Davenport's Golden Building Years Edmund H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

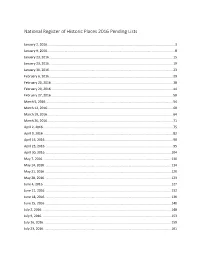

National Register of Historic Places Pending Lists for 2016

National Register of Historic Places 2016 Pending Lists January 2, 2016. ............................................................................................................................................ 3 January 9, 2016. ............................................................................................................................................ 8 January 23, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 15 January 23, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 19 January 30, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 23 February 6, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 29 February 20, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 38 February 20, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 44 February 27, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 50 March 5, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................... -

Uptown Girl: the Andresen Flats and the West End by Marion Meginnis

Uptown Girl: The Andresen Flats and the West End By Marion Meginnis Spring 2015 HP613 Urban History Goucher College M.H.P Program Consistent with the Goucher College Academic Honor Code, I hereby affirm that this paper is my own work, that there was no collaboration between myself and any other person in the preparation of this paper (I.B.1), and that all work of others incorporated herein is acknowledged as to author and source by either notation or commentary (I.B.2). _____________ (signature) ___________ (date) The Andresen Flats The Andresen Flats and its neighborhood are tied to the lives of Davenport, Iowa’s earliest German settlers, people who chose Davenport as a place of political refuge and who gave and demanded much of their new community. At times, their heritage and beliefs would place them on a collision course with fellow citizens with different but equally deeply felt beliefs. The conflicts played out against the backdrop of national events occurring less than a hundred years after the city’s founding and just a few years after the Andresen was built. The changes that followed and the shift in how Davenporters lived in their city forever altered the course of the neighborhood, the building, and the citizens who peopled both. Built by German immigrant H. H. Andresen in 1900, the Flats dominates its corner at Western Avenue and West 3rd Street in downtown Davenport. The city is located at one of the points where the Mississippi River’s flow is diverted from its north/south orientation to run west. -

Directory of Theamerican Society of Certified Public Accountants, December 31, 1934 American Society of Certified Public Accountants

University of Mississippi eGrove American Institute of Certified Public Accountants AICPA Committees (AICPA) Historical Collection 1-1-1934 Directory of theAmerican Society of Certified Public Accountants, December 31, 1934 American Society of Certified Public Accountants Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_comm Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation American Society of Certified Public Accountants, "Directory of theAmerican Society of Certified Public Accountants, December 31, 1934" (1934). AICPA Committees. 148. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_comm/148 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in AICPA Committees by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIRECTORY -----------------------of----------------------- THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS Officers ■ Directors ■ State Representatives ■ Committees Members of State Boards of Accountancy Officers of State Organizations ■ Membership Roster Constitution and By-Laws THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS NATIONAL PRESS BUILDING - WASHINGTON, D. C. DECEMBER 31, 1934 DIRECTORY OF OFFICIALS, 1934-35 OFFICERS STATE REPRESENTATIVES President: William C. Heaton, 207 Broad Alabama—Gilbert F. Dukes, First National Street, Elizabeth, New Jersey. Bank Building, Mobile. First Vice-President: William D. Morrison, Alaska—Erling Johansen, P. O. Box 266, First National Bank Building, Denver, Col Petersburg. orado. Arizona—Alex W. Crane, Heard Building, Second Vice-President: Orion N. Hutchinson, Phoenix. Johnston Building, Charlotte, North Caro lina. Arkansas—Caddie H. Kinard, Armstrong Build ing, El Dorado. Treasurer: Walter D. Wall, 44 West Gay Street, Columbus, Ohio. -

1965, Five Just As in Robert Frost's, "The Road Little Skiing When He Can

KNIGHT BEACON BoostersBring College To Nigl,School We the students of Assumption High resentative to start his presentation at St. Mary's College, Winona, Minnesota; Soon to college must apply a c rtain time for one group of people. and St. Tho mas College, St. Paul, Min We know not where, or how, or when, Fr. Charles Mann, boys' division vice nesota. But that' where College ight comes principal noted, "The system worked Refreshments will be served in the in! well for the colleges that used it last cafeteria during the evening. This year on Wednesday, October y ar, and we hope it will work again 15, at 7:30 Assumption high school's this year." annual College Night will take place . Three new addition are fore. een in A coll ge atmosphere will be enacted this year' chedule. Tho e hool are: when over 40 colleges, universities, The College of t. Benedict, t. Joseph, Knite technical colleges, and nursing colleges linnesota, Loras College, Dubuque, will send representatives to the event. Iowa, and Edgewood College of the acred Heart, Madison, Wi consin. Lite Being ponsored by the Booster Club Besides Marycrest and St. Ambrose, again thi year, a rewarding night is in to which most AHS graduates apply, store for everyone. ophomore , jun ther will be other schools which have I'll bet everyone's eyes were on Sr . iors, and eniors are invited to come, participated in College Night before . Mary Ambrosina, BVM, when she compare, and judge the college so Among these are: John Carroll Univer said, "If you'll pay attention, I'll go that they can make a good decision on sity, Cleveland, Ohio; Western Illinois through the board." a pecific college. -

85737NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. / A !?~ liD 1j ~ \ ~~~~~~~ , ERNME , 'l , --~ --~--- ---- ----------------- -------------------------:;~ .. ---"'----,-.---"-" ,-,--------~-- ..--------- Consumer's Resource Handbook PUblished by Virginia H. Knauer Special Assistant to the President and Director U.S. Office of Consumer Affairs Prepared by: 1 ;r.' .::;' Anna Gen~' BarneN C -\1 l'E3l 'e:'::i Dan Rumelt Anne Turner Chapman td) JF~ i;;J), Juanita Yates Roger Goldblatt g;tj 1~ i~ iA~H1.f€fJnt~fl.19N s " Evelyn Ar,pstrong Nellie lfegans [;::;, Elva Aw-e-' .. Cathy' Floyd Betty Casey Barbara Johnson Daisy B. Cherry Maggie Johnson Honest transactions in a free market between Marion Q. Ciaccio Frank Marvin buyers and sellers are at the core of individual, Christine Contee Constance Parham community, and national economic growth. Joe Dawson Howard Seltzer Bob Steeves In the final analysis, an effective and efficient I' system of commerce depends on an informed :,; and educated public. An excerpt from President Reagan's Proclama· tion of National Consumers Week, Ap~~jl 25- May 1, 1982. September 1982 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This docl.ornent has been reproduced exactly as recei~e? from the person or organization orlqinating it. Points of view or opInions stat~d in tt;>is document are tho'se of the authors and do not nec~ssanly represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this ~ed material has been \' granted by ~bl;c Domajn II.S. Office of Consumer Affairs Additional free single copies of the Consumer's Resource Handbook may be obtained by writing to Handbook, , to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Davenport Downtown Commercial Historic District other names/site number Name of Multiple Property Listing (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number Downtown Davenport 2nd St. to 5th St., Perry St. to Western Ave. not for publication city or town Davenport vicinity state Iowa county Scott zip code 52801 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide X local Applicable National Register Criteria: X A B X C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date State Historical Society of Iowa State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

1964 Study Week on the Apostolate

OFFICIAL PROGRAM TION SCHOOL J . vs WAHLERT· HIGH SCHOOL BER20 1963 Dubuque • LETTERMAN RETURNS • • • Almost exclusively an offensive player last In forecasting the coming season, Jim said, year, returning letterman Jim Rymars (42) is "Our backfield is real fast and looks good. slated to be one of the defensive mainstays Our spirit is real strong, and more than com in Assumption's football strategy this year. pensates for any lack of returning veterans. Our defense is also good." Jim looks forward 5'10", 176 lb. Rymars enjoys playing both to the games against West and Central to be offense and defense, and Coach Tom Sunder "real hard-fought contests." bruch has Jim starting tonight in the defensive fullback position. Says Coach Sunderbruch, In the opinions of coaches and team mem "We had Jim playing only offensive ball last bers, Rymars is the combination of a recep year. He developed rapidly, took our coaching tive, coachable, unassuming personality and an real well, and turned out to be a major exceptional football player. As the Times prospect for a defense regular." Democrat Pigskin Prevue said, Rymars is ex pected to "put some punch in the (Assump The coaches all agree that Jim is "a real tion) running attack from the fullback spot." aggressive, 'hard-nosed' kid." They also con Assumption fans are betting on it. cur on the fact that, "He's one of the team's best blockers and we're depending on him in our toughest defensive position." Another of Jim's as ets is his speed. Said Coach Sunderbruch, "Jim really surprised us. -

Default Rate, Percent of Borrowers in Default, and Number of Borrowers in Repayment

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 413 851 HE 030 763 TITLE FY 1995 Cohort Default Rates for Originating Lenders/Holders. INSTITUTION Office of Postsecondary Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1997-10-22 NOTE 238p. PUB TYPE Numerical/Quantitative Data (110) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Compliance (Legal); Educational Finance; *Eligibility; Federal Aid; Federal Programs; Higher Education; Legal Responsibility; *Loan Default; Loan Repayment; Postsecondary Education; Program Evaluation; Student Financial Aid; Student Loan Programs IDENTIFIERS National Student Loan Data System; Stafford Student Loan Program; Supplemental Loans for Students Program ABSTRACT This report provides data on fiscal year 1995 cohort default rates for lending institutions and loan holders with 30 or more borrowers in repayment, calculated from data reported to the National Student Loan Data System by guaranty agencies. Types of loans covered include subsidized Federal Stafford, unsubsidized Federal Stafford, Federal Supplemental Loans for Students (SLS), and Federal consolidation loans used to repay Stafford or SLS loans. Default rates are calculated for originating lenders and for current holders, by state, and in descending order of default rate. Also included is Office of Postsecondary Education identification number; lender name and address; default rate, percent of borrowers in default, and number of borrowers in repayment. (JLS) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best -

Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) 2016 on the Cover

Bi-State Region Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) 2016 On the Cover Top photo: Big River Resources ethanol facility, Galva, Illinois (Photo courtesy Patty Pearson) Bottom left photo: Lock and Dam 15 on the Mississippi River, Rock Island, Illinois Bottom middle photo: Genesis Medical Center expansion, Davenport, Iowa Bottom right photo: West 2nd Street, Muscatine, Iowa (Photo courtesy City of Muscatine) Executive Summary Executive Summary The Bi-State Region Economic Development District (also known CEDS was overviewed at the Bi-State Regional Commission meet- as the Bi-State Region) consists of Muscatine and Scott Counties ing, which is open to the public, on March 23, 2016, soliciting in Iowa and Henry, Mercer, and Rock Island Counties in Illinois. comments. The announcement of the draft being available for A map of the region can be found on page iii. The Economic public review was made at the meeting, and the draft was made Development Administration (EDA) designated the Bi-State available on the Bi-State Regional Commission website. Com- Region as an Economic Development District in 1980. The region ments on the plan have been minor, with small corrections to includes the Davenport-Moline-Rock Island, IA-IL Metropolitan projects in the Appendix (page 47). Statistical Area, which consists of Henry, Mercer, and Rock Island This CEDS document is made readily accessible to the economic de- Counties in Illinois and Scott County in Iowa. Muscatine County velopment stakeholders in the community. In creating the CEDS, in Iowa has been designated as a Micropolitan Statistical Area. there is a continuing program of communication and outreach that The main industries within the region are manufacturing, food encourages broad-based public engagement, participation, and manufacturing, agriculture, defense, logistics, and companies and commitment of partners. -

AGENDA I 35 S $ June 15, 2021

BAKER COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS 'W m. y in AGENDA I 35 s $ June 15, 2021 REGULAR SESSION 5:00 P.M. I. INVOCATION AND PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE II. APPROVAL OF AGENDA III. APPROVAL OF CONSENT AGENDA ITEMS 1. Minutes – June 1, 2021 – Regular Session 2. Minutes – June 1, 2021 - Public Hearing 3. Expense Report 4. Surplus Declaration; Robert Fletcher IV. PUBLIC COMMENTS V. CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS VI. NEW BUSINESS 1. Firewatch Council Presentation; Nick Howland Info Only 2. JAGC, Residual Meth Initiative; John Blanchard Action Item 3. E911 Grant Acceptance; John Blanchard Action Item 4. Medical Billing Hardships Assistance Guidelines; Chief Trevor Nelson Action Item 5. LPA Member Alternate to Voting Appointment; Lara Diettrich Action Item VII. PRIOR BUSINESS 1. Pending Business Report; Sara Little Info Only 2. Expense Report over $4500 Info Only 3. American Rescue Plan Update Info Only VIII. COUNTY MANAGER IX. COUNTY ATTORNEY X. COMMISSIONER COMMENTS If any member of the public desires to appeal a decision made at these hearings, he or she will need a record of the proceedings and for that purpose he or she may need to ensure that a verbatim record of the proceedings is transcribed, which record would include the testimony and evidence upon which the appeal is to be based. In accordance with the American with Disabilities Act, persons needing a special accommodation of an interpreter to participate in these proceedings should contact the County Commissioners Office at (904) 259-3613, at least 48 hours prior to the time of the hearing. Please Note: Items marked as “information only” or “for discussion” may have Board action taken at the time of discussion. -

2021 FEDERAL POVERTY GUIDELINES (FPG) ANNUAL & MONTHLY INCOME LEVELS from 100% to 250%

2021 FEDERAL POVERTY GUIDELINES (FPG) ANNUAL & MONTHLY INCOME LEVELS FROM 100% to 250% FAMILY FPG (100%) 125% of FPG 150% of FPG 175% of FPG 185% of FPG 200% of FPG 235% of FPG 250% of FPG SIZE YEAR MONTH YEAR MONTH YEAR MONTH YEAR MONTH YEAR MONTH YEAR MONTH YEAR MONTH YEAR MONTH 1 $12,880 $1,073 $16,100 $1,342 $19,320 $1,610 $22,540 $1,878 $23,828 $1,986 $25,760 $2,147 $30,268 $2,522 $32,200 $2,683 2 $17,420 $1,452 $21,775 $1,815 $26,130 $2,178 $30,485 $2,540 $32,227 $2,686 $34,840 $2,903 $40,937 $3,411 $43,550 $3,629 3 $21,960 $1,830 $27,450 $2,288 $32,940 $2,745 $38,430 $3,203 $40,626 $3,386 $43,920 $3,660 $51,606 $4,301 $54,900 $4,575 4 $26,500 $2,208 $33,125 $2,760 $39,750 $3,313 $46,375 $3,865 $49,025 $4,085 $53,000 $4,417 $62,275 $5,190 $66,250 $5,521 5 $31,040 $2,587 $38,800 $3,233 $46,560 $3,880 $54,320 $4,527 $57,424 $4,785 $62,080 $5,173 $72,944 $6,079 $77,600 $6,467 6 $35,580 $2,965 $44,475 $3,706 $53,370 $4,448 $62,265 $5,189 $65,823 $5,485 $71,160 $5,930 $83,613 $6,968 $88,950 $7,413 7 $40,120 $3,343 $50,150 $4,179 $60,180 $5,015 $70,210 $5,851 $74,222 $6,185 $80,240 $6,687 $94,282 $7,857 $100,300 $8,358 8 $44,660 $3,722 $55,825 $4,652 $66,990 $5,583 $78,155 $6,513 $82,621 $6,885 $89,320 $7,443 $104,951 $8,746 $111,650 $9,304 * $4,540 $378 $5,675 $473 $6,810 $568 $7,945 $662 $8,399 $700 $9,080 $757 $10,669 $889 $11,350 $946 *For family units over 8, add the amount shown for each additional member. -

Historic Preservation

Davenport 2025: Comprehensive Plan for the City Historic Preservation - 155 - Davenport 2025: Comprehensive Plan for the City Summary The historic preservation chapter (1986) of the city’s comprehensive plan asks the question, “What is ‘historic preservation?’” The answers provided by the authors are still true today: Put simply, historic preservation is the national movement to conserve the human-made environment. It includes efforts to protect buildings, structures, sites and neighborhoods associated with important people, events and developments. It is a movement which draws from the disciplines of history, architecture and archaeology and links us with our heritage.1 The 1986 chapter established five goals for Davenport’s historic preservation efforts: protect and enhance the character of the community’s significant neighborhoods and landmarks, coordinate local preservation efforts between the public and private sector, develop tools to create a favorable preservation climate, use preservation to strengthen the local economy, and increase the public awareness of the community’s history, culture, and heritage to create a sense of pride, place, and continuity.2 Davenport, like many communities across the country, experienced mixed preservation results over the past twenty years. The community has established numerous local and national historic districts in our community’s neighborhoods. State and local governments have cooperated to strengthen the city’s preservation programs in specific instances. The city has created incentives that can be used to preserve, protect, and enhance our built environment. On the downside, the city has failed to capitalize economically on its history, and the community has mixed feelings about the methods of and the reasons for historic preservation.