DOCTORAL THESIS Primary Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Independent Study, the Future of Artists and Architecture? Screening Programme, Selected by Vanessa Scully 19 October 2019

Thamesmead Texas presents: An independent study, the future of artists and architecture? Screening programme, selected by Vanessa Scully 19 October 2019 Thamesmead Texas presents a selection of experimental and documentary films on social housing, gentrification and regeneration from the 1970’s – present day London. Selected by artist Vanessa Scully, as part of the series ‘Thamesmead Texas presents: An independent study, the future of artists and architecture? This screening event sits within a new installation entitled ‘Heavy View’ by British Artist Laura Yuile that developed out of Yuile’s consideration of technological and architectural obsolescence. TACO!, 30 Poplar Place, Thamesmead, London SE28 8BA. Saturday 19 October, 7-10pm. Part One: Meanwhile space in London*, shorts Katharine Meynell, Kissing (2014), 3:00 mins, digital video John Smith, Dungeness (1987) 3:35 mins, 16mm film William Raban, Cripps at Acme (1981), 5:35 mins, 16mm film Wendy Short, Overtime (2016), 10:09 mins, digital video Channel 4, Home Truths – Art and Soul (2014), 4:51 mins, digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v1 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v2 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v3 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video John Smith & Jocelyn Pook, Blight (1996), 16 mins, 16mm film Part Two: A history of social housing in London, feature Tom Cordell, Utopia London (2010), 82 mins, digital video and archive material Tessa Garland, Here East (2017), 5:42 mins, HD video Part One: into his thirties) a figure to add to the pantheon of profoundly subversive, wildly misbehaved, and Katharine Meynell, Kissing (2014) perhaps genuinely unhinged twentieth-century artists, alongside Jack Smith, Harry Smith, Kenneth “Made in response to a word drawn from a hat with Anger, Chris Burden, Joe Coleman, and others.” LUX 13 Critical Forum, I kissed the iconic Balfron Jared Rap-fogelVol. -

International Pathway Programmes 2019/20

International Pathway Programmes 2019/20 London’s Campus University roehampton.ac.uk/pathway University of Roehampton Contents Welcome 4 Why Roehampton? 6 Our campus 9 Studying at Roehampton 10 Campus map 12 Supporting you 14 Free London 18 London’s campus university 20 Living costs 22 Sport at Roehampton 24 Your Students’ Union 26 Accommodation 28 Arriving at Roehampton 30 Pre-Sessional English 32 The Pathway College is a partnership between the University of Roehampton and QA Higher International Foundation Education – a UK Higher Education provider. The pathway programmes are validated by the Programme 34 University of Roehampton and taught by QA Higher Education. The University of Roehampton and QA Higher Education are committed to being equal Progression options 36 opportunities education providers and will therefore make reasonable adjustments for disabled applicants and students. How to apply 40 The information given in this publication is accurate at the time of going to print in March 2019 Our location and contacts 42 and the University of Roehampton and QA Higher Education will use all reasonable efforts to deliver the programmes as described. The University and QA Higher Education reserve the right to withdraw or change the programmes or programme combinations included in this prospectus. These changes will only be made as a result of UK legal compliance, minimum student number requirements or for course validation reasons and applicants will be contacted by the University or QA Higher Education in the instance of these changes occurring. Please check the website for up-to-date information on our programmes: roehampton.ac.uk/pathway 2 3 roehampton.ac.uk/pathway University of Roehampton Welcome At Roehampton, we believe passionately in the benefits of a university education undertaken away from your home country. -

Buses from Roehampton and Queen Mary's University

Buses from Roehampton and Queen Mary’s Hospital East Acton Du Cane Road Old Brompton Road Brunel Road Hammersmith Hospital WEST 430 72 East Acton South Kensington EAST BROMPTON for the Museums White City West Brompton 170 ACTON for BBC TV Centre Victoria Shepherd's Bush Lillie Road Victoria Coach Station Hammersmith HAMMERSMITH Fulham Palace Road Fulham Cemetery 85 Chelsea 265 Royal Hospital Road Putney Bridge Castelnau River Thames River Thames Barnes 493 Red Lion Putney North Sheen St. Mary's Church Manor Circus Battersea Bridge Road Rocks Lane RICHMOND Lower Richmond Road Lower Richmond Road Festing Road The Embankment Richmond BARNES Lower Richmond Road Lower Richmond Road PUTNEY Commondale Ruvigny Gardens Putney High Street Sheen Road Upper Richmond Upper Richmond Queens Road Road West Road West Barnes Common Barnes for North Sheen Thornton Road Priests Bridge Roehampton lane Upper Upper Upper Richmond East Sheen Upper Richmond Upper Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Road Putney Lombard Road Bus Station Sheen Lane Road West Priory Lane Gipsy Lane Leisure Centre Arts Theatre Kings Road Barnes Rosslyn Park R.F.C. Upper Upper Richmond Road Richmond Road Dover House Woodborough Road Methodist Church Roehampton Lane Road Fairacres Gibbon Walk UÚ Putney Hill ÚX ELMSHAW RD HAWK ESBURY ROAD St. John’s Avenue GB Clapham Junction Digby Stuart HC College CLAPHAM The yellow tinted area includes every bus PARKSTEAD ROAD stop up to about one-and-a-half miles from Roehampton University Queen Mary’s JUNCTION Roehampton and Queen Mary's Hospital. HD Hospital GA AY Putney Hill Main stops are shown in the white area CRESTW Ú AY South Thames College outside. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019/20

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019/20 Roehampton University Company Registration Number 5161359 (England and Wales) Contents Chair of Council’s Welcome ..................................................................................... 4 Strategic Report ........................................................................................................... 6 Key Performance Indicators.................................................................................. 8 Financial Review ....................................................................................................10 Student Experience ...............................................................................................12 Staff Experience.....................................................................................................15 Learning, Teaching and Student Success ........................................................16 Research .................................................................................................................18 Outreach, Participation and Community Engagement .................................. 20 Responsible University .........................................................................................22 Risk and Uncertainty .............................................................................................24 Members of Council Report ...................................................................................26 Statement of Public Benefit.................................................................................28 -

Getting to Elm Grove Location

University of Roehampton London SW15 5PH Elm Grove Grove House Parkstead House GETTING TO ELM GROVE LOCATION MAP Elm Grove is situated on the main campus of the University of Roehampton, please enter through the main University gates off Roehampton Lane. Elm Grove and Welcome Centre reception is situated to the left as you enter through these gates or if you are wishing to park please turn right for the main car park. TRAVELLING BY PUBLIC TRANSPORT TRAVELLING BY CAR CENTRAL ELM GROVE LONDON BARNES National rail From central London BR STATION CHMOND ROAD AR) R RI (SOUTH CIRCUL A3 • Southwest Trains service from London Waterloo to Barnes. • A3 south from London A205 UPPE 0 6 HEATHROW AIRPORT • Southwest Trains service from Clapham Junction to Barnes. • Turn right on to Roehampton Lane A308 R ROEHAMPTON O • Please visit National Rail Enquiries for arrival and departure times. • Follow Roehampton Lane for one mile, after Clarence Lane on the CLUB EH AM left take the second left. After entering through the main gates, • Please note that Elm Grove is a 15 minute walk from Barnes train P T Elm Grove is situated slightly to the left. ROEHAMPTON O GROVE HOUSE station or if you prefer : PRIORY N L A • Take a bus by exiting the station and crossing over the bridge N E By car from the North BANK OF ENGLAND signposted towards Roehampton. The 265 bus stop is on the SPORTS CENTRE ROEHAMPTON E left hand side of the road. CLUB QUEENS N BUILDING LA • M1 south to junction 6A (M25 direction Heathrow) GOLF COURSE • Alight at Roehampton University Main Entrance bus stop; walk N O • M40 south to junction 1A (M25 direction Heathrow) CLARENC T up towards the traffic lights, cross over the road. -

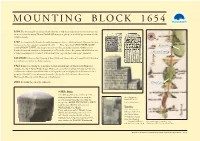

Roehampton Mounting Block Information Board

MOUNTING BLOCK 1654 1654: This mounting block and unofficial milestone, to help horse-riders dismount and remount, was set up at or near this site by Thomas Nuthall of Roehampton, perhaps to mark his appointment as local surveyor of roads. 1787: A passing traveller described it, with drawings, in a letter to The Gentleman’s Magazine (the first known record of it), signed anonymously J.L. of D____, Kent. Apart from MYLS THREE SCORE Richmond Park from LONDON TOWNE, the inscriptions, most now lost, are largely enigmatic. Ogilby had two London-Portsmouth distances: a ‘dimensuration’ of 73½ miles, close to the present official distance, and 9 miles from Cornhill a ‘vulgar computation’ of 60 miles. J.L. wrote that it was “opposite the 9-mile stone.” (see below) 1814/1821: Mentioned by Manning & Bray (1814) and Thomas Kitson Cromwell (1821) but then lost, perhaps removed for road improvements. 1921: Rediscovered during the demolition of a barn in Parish Yard, off Wandsworth High Street (opposite the end of Putney Bridge Road). How it came to be there is a mystery. It was identified by local historian and nurseryman Ernest Dixon, who purchased it and displayed it in his nurseries (later garage) on West Hill. It was subsequently moved to the garden of a local house, then stored at Wandsworth Museum and the University of Roehampton. 2018: Re-installed at or near its original site. Tibbet’s Corner 9-Mile Stone This damaged milestone, at the top of the nearby pedestrian subway, was set up by Above: Inscriptions an 18th century turnpike trust, with the drawn by J.L. -

8 Design and Planning Concepts That We Use. They Did Not Arrive Fully Formed at Our Pencil Tips and Com- Puter Keyboards! Some C

Walters_01.qxd 2/26/04 7:19 PM Page 8 DESIGN FIRST: DESIGN-BASED PLANNING FOR COMMUNITIES design and planning concepts that we use. They did not arrive fully formed at our pencil tips and com- puter keyboards! Some continue recent trends, or reclaim discarded or outdated concepts; others are deliberate reactions against perceived mistakes of the past. Our ideas come with a history, and we are guided in our practice by the knowledge of how they were derived and how they have been used (and mis- used) by professionals in previous times and places. But first we must be careful to define what consti- tutes our ‘history’. Historians and critics are often Figure 1.1 Alton West Estate, Roehampton, London, tempted to seek some overarching ‘grand narrative’ as London County Council Architects’ Department, a framework for their arguments (we are no different 1959. Bold versions of Le Corbusier’s Unité in this regard except that we are wary of the process d’Habitation are set in the soft landscape of south and its results!) and for much of the twentieth London, creating an image of the modernist dream. century the history, theory and practice of modern Compare this image with Figure 1.4. architecture was presented as a unified, coherent story by writers such as Hitchcock and Johnson the masters being interpreted by less talented pupils, (1932), Pevsner (1936), Richards (1940), and but increasing popular discontent, particularly Giedion (1941). In this tale of the ‘International against programs of urban reconstruction in Britain Style,’ the heroes were Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and urban renewal in America, gradually made the Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilbersheimer, modernist position untenable. -

Buses from Clapham Junction Buses from Richmond 49 Bus Night Buses N19 N31 N35 N87

Buses from Clapham Junction 87 Shoreditch South Kensington Aldwych SHOREDITCH Church 35 Ladbroke Grove for the Museums 319 for Covent Garden 77 Shoreditch Latimer Road Sainsbury's Sloane Square and London Transport Museum 24 hour Waterloo High Street Gloucester service 24 hour 345 Trafalgar Square for IMAX Cinema and 49 295 service Road St Ann's Road Royal Marsden Hospital Chelsea VICTORIA for Charing Cross South Bank Arts Complex Liverpool Street White City Old Town Hall 170 Shepherd's Kensington Chelsea Victoria County Hall 24 hour Bus Station 344 service Kensington High Street Palace Gate Beaufort Street for London Aquarium for Westfield Bush Westminster Olympia Kensington Parliament Square and London Eye for Westfield Beaufort Street Albert Bridge Monument King's Road Chelsea Embankment Victoria Earl's Court C3 St Thomas' WHITE KENSINGTON Tesco Coach Station Tate Britain Hospital Hammersmith CITY Earl's Court Southwark Bridge Charing Cross Hospital Bankside Pier for Globe Theatre Gunter Grove London Bridge Battersea Bridge for Guy's Hospital and the London Dungeon Fulham Cross King's Road River Thames Lambeth Borough Lots Road Battersea Battersea Palace Dawes Road Battersea Imperial Police Station BATTERSEA Dogs & Cats Elephant Wharf Vicarage Crescent Park Home Vauxhall Fulham Broadway Battersea High Street & Castle 24 hour Hail section& Ride 156 Peckham 37 service Battersea Battersea 24 hour Wandsworth Bridge Road Latchmere Park Road Road 345 service Sands End Peckham FULHAM Sainsbury's Wandsworth Walworth Road Lombard Road Queenstown -

Covid Vaccine: Communications and Engagement Activities to Build Confidence, Manage Expectations and Increase Uptake

Covid vaccine: Communications and engagement activities to build confidence, manage expectations and increase uptake Live document: due to fast moving operational programme Updated regularly in liaison with Wandsworth LA, NHS, Healthwatch and voluntary partners and the Communications and Engagement Team March 2021 1 This slide deck: • Objectives for communications and engagement • Where we are delivering vaccine/JCVI priority groups/How people are being contacted • Overview of comms and engagement • More detail on comms and engagement activities and approach with: – local communities – health and care staff – stakeholders and partners – social media, media and digital • Evaluation 2 Objectives for communications and engagement 1. Build confidence in the covid vaccine 2. Manage expectations about when local people will receive it 3. Increase uptake particularly in priority communities - by listening to, understanding local concerns and providing information in a factual and unbiased way 4. Support our NHS frontline with their operational communications around delivering the vaccine 3 Where we are delivering the vaccine Delivery model overview: defined centrally by NHS England to ensure consistency in deployment across all regions. Community vaccination centres Local vaccination centres Hospital & trust hubs High volumes, high throughput in a fixed • 7 GP led sites in Wandsworth: Delivered from NHS provider premises of location for an extended period e.g. sports • Balham Health Centre a defined number of hubs and further venues, conference -

Buses from St. George's Hospital

N44 Buses from St. George’s Hospital Victoria Street Victoria Coach Station Victoria 44 Westminster Trafalgar Square Aldwych for Charing Cross N155 River Thames 77 270 Chelsea Bridge Wandsworth Vauxhall Lambeth St. Thomas’ County Hall Waterloo Putney Palace Hospital for London Eye 155 for Imax Cinema and Bridge Battersea Road Southbank Centre Shaftesbury Estate Elephant & Castle G1 Hail & Ride Kennington Battersea section Park 219 Clapham Junction Broomwood Kennington Battersea Battersea Rise Road Oval Latchmere Hail & Ride Putney section St. Mary’s Church Northcote Road River Thames Battersea Salcott Road Stockwell High Street Clapham North Wandsworth Trinity Road for Clapham High Street 493 Town Clapham Common North Sheen Trinity Road Wandsworth Manor Circus Burntwood Lane Common CLAPHAM RICHMOND Clapham Wandsworth South Southside Shopping Centre Springfield University Richmond Hospital Trinity Road Earlsfield St. George’s Grove 57 Balham Sheen Road Manor Road Clapham Park P Atkins Road G for North Sheen E V A E R N - R D S A A O E R R HR T B E Y AT T W East Sheen R O Streatham Hill Sheen Lane Plough Lane A D HS Telford Avenue for Mortlake B L D Tooting Bec HJ OA A R HP L A C IN Route finder NTA N K FOU E S HB H HK HA Upper Tooting Road Day buses including 24 hour routes Barnes Common A Streatham Hill W HL C Roehampton Lane O Bus route Towards Bus stops V E R T HS O Tooting 44 Tooting R N Gap Road O St. George’s Broadway STREATHAM Victoria HR Queen Mary’s Hospital A Streatham D HC Hail & Ride Hospital R St. -

REGENERATION NEWS WINTER 2020 Issue 27

REGENERATION NEWS WINTER 2020 Issue 27 www.AltonEstateRegen.co.uk www.wandsworth.gov.uk/roehampton PLANNING APPLICATION UPDATE ST MARY’S HOSPITAL UPDATE WINTER UPDATE FROM ANDREW LOXTON WANDSWORTH ARTS FRINGE 2021 ALTON’S FIRST CHRISTMAS TREE HEY KIDS! Can you find the 7 festive bulls hidden in this newsletter? This newsletter is produced by Wandsworth Council to help keep you informed about the regeneration of your estate CHRISTMAS IN ROEHAMPTON BY ANDREW LOXTON Although Covid-19 has meant that many of the a vibrant carnival dance guaranteed to bring traditional events and activities for older people sunshine and smiles even on the gloomiest days. in Roehampton will not be able to take place this To book your own personal performance contact Christmas, there are still many activities planned to [email protected]. help mark the festive occasion: SUGAR SMART are looking for older residents to share REGENERATE RISE will be providing Christmas bags their favourite cake, biscuit and sweet recipes in order and a Santa’s sleigh with music from Songs on Wheels to create healthier versions that will be then given free across Roehampton and Putney, distributing mince of charge to older people in Roehampton. For more pies and some much-needed Christmas cheer. For information please contact [email protected]. more information please contact Mo Smith on 07774 116972 or email [email protected]. BAGS OF TASTE are providing recipes AGE UK WANDSWORTH can provide support with your and material for food shopping through their independent shopper healthy and tasty service. They will set up your online shopping account meals and will deliver with your favourite shop, do the first few shops for the ingredients and you and then support you to do it yourself. -

London's Next Huge Growth Opportunity

Zones Two and Three LONDON’S NEXT HUGE GROWTH OPPORTUNITY Exploring the potential for economic growth and regeneration in Zones Two and Three February 2016 Exploring the potential for economic growth and regeneration in Zones Two and Three The Premise Central London will continue to be the strongest economic hub in the UK, if not Europe Population, jobs, infrastructure and regeneration will drive growth in Zones 2 and 3 The following is a snapshot of a range of factors and indicators that illustrate the power of these trends Exploring the potential for economic growth and regeneration in Zones Two and Three Themes 1) London’s Growth is changing its Shape 2) The Centre is Booming but Expensive 3) Zones 2 and 3 are Growing 4) Strategic Infrastructure Benefits More than the Core 5) Delivered and Emerging Infrastructure Steers Growth 6) Investors are seeking new Opportunities 7) Local Authorities are Positioning Major Schemes 8) London Government is Aligned and Investing Exploring the potential for economic growth and regeneration in Zones Two and Three A Reminder: TfL Zones and Boroughs Central/Zone 1 Kensington and Chelsea, Westminster, City of London Zone 6 Inner / Zone 2 Zone 5 Camden, Zone 4 Hackney, Zone 3 Hammersmith Zone 2 and Fulham, Zone 1 Islington, Lambeth, Lewisham, Newham, Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Wandsworth Inner / Zone 3 Brent, Ealing, Greenwich, Haringey, Havering, Newham, Richmond upon Source: Google Maps Thames, Waltham Forest Exploring the potential for economic growth and regeneration in Zones Two and Three Higher Growth