Paul Verhoeven's Sci-Fi Trilogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

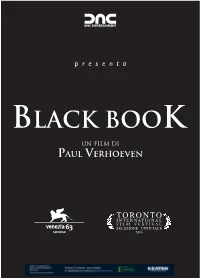

TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL SELEZIONE UFFICIALE 2006 Un Film Di PAUL VERHOEVEN UN KOLOSSAL BELLICO in CUI SUCCEDE DAVVERO OGNI COSA

presenta un film di PAUL VERHOEVEN TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL SELEZIONE UFFICIALE 2006 un film di PAUL VERHOEVEN UN KOLOSSAL BELLICO IN CUI SUCCEDE DAVVERO OGNI COSA. RITMO DA GRAN SPETTACOLO DI VITA E MORTE. (CORRIERE DELLA SERA) MOLTO SPETTACOLARE (LA STAMPA) GIRATO BENISSIMO, GRANDE RITMO, NON ANNOIA MAI (IL MESSAGGERO) IMMAGINI FORTI E DI GRANDE VALORE FIGURATIVO (IL TEMPO) TRADIZIONALE E INNOVATIVO. BELLO. (IL GIORNALE) VERHOEVEN AUTENTICA FORZA VISIONARIA (IL MANIFESTO) 10 MINUTI DI APPLAUSI AL FESTIVAL DI VENEZIA PREMIO ARCA CINEMAGIOVANI MIGLIOR FILM Dutch Film Festival PREMIO MIGLIOR FILM PREMIO MIGLIOR REGISTA PREMIO MIGLIORE ATTRICE Platinum Award MASSIMO CAMPIONE DI INCASSI IN OLANDA Oscar 2007 MIGLIOR FILM STRANIERO CANDIDATO UFFICIALE PER L’ OLANDA CAST ARTISTICO RachelSteinn/Ellis De Vries CARICE VAN HOUTEN Ludwig Müntze SEBASTIAN KOCH Hans Akkermans THOM HOFFMAN Ronnie HALINA REIJN Ufficiale Franken WALDEMAR KOBUS Gerben Kuipers DEREK DE LINT GeneraleSS Käutner CHRISTIAN BERKEL VanGein PETER BLOK Rob MICHIEL HUISMAN Tim Kuipers RONALD ARMBRUST voci italiane RachelSteinn/Ellis De Vries CHIARA COLIZZI Ludwig Müntze LUCA WARD Hans Akkermans MASSIMO LODOLO Ronnie LAURA BOCCANERA Ufficiale Franken MASSIMO CORVO Gerben Kuipers GINO LA MONICA dialoghi e direzione del doppiaggio MASSIMO CORVO stabilimento di doppiaggio TECHNICOLOR SOUND SERVICES CAST TECNICO regia: PAUL VERHOEVEN storia originale: GERARD SOETEMAN sceneggiatura: GERARD SOETEMAN direttore della fotografia: PAUL VERHOEVEN luci: KARLWALTER LINDENLAUB, ACS, -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven Limited Edition Blu-ray release (2-disc set) on 2 December 2019 From legendary filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Basic Instinct) and screenwriter Gerard Soeteman (Soldier of Orange) comes an explosive, fast-paced and thrilling coming- of-age drama. Raw, intense and unabashedly sexual, Spetters is a wild ride that will knock the unsuspecting for a loop. Starring Renée Soutendijk, Jeroen Krabbé (The Fugitive) and the late great Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner), this limited edition 2-disc set (1 x Blu-ray & 1 x DVD) brings Spetters to Blu-ray for the first time in the UK and is a must own release, packed with over 4 hours of bonus content. In Spetters, three friends long for better lives and see their love of motorcycle racing as a perfect way of doing it. However the arrival of the beautiful and ambitious Fientje threatens to come between them. Special features Remastered in 4K and presented in High Definition for the first time in the UK Audio commentary by director Paul Verhoeven Symbolic Power, Profit and Performance in Paul Verhoeven’s Spetters (2019, 17 mins): audiovisual essay written and narrated by Amy Simmons Andere Tijden: Spetters (2002, 29 mins): Dutch TV documentary on the making of Spetters, featuring the filmmakers, cast and critics of the film Speed Crazy: An Interview with Paul Verhoeven (2014, 8 mins) Writing Spetters: An Interview with Gerard Soeteman (2014, 11 mins) An Interview with Jost Vacano (2014, 67 mins): wide ranging interview with the film’s cinematographer discussing his work on films including Soldier of Orange and Robocop Image gallery Trailers Illustrated booklet (***first pressing only***) containing a new interview with Paul Verhoeven by the BFI’s Peter Stanley, essays by Gerard Soeteman, Rob van Scheers and Peter Verstraten, a contemporary review, notes on the extras and film credits Product details RRP: £22.99 / Cat. -

Imperialism and Exploration in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2016 Off The Road: Imperialism And Exploration in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College Recommended Citation Wright, Andy, "Off The Road: Imperialism And Exploration in the American Road Movie" (2016). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 75. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/75 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wright 1 OFF THE ROAD Imperialism And Exploration In The American Road Movie “Road movies are too cool to address serious socio-political issues. Instead, they express the fury and suffering at the extremities of a civilized life, and give their restless protagonists the false hope of a one-way ticket to nowhere.” –Michael Atkinson, quoted in “The Road Movie Book” (1). “‘Imperialism’ means the practice, the theory, and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory; ‘colonialism’, which is almost always a consequence of imperialism, is the implanting of settlements on distant territory” –Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (9) “I am still a little bit scared of flying, but I am definitely far more scared of all the disgusting trash in between places” -Cy Amundson, This Is Not Happening “This is gonna be exactly like Eurotrip, except it’s not gonna suck” -Kumar Patel, Harold and Kumar Escape From Guantanamo Bay Wright 2 Off The Road Abstract: This essay explores the imperialist nature of the American road movie as it is defined by the film’s era of release, specifically through the lens of how road movies abuse the lands that are travelled through. -

159 Minutes Directed & Produced by Robert Altman Written by Joan

APRIL 17, 2007 (XIV:13) (1975) 159 minutes Directed & produced by Robert Altman Written by Joan Tewkesbury Original music by Arlene Barnett, Jonnie Barnett, Karen Black, Ronee Blakley, Gary Busey, Keith Carradine, Juan Grizzle, Allan F.Nicholls, Dave Peel, Joe Raposo Cinematography by Paul Lohmann Film Editiors Dennis M. Hill and Sidney Levin Sound recorded by Chris McLaughlin Sound editor William A. Sawyer Original lyrics Robert Altman, Henry Gibson, Ben Raleigh, Richard Reicheg, Lily Tomlin Political campaign designer....Thomas HalPhillips David Arkin...Norman Barbara Baxley...Lady Pearl Ned Beatty...Delbert Reese Karen Black...Connie White Ronee Blakley...Barbara Jean Timothy Brown ...Tommy Brown Patti Bryant...Smokey Mountain Laurel Keith Carradine...Tom Frank Richard Baskin...Frog Geraldine Chaplin...Opal Jonnie Barnett...Himself Robert DoQui...Wade Cooley Vassar Clements...Himself Shelley Duvall...L. A. Joan Sue Barton...Herself Allen Garfield...Barnett Elliott Gould...Himself Henry Gibson...Haven Hamilton Julie Christie...Herself Scott Glenn...Private First Class Glenn Kelly Robert L. DeWeese Jr....Mr. Green Jeff Goldblum...Tricycle Man Gailard Sartain...Man at Lunch Counter Barbara Harris...Albuquerque Howard K. Smith...Himself David Hayward ...Kenny Fraiser Academy Award for Best Song: Keith Carradine, “I’m Easy” Michael Murphy...John Triplette Selected for the National Film Registry by the National Film Allan F. Nicholls...Bill Preservation Board Dave Peel...Bud Hamilton Cristina Raines...Mary ROBERT ALTMAN (20 February 1925, Kansas City, Bert Remsen...Star Missouri—20 November 2006, Los Angeles), has developed Lily Tomlin...Linnea Reese the form of interlocked narrative to a level that is frequently Gwen Welles ... Sueleen Gay copied (e.g. -

Accion Mutante

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Salford Institutional Repository “Esto no es un juego, es Acción mutante”: The Provocations of Álex de la Iglesia Peter Buse Núria Triana-Toribio Andrew Willis University of Salford University of Manchester University of Salford Speaking at the Manchester Spanish Film Festival in 2000, Álex de la Iglesia professed that he was not really a film director. “I’m more of a barman”, he claimed, “I just make cocktails”. His films, he implied, were simply an elaborate montage of quotations from other directors, genres, and film-styles, a self-assessment well borne out by Acción mutante (1993), the de la Iglesias team’s1 first feature film, which promiscuously mixes science fiction and comedy, film noir and western, Almodóvar and Ridley Scott. Were such a claim, and its associated renunciation of auteur status, to issue from an American independent director, or even a relatively self-conscious Hollywood director, would it even raise an eyebrow, so eloquently does it express postmodern orthodoxy? And does it make any difference when it comes from a modern Spanish director? As a bravura cut- and-paste job, a frenetic exercise in filmic intertextuality, Acción mutante is highly accomplished, but it would be a mistake to praise or criticize it on the grounds of its postmodern sensibilities alone without taking into account the intervention it made into a specifically Spanish filmic context where, in the words of the title song “Esto no es un juego, es acción mutante”. AFTER THE LEY MIRÓ Álex de la Iglesia has defined his cinema in terms of what it is not. -

Total Recall Actor Listäƒ (Cast)

Total Recall Actor Listă (Cast) Robert Picardo https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/robert-picardo-313789/movies Debbie Lee Carrington https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/debbie-lee-carrington-3020806/movies Robert Costanzo https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/robert-costanzo-1889355/movies Kamala Lopez https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/kamala-lopez-2445828/movies Arnold Schwarzenegger https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/arnold-schwarzenegger-2685/movies Marc Alaimo https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/marc-alaimo-926194/movies Roy Brocksmith https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/roy-brocksmith-3445751/movies Anne Lockhart https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/anne-lockhart-461742/movies Rosemary Dunsmore https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/rosemary-dunsmore-1614266/movies Priscilla Allen https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/priscilla-allen-3922146/movies Michael Ironside https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/michael-ironside-344973/movies Marshall Bell https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/marshall-bell-679987/movies Mickey Jones https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/mickey-jones-346965/movies Ronny Cox https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/ronny-cox-39989/movies Ray Baker https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/ray-baker-7297161/movies Dean Norris https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/dean-norris-432385/movies Rachel Ticotin https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/rachel-ticotin-262091/movies Mel Johnson, Jr. https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/mel-johnson%2C-jr.-3304853/movies Sharon Stone https://ro.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/sharon-stone-62975/movies. -

Will #Blacklivesmatter to Robocop?1

***PRELIMINARY DRAFT***3-28-16***DO NOT CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION**** Will #BlackLivesMatter to Robocop?1 Peter Asaro School of Media Studies, The New School Center for Information Technology Policy, Princeton University Center for Internet and Society, Stanford Law School Abstract Introduction #BlackLivesMatter is a Twitter hashtag and grassroots political movement that challenges the institutional structures surrounding the legitimacy of the application of state-sanction violence against people of color, and seeks just accountability from the individuals who exercise that violence. It has also challenged the institutional racism manifest in housing, schooling and the prison-industrial complex. It was started by the black activists Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, following the acquittal of the vigilante George Zimmerman in the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2013.2 The movement gained momentum following a series of highly publicized killings of blacks by police officers, many of which were captured on video from CCTV, police dashcams, and witness cellphones which later went viral on social media. #BlackLivesMatter has organized numerous marches, demonstrations, and direct actions of civil disobedience in response to the police killings of people of color.3 In many of these cases, particularly those captured on camera, the individuals who are killed by police do not appear to be acting in the ways described in official police reports, do not appear to be threatening or dangerous, and sometimes even appear to be cooperating with police or trying to follow police orders. While the #BlackLivesMatter movement aims to address a broad range of racial justice issues, it has been most successful at drawing attention to the disproportionate use of violent and lethal force by police against people of color.4 The sense of “disproportionate use” includes both the excessive 1In keeping with Betteridge’s law of headlines, one could simply answer “no.” But investigating why this is the case is still worthwhile. -

Michele Michel

MICHELE MICHEL Costume Designer FEATURES FOUR GOOD DAYS Rodrigo Garcia Indigenous Media Cast: Glenn Close, Mila Kunis Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival (2020) IS THAT A GUN IN YOUR POCKET…? Matt Cooper Pocketful Films, LLC. Cast: Andrea Anders, Matt Passmore, John Michael Higgins, Katherine McNamara THE LAST STAND Jee-woon Kim Lionsgate Cast: Arnold Schwarzenegger, Jaimie Alexander, Forest Whitaker, Peter Stormare STREET KINGS David Ayer Fox Searchlight Cast: Keanu Reeves, Chris Evans, Forest Whitaker, Hugh Laurie THE AIR I BREATHE Jieho Lee NALA Films, Paul Schiff P. Cast: Andy Garcia, Sarah Michelle Gellar, Kevin Bacon, Brendan Fraser, Forest Whitaker, Emile Hirsch HARSH TIMES David Ayer Crave Films Cast: Christian Bale Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2005) CONFIDENCE James Foley Lionsgate Films Cast: Dustin Hoffman, Ed Burns, Andy Garcia & Rachel Weisz TRAINING DAY Antoine Fuqua Warner Bros. Cast: Denzel Washington, Ethan Hawke Outlaw Productions I WITNESS Rowdy Harrington Promark Entertainment Group Cast: Jeff Daniels, James Spader, Portia de Rossi & Clifton Collins Jr. BREAD AND ROSES Ken Loach Parallax Pictures Cast: Pilar Padilla, Elpidia Carrillo, Adrien Brody Official Competitor, Cannes Film Festival (2000) SIMONE (Assistant Costume Designer) Andrew Nichol New Line Cinema Cast: Al Pacino, Winona Ryder, Catherine Keener THE INSIDER (Assistant Costume Designer) Michael Mann Touchstone Pictures Cast: Russell Crowe, Al Pacino TELEVISION THE ACT Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre Universal Cable Productions / Hulu Cast: -

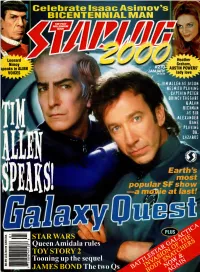

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

Starlog Magazine

Celebrate Isaac Asimov's BICENTENNIAL MAN 2 Leonard * V Heather Nimoy Graham, speaks in ALIEN — AUSTIN POWERS' VOICES lady love 1 40 (PIUS) £>v < -! STAR WARS CA J OO Queen Amidala rules o> O) CO TOY STORY 2 </) 3 O) Tooning up the sequel ft CD GO JAMES BOND The two Q THE TRUTH If you're a fantasy sci-fi fanatic, and if you're into toys, comics, collectibles, Manga and anime. if you love Star Wars, Star Trek, Buffy, Angel and the X-Files. Why aren't you here - WWW.ign.COtH mm INSIDE TOY STORY 2 The Pixarteam sends Buzz & Woody off on adventure GALAXY QUEST: THE FILM Questarians! That TV classic is finally a motion picture HEROES OF THE GALAXY Never surrender these pin- ups at the next Quest Con! METALLIC ATTRACTION Get to know Witlock, robot hero & Trouble Magnet ACCORDING TO TIM ALLEN He voices Buzz Lightyear & plays the Questarians' favorite commander THAT HEROIC GUY Brendan Fraser faces mum mies, monsters & monkeys QUEEN AMIDALA RULES Natalie Portman reigns against The Phantom Menace THE NEW JEDI ORDER Fantasist R.A. Salvatore chronicles the latest Star Wars MEMORABLE CHARACTER Now & Again, you've seen actor ! Cerrit Graham 76 THE SPY WHO SHAGS WELL Heather Graham updates readers STARLOC: The Science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., 475 Park Avenue South, New York, on her career moves NY 10016. STARLOG and The Science Fiction Universe are registered trademarks of Starlog Group Inc' (ISSN 0191-4626) (Canadian GST number: R-124704826) This is issue Number 270, January 2000.