AIAL Forum 74

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Assembly Distr.: General 16 October 2008

United Nations A/63/489 General Assembly Distr.: General 16 October 2008 Original: English Sixty-third session Agenda item 105 (k) and (l) Appointments to fill vacancies in subsidiary organs and other appointments: appointment of the judges of the United Nations Dispute Tribunal; appointment of the judges of the United Nations Appeals Tribunal Report of the Internal Justice Council I. Introduction 1. By its resolutions 61/261 and 62/228, the General Assembly approved the framework for a new system for the internal administration of justice within the United Nations to be introduced as of 1 January 2009. As part of that framework it established the Internal Justice Council to help ensure independence, professionalism and accountability in the new system. In paragraph 37 (b) of its resolution 62/228 the Assembly requires the Council, as one of its primary tasks, to “provide its views and recommendations to the General Assembly on two or three candidates for each vacancy in the United Nations Dispute Tribunal and the United Nations Appeals Tribunal, with due regard to geographical distribution”. 2. The Internal Justice Council derives from a recommendation by the expert Redesign Panel, established by the General Assembly in its resolution 59/283,1 which proposed an entirely new system for the internal administration of justice, in which professional judges would issue binding tribunal decisions in a first-instance United Nations Dispute Tribunal (unlike previous peer review bodies that only had the power to make non-binding recommendations). An appeal would lie to a newly established United Nations Appeals Tribunal, comprising seven highly experienced judges. -

Passages in the Law

Passages in the Law Brian Tamberlin, QC Deputy President Administrative Appeals Tribunal Talk at the office of Carroll and O’Dea 12 February 2013 1 Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen. One bonus of being asked to speak today was the opportunity to get better acquainted with the history of the firm through the prism of your centenary publication “The Vision Splendid”. It sets out the history and culture of the firm over most of the last one hundred and fifteen years of it’s existence. Many of the anecdotes resonate with my fond recollections of the personalities referred to such as Clive Evatt, Frank McAlary, Barry Mahoney, Ray Loveday and Paul Flannery. Over the past fifty years inevitably I have come across many members of the firm. My most continuous acquaintance has been with Michael O’Dea whom I first met in 1965 and who in 1968 succeeded me as an alderman of North Sydney Council of which he later became Lord Mayor. I admire the culture and vision of the firm and its engagement with the community especially through its extensive pro-bono program. Not the least of its achievements is keeping its name and identity, as well is its strongly personal culture in the present environment of law firm mergers, which, by change of name and often of culture, tend to become anonymous commercial entities abandoning a valuable part of their identity and esteem. The name Carroll and O’Dea has a personal ring rather than those global operations with names such as Linklaters, Ashurst or Quality Solicitors. -

Australian Law Journal

THE AUSTRALIAN LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 81 January 2007 — December 2007 GENERAL EDITOR MR JUSTICE P W YOUNG AO ASSISTANT GENERAL EDITORS ANGELINA GOMEZ JENNIFER SINGLE PRODUCTION EDITOR CHERYLE KING INDEX ALAN WALKER BA (Hons), DipLib LAWBOOK CO. Published in Sydney by Lawbook Co. 100 Harris Street, Pyrmont, NSW Customer Service and Sales Inquiries Tel: 1300 304 195 Fax: 1300 304 196 Web: www.thomson.com.au Email: [email protected] Editorial Inquiries Tel: 61 2 8587 7000 HEAD OFFICE 100 Harris Street PYRMONT NSW 2009 Tel: 61 2 8587 7000 Fax: 61 2 8587 7100 ISSN 0004-9611 Typeset by Lawbook Co., Pyrmont, NSW Printed by Ligare Pty Ltd, Riverwood, NSW The Australian Law Journal — Vol 81 iii The mode of citation of this volume of the AUSTRALIAN LAW JOURNAL will be as follows: (2007) 81 ALJ TABLE OF CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN LAW JOURNAL TABLE OF AUTHORS ........................................................................ v TABLE OF CASES............................................................................... ix AUSTRALIAN LAW JOURNAL, VOL 81, No 1, January 2007 to No 12, December 2007 .................. 1-968 INDEX................................................................................................... 969 AUSTRALIAN LAW JOURNAL REPORTS BOOK 1 TABLE OF CASES REPORTED ......................................................... v CORRIGENDA ..................................................................................... ix AUSTRALIAN LAW JOURNAL REPORTS, VOL 81 ....................... 1-904 BOOK 2 TABLE OF CASES REPORTED ........................................................ -

The Faculty of Law at the University of Sydney Is at the Forefront of Legal Education Both in Australia and Overseas

Single Unit Enrolment @ Sydney Law School Semester 2 The Faculty of Law at The University of Sydney is at the forefront of legal education both in Australia and overseas. Through high quality teaching and research, the Faculty has achieved a national and international reputation for critical and independent scholarship. Participants in our Legal Professional Development (LPD) program are able to “audit” Postgraduate Units of Study, attending lectures and receiving copies of Lecture Notes. LPD students do not undertake examinations. Study by this method is for interest and information purposes only. Courses are offered by one of two methods, either attendance one night per week for 13 weeks commencing the week beginning Monday 27th of July 2009 or by “intensive” mode. Courses offered as intensive units are normally conducted over four or five days. Location: The majority of courses are held at the New Faculty of Law Building, Eastern Avenue, Camperdown Campus, University of Sydney. A small number of courses are conducted at the Old Faculty of Law Building, St James Campus, 173-175 Phillip Street, Sydney, or other central Sydney locations. It is also possible to undertake courses which are conducted as part of the Sydney Law School in Europe program (Cambridge and Berlin). For detailed advice please see: http://www.law.usyd.edu.au/fstudent/coursework/LLM/index.shtml The Sydney Law School also offers a subject at Jiaotong Univeristy, Shanghai, China. Cost: Sydney Law School: $2,550 (GST free). Sydney Law School in Europe: $3,360 (GST free). LAWS6001-52 “Chinese Laws & Legal Systems”: Please see Shanghai Winter School webpage for costs: http://www.law.usyd.edu.au/cstudent/shanghai/ This registration fee includes all tuition and university materials. -

AAT Annual Report 2009-10 Appendix 1 Members of the Tribunal [PDF

ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 2009–10 APPENDIX 1: MEMBERS OF THE TRIBUNAL Tribunal members, 30 June 2010 President The Honourable Justice GK Downes AM New South Wales Presidential members Federal Court The Honourable Justice ACB Bennett AO The Honourable Justice RF Edmonds The Honourable Justice RJ Buchanan Deputy Presidents Mr J Block The Honourable BJM Tamberlin QC Mr RP Handley Non-presidential members Senior Members Mr MD Allen (G,V,T,S) Ms G Ettinger (G,V,T,S) Ms NP Bell (G,V,S) Ms N Isenberg (G,V,S) Mr PW Taylor SC (G,V,T) Ms JF Toohey (G,V) Ms AK Britton (G,V) Mr SE Frost (G,V,T) Mr D Letcher QC (G,V,T) Ms JL Redfern (G,V,T) Members Dr IS Alexander (G,V) Air Vice Marshal Dr TK Austin (G,V) Dr JD Campbell (G,V) Mr DM Connolly AM (G,V,S) Dr H Haikal-Mukhtar (G,V) Dr TJ Hawcroft (G,V) Mr TC Jenkins (G,V,T) Professor GAR Johnston AM (G,V) Mr IW Laughlin (G,T) Dr TM Schafer (G,V) Professor TM Sourdin (G,V) Dr MEC Thorpe (G,V) Dr SH Toh (G,V) Notes Presidential members and Senior Members are listed by date of appointment, Members are listed alphabetically. Presidential members may exercise the powers of the Tribunal in all of the Tribunal’s divisions. Senior Members and Members may exercise the powers of the Tribunal only in the divisions to which they have been assigned. The divisions to which Senior Members and Members have been assigned are indicated as follows: G General Administrative Division V Veterans’ Appeals Division T Taxation Appeals Division S Security Appeals Division 96 APPENDIX 1: MEMBERS OF THE TRIBUNAL -

Sydney Law School 2011 Contents

your guide to POSTGRADUATE STUDY At sydney lAw School 2011 cOntenTS 02 Message from the dean 04 the Sydney Advantage 05 New for 2011: Banking & Finance Law 06 New for 2011: Climate Law 08 offshore opportunities 10 Centres & institutes 12 Staff 15 international Visitors 20 Scholarships & Prizes 22 State-of-the-Art Facilities 23 research Programs 26 Master of Laws (LLM) by Coursework 31 Specialist Coursework Programs 55 Course rules 59 2011 units of Study 119 2011 Postgradute Lecture timetable 135 Application information – domestic Students 137 Fees 2011 – domestic Students 138 Application information – international Students 140 Fees 2011 – international Students 2 ABout SydNey LAW schooL WelcOmE from ThE Dean i would like to extend a warm welcome Professor Joanna Bird – Professor Jonathan Verschuuren, to each of you as you embark on – introduction to Australian Business tax university of tilburg, the Netherlands postgraduate studies in law. the Sydney with Professor graeme Cooper – Professor Laura e. Little, temple Law School provides one of the largest – islamic trade & Finance Law with university, Philadelphia, uSA range and number of subjects at the dr Salim Farrar – Professor James Cox, duke university, postgraduate level in Law in Australia, – international & Australian Climate Law North Carolina, uSA reflecting a high demand for specialist with Professor rosemary Lyster – Professor Bernhard Schlink, humboldt skills in a globalised legal environment. – disability and human rights in university, Berlin, germany this guide sets out the details of the international & domestic Law with We will continue to offer subjects subjects we are offering in 2011, along Professor ron McCallum & that are in high demand such as with the many options that are available dr Belinda Smith international Business Law with for specialisation. -

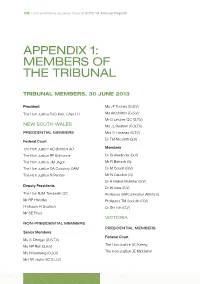

Appendix 1: Members of the Tribunal

Appendixes APPENDIX 1: MEMBERS OF THE TRIBUNAL TRIBUNAL MEMBERS, Members 30 JUNE 2014 Dr IS Alexander (G,V) President Mr R Bartsch (G) The Hon Justice DJC Kerr, Chev LH Dr M Couch (G,V) Mr N Gaudion (G) NEW SOUTH WALES Dr H Haikal-Mukhtar (G,V) PRESIDENTIAL MEMBERS Dr W Isles (G,N,V) Professor GAR Johnston AM (G,V) Federal Court Professor RC McCallum AO (G,N) The Hon Justice AC Bennett AO Professor TM Sourdin (G,V) The Hon Justice RF Edmonds Dr SH Toh (G,N,V) The Hon Justice JM Jagot The Hon Justice N Perram VICTORIA Deputy Presidents The Hon BJM Tamberlin QC PRESIDENTIAL MEMBERS Mr RP Handley Federal Court Appendix 1: Members of the Tribunal Professor R Deutsch The Hon Justice SC Kenny Mr SE Frost The Hon Justice JE Middleton NON-PRESIDENTIAL MEMBERS Deputy Presidents Miss SA Forgie Senior Members Mr JW Constance Ms G Ettinger (G,S,T,V) Ms FJ Alpins Ms NP Bell (G,N,S,V) 2013–14 Annual2013–14 Report Ms N Isenberg (G,S,V) NON-PRESIDENTIAL MEMBERS Mr PW Taylor SC (G,T,V) Senior Members Ms JF Toohey (G,N,S,V) Mr JR Handley (G,N,T,V) Ms AK Britton (G,N,S,V) Mr GD Friedman (G,S,V) Mr D Letcher QC (G,N,T,V) Mr FD O’Loughlin (G,T,V) Ms JL Redfern (G,N,S,T,V) Mr E Fice (G,S,T,V) Mrs G Lazanas (G,T,V) Members Dr TM Nicoletti (G,V) Dr R Blakley (G,V) Administrative Appeals Tribunal Tribunal Appeals Administrative Ms L Coulson Barr (G,N) 116 Brigadier C Ermert (ret’d) (G,T,V) Deputy President Dr GL Hughes (G,T,V) Ms KJ Bean Dr RJ McRae (G,N,V) NON-PRESIDENTIAL MEMBERS Ms RL Perton OAM (G,N,S,V) Senior Members Miss EA Shanahan (G,V) Mr RW Dunne (G,T,V) -

AAT Annual Report 2010-11 Appendix 1 Members of the Tribunal [PDF

ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 2010–11 APPENDIX 1: MEMBERS OF THE TRIBUNAL Tribunal members, 30 June 2011 President The Honourable Justice GK Downes AM New South Wales Presidential members Federal Court The Honourable Justice ACB Bennett AO The Honourable Justice RF Edmonds The Honourable Justice RJ Buchanan The Honourable Justice JM Jagot Deputy Presidents Mr J Block The Honourable BJM Tamberlin QC Mr RP Handley Non ‑presidential members Senior Members Mr MD Allen (G,S,T,V) Ms G Ettinger (G,S,T,V) Ms NP Bell (G,S,V) Ms N Isenberg (G,S,V) Mr PW Taylor SC (G,T,V) Ms JF Toohey (G,V) Ms AK Britton (G,V) Mr SE Frost (G,T,V) Mr D Letcher QC (G,T,V) Ms JL Redfern (G,T,V) Members Dr IS Alexander (G,V) Air Vice-Marshal Dr TK Austin (G,V) Dr H Haikal-Mukhtar (G,V) Dr TJ Hawcroft (G,V) Mr TC Jenkins (G,T,V) Professor GAR Johnston AM (G,V) Mr IW Laughlin (G,T) Dr TM Schafer (G,V) Professor TM Sourdin (G,V) Dr MEC Thorpe (G,V) Dr SH Toh (G,V) Notes Presidential members and Senior Members are listed by date of appointment, Members are listed alphabetically. Presidential members may exercise the powers of the Tribunal in all of the Tribunal’s divisions. Senior Members and Members may exercise the powers of the Tribunal only in the divisions to which they have been assigned. The divisions to which Senior Members and Members have been assigned are indicated as follows: G General Administrative Division S Security Appeals Division T Taxation Appeals Division V Veterans’ Appeals Division 96 APPENDIX 1: MEMBERS OF THE TRIBUNAL Victoria Presidential -

Udicial Ournal

The JULY - SEPTEMBERPHILPHILPHIL 2003 VOL. 5, ISSUE NO. 17 AAA JJJUDICIALUDICIAL JJOURNALOURNAL Asia Pacific Judicial Educators Forum i The PHILPHILPHIL AAA JULY-SEPTEMBER 2003 VOL. 5, ISSUE NO. 17JJUDICIAL OURNAL ASIA PACIFIC JUDICIAL EDUCATORS FORUM (APJEF) I. MESSAGES II. REPORTS ON THE STATE OF JUDICIAL EDUCATION IN AUSTRALASIA III. LECTURES IV. CHARTER iv The PHILJA Judicial Journal. The PHILJA Judicial Journal is published four times a year, every quarter, January through December, by the Research and Linkages Office of the Philippine Judicial Academy (PHILJA). The Journal contains articles and contributions of interest to members of the Judiciary, particularly judges, as well as law students and practitioners. The views expressed by the contributors do not necessarily reflect the views of either the Academy or its editorial board. Editorial and general offices are located at PHILJA, 3rd Floor, Centennial Building, Supreme Court, Padre Faura St., Manila. Telefax No.: 552-9524 Email: [email protected] CONTRIBUTIONS. The PHILJA Judicial Journal invites the submission of unsolicited articles. Please include author’s name and biographical information. The editorial board reserves the right to edit articles submitted for publication. Copyright © 2003 by The PHILJA Judicial Journal. All rights reserved. For more information, please visit the PHILJA website at http://philja.supremecourt.gov.ph. v SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. HILARIO G. DAVIDE, Jr. ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. JOSUE N. BELLOSILLO Hon. REYNATO S. PUNO Hon. JOSE C. VITUG Hon. ARTEMIO V. PANGANIBAN Hon. LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING Hon. CONSUELO YÑARES-SANTIAGO Hon. ANGELINA SANDOVAL-GUTIERREZ Hon. ANTONIO T. CARPIO Hon. MA. ALICIA AUSTRIA-MARTINEZ Hon. -

Administrative Appeals Tribunal Annual Report 2012-13 Appendix 1

128 / Administrative Appeals Tribunal 2012–13 Annual Report APPENDIX 1: MEMBERS OF THE TRIBUNAL TRIBUNAL MEMBERS, 30 JUNE 2013 President Ms JF Toohey (G,S,V) The Hon Justice DJC Kerr, Chev LH Ms AK Britton (G,S,V) Mr D Letcher QC (G,T,V) NEW SOUTH WALES Ms JL Redfern (G,S,T,V) PRESIDENTIAL MEMBERS Mrs G Lazanas (G,T,V) Dr TM Nicoletti (G,V) Federal Court The Hon Justice AC Bennett AO Members The Hon Justice RF Edmonds Dr IS Alexander (G,V) The Hon Justice JM Jagot Mr R Bartsch (G) The Hon Justice DA Cowdroy OAM Dr M Couch (G,V) The Hon Justice N Perram Mr N Gaudion (G) Dr H Haikal-Mukhtar (G,V) Deputy Presidents Dr W Isles (G,V) The Hon BJM Tamberlin QC Professor GAR Johnston AM (G,V) Mr RP Handley Professor TM Sourdin (G,V) Professor R Deutsch Dr SH Toh (G,V) Mr SE Frost VICTORIA NON-PRESIDENTIAL MEMBERS PRESIDENTIAL MEMBERS Senior Members Federal Court Ms G Ettinger (G,S,T,V) Ms NP Bell (G,S,V) The Hon Justice SC Kenny Ms N Isenberg (G,S,V) The Hon Justice JE Middleton Mr PW Taylor SC (G,T,V) Appendix 1: Members of the Tribunal / 129 Deputy Presidents NON-PRESIDENTIAL MEMBERS Miss SA Forgie Senior Members Mr JW Constance Mr BJ McCabe (G,S,T,V) Ms FJ Alpins Associate Professor PM McDermott RFD (G,T,V) NON-PRESIDENTIAL MEMBERS Dr KStC Levy RFD (G,T,V) Senior Members Mr RG Kenny (G,T,V) Mr JR Handley (G,T,V) Members Mr GD Friedman (G,S,V) Dr ML Denovan (G,V) Mr FD O’Loughlin (G,T,V) Dr GJ Maynard, Brigadier (retd) (G,V) Mr E Fice (G,S,T,V) Dr M Sullivan (G,V) Members Dr PL Wulf (G,T) Dr R Blakley (G,V) SOUTH AUSTRALIA Dr KJ Breen AM (G,V) -

Supreme Court Annual Review 2016-17

SUPREME COURT OF THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY ANNUAL REVIEW 2016 –17 SUPREME COURT OF THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY ANNUAL REVIEW 2016 –17 “ The English jurist Lord Chancellor Frederick Maugham described lawyers some seven decades ago as ‘custodians of civilisations, than which there can be no higher or nobler duty’, and his words are as apt today as they were then. This is not empty grandiloquence from a quieter or more genteel past, because you do, now, become part of the mechanism which guards the lynchpin of our civil society, the rule of law, and you must take that responsibility seriously. Without it people can lose their human rights or at least have them ignored… The rule of law is no empty mantra. It should be a bright lodestar to underpin your professional work. …It is an underpinning of the kind of civilised society in which we all hope to live.” The Hon Justice Richard Refshauge addressing newly admitted lawyers at the Admission Ceremony 20 August 2010 CONTENTS CONTENTS WELCOME 5 Chief Justice Helen Murrell 5 Principal Registrar Philip Kellow 6 ABOUT THE COURT 9 Strategic Statement 10 H i s t o r y 11 Jurisdiction 12 Judges of the Court 13 Resident Judges 13 Additional Judges 19 Acting Judges 19 Russell Fox Library 20 Sheriff’s Office 24 HIGHLIGHTS 27 Indigenous awareness 28 Involvement with the legal community 30 Ceremonial sittings 33 Selected cases 41 TECHNOLOGY AND ONGOING PROJECTS 51 New Supreme Court building 52 Court technology 56 CASE MANAGEMENT 59 Criminal listings 60 Civil case management 60 Central civil list 61 Statistics 62 ANNUAL REVIEW 2016 –17 3 WELCOME Chief Justice Helen Murrell and Supreme Court Registrar Annie Glover: Construction site of new Supreme Court building 4 SUPREME COURT OF THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY WELCOME Welcome Chief Justice Helen Murrell The 2016/2017 year saw many changes to the Court, including the Court Bench. -

1 the HON. MURRAY GLEESON AC QC Edited Transcript of a Three-Part

1 THE HON. MURRAY GLEESON AC QC Edited transcript of a three-part interview with Juliette Brodsky for the NSW Bar Association August - September 2018 Part 1 14 August 2018 Q Juliette Brodsky interviewing Mr Murray Gleeson for the NSW Bar Association oral history – thank you very much for making time to speak with me today. A You’re welcome. Q It’s the eve of your 80th birthday at the time of this recording, and it’s been ten years since you concluded your time as Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia. Can I just ask a quick question for my own curiosity – what activities are you currently involved in? A If you mean professional activities – Q Yes. A I’m a non-permanent Judge of the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal which means that for most years I spend one month sitting on that court. In addition, I am often invited to make speeches to judges and barristers and people of that kind, and I do some commercial arbitrations, international and domestic. Q You’re patron of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators Australia. A Yes, I have been for many years. It’s quite likely that I became patron of that body before it took on its current corporate form. The organisation would know that better than I do. But I think I have had a connection with that body, or its predecessor, since I was Chief Justice of NSW. Q Your views about (arbitration) as a form of alternative dispute resolution? There are some who believe ADR should just be called “dispute resolution”.