Rhinitis Saket Yadav1 Madhu Mathur1 Gunjan Agarwal1 Abhishek Kumar Sharma1 1 Department of Pediatrics, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College & Address for correspondence Abhishek Kumar Sharma, DCH, DNB, Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India Department of Pediatrics, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College & Hospital, Sitapura, Jaipur 302022, Rajasthan, India J Child Sci 2020;10:e48–e52. (e-mail: [email protected]). Abstract Background The growing prevalence of allergy and asthma in India has become a major health concern, with symptoms ranging from mild rhinitis to severe asthma, and aeroallergens play a major role in the pathogenesis of reactive airway diseases. The distribution of aeroallergen and the knowledge of allergen sensitivity pattern in northern India (Rajasthan) are limited. The aim of our study was to determine the prevalence of various aeroallergens in children with bronchial asthma and/or allergic rhinitis by skin prick test at a tertiary care center in Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. Methods Children who had presented to the Department of Pediatrics (outpatient department and inpatient department), Mahatma Gandhi Medical College, Jaipur, from January 2018 to June 2019 fulfilling the inclusion criteria, were included in this prospective study. A total of 15 antigens were used. Skin prick testing was performed as per standard protocol. Keywords Result Among total 60 children with respiratory allergic diseases, overall the highest ► reactive airway percentage of skin prick test positivity was found among house dust mite (66.6%), diseases storage mite (41.6%), wheat (33.3%), animal dander (30%), and Kentucky bluegrass ► skin prick test (26.6%), in that order. -

Laboratory Diagnosis of Allergy

Laboratory diagnosis of allergy Clinically relevant and cost-effective test selection Allergic disorders result from an inappropriate, usually IgE-mediated, immune response upon exposure to environmental, food, insect or medication allergens. Common clinical manifestations of allergy include rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma, eczema, acute urticaria and anaphylaxis. Disorders, such as chronic urticaria, hereditary angioedema and T-cell contact dermatitis, while clinically similar to allergy in some ways, are not IgE-mediated. Testing for allergy Most tests for allergy are laboratory tests for allergic sensitisation or the presence of allergen-specific IgE. An individual who experiences symptoms when exposed to an allergen will usually have measurable IgE which specifically recognises that allergen. Testing allergen-specific IgE has fundamental importance for the diagnosis of allergic disorders. Skin testing is the in vivo equivalent to allergen-specific IgE testing and has advantages, such as providing immediate results and being less expensive. However, it carries the risk of allergic reaction (including anaphylaxis), and results may be affected by antihistamines, dermographism and a narrower range of allergens being available, when compared to laboratory tests. Regardless of the method used, the demonstration of sensitisation is not sufficient to diagnose allergy. Some sensitised individuals remain symptom-free after exposure and others, who react to an allergen, may not have any detectable allergen- specific IgE in their blood. Therefore, the results of allergy testing must be interpreted in the context of the patient’s clinical history; an allergy diagnosis cannot be made solely on the results of laboratory or skin testing. Types of laboratory tests for allergy Total IgE Allergen-specific IgE Patients with allergic conditions, such as asthma, allergic Allergen-specific IgE detection (often referred to as RAST, a rhinitis or atopic dermatitis, often have higher serum levels specific methodology which has been superseded) is most of IgE than the general population.