Mary Regional Resilience Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

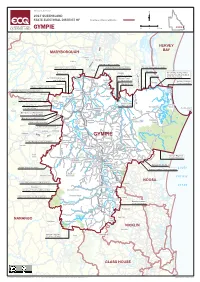

GYMPIE GYMPIE 0 5 10 Km

Electoral Act 1992 N 2017 QUEENSLAND STATE ELECTORAL DISTRICT OF Boundary of Electoral District GYMPIE GYMPIE 0 5 10 km HERVEY Y W H BAY MARYBOROUGH Pioneers Rest Owanyilla St Mary E C U Bauple locality boundary R Netherby locality boundary B Talegalla Weir locality boundary Tin Can Bay locality boundary Tiaro Mosquito Ck Barong Creek T Neerdie M Tin Can Bay locality meets in A a n locality boundary R Tinnanbar locality and Great r a e Y Kauri Ck Riv Sandy Strait locality Lot 125 SP205635 and B Toolara Forest O Netherby Lot 19 LX1269 Talegalla locality boundary R O Gympie Regional Weir U Tinnabar Council boundary Mount Urah Big Sandy Ck G H H Munna Creek locality boundary Bauple y r a T i n Inskip M Gundiah Gympie Regional Council boundary C r C Point C D C R e a Caloga e n Marodian k Gootchie O B Munna Creek Bauple Forest O Glenbar a L y NP Paterson O Glen Echo locality boundary A O Glen Echo G L Grongah O A O NP L Toolara Forest Lot 1 L371017 O Rainbow O locality boundary W Kanyan Tin Can Bay Beach Glenwood Double Island Lot 648 LX2014 Kanigan Tansey R Point Miva Neerdie D Wallu Glen Echo locality boundary Theebine Lot 85 LX604 E L UP Glen Echo locality boundary A RD B B B R Scotchy R Gunalda Cooloola U U Toolara Forest C Miva locality boundary Sexton Pocket C Cove E E Anderleigh Y Mudlo NP A Sexton locality boundary Kadina B Oakview Woolooga Cooloola M Kilkivan a WI r Curra DE Y HW y BA Y GYMPIE CAN Great Sandy NP Goomboorian Y A IN Lower Wonga locality boundary Lower Wonga Bells Corella T W Cinnabar Bridge Tamaree HW G Oakview G Y -

Gympie Region Canoe and Kayak Launch Points

About the Mary River Gympie Region Canoe and Kayak Launch Points The Mary River is a major river system, traversing through the Sunshine Coast and Explore the Gympie region from our numerous Wide Bay-Burnett regions. Rich in picturesque waterways including the picturesque Mary River, green scenery and abundant with unique one of Queensland’s natural jewels. Start your wildlife, the Mary River and its tributaries are journey from Gympie Regional Council’s canoe CANOE AND KAYAK the perfect place for canoe and kayak and kayak launch points. enthusiasts to paddle and explore. Get up close with the rare Mary River Cod, www.gympie.qld.gov.au/canoe-and-kayak Australian Lungfish, platypus and Mary River Turtle, or stop along the way for a picnic on one of the grassy banks in our beautiful parks. There are plenty of tributaries along the way, so beginner and intermediate paddlers can set a slower pace on their journey. Experienced kayakers may wish to set themselves a more challenging course. Gympie is perfectly positioned for nature enthusiasts and paddlers to enjoy the watercourses of this region, both from the banks and the water. About the launch points Enjoy the waterways of the Gympie region and paddle the Mary River and its tributaries from six launch points in Gympie, Imbil and Kandanga. Designated off-street parking areas are available at all locations. GYMPIE LAUNCH POINTS Launch points in Gympie can be accessed via Attie Sullivan Park (adjacent to the Normanby Bridge on Mary Valley Road) and the Gympie Weir, (near Kidd Bridge on River Terrace). -

April 2019 No

April 2019 No. 92 I.S.S.N. 1035-3534 Gympie Gazette Gympie Gazette April 2019 Contents: Society Snippets. 4-5 When William met Jessie: 6-7 Land Records: 8 ‘Wingie the Railway Cop”: 9-10 Returning the Medals: 11-13 My Life in a Nutshell: 14-15 Never Give Up: 16 O’Connor-M’Mahon Wedding: 18 EDITORIAL: Welcome to the first edition of Gympie Gazette for 2019. Our President, Margaret Long has been ‘missing in action for several weeks with a persistent leg problem, necessitating a few days in hospital. The ‘back room’ is not the same without her and we all wish her full return to good health. Early in the year we were very sorry to receive the resignation of Di Grambower from the position of librarian. Her resignation was accepted with much regret. We look forward to seeing our new Gympie Family History Society Inc. signs erected. Together with re-furbished gardens, beautifully maintained by Clem, no one will be able to say that they don’t know where we are. Have you checked out our GFHS Facebook page, ably administered by Conny, Denise and Di W. In this edition of Gympie Gazette, we have given you plenty of variety, with articles ranging from a WW1 love story, a railway story and two happy ending research stories. Remember that we welcome any contributions. Our magazine is only as interesting as contributions from you, the members will make it. Enjoy your read. Val Thomas and Val Buchanan. Vice Presidents Report. (For April 2019 meeting) Hello everyone. -

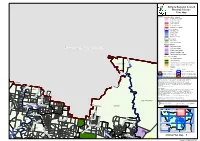

Gympie Regional Council Planning Scheme Zone Map Zoning Plan Map 4

Gympie Regional Council Planning Scheme Zone Map ZONES Residential zones category Character Residential Residential Living Rural Residential Residential Choice Tourist Accommodation Centre zones category Principal Centre District Centre Local Centre Specialised Centre Recreation category Open Space Sport and Recreation Industry category High Impact Industry Fraser Coast Regional Council Low Impact Industry Medium Impact Industry Industry Investigation area Waterfront and Marine Industry B I G Other zones category S A N Community Purposes D Y C Extractive Industry R E E K Environmental Management and Conservation TUAN FOREST Limited Development (Constrained Land) Township Rural Road TINA N Proposed Highway Zone Precinct Boundary A C ! ! R ! E ! EK DCDB ver. 05 June 2012 ! Suburb or Locality Boundary Waterbodies & Waterways Local Government Boundary Disclaimer While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this map, Gympie Regional Council makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation, MUNNA CREEK MUNNA CREEK liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damage (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs which might incur as a result of the data being inaccurate or incomplete in any way and D A K for any reason. O E R E © Copyright Gympie Regional Council 2012 C R S ULIRRAH EY L D Cadastre Disclaimer: L A U THEEBINE Despite Department of Environment and Resource Management (DERM)'s best efforts,DERM makes no A O representations or warranties in relation to the Information, and, to the extent permitted by law, C R exclude or limit all warranties relating to correctness, accuracy, reliability, completeness or currency E I and all liability for any direct, indirect and consequential costs, losses, damages and expenses incurred P in any way (including but not limited to that arising from negligence) in connection with any use of or M Y reliance on the Information. -

Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 by Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane

ARCHIVE: Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 By Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane The date of the cyclone refers to the day of landfall or the day of the major impact if it is not a cyclone making landfall from the Coral Sea. The first number after the date is the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) for that month followed by the three month running mean of the SOI centred on that month. This is followed by information on the equatorial eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures where: W means a warm episode i.e. sea surface temperature (SST) was above normal; C means a cool episode and Av means average SST Date Impact January 1858 From the Sydney Morning Herald 26/2/1866: an article featuring a cruise inside the Barrier Reef describes an expedition’s stay at Green Island near Cairns. “The wind throughout our stay was principally from the south-east, but in January we had two or three hard blows from the N to NW with rain; one gale uprooted some of the trees and wrung the heads off others. The sea also rose one night very high, nearly covering the island, leaving but a small spot of about twenty feet square free of water.” Middle to late Feb A tropical cyclone (TC) brought damaging winds and seas to region between Rockhampton and 1863 Hervey Bay. Houses unroofed in several centres with many trees blown down. Ketch driven onto rocks near Rockhampton. Severe erosion along shores of Hervey Bay with 10 metres lost to sea along a 32 km stretch of the coast. -

Restricted Water Ski Areas in Queensland

Restricted Water Ski areas in Queensland Watercourse Date of Gazettal Any person operating a ship towing anyone by a line attached to the ship (including for example a person water skiing or riding on a toboggan or tube) within the waters listed below endangers marine safety. Brisbane River 20/10/2006 South Brisbane and Town Reaches of the Brisbane River between the Merivale Bridge and the Story Bridge. Burdekin River, Charters Towers 13/09/2019 All waters of The Weir on the Burdekin River, Charters Towers. Except: • commencing at a point on the waterline of the eastern bank of the Burdekin River nearest to location 19°55.279’S, 146°16.639’E, • then generally southerly along the waterline of the eastern bank to a point nearest to location 19°56.530’S, 146°17.276’E, • then westerly across Burdekin River to a point on the waterline of the western bank nearest to location 19°56.600’S, 146°17.164’E, • then generally northerly along the waterline of the western bank to a point on the waterline nearest to location 19°55.280’S, 146°16.525’E, • then easterly across the Burdekin River to the point of commencement. As shown on the map S8sp-73 prepared by Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ) which can be found on the MSQ website at www.msq.qld.gov.au/s8sp73map and is held at MSQ’s Townsville Office. Burrum River .12/07/1996 The waters of the Burrum River within 200 metres north from the High Water mark of the southern river bank and commencing at a point 50 metres downstream of the public boat ramp off Burrum Heads Road to a point 200 metres upstream of the upstream boundary of Lions Park, Burrum Heads. -

Gympie Regional Council Planning Scheme Zone

AD RO T KE C O P Y H H C T E R O M C S A N S R O ADB R NEERDIE O SA J HN N SO U D N Y R C O C AD E R Gympie Regional Council GUNALDA E H E SCOTCHY POCKET K KIA ORA I C G ANDERLEIGH A D Planning Scheme RMY H LE A D RO W OSA O A A TOOLARA FOREST R E D R Zone Map IN X Y Y A T CUR T O E R 1 A C N N L R EEK 0 U L B T P I O R U R DOWNSFIELD H N ZONES Residential zones category O O EN A M CA P RY RO IL A O AD N Character Residential V D S A E ED D SEXTON HW W R Residential Living EB D O AY STE ROA D BY R A A PA D O Rural Residential D SS R A ES O H LI Residential Choice R CURRA A IL S RV G E H E AY Y O H D M Tourist Accommodation SI D ROSS PHAN RO A O D A U ROA AD I O D E P L O N R L T Centre zones category IAN G I DRIVE E G N S R UR S R R DB Principal Centre C S L C S O O R U E G G A AR W R E I R N D D District Centre DE B WOOD ROA N E GOOMBOORIAN AY HIG O D E R ROAD HWA R O K Y A D 44 A J A A R Local Centre F D O D A O C WI E IF R DE S D A O BA L O O U Specialised Centre Y T C O R D N H A W YOUNG ROSS CREEK T W IG T T E OONGA K H E A R Recreation category CR E E W R G R I O A O G Open Space Y CORELLA A J A NORTH DEEP CREEK A D D N AD E 4 R Sport and Recreation PHILLIPS RO N 4 O SE A AD N HALGH Industry category R EN R O AD O RE LOWER WONGA D D High Impact Industry A AD G A A O D ID R O S R D E O E R M Low Impact Industry A R R O O WILSONS POCKET N Medium Impact Industry BELLS BRIDGE VETERAN D HAR R D VEY O ROA D A A D L T A E RO RO O Industry Investigation area E R E CHATSWORTH OAD AR EK R B D O R M A T TA E T T R A Waterfront and Marine Industry -

Street Tree Master Plan Report © Sunshine Coast Regional Council 2009-Current

Sunshine Coast Street Tree Master Plan 2018 Part A: Street Tree Master Plan Report © Sunshine Coast Regional Council 2009-current. Sunshine Coast Council™ is a registered trademark of Sunshine Coast Regional Council. www.sunshinecoast.qld.gov.au [email protected] T 07 5475 7272 F 07 5475 7277 Locked Bag 72 Sunshine Coast Mail Centre Qld 4560 Acknowledgements Council wishes to thank all contributors and stakeholders involved in the development of this document. Disclaimer Information contained in this document is based on available information at the time of writing. All figures and diagrams are indicative only and should be referred to as such. While the Sunshine Coast Regional Council has exercised reasonable care in preparing this document it does not warrant or represent that it is accurate or complete. Council or its officers accept no responsibility for any loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from acting in reliance upon any material contained in this document. Foreword Here on our healthy, smart, creative Sunshine Coast we are blessed with a wonderful environment. It is central to our way of life and a major reason why our 320,000 residents choose to live here – and why we are joined by millions of visitors each year. Although our region is experiencing significant population growth, we are dedicated to not only keeping but enhancing the outstanding characteristics that make this such a special place in the world. Our trees are the lungs of the Sunshine Coast and I am delighted that council has endorsed this master plan to increase the number of street trees across our region to balance our built environment. -

Mary River Catchment Crawl 4 and 5 October 2016

Mary River Catchment Crawl 4th and 5th October 2016 Catchment crawl participants: Brad Wedlock, Caitlin Mill, Tanzi Smith, Jess Dean, Shaun Fisher, Ian Mackay, Ruth Hutchison, Matt Tattam, Kevin Jackson Introduction During the Mary River Month celebrations, the Mary River Catchment Coordinating Committee once again conducted its 8th annual Catchment Crawl on October 4th and 5th, 2016. The Catchment Crawls are designed to provide a snapshot of water quality along the Mary River. Water quality parameters are measured in an effort to gain insight to trends associated with cumulative effects and any other changes along the catchment area. On day one, testing begins in the upper reaches of the catchment, followed by a second day of testing in the lower reaches of the river and its tributaries, right out to the river mouth. A total of 14 freshwater sites were sampled along the main trunk of the Mary River, along with seven sites in several upper and lower tributaries for a total of 21 sites. The tributaries sampled include Six Mile Creek, Widgee Creek, Wide Bay Creek, Munna Creek and Tinana Creek. Sampling occurred across all three local government areas in the catchment. Figure 1 shows a map of all sites sampled during the 2016 catchment crawl. Creek junctions with the Mary River were targeted for sampling in order to gather information on the effects of tributaries flowing into the river. At each sampling site, a standard water test encompassing temperature, dissolved oxygen, electrical conductivity, pH and turbidity was performed. In addition, a sample was taken at each site in accordance with DSITI protocol to be tested for nutrients and total suspended solids. -

Wambaliman SPRING 2017

The newsletter of the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland Fraser Coast Branch SPRING 2017 Wambaliman since 1967 In the language of the Butchulla people, who are custodians of land that includes the Fraser Coast, ‘wambaliman’ means ‘to carry’, and refers to the messages that the Newsletter is communicating. Editor's Note One of the things that took up some precious time in the preparation period of this issue of Wambaliman was a trip to Mt Larcom for the WILDLIFE PRESERVATION Central Branches Get-together. It was an in- SOCIETY OF QUEENSLAND spiring weekend of discussion and sociability with intelligent and motivated people with wild- known informally as life conservation in their blood. WILDLIFE QUEENSLAND One of the items on the program was Branch Reports, from which it was clear that we all FRASER COAST BRANCH face similar challenges in wildlife conservation. PO Box 7396 Urangan, 4655 One distinct difference between the other Branches and Fraser Coast Branch was that we President: are positively active. Audrey Sorensen This issue of the newsletter doesn’t really do 4125 6891 [email protected] justice to all the positive activities that our Vice President: Branch is involved in, or the efforts of all the people that are driving those activities. Rodney Jones 0423 812 881 A read through our parting President Peter Secretary: Duck’s report and the Branch Activity report Vanessa Elwell-Gavins only skims the surface of all the action. Many 0428 624 366 of our members are fully engaged in the list of Assistant Secretary: activities mentioned in the CEP report. -

Gympie Regional Council Planning Scheme Zone Map Zoning Plan

D A T O A R N D K U E R E R T C R A O V C I E L S A T C O G N NO IB TRAVESTON O L R SA S K EH DO R O MA A O DAGUN E N R O A AD N N D J AMAMOOR MA R N E DAGUN ROAD R D D O A R O O M A R SIX A R D N M C Y A O IL E CREEK O G T C D S Gympie Regional Council R I E L R V N D KYBONG A N L OA E TR A C R E M E MOOLOO E R T K Planning Scheme STEG E O E HC R TRAVESTON K AT O UPPER GLASTONBURY E LANGSHAW A Zone Map RO H D AD AMAMOOR CREEK K ZONES Residential zones category EE R C L Character Residential M CGIL CREEK MAMOOR COLES CREEK A EDWARDS ROAD COLES EK Residential Living CBR E R AM U Rural Residential A AMAMOOR GO MO O C OR M E C O H Residential Choice REEK ROA D N D G I A G R SK O YRIH K Tourist Accommodation O NG C EE R AD W R D A Centre zones category L Y E D 1 Principal Centre KEL I ROA 0 L F PE A Y ROA HASTHOR D D District Centre N H O Local Centre A M KANDANGA P A P I Specialised Centre Y D AMAMOOR CREEK V A E KRESS ROAD Recreation category KANDANGAL CREEK RN L S EY T Open Space RO R TUCHEKOI A O Sport and Recreation D A EK D K ROAD A CRE EE NG TT ROAD ND ANS CR Industry category A PI O I RO CHINAM EEK D W AD R CR N A CREEK D A High Impact Industry OO A NG ROA MELAWONDIL AM K DA E S H AM N M O U T KA REEK Low Impact Industry BA C Y AB 3 Medium Impact Industry D 8 D A 4 A NE CREE UPPER KANDANGA RO O IRONSTO K L D R RO Industry Investigation area I R A E A E D O K N T V N O U K I Waterfront and Marine Industry E HE R T U R C Y N R O I Other zones category A L M HA O W RT ROAD L Community Purposes DA O N NG M O A A CREEK K IT R C O T Extractive Industry IMBIL H B R E A H L L K B L LA EE S R CR E CARTERS RIDGE Environmental Management and Conservation C D A I K R R BB Y E O A P BOLLIER E AD Y R Limited Development (Constrained Land) K M IN R Y G O AD A D G R RO C Township A I B YA NT D O M R R B E K E Rural Road E I E L K CR B RO A R W Proposed Highway Zone Precinct Boundary B O H A ! ! B O E D A L L ! Y A ! BELLA CREEK O N DCDB ver. -

Beacon to Beacon Guide: Noosa River

Maritime Safety Queensland Noosa River Boat Ramp, Tewantin Beacon to Beacon Guide Noosa River Published by For commercial use terms and conditions Maritime Safety Queensland Please visit the Maritime Safety Queensland website at www.msq.qld.gov.au © Copyright The State of Queensland (Department of Transport and Main Roads) 2021 ‘How to’ use this guide Use this Beacon to Beacon Guide with To view a copy of this licence, visit the ‘How to’ and legend booklet available from https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.msq.qld.gov.au Noosa River Cooloola Beach Key Sheet Next series NOOSA Great Sandy Strait RIVER Marine rescue services 10 CG Noosa Enlargements A Boreen Point B Noosa Marina Lake Cooloola Shark control apparatus Lake exclusion zones Como Exclusion zones exist for waters within 20 metres of any shark control apparatus. It is an offence (fines may apply) to be in an exclusion zone if not transiting directly through. For further information see the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries website at www.daf.qld.gov.au. Teewah Beach Depth contour date information Elanda Point Depth contours shown on the maps within this guide were surveyed by Maritime Safety Queensland 2000-2016. Kin Kin Some 0m contours have been approximated from recent Lake Teewah Cootharaba TMR air photography. A Boreen Point SOUTH CORAL NOOSA SEA RIVER PACIFIC Lake Cooroibah Six Mile Creek Dam Noosa Head TEWANTIN 10 Lake 10 Macdonald B NOOSA HEADS OCEAN Sunshine Cooroy Beach For maps and information on the Noosa River marine zones please visit Maritime Safety Queensland website (www.msq.qld.gov.au) under the Waterways tab and click on Marine Zones.