8 Design and Planning Concepts That We Use. They Did Not Arrive Fully Formed at Our Pencil Tips and Com- Puter Keyboards! Some C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen' S Wood

Queen’s Wood , formerly Noel Park Estate , Tower Gardens Tottenham Cemetery known as Churchyard historic 19th Century Estate , council was opened in 1857 with Bottom Wood, was affordable housing estate built 100 years various later extensions. It purchased by Hornsey development, now a ago as a ‘garden is a conservation area with Urban District Council conservation area. suburb’ – now a listed features such as the d WH a ITE H conservation area. o ART L two chapels. in 1898. It is an Noel Park North Area R ANE t Crei t ghton a Road Residents Association: Tower Gardens y ancient woodland r WH F 10 TOTTENHAM CEMETERY ITE HA Residents Group : Allotments RT LANE and a designated www.noelparknorth. The Roundw ay rst Rd local nature reserve. wordpress.com www.towergardensn17. Penshu Moselle St t Friends of Queen’s Wood: org.uk Whitehall S d Pax d ton Road R R 11 M e TOTTENHAM r www.fqw.org.uk y a y e r o Bruce Castle is a Grade 1 a sh f m NE w a CEMETERY u d x HIP LA ll a S n e D e R T R l LO u h listed 16th century manor o B C F hur o e a 9 ch Roa Tower Gardens Estate 8 d R R d ou D 6 e n 12 A house. It opened as a WOOD GREEN h d S T w O a R a l y i UE s H museum in 1906. Bruce N b AVE G u d I E V L r R H r M EL i OS n y BRUCE CASTLE e Castle Park was the first n a M e c v y R o e n i e t W n o a R s G g d a R la t LO L PARK & MUSEUM e R n R d d D i public park in Tottenham. -

An Independent Study, the Future of Artists and Architecture? Screening Programme, Selected by Vanessa Scully 19 October 2019

Thamesmead Texas presents: An independent study, the future of artists and architecture? Screening programme, selected by Vanessa Scully 19 October 2019 Thamesmead Texas presents a selection of experimental and documentary films on social housing, gentrification and regeneration from the 1970’s – present day London. Selected by artist Vanessa Scully, as part of the series ‘Thamesmead Texas presents: An independent study, the future of artists and architecture? This screening event sits within a new installation entitled ‘Heavy View’ by British Artist Laura Yuile that developed out of Yuile’s consideration of technological and architectural obsolescence. TACO!, 30 Poplar Place, Thamesmead, London SE28 8BA. Saturday 19 October, 7-10pm. Part One: Meanwhile space in London*, shorts Katharine Meynell, Kissing (2014), 3:00 mins, digital video John Smith, Dungeness (1987) 3:35 mins, 16mm film William Raban, Cripps at Acme (1981), 5:35 mins, 16mm film Wendy Short, Overtime (2016), 10:09 mins, digital video Channel 4, Home Truths – Art and Soul (2014), 4:51 mins, digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v1 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v2 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v3 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video John Smith & Jocelyn Pook, Blight (1996), 16 mins, 16mm film Part Two: A history of social housing in London, feature Tom Cordell, Utopia London (2010), 82 mins, digital video and archive material Tessa Garland, Here East (2017), 5:42 mins, HD video Part One: into his thirties) a figure to add to the pantheon of profoundly subversive, wildly misbehaved, and Katharine Meynell, Kissing (2014) perhaps genuinely unhinged twentieth-century artists, alongside Jack Smith, Harry Smith, Kenneth “Made in response to a word drawn from a hat with Anger, Chris Burden, Joe Coleman, and others.” LUX 13 Critical Forum, I kissed the iconic Balfron Jared Rap-fogelVol. -

Haringey Story Map V4

Haringey: The Place London – Stansted North Middlesex Growth Corridor Hospital in Enfield For the third year running, our High Road West North Circular Tottenham University top performing school is St estate: the site of Technical College for Thomas More Catholic School our first large estate 14-19 year olds opened in Wood Green Enfield renewal in September 2014, sponsored by Spurs and A105 Middlesex University The most significant crime Bowes Park hotspot is in the Wood Bounds Northumberland Coldfall Wood, one of our Green/Turnpike Lane Green Park is the most White Hart Lane 18 Green Flag parks and corridor deprived ward in open spaces London Tottenham Northumberland A10 Bruce Castle Hotspur Park A Grade I 16th century Museum Football Club manor is home to Civic Centre Bruce Castle museum Wood Green Lee Valley Fortismere School in Muswell Alexandra Palace Regional Park N17 Design Studio Hill featured as one of the Top with John McAslan + 20 comprehensives in the Partners, offering country in The Times Wood Green / Bruce Grove work placements and Potential Crossrail 2 stations at Haringey Heartlands training to local Alexandra Palace and Turnpike regeneration area people Lane, as well as at Seven Broadwater Farm Sisters, Tottenham Hale and Estate Life expectancy gap: Men Northumberland Park Turnpike Lane Tottenham Green Waltham Forest in Crouch End- 82.6 years; in Northumberland College of Muswell Hill Haringey, Enfield 30 minutes Park-76 years Tottenham A504 and North East Tottenham Hale - Hornsey London Hale Stansted Airport Barnet Seven -

International Pathway Programmes 2019/20

International Pathway Programmes 2019/20 London’s Campus University roehampton.ac.uk/pathway University of Roehampton Contents Welcome 4 Why Roehampton? 6 Our campus 9 Studying at Roehampton 10 Campus map 12 Supporting you 14 Free London 18 London’s campus university 20 Living costs 22 Sport at Roehampton 24 Your Students’ Union 26 Accommodation 28 Arriving at Roehampton 30 Pre-Sessional English 32 The Pathway College is a partnership between the University of Roehampton and QA Higher International Foundation Education – a UK Higher Education provider. The pathway programmes are validated by the Programme 34 University of Roehampton and taught by QA Higher Education. The University of Roehampton and QA Higher Education are committed to being equal Progression options 36 opportunities education providers and will therefore make reasonable adjustments for disabled applicants and students. How to apply 40 The information given in this publication is accurate at the time of going to print in March 2019 Our location and contacts 42 and the University of Roehampton and QA Higher Education will use all reasonable efforts to deliver the programmes as described. The University and QA Higher Education reserve the right to withdraw or change the programmes or programme combinations included in this prospectus. These changes will only be made as a result of UK legal compliance, minimum student number requirements or for course validation reasons and applicants will be contacted by the University or QA Higher Education in the instance of these changes occurring. Please check the website for up-to-date information on our programmes: roehampton.ac.uk/pathway 2 3 roehampton.ac.uk/pathway University of Roehampton Welcome At Roehampton, we believe passionately in the benefits of a university education undertaken away from your home country. -

Buses from Roehampton and Queen Mary's University

Buses from Roehampton and Queen Mary’s Hospital East Acton Du Cane Road Old Brompton Road Brunel Road Hammersmith Hospital WEST 430 72 East Acton South Kensington EAST BROMPTON for the Museums White City West Brompton 170 ACTON for BBC TV Centre Victoria Shepherd's Bush Lillie Road Victoria Coach Station Hammersmith HAMMERSMITH Fulham Palace Road Fulham Cemetery 85 Chelsea 265 Royal Hospital Road Putney Bridge Castelnau River Thames River Thames Barnes 493 Red Lion Putney North Sheen St. Mary's Church Manor Circus Battersea Bridge Road Rocks Lane RICHMOND Lower Richmond Road Lower Richmond Road Festing Road The Embankment Richmond BARNES Lower Richmond Road Lower Richmond Road PUTNEY Commondale Ruvigny Gardens Putney High Street Sheen Road Upper Richmond Upper Richmond Queens Road Road West Road West Barnes Common Barnes for North Sheen Thornton Road Priests Bridge Roehampton lane Upper Upper Upper Richmond East Sheen Upper Richmond Upper Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Road Putney Lombard Road Bus Station Sheen Lane Road West Priory Lane Gipsy Lane Leisure Centre Arts Theatre Kings Road Barnes Rosslyn Park R.F.C. Upper Upper Richmond Road Richmond Road Dover House Woodborough Road Methodist Church Roehampton Lane Road Fairacres Gibbon Walk UÚ Putney Hill ÚX ELMSHAW RD HAWK ESBURY ROAD St. John’s Avenue GB Clapham Junction Digby Stuart HC College CLAPHAM The yellow tinted area includes every bus PARKSTEAD ROAD stop up to about one-and-a-half miles from Roehampton University Queen Mary’s JUNCTION Roehampton and Queen Mary's Hospital. HD Hospital GA AY Putney Hill Main stops are shown in the white area CRESTW Ú AY South Thames College outside. -

Food Businesses in Haringey That Have Been Awarded the Healthier Catering Commitment Award

Food businesses in Haringey that have been awarded the Healthier Catering Commitment Award: Name Address 3 Points Cafe 804 High Road, Tottenham, London. N17 0DH Alexandra Palace Ice Rink Alexandra Palace, Alexandra Palace Way, Wood Green, London. N22 7AY Angels Cafe 40 Stroud Green Road, Hornsey, London. N4 3ES Banana African Restaurant 594B High Road, Tottenham, London. N17 9TA and Bar Bardhoshi Bar & Restaurant 651 Green Lanes, Hornsey, London. N8 0QY Bickels Yard Food & Drink Tottenham Green Leisure Centre, 1 Philip Lane, Tottenham, London. N15 4JA Company @ Black Tap Coffee 2 Gladstone House, High Road, Wood Green, London. N22 6JS Blooming Scent Cafe Bernie Grant Performing Arts Centre, Town Hall Approach Road, Tottenham, London. N15 4RY Bodrum Café 6 Vicarage Parade, West Green Road, Tottenham, London. N15 3BL Brown Eagle 741 High Road, Tottenham, London. N17 8AG Food businesses in Haringey that have been awarded the Healthier Catering Commitment Award: Cafe 639 639 High Road, Tottenham, London. N17 8AA Cafe Lemon 118 West Green Road, Tottenham, London. N15 5AA Cafe N15 101 Broad Lane, Tottenham, London. N15 4DW Cafe Seven 497 Seven Sisters Road, Tottenham, London. N15 6EP Can Ciger Cigkofte 773 High Road, Tottenham, London. N17 8AH Candir 272 High Road, Tottenham, London. N15 4AJ Capital Restaurant 1-2 The Broadway, Wood Green, London. N22 6DS Charlie's Cafe & Bakery Ltd Unit 63B - Wood Green Shopping City, High Road, Wood Green, London. N22 6YD Chef Delight 13 High Road, Wood Green, London. N22 6BH Chesterways Unit 1- 252 High Road, Tottenham, London. N15 4AJ Chick King 755 High Road, Tottenham, London. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019/20

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019/20 Roehampton University Company Registration Number 5161359 (England and Wales) Contents Chair of Council’s Welcome ..................................................................................... 4 Strategic Report ........................................................................................................... 6 Key Performance Indicators.................................................................................. 8 Financial Review ....................................................................................................10 Student Experience ...............................................................................................12 Staff Experience.....................................................................................................15 Learning, Teaching and Student Success ........................................................16 Research .................................................................................................................18 Outreach, Participation and Community Engagement .................................. 20 Responsible University .........................................................................................22 Risk and Uncertainty .............................................................................................24 Members of Council Report ...................................................................................26 Statement of Public Benefit.................................................................................28 -

Getting to Elm Grove Location

University of Roehampton London SW15 5PH Elm Grove Grove House Parkstead House GETTING TO ELM GROVE LOCATION MAP Elm Grove is situated on the main campus of the University of Roehampton, please enter through the main University gates off Roehampton Lane. Elm Grove and Welcome Centre reception is situated to the left as you enter through these gates or if you are wishing to park please turn right for the main car park. TRAVELLING BY PUBLIC TRANSPORT TRAVELLING BY CAR CENTRAL ELM GROVE LONDON BARNES National rail From central London BR STATION CHMOND ROAD AR) R RI (SOUTH CIRCUL A3 • Southwest Trains service from London Waterloo to Barnes. • A3 south from London A205 UPPE 0 6 HEATHROW AIRPORT • Southwest Trains service from Clapham Junction to Barnes. • Turn right on to Roehampton Lane A308 R ROEHAMPTON O • Please visit National Rail Enquiries for arrival and departure times. • Follow Roehampton Lane for one mile, after Clarence Lane on the CLUB EH AM left take the second left. After entering through the main gates, • Please note that Elm Grove is a 15 minute walk from Barnes train P T Elm Grove is situated slightly to the left. ROEHAMPTON O GROVE HOUSE station or if you prefer : PRIORY N L A • Take a bus by exiting the station and crossing over the bridge N E By car from the North BANK OF ENGLAND signposted towards Roehampton. The 265 bus stop is on the SPORTS CENTRE ROEHAMPTON E left hand side of the road. CLUB QUEENS N BUILDING LA • M1 south to junction 6A (M25 direction Heathrow) GOLF COURSE • Alight at Roehampton University Main Entrance bus stop; walk N O • M40 south to junction 1A (M25 direction Heathrow) CLARENC T up towards the traffic lights, cross over the road. -

Broadwater Farmnewsletter

Autumn 2019 - Issue 2 Broadwater FarmNewsletter Growing is great on the Estate! Last year the Broadwater Farm Growing Project was awarded funding through the Community Voting day. Since then lots has been sowing, planting from happening to get families cuttings and growing in growing on the estate. your home. The aim of the project is to If you are interested in deliver workshops for the learning more about community so residents growing your own food can grow their own food. and want to get involved in the Broadwater Farm Workshops began in Growing Project, please February in Harmony contact Paulette on Gardens and residents built 07538 717885. planters and learnt about Keeping it clean and tidy! - see page 3 Paulette Henry and Joan Curtis in Harmony Gardens Meet the team and have your say Come and meet the Director and the BWF Team at the Broadwater Farm Community Centre. Free refreshments will be provided. • Wednesday 13th November between 2pm-5pm 1 Hy HfH Broadwater Farm Newsletter JUL 2019 No2.indd 1 29/10/2019 17:22 Broadwater Farm Newsletter - Autmun 2019 Upgrading kitchens and bathrooms 260 residents are benefitting from upgraded kitchen and bathroom works taking place across the estate. We spoke to Grace, Caroline Ali and Naomi resident from the Isaac are two qualified Broadwater farm Estate Occupational Therapists, about her experience, this who work in Haringey. is what she had to say. Once residents have been referred to them, they “The resident liaison officer complete a full assessment visited me to go over the to identify if any work that was going to take adaptations are needed. -

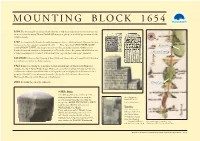

Roehampton Mounting Block Information Board

MOUNTING BLOCK 1654 1654: This mounting block and unofficial milestone, to help horse-riders dismount and remount, was set up at or near this site by Thomas Nuthall of Roehampton, perhaps to mark his appointment as local surveyor of roads. 1787: A passing traveller described it, with drawings, in a letter to The Gentleman’s Magazine (the first known record of it), signed anonymously J.L. of D____, Kent. Apart from MYLS THREE SCORE Richmond Park from LONDON TOWNE, the inscriptions, most now lost, are largely enigmatic. Ogilby had two London-Portsmouth distances: a ‘dimensuration’ of 73½ miles, close to the present official distance, and 9 miles from Cornhill a ‘vulgar computation’ of 60 miles. J.L. wrote that it was “opposite the 9-mile stone.” (see below) 1814/1821: Mentioned by Manning & Bray (1814) and Thomas Kitson Cromwell (1821) but then lost, perhaps removed for road improvements. 1921: Rediscovered during the demolition of a barn in Parish Yard, off Wandsworth High Street (opposite the end of Putney Bridge Road). How it came to be there is a mystery. It was identified by local historian and nurseryman Ernest Dixon, who purchased it and displayed it in his nurseries (later garage) on West Hill. It was subsequently moved to the garden of a local house, then stored at Wandsworth Museum and the University of Roehampton. 2018: Re-installed at or near its original site. Tibbet’s Corner 9-Mile Stone This damaged milestone, at the top of the nearby pedestrian subway, was set up by Above: Inscriptions an 18th century turnpike trust, with the drawn by J.L. -

Buses from Seven Sisters

WOOD GREEN HOLLOWAY STOKE NEWINGTON Buses from Seven Sisters Euston 279 Key Waltham Cross Bus Station —O Connections with London Underground W4 318 Turkey Street o Connections with London Overground Oakthorpe Park North Middlesex Hospital 349 R Connections with National Rail Ponders End Hail & Ride section Bus Garage D Connections with Docklands Light Railway Bull Lane Tottenhall Road Ponders End B Connections with river boats CITY OF High Street 24 hour 149 service 259 Tottenham Cemetery Edmonton Green LONDON White Hart Lane Bus Station Wolves Lane Upper Edmonton Hail & Ride section White Hart Lane Angel Corner for Silver Street Great Cambridge Road High Road Brantwood Road High Road The Roundway 476 White Hart Lane Waltheof Gardens The Roundway White Hart Lane Northumberland Awlfield Avenue Park Route finder 24 hour Shelbourne 243 service White Hart Lane Road WOOD Wood Green Hail & RideThe section Roundway All Hallows Road Tottenham Hotspur Football Club Day buses including 24-hour services Lansdowne Road Lordship Lane Lordship Lane High Road Lordship Lane Lordship Lane Tottenham Sports Centre Chalgrove Road Bus route Towards Bus stops GREEN The Roundway Enfield and Haringey Lansdowne Road Lordship Lane The Roundway Lordship Lane (East Arm) Magistrates Court Pembury Road Morley Avenue (West Arm) Awlfield Avenue Spencer Road 41 Archway +EL+M Wood Green Lansdowne Road Rosebery Avenue Tottenham Hale Shopping City Lordship Lane Lordship Lane Lordship Lane Lordship Lane High Road Tottenham High Road +FNQ Hornsey Perth Road Gladstone Waltheof -

Buses from Clapham Junction Buses from Richmond 49 Bus Night Buses N19 N31 N35 N87

Buses from Clapham Junction 87 Shoreditch South Kensington Aldwych SHOREDITCH Church 35 Ladbroke Grove for the Museums 319 for Covent Garden 77 Shoreditch Latimer Road Sainsbury's Sloane Square and London Transport Museum 24 hour Waterloo High Street Gloucester service 24 hour 345 Trafalgar Square for IMAX Cinema and 49 295 service Road St Ann's Road Royal Marsden Hospital Chelsea VICTORIA for Charing Cross South Bank Arts Complex Liverpool Street White City Old Town Hall 170 Shepherd's Kensington Chelsea Victoria County Hall 24 hour Bus Station 344 service Kensington High Street Palace Gate Beaufort Street for London Aquarium for Westfield Bush Westminster Olympia Kensington Parliament Square and London Eye for Westfield Beaufort Street Albert Bridge Monument King's Road Chelsea Embankment Victoria Earl's Court C3 St Thomas' WHITE KENSINGTON Tesco Coach Station Tate Britain Hospital Hammersmith CITY Earl's Court Southwark Bridge Charing Cross Hospital Bankside Pier for Globe Theatre Gunter Grove London Bridge Battersea Bridge for Guy's Hospital and the London Dungeon Fulham Cross King's Road River Thames Lambeth Borough Lots Road Battersea Battersea Palace Dawes Road Battersea Imperial Police Station BATTERSEA Dogs & Cats Elephant Wharf Vicarage Crescent Park Home Vauxhall Fulham Broadway Battersea High Street & Castle 24 hour Hail section& Ride 156 Peckham 37 service Battersea Battersea 24 hour Wandsworth Bridge Road Latchmere Park Road Road 345 service Sands End Peckham FULHAM Sainsbury's Wandsworth Walworth Road Lombard Road Queenstown