Download This Excerpt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chic Street Oscar De La Renta Addressed Potential Future-Heads-Of-States, Estate Ladies and Grand Ole Party Gals with His Collection of Posh Powerwear

JANET BROWN STORE MAY CLOSE/15 ANITA RODDICK DIES/18 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’TUESDAY Daily Newspaper • September 11, 2007 • $2.00 Ready-to-Wear/Textiles Chic Street Oscar de la Renta addressed potential future-heads-of-states, estate ladies and grand ole party gals with his collection of posh powerwear. Here, he showed polish with an edge in a zip-up leather top and silk satin skirt, topped with a feather bonnet. For more on the shows, see pages 6 to 13. To Hype or Not to Hype: Designer Divide Grows Over Role of N.Y. Shows By Rosemary Feitelberg and Marc Karimzadeh NEW YORK — Circus or salon — which does the fashion industry want? The growing divide between designers who choose to show in the commercially driven atmosphere of the Bryant Park tents of Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week and those who go off-site to edgier, loftier or far-flung venues is defining this New York season, and designers on both sides of the fence argue theirs is the best way. As reported, IMG Fashion, which owns Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week, has signed a deal to keep those shows See The Show, Page14 PHOTO BY GIOVANNI GIANNONI GIOVANNI PHOTO BY 2 WWD, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2007 WWD.COM Iconix, Burberry Resolve Dispute urberry Group plc and Iconix Brand Group said Monday that they amicably resolved pending WWDTUESDAY Blitigation. No details of the settlement were disclosed. Ready-to-Wear/Textiles Burberry fi led a lawsuit in Manhattan federal court on Aug. 24 against Iconix alleging that the redesigned London Fog brand infringed on its Burberry check design. -

Paul Iribe (1883–1935) Was Born in Angoulême, France

4/11/2019 Bloomsbury Fashion Central - BLOOMSBURY~ Sign In: University of North Texas Personal FASHION CENTRAL ~ No Account? Sign Up About Browse Timelines Store Search Databases Advanced search --------The Berg Companion to Fashion eBook Valerie Steele (ed) Berg Fashion Library IRIBE, PAUL Michelle Tolini Finamore Pages: 429–430 Paul Iribe (1883–1935) was born in Angoulême, France. He started his career in illustration and design as a newspaper typographer and magazine illustrator at numerous Parisian journals and daily papers, including Le temps and Le rire. In 1906 Iribe collaborated with a number of avantgarde artists to create the satirical journal Le témoin, and his illustrations in this journal attracted the attention of the fashion designer Paul Poiret. Poiret commissioned Iribe to illustrate his first major dress collection in a 1908 portfolio entitled Les robes de Paul Poiret racontées par Paul Iribe . This limited edition publication (250 copies) was innovative in its use of vivid fauvist colors and the simplified lines and flattened planes of Japanese prints. To create the plates, Iribe utilized a hand coloring process called pochoir, in which bronze or zinc stencils are used to build up layers of color gradually. This publication, and others that followed, anticipated a revival of the fashion plate in a modernist style to reflect a newer, more streamlined fashionable silhouette. In 1911 the couturier Jeanne Paquin also hired Iribe , along with the illustrators Georges Lepape and Georges Barbier, to create a similar portfolio of her designs, entitled L’Eventail et la fourrure chez Paquin. Throughout the 1910s Iribe became further involved in fashion and added design for theater, interiors, and jewelry to his repertoire. -

Issue: Fashion Industry Fashion Industry

Issue: Fashion Industry Fashion Industry By: Vickie Elmer Pub. Date: January 16, 2017 Access Date: October 1, 2021 DOI: 10.1177/237455680302.n1 Source URL: http://businessresearcher.sagepub.com/sbr-1863-101702-2766972/20170116/fashion-industry ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Can it adapt to changing times? Executive Summary The global fashion business is going through a period of intense change and competition, with disruption coming in many colors: global online marketplaces, slower growth, more startups and consumers who now seem bored by what once excited them. Many U.S. shoppers have grown tired of buying Prada and Chanel suits and prefer to spend their money on experiences rather than clothes. Questions about fashion companies’ labor and environmental practices are leading to new policies, although some critics remain unconvinced. Fashion still relies on creativity, innovation and consumer attention, some of which comes from technology and some from celebrities. Here are some key takeaways: High-fashion brands must now compete with “fast fashion,” apparel sold on eBay and vintage sites. Risk factors for fashion companies include China’s growth slowdown, reduced global trade, Brexit, terrorist attacks and erratic commodity prices. Plus-size women are a growing segment of the market, yet critics say designers are ignoring them. Overview José Neves launched Farfetch during the global economic crisis of 2008, drawing more on his background in IT and software than a love of fashion. His idea: Allow small designers and fashion shops to sell their wares worldwide on a single online marketplace. The site will “fetch” fashion from far-off places. -

Retail Product Merchandising: Retail Buying-Selling Cycle

Retail Product Merchandising: Retail Buying-Selling Cycle SECTION 2: Establishing the Retail Merchandise Mix Part 1: The Basics of the Retail Merchandise Mix Part 1: 1-2 Industry Zones in the Apparel Industry Fashion products, especially in the women’s wear industry, are categorized by the industry zone in which they are produced and marketed. Industry has designated these zones as a) Haute Couture or couture, b) designer, c) bridge, d) contemporary, e) better, f) moderate, g) popular price/budget/mass, and g) discount/off price. Often the industry emphasizes the wholesale costs or price points of the merchandise in order to define the zone. However, price alone is not the major factor impacting the placement of the merchandise in the zone. Major factors impacting the zone classifications include the following criteria: . fashion level of the design (i.e., degree of design innovation inherent or intrinsic to the merchandise) . type and name of designer creating and developing the design concept . wholesale cost and retail price of product . types and quality of fibers and fineness of fabrications, trims, and findings . standards of construction quality or workmanship quality. In summary, the classification of a zone is based on the type of designer creating the product, design level of the product, type and quality of fabrications, standards of the workmanship, and the price range of the merchandise. Therefore, depending upon the lifestyle of the target consumer, the fashion taste level of that consumer (i.e., position of product on the fashion curve), and the current fashion trend direction in the market, the retailer, when procuring the merchandise mix, selects the industry zone(s) which offer(s) the product characteristics most desired by the target consumer. -

Fashion Awards Preview

WWD A SUPPLEMENT TO WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY 2011 CFDA FASHION AWARDS PREVIEW 053111.CFDA.001.Cover.a;4.indd 1 5/23/11 12:47 PM marc jacobs stores worldwide helena bonham carter www.marcjacobs.com photographed by juergen teller marc jacobs stores worldwide helena bonham carter www.marcjacobs.com photographed by juergen teller NEW YORK LOS ANGELES BOSTON LAS VEGAS MIAMI DALLAS SAO PAULO LONDON PARIS SAINT TROPEZ BRUSSELS ANTWERPEN KNOKKE MADRID ATHENS ISTANBUL MOSCOW DUBAI HONG KONG BEIJING SHANGHAI MACAU JAKARTA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE SEOUL TOKYO SYDNEY DVF.COM NEW YORK LOS ANGELES BOSTON LAS VEGAS MIAMI DALLAS SAO PAULO LONDON PARIS SAINT TROPEZ BRUSSELS ANTWERPEN KNOKKE MADRID ATHENS ISTANBUL MOSCOW DUBAI HONG KONG BEIJING SHANGHAI MACAU JAKARTA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE SEOUL TOKYO SYDNEY DVF.COM IN CELEBRATION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF SWAROVSKI’S SUPPORT OF THE CFDA FASHION AWARDS AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES NEW YORK # LOS ANGELES COSTA MESA # CHICAGO # MIAMI # 1 800 426 3088 # WWW.ATELIERSWAROVSKI.COM BRAIDED BRACELET PHOTOGRAPHED BY MITCHELL FEINBERG IN CELEBRATION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF SWAROVSKI’S SUPPORT OF THE CFDA FASHION AWARDS AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES NEW YORK # LOS ANGELES COSTA MESA # CHICAGO # MIAMI # 1 800 426 3088 # WWW.ATELIERSWAROVSKI.COM BRAIDED BRACELET PHOTOGRAPHED BY MITCHELL FEINBERG WWD Published by Fairchild Fashion Group, a division of Advance Magazine Publishers Inc., 750 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 EDITOR IN CHIEF ADVERTISING Edward Nardoza ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER, Melissa Mattiace ADVERTISING DIRECTOR, Pamela Firestone EXECUTIVE EDITOR, BEAUTY Pete Born PUBLISHER, BEAUTY INC, Alison Adler Matz EXECUTIVE EDITOR Bridget Foley SALES DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR, Jennifer Marder EDITOR James Fallon ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER, INNERWEAR/LEGWEAR/TEXTILE, Joel Fertel MANAGING EDITOR Peter Sadera EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL FASHION, Matt Rice MANAGING EDITOR, FASHION/SPECIAL REPORTS Dianne M. -

The Male Fashion Bias Mr. Mark Neighbour a Practice

The Male Fashion Bias Mr. Mark Neighbour A Practice-Led Masters by Research Degree Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology Discipline: Fashion Year of Submission: 2008 Key Words Male fashion Clothing design Gender Tailoring Clothing construction Dress reform Innovation Design process Contemporary menswear Fashion exhibition - 2 - Abstract Since the establishment of the first European fashion houses in the nineteenth century the male wardrobe has been continually appropriated by the fashion industry to the extent that every masculine garment has made its appearance in the female wardrobe. For the womenswear designer, menswear’s generic shapes are easily refitted and restyled to suit the prevailing fashionable silhouette. This, combined with a wealth of design detail and historical references, provides the cyclical female fashion system with an endless supply of “regular novelty” (Barthes, 2006, p.68). Yet, despite the wealth of inspiration and technique across both male and female clothing, the bias has largely been against menswear, with limited reciprocal benefit. Through an exploration of these concepts I propose to answer the question; how can I use womenswear patternmaking and construction technique to implement change in menswear design? - 3 - Statement of Original Authorship The work contained in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma at any other higher educational institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made. Signed: Mark L Neighbour Dated: - 4 - Acknowledgements I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone who supported and assisted this project. -

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Weronika Gaudyn December 2018 STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART Weronika Gaudyn Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor School Director Mr. James Slowiak Mr. Neil Sapienza _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Ms. Lisa Lazar Linda Subich, Ph.D. _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Sandra Stansbery-Buckland, Ph.D. Chand Midha, Ph.D. _________________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT Due to a change in purpose and structure of haute couture shows in the 1970s, the vision of couture shows as performance art was born. Through investigation of the elements of performance art, as well as its functions and characteristics, this study intends to determine how modern haute couture fashion shows relate to performance art and can operate under the definition of performance art. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee––James Slowiak, Sandra Stansbery Buckland and Lisa Lazar for their time during the completion of this thesis. It is something that could not have been accomplished without your help. A special thank you to my loving family and friends for their constant support -

Handcrafted in Australia. Since 1969

2019-2020 Handcrafted in Australia. Since 1969. From golden coastlines and endless JACARU HATS sun-baked horizons, dense tropical rainforests and rugged bushland, 4 Kangaroo red deserts and vast sweeping New Premium Range plains, Australia is a country of 8 Western unparalleled uniqueness Our two most iconic hats are now also available in a new premium version - a country like no other. 10 Exotic in addition to our standard models. Available in brown and black. Since its beginning in 1969, the Jacaru brand has reflected this 14 Breeze Australian landscape, its unique lifestyle and the spirit that is 16 Traditional Australia - wild, untameable, strong and courageous. 18 Australian Wool 50 years on, Jacaru has established Ladies itself as one of Australia’s finest 20 accessories brands, selling in over contents 50 countries worldwide. Today, 24 Kid’s we are prouder than ever to be Australian. 26 Summer Lovin’ We believe in Australian made 34 Safety and Workwear products, handcrafted from the finest Australian materials. 37 Wallets & Purses We are proud that our products are 38 Leather Belts designed and made with dedication in the hands of our craftspeople located in Burleigh on the iconic 40 Fur Accessories Gold Coast of Queensland, Australia. 41 Keyrings We are proud of our heritage and 42 Oilskin Waxed Products will continue to work passionately to bring you quality products that 44 Hat Accessories are quintessentially Australian. 45 Scarves Established in 1969, the Jacaru brand reflects the spirit that is 46 Product Care Australia - wild, untameable, strong and courageous. 47 Size Chart Jacaru - Handcrafted in Australia. -

Chinese New Year Celebration and Shopping Stroll

HIGHLAND PARK VILLAGE CHINESE NEW YEAR CELEBRATION AND SHOPPING STROLL Saturday, February 8, 2020 4-8 PM HIGHLAND PARK VILLAGE 诚邀您 中国年 庆贺与购物之夜 2020年2月8日,周日 晚上4点-8点 NEWS RELEASE HIGHLAND PARK VILLAGE CELEBRATES CHINESE NEW YEAR WITH FESTIVE ENTERTAINMENT AND LUXURY SHOPPING PROMOTIONS ON FEBRUARY 8, 2020 DALLAS, TX (December 2019) - Highland Park Village, Dallas’ landmark luxury shopping and dining destination, is thrilled to host an experiential Chinese New Year Celebration on Saturday, February 8, 2020. From exclusive shopping offers and festive promotions from fashion’s most renowned brands, to live cultural performances and themed holiday entertainment, guests from near and far are invited to enjoy the culture and customs of Chinese New Year. In addition, stroll and peruse a unique outdoor market around Livingston Court with Chinese inspired food and goods. What: Highland Park Village’s Chinese New Year Celebration and Shopping Stroll With a variety of holiday entertainment and activations taking place on the final day of Chinese New Year, an occasion traditionally marked by magnificent Lantern Festivals, Highland Park Village is bringing to life the captivating magic of new beginnings and the Year of the Rat. In partnership with the US-China Chamber of Commerce, Dallas and Visit Dallas, festivities include: • Live cultural performances from 4 PM – 8 PM, including a Lion Dance • Exclusive shopping promotions and discounts, lucky gift raffles, complimentary customization services, festive refreshments and more at numerous stores until 8:00 PM • Experiential outdoor market with traditional food and exclusive Chinese vendors • Traditional Chinese lanterns displayed over Livingston Court, between Celine and Balenciaga When: Saturday, February 8, 2020 Where: 47 Highland Park Village, Dallas, Texas 75205 About Highland Park Village: Highland Park Village is a favorite lifestyle destination among locals and guests from around the world, as it has been for many generations. -

The Mini Skirt Danielle Hueston New York City College of Technology Textiles

The Mini Skirt Danielle Hueston New York City College of Technology Textiles When I was six my mother and I took one of our weekly day shopping trips to the mall. On our way back we stopped at this local thrift store. This being one of the first times I had ever experienced one, everything seemed so different and weird, in a good way. I wasn’t used to there only being one of everything, or one store that sold clothes, books, toys, home decor and shoes.Walking down the ‘bottoms aisle’ is where I first came across it. It was black and flowy, probably a cotton material, with a black elastic band around the waist. I wanted it, I needed it. It was the perfect mini skirt. It reminded me of the one I saw Regina George wear in the Hallway Scene in the movie ‘Mean Girls’ a few months prior and had to get it, even though it was a “little” big. There was only one, I was going to make it work. When Monday came I wasted no time showing off my new skirt at school. It made me feel like a whole new person. At some point of the day however my teacher had stepped out of the room to talk to another teacher, in conjunction one of my classmates playfully grabbed my pencil out of my hand, to which I decided to chase him around the room to retrieve it back. I tripped and my skirt fell right to my ankles, in front of the entire class. -

Jeanne Lanvin

JEANNE LANVIN A 01long history of success: the If one glances behind the imposing façade of Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, 22, in Paris, Lanvin fashion house is the oldest one will see a world full of history. For this is the Lanvin headquarters, the oldest couture in the world. The first creations house in the world. Founded by Jeanne Lanvin, who at the outset of her career could not by the later haute couture salon even afford to buy fabric for her creations. were simple clothes for children. Lanvin’s first contact with fashion came early in life—admittedly less out of creative passion than economic hardship. In order to help support her six younger siblings, Lanvin, then only fifteen, took a job with a tailor in the suburbs of Paris. In 1890, at twenty-seven, Lanvin took the daring leap into independence, though on a modest scale. Not far from the splendid head office of today, she rented two rooms in which, for lack of fabric, she at first made only hats. Since the severe children’s fashions of the turn of the century did not appeal to her, she tailored the clothing for her young daughter Marguerite herself: tunic dresses designed for easy movement (without tight corsets or starched collars) in colorful patterned cotton fabrics, generally adorned with elaborate smocking. The gentle Marguerite, later known as Marie-Blanche, was to become the Salon Lanvin’s first model. When walking JEANNE LANVIN on the street, other mothers asked Lanvin and her daughter from where the colorful loose dresses came. -

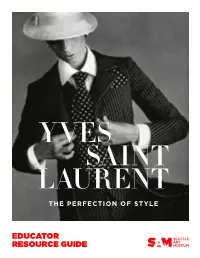

Yves Saint Laurent: the Perfection of Style: Educator Resource Guide

EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE OVERVIEW ABOUT THE EXHIBITION Organized by the Seattle Art Museum in partnership with the Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent, Yves Saint Laurent: The Perfection of Style highlights the legendary fashion designer’s 44-year career. Known for his haute couture designs, Yves Saint Laurent’s creative process included directing a team of designers working to create his vision of each garment. He would often begin by sketching the clothing he imagined, then a team would work to sew and create his designs. After the first version of the garment was created with simple fabric called muslin, Saint Laurent would select the final fabric for the garment. Under Saint Laurent’s direction, his team would piece the garment together—first on amannequin , next on a model. Working collaboratively, the team made changes according to Saint Laurent’s decisions, sewing new parts before the final garment was finished. Taking inspiration from changes in society around him, Saint Laurent adapted his designs over the years. Starting his career designing custom-made clothing worn by upper-class women, he shifted his focus to create clothing that more people would want to wear and could afford. He responded to contemporary changes of the time and pushed gender, class, and expressive boundaries of fashion. He created innovative, glamorous pantsuits for women, ready-to-wear clothing for the wider population, and high fashion inspired by what he saw young people wearing on the street. In 1971 Yves Saint Laurent summed this up with one sentence, “What I want to do is shock people, force them to think.” The exhibition features over 100 haute couture and ready-to-wear garments.