Butsch, Five Decades of Sitcom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

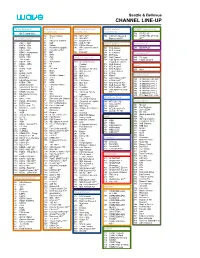

Channel Lineup

Seattle & Bellevue CHANNEL LINEUP TV On Demand* Expanded Content* Expanded Content* Digital Variety* STARZ* (continued) (continued) (continued) (continued) 1 On Demand Menu 716 STARZ HD** 50 Travel Channel 774 MTV HD** 791 Hallmark Movies & 720 STARZ Kids & Family Local Broadcast* 51 TLC 775 VH1 HD** Mysteries HD** HD** 52 Discovery Channel 777 Oxygen HD** 2 CBUT CBC 53 A&E 778 AXS TV HD** Digital Sports* MOVIEPLEX* 3 KWPX ION 54 History 779 HDNet Movies** 4 KOMO ABC 55 National Geographic 782 NBC Sports Network 501 FCS Atlantic 450 MOVIEPLEX 5 KING NBC 56 Comedy Central HD** 502 FCS Central 6 KONG Independent 57 BET 784 FXX HD** 503 FCS Pacific International* 7 KIRO CBS 58 Spike 505 ESPNews 8 KCTS PBS 59 Syfy Digital Favorites* 507 Golf Channel 335 TV Japan 9 TV Listings 60 TBS 508 CBS Sports Network 339 Filipino Channel 10 KSTW CW 62 Nickelodeon 200 American Heroes Expanded Content 11 KZJO JOEtv 63 FX Channel 511 MLB Network Here!* 12 HSN 64 E! 201 Science 513 NFL Network 65 TV Land 13 KCPQ FOX 203 Destination America 514 NFL RedZone 460 Here! 14 QVC 66 Bravo 205 BBC America 515 Tennis Channel 15 KVOS MeTV 67 TCM 206 MTV2 516 ESPNU 17 EVINE Live 68 Weather Channel 207 BET Jams 517 HRTV PayPerView* 18 KCTS Plus 69 TruTV 208 Tr3s 738 Golf Channel HD** 800 IN DEMAND HD PPV 19 Educational Access 70 GSN 209 CMT Music 743 ESPNU HD** 801 IN DEMAND PPV 1 20 KTBW TBN 71 OWN 210 BET Soul 749 NFL Network HD** 802 IN DEMAND PPV 2 21 Seattle Channel 72 Cooking Channel 211 Nick Jr. -

Alphabetical Channel Listing

Alphabetical Channel Listing 129 A&E 131 Discovery Channel 203 FUEL TV 566 MUN2 75 Speed Channel 761 A&E-HD 557 Discovery en Espanol 124 FX 130 National Geographic 141 Spike TV 122 ABC Family 558 Discovery Familia 147 Game Show Network 751 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC-HD 84 Sportsman’s Channel 794 ABC Family-HD 108 Discovery Kids Channel 86 Golf Channel 241 National Geographic Wild 641 STANDARD JAZZ 174 ABC News Now 242 Discovery Health 646 GOSPEL 48 NBC - WAFF Huntsville 800 STARZ E-HD 31 ABC - WAAY Huntsville 98 Disney Channel 202 Great American Country 748 NBC-WAFF Huntsville-HD 402 Starz Cinema E 731 ABC-WAAY Huntsville-HD 795 Disney-HD 128 Hallmark 3 NBC - WRCB Chattanooga 403 Starz Cinema W 9 ABC - WTVC Chattanooga 99 Disney XD 308 Hallmark Movie Channel 703 NBC-WRCB Chattanooga-HD 406 Starz Comedy E 709 ABC-WTVC Chattanooga-HD 796 Disney XD-HD 500 HBO E 101 Nick 2 400 Starz East 653 ACOUSTIC CHILL (MooD) 234 DIY 900 HBO E-HD 658 NICK KIDS 408 Starz Edge E 522 ActionMax 652 MDREA SEQUENCE (MooD) 902 HBO 2 E-HD 100 Nickelodeon/Nick at Nite 410 Starz in Black E 622 ADULT ROCK 240 E! Entertainment TV 508 HBO Comedy 102 NickToons 404 Starz Kids & Family E 621 ALTERNATIVE ROCK 999 EAS (EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM) 506 HBO Family 104 Noggin 804 STARZ Kids & Family E-HD 107 Animal Planet 639 EASY LISTENING 512 HBO Latino 657 NOGGIN 405 Starz Kids & Family W 620 ARENA ROCK 617 ELECTRONICA 502 HBO 2 643 OPERA 401 Starz West 135 BBC America 420 Encore Action E 504 HBO Signature 85 Outdoor Channel 309 Sundance E 136 BBC World News 421 Encore Action W 510 -

A Decade of Deceit How TV Content Ratings Have Failed Families EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Major Findings

A Decade of Deceit How TV Content Ratings Have Failed Families EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Major Findings: In its recent report to Congress on the accuracy of • Programs rated TV-PG contained on average the TV ratings and effectiveness of oversight, the 28% more violence and 43.5% more Federal Communications Commission noted that the profanity in 2017-18 than in 2007-08. system has not changed in over 20 years. • Profanity on PG-rated shows included suck/ Indeed, it has not, but content has, and the TV blow, screw, hell/damn, ass/asshole, bitch, ratings fail to reflect “content creep,” (that is, an bastard, piss, bleeped s—t, bleeped f—k. increase in offensive content in programs with The 2017-18 season added “dick” and “prick” a given rating as compared to similarly-rated to the PG-rated lexicon. programs a decade or more ago). Networks are packing substantially more profanity and violence into youth-rated shows than they did a decade ago; • Violence on PG-rated shows included use but that increase in adult-themed content has not of guns and bladed weapons, depictions affected the age-based ratings the networks apply. of fighting, blood and death and scenes We found that on shows rated TV-PG, there was a of decapitation or dismemberment; The 28% increase in violence; and a 44% increase in only form of violence unique to TV-14 rated profanity over a ten-year period. There was also a programming was depictions of torture. more than twice as much violence on shows rated TV-14 in the 2017-18 television season than in the • Programs rated TV-14 contained on average 2007-08 season, both in per-episode averages and 84% more violence per episode in 2017-18 in absolute terms. -

Socioeconomic Class Representation in Sitcoms Awroa:&~

KEEPING UP WITH THE JONESES: SOCIOECONOMIC CLASS REPRESENTATION IN SITCOMS by ALEXANDRA HICKS A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2014 A• Abstracto( the Thesis of Alexandra Hicks for 1he degree ofBachelor of Arts in the School of Journalism and Communication to be talcen June, 2014 Title: Keeping Up With the Jonescs: Socioeconomic Class Representation in Sitcoms Awroa:&~ This thesis examines the representation of socioeconomic class in situation comedies. Through the influence of the advertising industiy, situation comedies (sitcoms) have developed a pattem throughout history of misrepresenting ~ial class, which is made evident by their portrayals ofdifferent races, genders, and professions. To rectify the IKk ofprevious studies on modem comedies, this study analyzes socioeconomic class representation on sitcoms that have aired in the last JS years by taking a sample ofseven shows and comparing the estimated cost of characters' residences to the amount of money they would likely earn in their given profession. 1be study showed that modem situation comedies misrepresent socioeconomic class by portraying characters living in residences well beyond what they could afford in real life. Accurate demonstration ofsocioeconomic class on television is imperative be<:ause images presented on television genuinely influence viewers• perceptions of reality. Inaccurate portrayals ofclass could cause audiences to develop distorted views ofmember.; of socioeconomic classes and themselves. u Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Debra Merskin for inspiring me to examine television in an in-depth and critical manner. -

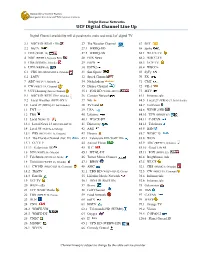

UCF Digital Channel Line Up

University of Central Florida Computer Services and Telecommunications Bright House Networks UCF Digital Channel Line Up Digital Channel availability will depend on the make and model of digital TV. 2.1 NBC HD (WESH 2-HD) 27 The Weather Channel 67 BET 2.2 MeTV 27.1 WRDQ-HD 68 Spike 3 FOX (WOFL 35) 27.2 WRDQ-AN 68.1 WUCF-TV 4 NBC (WESH 2, Daytona Bch) 28 FOX News 68.2 WBCC-TV 5 CBS (WKMG 6, Orlando) 29 ESPN 68.3 UCF-TV 6 UPN (WRBW 65) 30 ESPN2 68.4 WBCC+ 6.1 CBS HD (WKMG-HD 6, Orlando) 31 Sun Sports 69 SyFy 6.2 LATV 32 Speed Channel 70 FX 7 ABC (WFTV 9, Orlando) 34 Nickelodeon 71 CMT 8 CW (WKCF 18, Clermont) 35 Disney Channel 72 VH-1 9 UCF Housing (Movie Channel) 35.1 FOX HD (WOFL-HD 35) 73 MTV 9.1 ABC HD (WFTV-HD 9, Orlando) 36 Cartoon Network 81.1 Infomercials 9.2 Local Weather (WFTV-WX 9) 37 WE 84.5 Local 27 (WRDQ-27, Ind Orlando) 10 Local 27 (WRDQ-27, Ind Orlando) 38 TV Land 84.7 Univision 11 TNT 39 USA 84.8 WESH 2 HD 12 TBS 40 Lifetime 84.10 UPN (WRBW 65) 13 Local News 13 40.1 WACX-DT 84.11 C-SPAN 13.1 Local News 13 HD (CFN-HD 13) 41 Discovery 84.12 Telefutura 14 Local 55 (WACX, Leesburg) 42 A&E 85.5 HSN 15.1 PBS (WCEU-DT 15, Daytona) 43 History 85.7 WDSC 15 15.2 The Florida Channel (DSC-ED) 43.1 Telefutura HD (WOTF-HD) 85.8 WGN 15.3 CCTV 9 44 Animal Planet 85.9 ABC (WFTV 9, Orlando) 15.13 Galavision HD 45 TLC 85.10 Good Life 45 16 ION (WOPX 56, Orlando) 45.1 WTGL-DT 85.11 FOX (WOFL 35) 17 Telefutura (WOTF 43, Melb.) 46 Turner Movie Classics 86.4 Brighthouse Ads 18 Univision (WVEN 26, Orlando) 47.1 BHSN 87.3 WUCF 18.1 CW HD (WKFC-HD -

Page 1 1/26/2018 55 Bravo 447 SEC Network 675 STARZ Cinema East

G R I D L E Y C A B L E S E R V I C E C H A N N E L L I N E U P BASIC 55 Bravo 447 SEC Network 675 STARZ Cinema East 110 Weather Channel HD 2 WEEK-D3, CW, Peoria 56 Lifetime Television 448 FOX Sports 2 676 STARZ Kids & Family East 111 GETTV 3 WEEK-D2, ABC, 19 Peoria 57 USA Network 453 FXX 677 STARZ Comedy East 112 BOUNCE HD 4 WEEK-TV, NBC, 25 Peoria 58 Paramount Network (Spike) 457 FOX Sports 1 Cinemax Multiplex 113 Antenna TV HD 5 WMBD CBS 31 Peoria 59 Comedy Central 458 Discovery Life 600 Cinemax East 114 FOX Sports Midwest PLUS HD 6 WTVP PBS 47 Peoria 60 FX 465 MTV 601 Cinemax West 115 NFL Network HD 7 TBS Superstation 61 TNT 466 MTV2 602 More Max East 116 ESPN HD 8 WYZZ FOX 43 Bloomington 62 Syfy 467 Nick Music 603 More Max West 117 Fox Sports Midwest HD 9 WGN America 63 FXX 468 BET Jams 604 Action Max East 118 Big Ten Network HD 10 WAOE UPN 59 Peoria/Blm 78 E! 470 VH1 605 Thriller Max East 119 NBC Sports Chicago HD 11 The Weather Channel 82 Oxygen 471 MTV Classic Ask about special pricing for 120 NBC Sports Chicago+HD 12 Community Channel 93 OWN 472 BET Soul HBO & Cinemax Combo 121 ESPNU HD 13 CNN 94 Investigation Discovery 474 Fuse Showtime 122 ESPN2 HD 14 Home Shopping Network 475 CMT 650 SHOWTIME East 123 NBCSN HD 15 MSNBC 476 CMT Music 651 SHOWTIME West 124 FS1 HD 16 FOX News Channel Analog Premium 477 Great American Country 652 SHOWTIME 2 East 125 OUT HD 17 FOX Business News 52 STARZ ENCORE 480 TBN Trinity Broadcasting Network 653 SHOWTIME 2 West 130 FBN HD 18 CNBC Digital Channels 490 FX Movie Channel 654 SHOWTIME SHOWCASE -

Basic Plus Cable $93.75

Riviera Cable www.rivierautilities.com Basic Plus Cable $93.75 (104 Channels) 23.3 WSRE World* 55.2 Bounce TV* 2 WEIQ - PBS 42 23.4 WSRE PBS Kids* 55.3 Justice Network* 3 WEAR - ABC 3 25 Lifetime Television 55.4 WFNA GRIT TV* 3.1 WEAR - ABC 3 HD* 26 Home and Garden TV 56 Disney XD 3.2 TBD* 27 Travel Channel 57 Cartoon Network 3.3 CHARGE* 28 WTBS Superstation 58 Animal Planet 4 WSRE - PBS 23 29 TNT 59 Freeform 5 WKRG - CBS 5 30 ESPNU 60 A & E Network 5.1 WKRG - CBS 5 HD* 31 WGN America 61 AMC 5.3 Me TV* 32 EWTN 62 History Channel 5.4 WKRG LAFF TV* 33 ESPN 63 Bravo 6 WFNA - CW 55 33.1 WHBR HD* 64 SyFy 7 Local Weather/WHEP 33.2 WHBR CTNi* 65 Oxygen 7.1 Local Weather/WHEP* 33.3 WHBR LifeStyle TV* 66 E! Entertainment 8 WMPV - TBN 21 34 ESPN2 67 Disney Jr. 9 WJTC - IND 44 35 ESPN Classic 68 Food Network 10 WALA - FOX 10 35.1 WFGX – MYTV 35 HD* 69 Great American Country 10.1 WALA - FOX 10 HD* 35.2 get TV* 70 OWN 10.2 COZI TV* 35.3 COMET TV* 71 C-SPAN2 10.3 WALA LAFF* 36 Fox Sports South 72 The Hallmark Channel 10.4 ESCAPE* 37 National Geographic 73 truTV 11 WPMI - NBC 15 38 Discovery Channel 74 Outdoor Channel 12 QVC 39 The Learning Channel 75 NBC Sports 13 WHBR- CTN 33 40 Fox News Channel 76 SEC Network 14 WFGX – MYTV 35 41 CNN 77 FXX 15 The Weather Channel 42 CNN Headline News 78 Fox Sports 1 15.1 WPMI - NBC 15 HD* 42.1 WEIQ - PBS 42 HD* 79 Investigation Discovery 15.2 WPMI Weather Plus* 42.2 APT Kids* 80 Tennis Channel 15.3 Stadium* 42.3 APT Create* 106.2 QVC HD* 16 Baldwin County 42.4 APT World* 108.3 SEC Rollover* Commission 43 CNBC 110.1 -

WB-AVO Operator's Manual

WB-AVO OPERATOR’S MANUAL Table of Contents 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS In Chapter 1 Contents Features at a Glance iv Chapter 1 Introduction General Information 1 – 1 Features and Configurations 1 – 3 ACAO E02/P01 05/95 OMEGA WB-AVO Operator’s Manual i WB-AVO OPERATOR’S MANUAL In Chapter 2 Contents Chapter 2 Installing the WB-AVO Overview 2 – 1 Verifying WB-AVO Switch Settings 2 – 2 Illustration of the WB-AVO Board 2 – 3 Physical Board Installation 2 – 4 Setting the Voltage/ Current Switches 2 – 6 Setting the Board Number Switches 2 – 8 Setting the Base Address Switches 2 – 10 Table of Contents ii TABLE OF CONTENTS In Chapter 3 Contents Chapter 3 Technical Notes Overview 3 – 1 Pin Assignments for the WB-AVO 3 – 2 Block Diagram 3 – 3 Recalibration 3 – 4 Editing Calibration Files 3 – 5 Calibration File Format (CALOUT.DAT) 3 – 7 Reconstructing A Lost Calibration File 3 – 9 Using EDITCAL 3 – 9 Troubleshooting: Installation 3 – 11` Troubleshooting: Operation 3 – 12 Product Specifications 3 – 14 WB-AVO Operator’s Manual iii WB-AVO OPERATOR’S MANUAL Features at a Glance Highlights of the WB-AVO Analog Output Channels 8: WB-AVO-8 2: WB-AVO-2 Analog Output Resolution 12 bits (.024%) Maximum Output Rate 130 kHz Both Models of the WB-AVO Feature Three voltage output ranges, one current output range Eight Digital I/O lines, user configurable · Factory guaranteed accuracy for two years from date of purchase Front Matter iv INTRODUCTION General Information Chapter 1: Introduction to the ACAO Thank you for selecting the WB-AVO for your project! Our primary objective is to provide you with data acquisition systems that are easy to install, operate, and maintain. -

Xfinity Channel Lineup

Channel Lineup 1-800-XFINITY | xfinity.com SARASOTA, MANATEE, VENICE, VENICE SOUTH, AND NORTH PORT Legend Effective: April 1, 2016 LIMITED BASIC 26 A&E 172 UP 183 QUBO 738 SPORTSMAN CHANNEL 1 includes Music Choice 27 HLN 179 GSN 239 JLTV 739 NHL NETWORK 2 ION (WXPX) 29 ESPN 244 INSP 242 TBN 741 NFL REDZONE <2> 3 PBS (WEDU SARASOTA & VENICE) 30 ESPN2 42 BLOOMBERG 245 PIVOT 742 BTN 208 LIVE WELL (WSNN) 31 THE WEATHER CHANNEL 719 HALLMARK MOVIES & MYSTERIES 246 BABYFIRST TV AMERICAS 744 ESPNU 5 HALLMARK CHANNEL 32 CNN 728 FXX (ENGLISH) 746 MAV TV 6 SUNCOAST NEWS (WSNN) 33 MTV 745 SEC NETWORK 247 THE WORD NETWORK 747 WFN 7 ABC (WWSB) 34 USA 768-769 SEC NETWORK (OVERFLOW) 248 DAYSTAR 762 CSN - CHICAGO 8 NBC (WFLA) 35 BET 249 JUCE 764 PAC 12 9 THE CW (WTOG) 36 LIFETIME DIGITAL PREFERRED 250 SMILE OF A CHILD 765 CSN - NEW ENGLAND 10 CBS (WTSP) 37 FOOD NETWORK 1 includes Digital Starter 255 OVATION 766 ESPN GOAL LINE <14> 11 MY NETWORK TV (WTTA) 38 FOX SPORTS SUN 57 SPIKE 257 RLTV 785 SNY 12 IND (WMOR) 39 CNBC 95 POP 261 FAMILYNET 47, 146 CMT 13 FOX (WTVT) 40 DISCOVERY CHANNEL 101 WEATHERSCAN 271 NASA TV 14 QVC 41 HGTV 102, 722 ESPNEWS 279 MLB NETWORK MUSIC CHOICE <3> 15 UNIVISION (WVEA) 44 ANIMAL PLANET 108 NAT GEO WILD 281 FX MOVIE CHANNEL 801-850 MUSIC CHOICE 17 PBS (WEDU VENICE SOUTH) 45 TLC 110 SCIENCE 613 GALAVISION 17 ABC (WFTS SARASOTA) 46 E! 112 AMERICAN HEROES 636 NBC UNIVERSO ON DEMAND TUNE-INS 18 C-SPAN 48 FOX SPORTS ONE 113 DESTINATION AMERICA 667 UNIVISION DEPORTES <5> 19 LOCAL GOVT (SARASOTA VENICE & 49 GOLF CHANNEL 121 DIY NETWORK 721 TV GAMES 1 includes Limited Basic VENICE SOUTH) 50 VH1 122 COOKING CHANNEL 734 NBA TV 1, 199 ON DEMAND (MAIN MENU) 19 LOCAL EDUCATION (MANATEE) 51 FX 127 SMITHSONIAN CHANNEL 735 CBS SPORTS NETWORK 194 MOVIES ON DEMAND 20 LOCAL GOVT (MANATEE) 55 FREEFORM 129 NICKTOONS 738 SPORTSMAN CHANNEL 299 FREE MOVIES ON DEMAND 20 LOCAL EDUCATION (SARASOTA, 56 AMC 130 DISCOVERY FAMILY CHANNEL 739 NHL NETWORK 300 HBO ON DEMAND VENICE & VENICE SOUTH) 58 OWN 131 NICK JR. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation.