Armageddon: Raging Battle for Bible History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GREETINGS to EDITOR EMERITUS DR SHIMON BAKON on HIS 100Th BIRTHDAY

NEWS OF THE JEWISH BIBLE ASSOCIATION GREETINGS TO EDITOR EMERITUS DR SHIMON BAKON ON HIS 100th BIRTHDAY Dr. Shimon Bakon began his association with The Jewish Bible Quarterly in 1975 with Volume 4:2, when he joined the Editorial Board of the journal then known as Dor leDor. He was appointed Assistant Editor in 1976, starting with Volume 4:3, and Associate Editor in 1978, starting with Volume 7:1. He was appointed Editor in 1987, starting with Volume 16:2, and was Editor for 25 years until 2012. Born in Czechoslovakia, he attended the Jewish high school in Brno, received private tutoring in Talmud from his father, and in 1939 earned a Ph.D. in philosophy at Masaryk University. After reaching the United States, he studied for three years at Yeshiva Torah Vodaath in Brooklyn. In January 1942, he joined the U.S. Army, served with distinction in North Africa and Italy, and received an Honorable Discharge in 1945. Thereafter, he took a post-doctoral fellowship in philosophy at Columbia University in New York, and went on to be director of Jewish education first in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and then in Springfield, Massachusetts. In Springfield, he was instrumental in establishing a branch of Boston Hebrew College, and for more than 10 years served as its administrator and lecturer in Jewish Philosophy. In 1974, he made aliya to Israel with his wife and children, and soon after began his association with this journal. The directors of the Jewish Bible Association and the Editorial Board of The Jewish Bible Quarterly extend their greetings and blessings Dr. -

MAY 5, 1961 Israel

11a,1a·. a.a.gi '10· ,_:~ -:a.-. ..,:Nr :1:.~ _.. :.. ·- ,(,~_. •:t, ............. x. ...'.L --·- NEWS Arab Block Fails To P.-t Through ,11.. Resolution ·At UN ., PINF.8 OP 15 POUNDS EACH THE ONLY ANGLO-JEWISH WEEKLY IN R. I. AND SOUiHEAST MASS. UNITED NATIONS, N. Y. - were lmpased in London on 8 The Arab bloc's only drive to put members of· the neo-fasclst Bri- VOL nu N ,...'""'AY MAY 1961 16 PAGES tlsh National Party for disturb- __· __ ,_"• __ 0_· __________9 ,.._~ ___ • ___ 5' ________________ _ through an anti-Israel resolution at this year's General Assembly Ing and carrying anti-Jewish PoSt failed last week. Two clauses of a ers at a rpemorial meeting in Rabbi Sandrow Urges Support Of -resolution aimed at establishment honor of the Warsaw Ghetto of United Nations cuatodlan over heroes. The court warned them Kennedy's School Aid Program property allegedly left 1n Israel by they would receive heavy fines the Arab refugees were defeated and prison terms If they were KIAMESHA LAKE, N. Y. - stltutions, but declared that such In the Assembly's closing day, fall brought up on similar charges In Support for President Kennedy's schools "muat be supported by the Ing to get the needed two-thirds the future. program for federal aid to public families who want their children majority. JEWISH STUDENTS WISHING. schools, and the ellmlnation· from trained 1n them or by Jewish com One of the clauses was voted to take college entrance exams at such a program of government aid munity councils or Welfare Funds down by 44 votes in favor, 38 Mc0111 University will be offered to religious schools, was urged or Pederations whoae respon against with 12 abstentions; the the opportunity to take tests on here last week by Rabbi F.dward siblllty It ts to enhance the teach second clause was defeated by a a day other than Saturday, when T. -

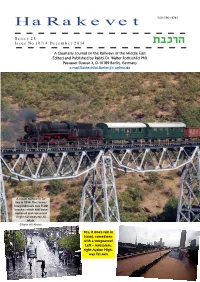

Issue No.107/4 December 2014 ,Cfrv

HaRakevet ISSN 0964-8763 Series 28 Issue No.107/4 December 2014 ,cfrv A Quarterly Journal on the Railways of the Middle East Edited and Published by Rabbi Dr. Walter Rothschild PhD Passauer Strasse 4, D-10789 Berlin, Germany e.mail:[email protected] A steam railtour in Tur- key in 2014. The former Kriegslok hauls two TCDD coaches which had been restored and repainted single-handedly by Ali Aksin. (Photo Ali Aksin). Yes, it does rain in Israel, sometimes with a vengeance! Left - Jerusalem, right Ayalon High- way Tel Aviv 107:0 concluded Tuesday morning with the ar- rests of over 5 managers and supervi- sors. According to police, the investiga- EDITORIAL tion – conducted with the full cooperation A bizarre change of emphasis in this issue. After moaning recently about the of Israel Railways CEO, Boaz Zafrir – de- lack of any positive news from most countries in the Middle East, the Editor found lots termined that the sanitation employees of information at Innotrans in Berlin and yet more in relation to proposed conferences colluded for months to commit bribery, (to which he could NOT go) in Dubai and Riyadh, discussing all sorts of fancy, expen- money laundering, fraud, and tax offenses sive and hi-tech projects throughout the region! Of course there is a major disconnect totaling “tens of millions” of shekels. between what one reads in the newspapers and what one sees as a serious discussion In a statement, police said the investi- about building tramways in Kurdistan. So a lot of this is presented here, in this issue, at gation was launched after suspicions were the expense of several historical items which have had to be held over to the next edi- raised that a number of sanitary inspectors tion. -

Temple Beth Shalom, We Hoped That We Could Be Part of a Larger Group of People All Doing the Same Thing

4 Upcoming Events 8 The Buzz 9 Chai-er Learning 10 The Game Plan 12 Simcha Station 13 Yahrzeits 16 Presidential Address 17 Mitzvah Corps 18 Donations Announcements! While the temple building is closed, you can still reach all of our staff members. Call the temple line and it will ring through to our cell phones. 4 August Events - All Online! Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Programs are 1 subject to 10am— change! Adaline Please check Mendel FA the eWindow and our social 8:30pm— media for the Havdalah w/ most up to the Bar-Lev date info! Family 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 10:30am— 10:30am— 10:30am— 10:30am— 9:30am— 8:30pm— Boker Tov Acting Parshat Shabbat Songs Havdalah w/ Gardening Masterclass 12pm— Masterclass HaShavua w/ Marc the Bar-Lev Live From The 4:30pm— 6:30pm— Family Holy Land - Healing Service Erev Shabbat Jerusalem 7:30pm— Services Mixology Masterclass 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 10:30am— 10:30am— 10:30am— 9:30am— 10am— Boker Tov Acting Parshat HaShavua Shabbat Songs Emma & Noah 12pm— Masterclass 4:30pm— w/ Marc Matros FA 7:30pm— Live From The Quarantining 6:30pm— 8:30pm— Holy Land - Mixology Alone Erev Shabbat Havdalah w/ Jerusalem II Masterclass 7:30pm— Services the Bar-Lev Marc Rossio in Family Concert 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 7pm— 10:30am— 10:30am— 10:30am— 9:30am— 10am— Acting Masterclass TBS Town Boker Tov 12pm— Parshat Shabbat Songs Sydney Hall - 12pm— Lunch Bunch HaShavua w/ Marc Bering FA COVID-19 Live From The 4:30pm— 4:30pm— 6:30pm— 8:30pm— Holy Land - Healing Service Quarantining Drive-In Havdalah w/ Gaza 7:30pm— Alone Shabbat the Bar-Lev Mixology Masterclass Family 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 10:30am— 10:30am— 10:30am— 9:30am— 8:30pm— Boker Tov Acting Parshat Shabbat Songs Havdalah w/ 11:30am— Masterclass HaShavua w/ Marc the Bar-Lev Lunch & Learn 7:30pm— 6:30pm— Family 30 31 7:30pm— B.R.E.A.D 10:30am— Erev Shabbat Mixology Meeting Services Organization Masterclass Tips & Tricks 5 TBS CONNECT DESCRIPTIONS Havdalah with the Bar-Lev Family - Join the chaos as we say goodbye to Shabbat and welcome in the coming week. -

Israel Hasbara Committee 01/12/2009 20:53

Israel Hasbara Committee 01/12/2009 20:53 Updated 27 November 2008 Not logged in Please click here to login or register Alphabetical List of Authors (IHC News, 23 Oct. 2007) Aaron Hanscom Aaron Klein Aaron Velasquez Abraham Bell Abraham H. Miller Adam Hanft Addison Gardner ADL Aish.com Staff Akbar Atri Akiva Eldar Alan Dershowitz Alan Edelstein Alan M. Dershowitz Alasdair Palmer Aleksandra Fliegler Alexander Maistrovoy Alex Fishman Alex Grobman Alex Rose Alex Safian, PhD Alireza Jafarzadeh Alistair Lyon Aluf Benn Ambassador Dan Gillerman Ambassador Dan Gillerman, Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations AMCHA American Airlines Pilot - Captain John Maniscalco Amihai Zippor Amihai Zippor. Ami Isseroff Amiram Barkat Amir Taheri Amnon Rubinstein Amos Asa-el Amos Harel Anav Silverman Andrea Sragg Simantov Andre Oboler Andrew Higgins Andrew Roberts Andrew White Anis Shorrosh Anne Bayefsky Anshel Pfeffer Anthony David Marks Anthony David Marks and Hannah Amit AP and Herb Keinon Ari Shavit and Yuval Yoaz Arlene Peck Arnold Reisman Arutz Sheva Asaf Romirowsky Asaf Romirowsky and Jonathan Spyer http://www.infoisrael.net/authors.html Page 1 of 34 Israel Hasbara Committee 01/12/2009 20:53 Assaf Sagiv Associated Press Aviad Rubin Avi Goldreich Avi Jorisch Avraham Diskin Avraham Shmuel Lewin A weekly Torah column from the OU's Torah Tidbits Ayaan Hirsi Ali Azar Majedi B'nai Brith Canada Barak Ravid Barry Rubin Barry Shaw BBC BBC News Ben-Dror Yemini Benjamin Weinthal Benny Avni Benny Morris Berel Wein Bernard Lewis Bet Stephens BICOM Bill Mehlman Bill Oakfield Bob Dylan Bob Unruh Borderfire Report Boris Celser Bradley Burston Bret Stephens BRET STEPHENS Bret Stevens Brian Krebs Britain Israel Communications Research Center (BICOM) British Israel Communications & Research Centre (BICOM) Brooke Goldstein Brooke M. -

Miquaot: Ritual Immersion Baths in Second Temple (Intertestamental) Jewish History

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 36 Issue 3 Article 20 7-1-1996 Miquaot: Ritual Immersion Baths in Second Temple (Intertestamental) Jewish History Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Ricks, Stephen D. (1996) "Miquaot: Ritual Immersion Baths in Second Temple (Intertestamental) Jewish History," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 36 : Iss. 3 , Article 20. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol36/iss3/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ricks: <em>Miquaot</em>: Ritual Immersion Baths in Second Temple (Intert miqvaotmiqvaok ritual immersion baths in second temple testamentalInterintertestamental jewish history stephen D ricks one of the most intriguing developments in the archaeology of the second temple testamentalinterintertestamental period of judaism oc- curred during excavations supervised by yigael badinyadin and other archaeologists at masada the residence built for king herod the great while excavating the south casemate wall at masada these archaeologists came upon three structures that looked like a jew- ish ritual bath complex a small pool a medium sized pool and a large pool during a routine press conference it was announced that a possible jewish -

A History of Congregation Beth Yam 1978 -2007 Michael Fritz Robert Pascal Updated by Joseph Levy and Michael Werner 2008

A History of Congregation Beth Yam 1978 -2007 Michael Fritz Robert Pascal Updated by Joseph Levy and Michael Werner 2008 - 2014 1 2 Table of Contents – 1978 - 2007 Book One ...... Genesis – The Beginning ........................................................................................... 1978-1985 Book Two ..... Exodus – From the First Presbyterian Church to our own Sanctuary .... 1985-1990 Book Three .. Leviticus -Priests Four Rabbis ................................................................................ 1990-2002 Book Four .... Numbers -Counting and Census / One Rabbi and Four Presidents ......... 2002-2007 Book Five ..... Deuteronomy -The Repeated/ Second Law - Temple Expansion ......................... 2007 BOOK ONE Genesis 1978 - 1985 In the beginning the Jews of Hilton Head were few and scattered and were without form. Jews had come to visit, but developers did not encourage settlement. Nevertheless, the first Jewish wedding took place on August 24, 1974. The marriage of Cosimo and Deborah Urato was officiated by retired army chaplain, Rabbi Norman Goldberg, and the largest gathering of Jews to date was recorded at the Hilton Head Inn. By the end of the 1970s Jewish settlers did not know whether there were any others here. Some were reluctant to be publicly recognized as Jews and, although they did not deny their faith, neither did they display a mezuzah or other symbol of Jewishness. Nonetheless, thirty people gathered for a Passover dinner in 1979, and the seeds of a Jewish association were sowed. Knowing that there were Jews living in Sea Pines and concerned that there was no synagogue on Hilton Head, the pastor of Christ Lutheran Church voiced this concern to his neighbors and friends, Sue and Hank Noble. In 1980 a notice was placed in the Island Packet inviting all Jews in the area to share a Rosh Hashanah dinner at Christ Lutheran Church. -

Temple Beth Shalom’S Community, Especially Religious School, Played a Key Part in Forming Their Jewish Identity

4 Upcoming Events 6 The Buzz 8 Chai-er Learning 10 Cantorial Corner 11 The Directive 12 Simcha Station 14 WBS & Men’s Club 15 Presidential Address 16 Donor Board Update 18 High Holy Days 20 Donations 21 Yahrzeits 22 Mitzvah Corps Corner 4 August Events Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 6:30pm— 10am— First Friday Outdoor Erev Shabbat Shabbat Service & Services Dinner (Sprinkler Shabbat) 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1pm— 6:30pm— 10am— Mah Jongg Erev Shabbat Outdoor 7pm— Services Shabbat Mahj After Services Dark 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9am— 1pm— 6:30pm— 10am— TBS BIG Ride @ Mah Jongg Shabbat Chai First Aliyah of Trek on Hanah Rogovin Maxtown Rd. 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 10am— 11:30am— 1pm— 6:30pm— 10am— Teacher WBS Lunch & Mah Jongg Erev Shabbat Outdoor Orientation Learn 7pm— Services Shabbat 4pm— 7:30pm— Mahj After Services Board Meeting Choir Dark Rehearsal 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 9:15am— 7:30pm— 1pm— 12pm— 6:30pm— 10am— Yiddish Club Choir Mah Jongg Lunch Bunch Erev Shabbat First Aliyah of 1pm— Rehearsal Service Maya & Ian Teacher Phillips Planning 7pm— 5pm— Jewdies @ TBS Picnic Rockmill Tavern 5 6 The Buzz with Rabbi B The Act of Showing Up: Understanding How to Pay a Shiva Call In the course of studying to become a rabbi, often rabbinic students will serve small congregations around the country who do not have a full or part-time rabbi to serve them. These congregations are often in small towns, where the Jewish population has dwindled throughout the years. -

Worship Prayer at Stern Elana Raskas, P

Volume VI, Issue 3 Winter Break, December 26, 2012 13 Tevet 5773 Kol Hamevaser The Jewish Thought Magazine of the Yeshiva University Student Body Our Side of the Mehitsah: An Open Letter Davida Kollmar, p. 3 Creating Community: WORSHIP Prayer at Stern Elana Raskas, p. 5 Worship: For Us or for Him? Yakov Danishefsky, p. 6 An Interview with Rabbi Ronald Schwarzberg Chesky Kopel, p. 10 The Role of the Sheliah Tsibbur: A Historical Perspective Dovi Nadel, p. 11 “This is My Lord and I Will Beautify Him”: From the Beth Alpha Synagogue to Synagogue in Safed Atara Siegel, p. 17 Creative Arts Section P. 18-19 www.kolhamevaser.com Kol Hamevaser EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Gabrielle Hiller The Jewish Thought Magazine of Chesky Kopel the Yeshiva University Student Body Worship Our Side of the Mehitsah: An Open Letter 3 ASSOCIATE EDITORS A call for common sense: Make women feel comfortable in shul. Adam Friedmann Davida Kollmar KOL HAMEVASER KOL Chumie Yagod Creating Community: Prayer at Stern 5 The Stern community would gain immeasurably from communal davening. So if not now, when? COPY EDITOR Elana Raskas Ze’ev Sudry Worship: For Us or for Him? 6 Why should we worship God? DESIGN EDITOR Yakov Danishefsky Gavriel Brown Patriarchs and Sacrifices: The Philosophical Backing to Prayer 9 Perhaps the argument in the Gemara about the basis for prayer can shed light on the ideal mode of worship. STAFF WRITERS Gilad Barach Sarah Robinson Jacob Bernstein An Interview with Rabbi Ronald Schwarzberg 10 Aaron Cherniak Rabbi Ronald Schwarzberg discusses his role in rabbinic placement, and how his twenty-five years of experience as a Mati Engel pulpit rabbi have informed that role. -

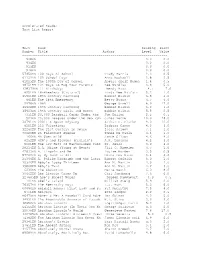

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value 908EN 0.0 0.0 934EN 0.0 0.0 913EN 0.0 0.0 916EN 0.0 0.0 57450EN 100 Days of School Trudy Harris 2.3 0.5 61130EN 100 School Days Anne Rockwell 2.8 0.5 41025EN The 100th Day of School Angela Shelf Medea 1.4 0.5 18751EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 3.9 5.0 128370EN 11 Birthdays Wendy Mass 4.1 7.0 8251EN 18Wheelers (Cruisin') Linda Lee Maifair 5.2 1.0 15901EN 18th Century Clothing Bobbie Kalman 5.8 1.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 15902EN 19th Century Clothing Bobbie Kalman 6.0 1.0 15903EN 19th Century Girls and Women Bobbie Kalman 5.5 0.5 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Jon Buller 2.5 0.5 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 9.0 12.0 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 4.0 1.0 12260EN The 21st Century in Space Isaac Asimov 7.1 1.0 30629EN 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola 4.4 1.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4.0 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups (Cruisin') A.K. Donahue 4.2 1.0 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 4.0 1.0 29214EN A.A. -

Title of Paper

SHOFAR, SALPINX, AND THE SILVER TRUMPETS: THE PURSUIT FOR BIBLICAL CLARITY ______________________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of The School of Church Music and Worship Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary Ft. Worth, Texas _______________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by John Francis September 2020 Copyright © 2020 John Francis All rights reserved. Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. א שֵֽ ֵֽת־חַ֭ יִלֵֽמִ ִ֣ יֵֽיִמְצָָ֑אֵֽוְרָ ח ֹ֖קֵֽמִפְנִינִִ֣יםֵֽמִכְרָ ּה׃ֵֽ To Kimberly ABSTRACT SHOFAR, SALPINX, AND THE SILVER TRUMPETS: THE PURSUIT FOR BIBLICAL CLARITY The trumpet is the most mentioned instrument in the Old and New Testaments. However, because of the lack of specificity in translation, the word “trumpet” in the Bible is oftentimes assumed to be shofar in its derivation when it may be chatsoserot (silver trumpets) or even salpinx (Greek New Testament trumpet). This generalization may lead from mere confusion to full doctrinal misconceptions. This study seeks to clarify these misunderstandings by examining the different trumpets in Scripture: the shofar, the chatsoserot, and the salpinx. I will use this examination to argue that the shofar, though lauded by both Jews and Christians, is not a sacred instrument according to the Bible, but that the chatsoserot was, and the salpinx will be. Furthermore, I demonstrate that the shofar’s now sanctified existence is ostensibly talmudic. After an introductory chapter, chapter 2 details that the shofar currently has an inordinate amount of prestige among both the Jewish people and charismatic Christians. -

Inter Jewish History

miqvaotmiqvaok ritual immersion baths in second temple testamentalInterintertestamental jewish history stephen D ricks one of the most intriguing developments in the archaeology of the second temple testamentalinterintertestamental period of judaism oc- curred during excavations supervised by yigael badinyadin and other archaeologists at masada the residence built for king herod the great while excavating the south casemate wall at masada these archaeologists came upon three structures that looked like a jew- ish ritual bath complex a small pool a medium sized pool and a large pool during a routine press conference it was announced that a possible jewish ritual bath a miqveh had been uncov- ered news of this discovery spread quickly throughout israel par- ticulticularlyarly in the very orthodox hasidic community badinyadin received word that rabbi david muntzbergMuntzberg an expert on jewish miqvaot and author of a study on the subject I1 and rabbi eliezer alter another expert on miqvaot wished to examine the miqveh installation at masada badinyadin replied that he would be happy to receive them one intensely hot day rabbi Muntmuntzbergzberg and rabbi alter arrived at the base of masada without stopping to rest the rabbis and their entourage slowly labored up the steep snake path on the western side of masada in the torrid heat in their heavy hasidic garb when rabbis muntzbergMuntzberg and alter arrived at the summit they asked to be led directly to the miqveh installa- tions armed with a tape measure rabbi Muntmuntzbergzberg went directly