The Benthic Ecology of Some Ria Formosa Lagoons, With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conservation Palaeobiological Approach to Assess Faunal Response of Threatened Biota Under Natural and Anthropogenic Environmental Change

Biogeosciences, 16, 2423–2442, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-2423-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. A conservation palaeobiological approach to assess faunal response of threatened biota under natural and anthropogenic environmental change Sabrina van de Velde1,*, Elisabeth L. Jorissen2,*, Thomas A. Neubauer1,3, Silviu Radan4, Ana Bianca Pavel4, Marius Stoica5, Christiaan G. C. Van Baak6, Alberto Martínez Gándara7, Luis Popa7, Henko de Stigter8,2, Hemmo A. Abels9, Wout Krijgsman2, and Frank P. Wesselingh1 1Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, the Netherlands 2Palaeomagnetic Laboratory “Fort Hoofddijk”, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 17, 3584 CD Utrecht, the Netherlands 3Department of Animal Ecology & Systematics, Justus Liebig University, Heinrich-Buff-Ring 26–32 IFZ, 35392 Giessen, Germany 4National Institute of Marine Geology and Geoecology (GeoEcoMar), 23–25 Dimitrie Onciul St., 024053 Bucharest, Romania 5Department of Geology, Faculty of Geology and Geophysics, University of Bucharest, Balcescu˘ Bd. 1, 010041 Bucharest, Romania 6CASP, West Building, Madingley Rise, Madingley Road, CB3 0UD, Cambridge, UK 7Grigore Antipa National Museum of Natural History, Sos. Kiseleff Nr. 1, 011341 Bucharest, Romania 8NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, Department of Ocean Systems, 1790 AB Den Burg, the Netherlands 9Department of Geosciences and Engineering, Delft University of Technology, Stevinweg 1, 2628 CN Delft, the Netherlands *These authors contributed equally to this work. Correspondence: Sabrina van de Velde ([email protected]) and Elisabeth L. Jorissen ([email protected]) Received: 10 January 2019 – Discussion started: 31 January 2019 Revised: 26 April 2019 – Accepted: 16 May 2019 – Published: 17 June 2019 Abstract. -

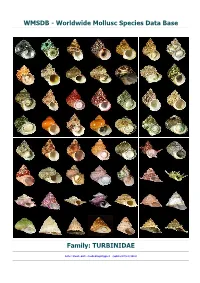

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Phylum MOLLUSCA

285 MOLLUSCA: SOLENOGASTRES-POLYPLACOPHORA Phylum MOLLUSCA Class SOLENOGASTRES Family Lepidomeniidae NEMATOMENIA BANYULENSIS (Pruvot, 1891, p. 715, as Dondersia) Occasionally on Lafoea dumosa (R.A.T., S.P., E.J.A.): at 4 positions S.W. of Eddystone, 42-49 fm., on Lafoea dumosa (Crawshay, 1912, p. 368): Eddystone, 29 fm., 1920 (R.W.): 7, 3, 1 and 1 in 4 hauls N.E. of Eddystone, 1948 (V.F.) Breeding: gonads ripe in Aug. (R.A.T.) Family Neomeniidae NEOMENIA CARINATA Tullberg, 1875, p. 1 One specimen Rame-Eddystone Grounds, 29.12.49 (V.F.) Family Proneomeniidae PRONEOMENIA AGLAOPHENIAE Kovalevsky and Marion [Pruvot, 1891, p. 720] Common on Thecocarpus myriophyllum, generally coiled around the base of the stem of the hydroid (S.P., E.J.A.): at 4 positions S.W. of Eddystone, 43-49 fm. (Crawshay, 1912, p. 367): S. of Rame Head, 27 fm., 1920 (R.W.): N. of Eddystone, 29.3.33 (A.J.S.) Class POLYPLACOPHORA (=LORICATA) Family Lepidopleuridae LEPIDOPLEURUS ASELLUS (Gmelin) [Forbes and Hanley, 1849, II, p. 407, as Chiton; Matthews, 1953, p. 246] Abundant, 15-30 fm., especially on muddy gravel (S.P.): at 9 positions S.W. of Eddystone, 40-43 fm. (Crawshay, 1912, p. 368, as Craspedochilus onyx) SALCOMBE. Common in dredge material (Allen and Todd, 1900, p. 210) LEPIDOPLEURUS, CANCELLATUS (Sowerby) [Forbes and Hanley, 1849, II, p. 410, as Chiton; Matthews. 1953, p. 246] Wembury West Reef, three specimens at E.L.W.S.T. by J. Brady, 28.3.56 (G.M.S.) Family Lepidochitonidae TONICELLA RUBRA (L.) [Forbes and Hanley, 1849, II, p. -

Worms - World Register of Marine Species 15/01/12 08:52

WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species 15/01/12 08:52 http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxlist WoRMS Taxon list http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxlist 405 matching records, showing records 1-100. Rissoa Freminville in Desmarest, 1814 Rissoa aartseni Verduin, 1985 Rissoa aberrans C. B. Adams, 1850 accepted as Stosicia aberrans (C. B. Adams, 1850) Rissoa albella Lovén, 1846 accepted as Pusillina sarsii (Lovén, 1846) Rissoa albella Alder, 1844 accepted as Rissoella diaphana (Alder, 1848) Rissoa albella rufilabrum Alder accepted as Rissoa lilacina Récluz, 1843 Rissoa albugo Watson, 1873 Rissoa alifera Thiele, 1925 accepted as Hoplopteron alifera (Thiele, 1925) Rissoa alleryi (Nordsieck, 1972) Rissoa angustior (Monterosato, 1917) Rissoa atomus E. A. Smith, 1890 Rissoa auriformis Pallary, 1904 Rissoa auriscalpium (Linnaeus, 1758) Rissoa basispiralis Grant-Mackie & Chapman-Smith, 1971 † accepted as Diala semistriata (Philippi, 1849) Rissoa boscii (Payraudeau, 1826) accepted as Melanella polita (Linnaeus, 1758) Rissoa calathus Forbes & Hanley, 1850 accepted as Alvania beanii (Hanley in Thorpe, 1844) Rissoa cerithinum Philippi, 1849 accepted as Cerithidium cerithinum (Philippi, 1849) Rissoa coriacea Manzoni, 1868 accepted as Talassia coriacea (Manzoni, 1868) Rissoa coronata Scacchi, 1844 accepted as Opalia hellenica (Forbes, 1844) Rissoa costata (J. Adams, 1796) accepted as Manzonia crassa (Kanmacher, 1798) Rissoa costulata Alder, 1844 accepted as Rissoa guerinii Récluz, 1843 Rissoa crassicostata C. B. Adams, 1845 accepted as Opalia hotessieriana (d’Orbigny, 1842) Rissoa cruzi Castellanos & Fernández, 1974 accepted as Alvania cruzi (Castellanos & Fernández, 1974) Rissoa cumingii Reeve, 1849 accepted as Rissoina striata (Quoy & Gaimard, 1833) Rissoa curta Dall, 1927 Rissoa decorata Philippi, 1846 Rissoa deformis G.B. -

The Evolution of the Molluscan Biota of Sabaudia Lake: a Matter of Human History

SCIENTIA MARINA 77(4) December 2013, 649-662, Barcelona (Spain) ISSN: 0214-8358 doi: 10.3989/scimar.03858.05M The evolution of the molluscan biota of Sabaudia Lake: a matter of human history ARMANDO MACALI 1, ANXO CONDE 2,3, CARLO SMRIGLIO 1, PAOLO MARIOTTINI 1 and FABIO CROCETTA 4 1 Dipartimento di Biologia, Università Roma Tre, Viale Marconi 446, I-00146 Roma, Italy. 2 IBB-Institute for Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Center for Biological and Chemical Engineering, Instituto Superior Técnico (IST), 1049-001, Lisbon, Portugal. 3 Departamento de Ecoloxía e Bioloxía Animal, Universidade de Vigo, Lagoas-Marcosende, Vigo E-36310, Spain. 4 Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Villa Comunale, I-80121 Napoli, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: The evolution of the molluscan biota in Sabaudia Lake (Italy, central Tyrrhenian Sea) in the last century is hereby traced on the basis of bibliography, museum type materials, and field samplings carried out from April 2009 to Sep- tember 2011. Biological assessments revealed clearly distinct phases, elucidating the definitive shift of this human-induced coastal lake from a freshwater to a marine-influenced lagoon ecosystem. Records of marine subfossil taxa suggest that previous accommodations to these environmental features have already occurred in the past, in agreement with historical evidence. Faunal and ecological insights are offered for its current malacofauna, and special emphasis is given to alien spe- cies. Within this framework, Mytilodonta Coen, 1936, Mytilodonta paulae Coen, 1936 and Rissoa paulae Coen in Brunelli and Cannicci, 1940 are also considered new synonyms of Mytilaster Monterosato, 1884, Mytilaster marioni (Locard, 1889) and Rissoa membranacea (J. -

Inventario De Los Moluscos Y Poliquetos Asociados a Las

Bol. R. Soc. Esp. Hist. Nat. Sec. Biol., 106, 2012, 113-126. ISSN: 0366-3272 Inventario de los moluscos y poliquetos asociados a las praderas de Zostera marina y Zostera noltei de la Ensenada de O Grove (Galicia, N-O España) Check-list of molluscs and polychaetes associated to the Zostera marina and Zostera noltei meadows in the Ensenada de O Grove (Galicia, NW Spain) Patricia Quintas 1*, Eva Cacabelos 2 y Jesús S.Troncoso 1 1. Departamento de Ecoloxía e Bioloxía Animal, Facultade de Ciencias, Campus Lagoas-Marcosende s/n, Universidade de Vigo, E-36210, Vigo, España. *[email protected] 2. Centro Tecnológico del Mar-Fundación CETMAR, C/ Eduardo Cabello s/n, 36208, Vigo, España. Recibido: 23-abril-2012. Aceptado: 5-junio-2012. Publicado en formato electrónico: 30-junio-2012. PALABRAS CLAVE: Inventario, Moluscos, Poliquetos, Praderas de fanerógamas, Zostera marina, Zostera noltei, Ensenada de O Grove, España KEY WORDS: Check-list, Molluscs, Polychaetes, Seagrass, Zostera marina, Zostera noltei, Ensenada de O Grove, Spain RESUMEN Se aporta el inventario de los moluscos y anélidos poliquetos encontrados en los fondos colonizados por Zostera marina L. y Zostera noltei Hornemann de la Ensenada de O Grove (Galicia, NO España). Los muestreos incluyeron un estudio espacial, en el que se muestrearon 10 estaciones con una draga Van-Veen (noviembre 1996), y un estudio temporal, en el que se realizaron inmersiones bimensuales con escafandra autónoma (mayo 1998-marzo 1999) en una estación. Durante el estudio espacial, se contabilizaron 158 taxones, siendo dominante el grupo de los poliquetos (91 taxones) frente al de los moluscos (67 taxones). -

Composition and Structure of the Molluscan Assemblage Associated with a Cymodocea Nodosa Bed in South-Eastern Spain: Seasonal and Diel Variation

Helgol Mar Res (2012) 66:585–599 DOI 10.1007/s10152-012-0294-3 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Composition and structure of the molluscan assemblage associated with a Cymodocea nodosa bed in south-eastern Spain: seasonal and diel variation Pablo Marina • Javier Urra • Jose´ L. Rueda • Carmen Salas Received: 16 May 2011 / Revised: 20 January 2012 / Accepted: 24 January 2012 / Published online: 11 February 2012 Ó Springer-Verlag and AWI 2012 Abstract The molluscan taxocoenosis associated with a March and June. Shannon–Wiener diversity (H0) values Cymodocea nodosa seagrass bed was studied throughout were generally higher in nocturnal samples than in diurnal 1 year in Genoveses Bay, in the MPA ‘‘Parque Natural ones, displaying minimum values in December and June, Cabo de Gata-Nı´jar’’ (south-eastern Spain). A total of respectively. Evenness was similar in diurnal and nocturnal 64,824 individuals were collected and 54 species identified. samples, with maximum values in July in both groups. The molluscan fauna was mainly composed of gastropods S and H0 were also significantly different between diurnal (99.56% of individuals, 43 spp.). The families Rissoidae and nocturnal samples. Multivariate analyses based on both (72.98%, 11 spp.) and Trochidae (16.93%, 7 spp.) were the qualitative and quantitative data showed a significant sea- most abundant and diversified in terms of number of spe- sonal and diel variation. Diel changes revealed to be more cies. Rissoa monodonta (47.1% dominance), Rissoa mem- distinct than seasonal ones. branacea (25.1%) and Gibbula leucophaea (11.6%) proved the top dominant species in both diurnal and nocturnal Keywords Molluscs Á Seasonal dynamics Á Diel samples. -

The Sound Biodiversity, Threats, and Transboundary Protection.Indd

2017 The Sound: Biodiversity, threats, and transboundary protection 2 Windmills near Copenhagen. Denmark. © OCEANA/ Carlos Minguell Credits & Acknowledgments Authors: Allison L. Perry, Hanna Paulomäki, Tore Hejl Holm Hansen, Jorge Blanco Editor: Marta Madina Editorial Assistant: Ángeles Sáez Design and layout: NEO Estudio Gráfico, S.L. Cover photo: Oceana diver under a wind generator, swimming over algae and mussels. Lillgrund, south of Øresund Bridge, Sweden. © OCEANA/ Carlos Suárez Recommended citation: Perry, A.L, Paulomäki, H., Holm-Hansen, T.H., and Blanco, J. 2017. The Sound: Biodiversity, threats, and transboundary protection. Oceana, Madrid: 72 pp. Reproduction of the information gathered in this report is permitted as long as © OCEANA is cited as the source. Acknowledgements This project was made possible thanks to the generous support of Svenska PostkodStiftelsen (the Swedish Postcode Foundation). We gratefully acknowledge the following people who advised us, provided data, participated in the research expedition, attended the October 2016 stakeholder gathering, or provided other support during the project: Lars Anker Angantyr (The Sound Water Cooperation), Kjell Andersson, Karin Bergendal (Swedish Society for Nature Conservation, Malmö/Skåne), Annelie Brand (Environment Department, Helsingborg municipality), Henrik Carl (Fiskeatlas), Magnus Danbolt, Magnus Eckeskog (Greenpeace), Søren Jacobsen (Association for Sensible Coastal Fishing), Jens Peder Jeppesen (The Sound Aquarium), Sven Bertil Johnson (The Sound Fund), Markus Lundgren -

Rissoa Membranacea (J. Adams, 1800)

Rissoa membranacea (J. Adams, 1800) AphiaID: 141359 . Animalia (Reino) > Mollusca (Filo) > Gastropoda (Classe) > Caenogastropoda (Subclasse) > Littorinimorpha (Ordem) > Rissooidea (Superfamilia) > Rissoidae (Familia) Natural History Museum Rotterdam Natural History Museum Rotterdam Sinónimos Alvania plicatula Risso, 1826 Helix labiosa Montagu, 1803 Rissoa brunosericea Smagowicz, 1977 Rissoa elata Philippi, 1844 Rissoa fragilis Michaud, 1830 Rissoa grossa Michaud, 1830 Rissoa grossa var. elatopsis Mars, 1956 1 Rissoa grossa var. plicacea “Monterosato” Mars, 1956 Rissoa labiosa (Montagu, 1803) Rissoa membranacea var. cornea (Lovén, 1846) Rissoa membranacea var. gracilis (Forbes & Hanley, 1850) Rissoa membranacea var. labiosa (Montagu, 1803) Rissoa membranacea var. minor Jeffreys, 1867 Rissoa membranacea var. octona auct. non Linnaeus, 1767 Rissoa oblonga Desmarest, 1814 Rissoa pontica Milaschewitsch, 1916 Rissoa venusta var. pontica Milaschewich, 1916 Rissostomia membranacea (J. Adams, 1800) Rissostomia membranacea cornea (Lovén, 1846) Rissostomia membranacea labiosa (Montagu, 1803) Rissostomia membranacea octona auct. non Linnaeus, 1767 Turbo membranaceus J. Adams, 1800 Turboella (Nititurboella) cornea (Lovén, 1846) Zippora membranacea (J. Adams, 1800) Zippora membranacea (J. Adams, 1800) Referências additional source Backeljau, T. (1986). Lijst van de recente mariene mollusken van België [List of the recent marine molluscs of Belgium]. Koninklijk Belgisch Instituut voor Natuurwetenschappen: Brussels, Belgium. 106 pp. [details] basis of record Gofas, S.; Le Renard, J.; Bouchet, P. (2001). Mollusca. in: Costello, M.J. et al. (eds), European Register of Marine Species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Patrimoines Naturels. 50: 180-213. [details] additional source Muller, Y. (2004). Faune et flore du littoral du Nord, du Pas-de-Calais et de la Belgique: inventaire. -

(J. Adams, 1800) (Gastropoda, Prosobranchia) from the Dutch Wadden Sea

BASTERIA, Vol. 61: 89-98, 1998 Rissoa membranacea (J. Adams, 1800) (Gastropoda, Prosobranchia) from the Dutch Wadden Sea Gerhard+C. Cadée Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, P.O. Box 59, 1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands Rissoa membranacea disappeared from the Dutch Wadden Sea together with the large subtidal stands L. ofeelgrass Zostera marina in the early 1930s, due to a still not completely understood ‘wasting disease’ in Zostera. A small population of R. membranacea survived together with Zostera marina in inland Bol’ 1981. shells of R. an brackish water ‘de on Texel until Empty membranacea can still be found at these localities. The relatively large size of the top-whorl ofWadden Sea R. membranacea indicates that the larvae In this were lecithotrophic. respect they arecomparable to R. membranacea type B from the Roskilde Fjord of Rehfeldt (1968) and Warén (1996) and R. membranacea to s.s. as described by Verduin (1982b). It is, however, questionablewhether R. membranacea Type A ofRehfeldt and R. labiosa sensu Verduin can be separated from R. membranacea s.s. They differ only in the smaller size of the embryonic whorl indicating planktothrophic larvae. This well indicate different oflarval pelagic might as two types development,lecithotrophic andplanktotrophic in one and the same species R. membranacea s.l. Apical dimensions in samples from the Ria de Arosa (Spain) and from Dutch Eemian deposits show a gradual change from small ‘R. labiosa’ to larger ‘R. membranacea’ values, which supports the merging ofboth nominal species and corroborates Warén’s suggestion of a continuum in larval development in R. -

(Zostera Marina L.) in the Alboran Sea: Micro-Habitat Preference, Feeding Guilds and Biogeographical Distribution

SCIENTIA MARINA 73(4) December 2009, 679-700, Barcelona (Spain) ISSN: 0214-8358 doi: 10.3989/scimar.2009.73n4679 A highly diverse molluscan assemblage associated with eelgrass beds (Zostera marina L.) in the Alboran Sea: Micro-habitat preference, feeding guilds and biogeographical distribution JOSÉ L. RUEDA, SERGE GOFAS, JAVIER URRA and CARMEN SALAS Departamento de Biología Animal, Universidad de Málaga, Campus de Teatinos s/n, 29071 Málaga, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: The fauna of molluscs associated with deep subtidal Zostera marina beds (12-16 m) in southern Spain (Albo- ran Sea) has been characterised in terms of micro-habitat preference, feeding guilds and biogeographical affinity. The species list (162 taxa) is based on sampling completed before the strong eelgrass decline experienced in 2005-2006, using different methods (small Agassiz trawl covering 222 m2 and quadrates covering 0.06 m2) and different temporal scales (months, day/night). Dominant epifaunal species are Jujubinus striatus, Rissoa spp. and Smaragdia viridis in the leaf stratum and Nassarius pygmaeus, Bittium reticulatum and Calliostoma planatum on the sediment. Nevertheless, the infauna dominated the epifauna in terms of number of individuals, including mainly bivalves (Tellina distorta, T. fabula, Dosinia lupinus). The epifauna of both the sediment and leaf strata included high numbers of species, probably due to the soft transition between vegetated and unvegetated areas. The dominant feeding guilds were deposit feeders, filter feeders and peryphiton grazers, but ectoparasites (eulimids), seagrass grazers (Smaragdia viridis) and an egg feeder (Mitrella minor) also occurred, unlike in other eelgrass beds of Europe. The molluscan fauna of these Z. -

Stratigraphic Paleobiology of Late Quaternary Mollusk Assemblages from the Po Plain-Adriatic Sea System

Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN SCIENZE DELLA TERRA DELLA VITA E DELL’AMBIENTE Ciclo XXXI Settore concorsuale: 04/A2 Settore Scientifico disciplinare: GEO/01 Stratigraphic paleobiology of late Quaternary mollusk assemblages from the Po Plain-Adriatic Sea system Presentata da: Michele Azzarone Coordinatore Dottorato: Supervisore: Prof. Giulio Viola Dott.Daniele Scarponi Esame Finale anno 2019 Abstract Stratigraphic paleobiology - a relatively new approach for investigating fossiliferous sedimentary successions - is rooted on the assumption that the fossil record cannot be read at face value, being controlled not only by biotic, but also by sedimentary processes that control deposition and erosion of sediments. By applying the stratigraphic paleobiology tenets, this Ph.D. project focused on acquisition and analyses of macrofossils data to assess the response of late Quaternary ecosystems to environmental changes and enhance stratigraphic interpretations of fossiliferous successions. A primary activity of my Ph.D. research involved assembling a macrobenthic dataset from the latest Pleistocene glacial succession of the near-Mid Adriatic Deep (Central Adriatic, Italy). This dataset once combined with its counterpart from the Po coastal plain (Holocene), will offer a unique perspective on mollusk faunas and their dynamics during the current glacial-interglacial cycle. This thesis includes four papers. The first one assessed the quality and resolution of the macrofossil record from transgressive Holocene deposits of Po plain (Italy). The second paper focused on the Holocene fossil record of the Po coastal plain to evaluate the response of trematode parasites to high-frequency sea-level oscillations. The third study investigated distribution of last occurrences of macrobenthic species along a down-dip transect in the Po coastal plain and evaluate potential effects of sequence stratigraphic architecture on mass extinction pattern.