Linguistic Manifestations in the Commercialisation of Japanese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copy of Anime Licensing Information

Title Owner Rating Length ANN .hack//G.U. Trilogy Bandai 13UP Movie 7.58655 .hack//Legend of the Twilight Bandai 13UP 12 ep. 6.43177 .hack//ROOTS Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.60439 .hack//SIGN Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.9994 0091 Funimation TVMA 10 Tokyo Warriors MediaBlasters 13UP 6 ep. 5.03647 2009 Lost Memories ADV R 2009 Lost Memories/Yesterday ADV R 3 x 3 Eyes Geneon 16UP 801 TTS Airbats ADV 15UP A Tree of Palme ADV TV14 Movie 6.72217 Abarashi Family ADV MA AD Police (TV) ADV 15UP AD Police Files Animeigo 17UP Adventures of the MiniGoddess Geneon 13UP 48 ep/7min each 6.48196 Afro Samurai Funimation TVMA Afro Samurai: Resurrection Funimation TVMA Agent Aika Central Park Media 16UP Ah! My Buddha MediaBlasters 13UP 13 ep. 6.28279 Ah! My Goddess Geneon 13UP 5 ep. 7.52072 Ah! My Goddess MediaBlasters 13UP 26 ep. 7.58773 Ah! My Goddess 2: Flights of Fancy Funimation TVPG 24 ep. 7.76708 Ai Yori Aoshi Geneon 13UP 24 ep. 7.25091 Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Geneon 13UP 13 ep. 7.14424 Aika R16 Virgin Mission Bandai 16UP Air Funimation 14UP Movie 7.4069 Air Funimation TV14 13 ep. 7.99849 Air Gear Funimation TVMA Akira Geneon R Alien Nine Central Park Media 13UP 4 ep. 6.85277 All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Dash! ADV 15UP All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku TV ADV 12UP 14 ep. 6.23837 Amon Saga Manga Video NA Angel Links Bandai 13UP 13 ep. 5.91024 Angel Sanctuary Central Park Media 16UP Angel Tales Bandai 13UP 14 ep. -

Kawaguchi's ZIPANG, an Alternate Second World

Quaderns de Filologia. Estudis literaris. Vol. XIV (2009) 61-71 KAWAGUCHi’s Zipang, AN ALTERNATE SECOND WORLD WAR Pascal Lefèvre Hogeschool Sint-Lukas Brussel / Sint-Lukas Brussels University College of Art and Design Science-fiction is not necessarely about the future but it can deal with history as well. Since the publication of H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1895) time travel has become a popular feature of various SF-stories. Time travel has proven not only a fantastic device for imagining “what if” – stories, but also an intriguing means to revise past events from a contemporary perspective. A very interesting and recent example is Kaiji Kawaguchi’s ongoing manga series Zipangu (translated as Zipang in English and French), which has met since its start in 2001, in the popular Kodansha manga magazine Weekly Morning, both popular and critical success1 (Masanao, 2004: 184-187). By August 2008 some 400 episodes were collected in 36 volumes2 of the Japanese edition, and 21 volumes were translated into French3 – which will be the ones analysed in this article (the number of the volume will appear in Latin numbers, and the number of the episode in arabic numbers: followed by page number after a colon). While the English translation was suspended4, the French edition seems a lot more succesful, at least from a critical point of view – see Bastide (2006, 218-219) or Finet (2008: 272-273), and a nomination at the Angoulême comics festival in 2007). Zipang is not only a fairly skillfully manga for young males (“seinen”), but it adresses also a number of current political debates of Japan’s recent history and near future. -

Full Arcade List OVER 2700 ARCADE CLASSICS 1

Full Arcade List OVER 2700 ARCADE CLASSICS 1. 005 54. Air Inferno 111. Arm Wrestling 2. 1 on 1 Government 55. Air Rescue 112. Armed Formation 3. 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles 56. Airwolf 113. Armed Police Batrider Rally 57. Ajax 114. Armor Attack 4. 10-Yard Fight 58. Aladdin 115. Armored Car 5. 18 Holes Pro Golf 59. Alcon/SlaP Fight 116. Armored Warriors 6. 1941: Counter Attack 60. Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars 117. Art of Fighting / Ryuuko no 7. 1942 61. Ali Baba and 40 Thieves Ken 8. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen 62. Alien Arena 118. Art of Fighting 2 / Ryuuko no 9. 1943: The Battle of Midway 63. Alien Challenge Ken 2 10. 1944: The LooP Master 64. Alien Crush 119. Art of Fighting 3 - The Path of 11. 1945k III 65. Alien Invaders the Warrior / Art of Fighting - 12. 19XX: The War Against Destiny 66. Alien Sector Ryuuko no Ken Gaiden 13. 2 On 2 OPen Ice Challenge 67. Alien Storm 120. Ashura Blaster 14. 2020 SuPer Baseball 68. Alien Syndrome 121. ASO - Armored Scrum Object 15. 280-ZZZAP 69. Alien vs. Predator 122. Assault 16. 3 Count Bout / Fire SuPlex 70. Alien3: The Gun 123. Asterix 17. 30 Test 71. Aliens 124. Asteroids 18. 3-D Bowling 72. All American Football 125. Asteroids Deluxe 19. 4 En Raya 73. Alley Master 126. Astra SuPerStars 20. 4 Fun in 1 74. Alligator Hunt 127. Astro Blaster 21. 4-D Warriors 75. AlPha Fighter / Head On 128. Astro Chase 22. 64th. Street - A Detective Story 76. -

Myths of Hakkō Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender

Myths of Hakko Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender in Official Ceremonies of Modern Japan Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Teshima, Taeko Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 21:55:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194943 MYTHS OF HAKKŌ ICHIU: NATIONALISM, LIMINALITY, AND GENDER IN OFFICIAL CEREMONIES OF MODERN JAPAN by Taeko Teshima ______________________ Copyright © Taeko Teshima 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE CULTURAL AND LITERARY STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 6 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Taeko Teshima entitled Myths of Hakkō Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender in Official Ceremonies of Modern Japan and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Barbara A. Babcock _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Philip Gabriel _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Susan Hardy Aiken Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

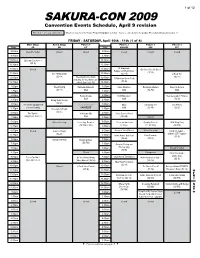

Sakura-Con 2009

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2009 FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 10th - 11th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 10th - 11th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 10th - 11th (4 of 4) Convention Events Schedule, April 9 revision Panels 5 Fan Workshop 1 Fan Workshop 2 Autographs Console Gaming Music Gaming Anime Theater 1 Anime Theater 2 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Classic Anime Theater Live-Action Theater Fansub Theater Karaoke Collectible Card Miniatures Gaming Tabletop Gaming Cosplay Photo 3AB 204 205 Time 4B 4C-3,4 4C-1 Time Time 611-612 615-617 618-620 Time Theater: 6A 604 613-614 310 2AB Time Gaming: 307-308 305 306 Gatherings (Location) Time Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. Also see corrections to the Cosplay Photo Gathering locations on p. 11. Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed See p. 11 for the key 7:00am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am to photo shoot locations. 7:30am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 10th - 11th (1 of 4) 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Elemental Gelade 1-5 To Heart 1-4 Fate/stay night 1-3 8:00am Voltron 1-5 New Legend of Shaolin Haruka Nogizaka’s Secret Closed for setup 8:00am 8:00am Main Stage Arena Stage Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Panels 4 (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-PG D, sub) (SC-PG VS, dub) (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-14) 1-4 4A 6E 6C 608-609 606 607 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am Time Time (SC-PG SD) Koichi Ohata Showcase: 9:00am Closed for setup Closed Closed -

Images of the Asia-Pacific War in Japanese Youth and Fan Culture

Title Subcultures of war : Images of the Asia-Pacific War in Japanese youth and fan culture Author(s) Jaworowicz-Zimny, Aleksandra Wiktoria Citation 北海道大学. 博士(教育学) 甲第13187号 Issue Date 2018-03-22 DOI 10.14943/doctoral.k13187 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/70733 Type theses (doctoral) File Information Aleksandra_Jaworowicz-Zimny.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Doctoral Thesis Subcultures of war. Images of the Asia‐Pacific War in Japanese youth and fan culture. 戦争のサブカルチャー。若者とファンの文化における 太平洋戦争のイメージ。 Aleksandra Jaworowicz‐Zimny Department of Multicultural Studies Graduate School of Education Hokkaido University January 10, 2018 Abstract Memories of the Asia‐Pacific War (1937‐1945) are constantly present in Japanese popular culture. Despite much research concerning representations of the war in mainstream culture, little is known about representations in amateur works. This dissertation analyzes images of war in Japanese fan productions, defined via a modified concept of the 'circuit of culture'. I focus on four forms: music, dōjinshi (fan comic books), fan videos and military cosplay. I identify three main concepts necessary in the analysis of war‐themed fan productions: kandō, nostalgia, and pop nationalism. Kandō is a strong emotional reaction to given content. Nostalgia allows idealization of the past and its perception according to the needs of the present day. Finally, pop nationalism is a trend of 'loving Japan' expressed though small things like support for Japanese sports, national symbols and Japanese products, but without explicit reference to historical consciousness or politics of the contemporary state. These three elements are recurring aspects of the fan productions discussed. -

Newsletter 07/05 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 07/05 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 153 - April 2005 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd In dieser Ausgabe: ein Exklusiv-Bericht vom WIDESCREEN WEEKEND in Bradford, England LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 07/05 (Nr. 153) April 2005 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, nicht verwendeten Szenen. Wer jetzt hat, der sollte sich schnellstmöglich nach liebe Filmfreunde! glaubt, dass sich Cameron noch einmal an Ersatz umschauen oder seine Gäste auf Kaum zu glauben: die TITANIC schwimmt seinem Magnum Opus mit der Schere zu Mitte Mai vertrösten. Das ist zwar sehr wieder! Nein, es handelt sich dabei nicht schaffen macht, der irrt. Cameron hat klar- schade, doch andererseits bietet die etwa um einen verspäteten Aprilscherz, gestellt, dass er mit der vorliegenden Terminverschiebung auch weiterhin die sondern um knallharte Fakten aus der Kinofassung mehr als zufrieden ist. Somit Möglichkeit, sich auf die Begegnung mit DVD-Welt. Einer Pressemitteilung zufolge wird es also keine ”Special Extended Ver- Lars von Triers Krankenhausgeschichte zu nämlich wird James Camerons sion” oder ähnlichen Schnickschnack ge- freuen! Und was könnte es schöneres ge- ”Oscar”prämiertes Meisterwerk im Okto- ben. Laut Pressemitteilung soll es jedoch ben als die Vorfreude auf ein geniales ber dieses Jahres in Form einer Special dem Betrachter möglich sein, die geschnit- Werk... Edition vom Stapel laufen. Und was die tenen Szenen während dem Film Fans ganz speziell freuen dürfte ist die hinzuzuschalten und so seine eigene Mögen Sie’s asiatisch? Tatsache, dass eigens für diese Special Schnittfassung zu generieren. -

La Liste Des Mangas Animés

La liste des mangas animés # 009-1 Eng Sub 17 07-Ghost Fre Sub 372 11eyes Fre Sub 460 30-sai no Hoken Taiiku Eng Sub 484 6 Angels Fre Sub 227 801 T.T.S. Airbats Fre Sub 228 .hack//SIGN Fre Sub 118 .hack//SIGN : Bangai-hen Fre Sub 118 .hack//Unison Fre Sub 118 .hack//Liminality Fre Sub 118 .hack//Gift Fre Sub 118 .hack//Legend of Twilight Fre Sub 118 .hack//Roots Fre Sub 118 .hack//G.U. Returner Fre Sub 119 .hack//G.U. Trilogy Fre Sub 120 .hack//G.U. Terminal Disc Fre Sub .hack//Quantum Fre Sub 441 .hack//Sekai no mukou ni Fre Sub _Summer Fre Sub 286 A A Little Snow Fairy Sugar Fre Sub 100 A Little Snow Fairy Sugar Summer Special Fre Sub 101 A-Channel Eng Sub 485 Abenobashi Fre Sub 48 Accel World Eng Sub Accel World: Ginyoku no kakusei Eng Sub Acchi kocchi Eng Sub Ace wo Nerae! Eng Sub Afro Samurai Fre Sub 76 Afro Samurai Resurrection Fre Sub 408 Ah! My Goddess - Itsumo Futari de Fre Sub 470 Ah! My Goddess le Film DVD Ah! My Goddess OAV DVD Ah! My Goddess TV (2 saisons) Fre Sub 28 Ah! My Mini Goddess TV DVD Ai Mai! Moe Can Change! Eng Sub Ai Yori Aoshi Eng Sub Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Eng Sub Aika Eng Sub 75 AIKa R-16 - Virgin Mission Eng Sub 425 AIKa Zero Fre Sub 412 AIKa Zero OVA Picture Drama Fre Sub 459 Air Gear Fre Sub 27 Air Gear - Kuro no Hane to Nemuri no Mori - Break on the Sky Eng Sub 486 Air Master Fre Sub 47 AIR TV Fre Sub 277 Aishiteruze Baby Eng Sub 25 Ajimu - Kaigan Monogatari Fre Sub 194 Aiura Fre Sub Akane-Iro ni Somaru Saka Fre Sub 387 Akane-Iro ni Somaru Saka Hardcore Fre Sub AKB0048 Fre Sub Akikan! Eng Sub 344 Akira Fre Sub 26 Allison to Lillia Eng Sub 172 Amaenaide Yo! Fre Sub 23 Amaenaide Yo! Katsu!! Fre Sub 24 Amagami SS Fre Sub 457 Amagami SS (OAV) Eng Sub Amagami SS+ Plus Fre Sub Amatsuki Eng Sub 308 Amazing Nurse Nanako Fre Sub 77 Angel Beats! Fre Sub 448 Angel Heart Fre Sub 22 Angel Links Eng Sub 46 Angel's Tail Fre Sub 237 Angel's Tail OAV Fre Sub 237 Angel's Tail 2 Eng Sub 318 Animation Runner Kuromi 2 Eng Sub 253 Ankoku Shinwa Eng Sub Ano hi mita hana no namae o bokutachi wa mada shiranai. -

Japan Media Arts Festival (Honorary Mention)

2002 (6th) Jury Recommended Works | MEDIA ARTSPLAZA 2002 (6th) Jury Recommended Works | Digital Art [Interactive] | Digital Art [Non-interactive] | | Animation | Manga | List | Web Title Author pF/plaNet Former doubleNegatives The Sonic Memorial Project Sue Johnson and Alison Cornyn Mid-Tokyo Maps Mori Building Co., Ltd ./logicaland m.gusberti/m.aschauer/n.thoenen/s.deinhofer Letca Films Abraham Espinosa sodaplay Soda Creative Ltd Sound Bum Sound Bum Project RAKU-GAKI NISHIDA Koj Pingpong Cube Taku Anekawa re-move lia the Cyber-Kitchen' Various Eidetic Memory Rick Mullarky charamil laboratory Recruit Co., Ltd./ Okamoto Hiroyuki db-db OUR DESIGN PLAYGROUND Francis Lam Installation Title Author BLIND ROBOT Frank Fietzek comtype Hirahara Makoto The Crossing Ranjit Makkuni cacktail of colors Tomoyuki Shigeta / Takanori Endo iow ... Peter Frucht A Planet -interactive cinema- ATSUKO UDA Cloak Yuka Wake, Takaumi Furuhashi Oral cavity TV game machine Kawarabuki Naoyuki Tokyo Local Webscape : The Air Side Of Web Site Satoru Sugihara streetscape iori nakai Machine 6.0 Thomas Kvam and Frode Oldereid Homo Indicium Ioannis C,Yessios Shadow Garden Zachary Booth Simpson Smoke Ring Takeshi Ishiguro database Adriana de Souza e Silva and Fabian Winkler Game Title Author Virtua Fighter 4 SEGA-AM2 http://plaza.bunka.go.jp/english/festival/sakuhin_backnumber/14/suisen/index.html- 9/24/2004 - 1 2002 (6th) Jury Recommended Works | MEDIA ARTSPLAZA KAZUMA KUJO:IREM SOFTWARE ENGINERRING ZETTAI ZETSUMEI TOSHI INC. Taiko no Tatsujin de Dodon ga Don Taiko no tatsujin project Masuya Oishi CHULIP YOSHIRO KIMURA rakugaki kingdom kamimura takeshi Animal Crossing Tezuka Takashi Animal Leader Matsumoto Gento Eternal Darkness Sanity's Requiem Denis Dyack Summer Holidays 20th Century 2 Kaz Ayabe hack//INFECTION BANDAI CO., LTD. -

The Drink Tank, and Let’S Move It

This issue is gonna be interesting. We’re got the Mo Starkey cover, we’ve got Taral, we’ve got 52 Weeks Tackling Anime and then there’s a wonderful piece from James! It’s a packed issue! So, Westercon. As I type this section, I’m at the Westercon 66 introductory meeting. I like Westercons, I’m the Fan GoH for WesterCon 67 (along with Cory Doctorow as Writer GoH, and the team from the PodCast Writing Excuses (including Mary Robinette Kowal, Brandon Sanderson, Howard Tayler and Dan Wells) well be there too!) and I’ve been to a bunch of them over the years. I have been concerned about the future of Wester- Con. I am most concerned about what’ll happen if there is no bid for a WesterCon. That worries me because there is no provision for what happens if there is a skipped WesterCon. I was in the bath and had an idea - What if we got rid of the bylaws and replaced them with just one phrase - ‘The LASFS Board of Directors may award a WesterCon at any time.” To me, this solves a number of problems, and admittedly it raises a couple of more. The biggest problem that I now realise is that the LASFS Board of Directors include some of the group that most would like to see WesterCon go away. It would make it easy to do something as radical as completely redesigning a WesterCon. It would get rid of all of the restrictions like being forced to host a Business Meeting or hold it over the 4th of July weekend, or not combine it with a regular running convention instead of being a stand-alone. -

The History of Xenogears and Xenosaga

Xenogears and Xenosaga Study Guide The History of Xenogears and Xenosaga Part 3: New Director Table of Contents: Introduction Part 1: XENOGEARS - Origins of the story - Developing the game - A fandom is born - Perfect Works / Episode I -- Transition towards "Xenosaga" Part 2: XENOSAGA - MonolithSoft's Project X - Unveiling the XENOSAGA project - Episode I: Der Wille zur Macht - Official Design Materials Part 3: XENOSAGA II & III - A new stance -- series cut down to 1/3 - Episode II: Jenseits von Gut und Bose - A(nother) remake - Episode III: Also Sprach Zarathustra - Complete and Perfect Guide Part 4: MONOLITHSOFT AND NINTENDO - Takahashi's reuse of the "Xeno-" name - Xenogears and Xenosaga news - Appendix: Links to referenced articles, interviews and sources Part 3: XENOSAGA II & III A new stance -- series cut down to 1/3 After Episode I, the staff at MSI decided to refresh the series and a transition within the company occured. Hirohide Sugiura (CEO) said in a May 2003 interview that this transition had everything to do with both Monolith's structure and where they wanted to take the Xenosaga series in the future. He had begun to feel that game creators were getting older and there weren't many younger ones coming out and if that keeps up, we'd never see a shift to a new generation, which he didn't think was healthy from an industry standpoint. So he decided to change the structure starting with Monolith Soft, his own company. He wanted to free Takahashi of his old position and let him work more freely as a creator and act more as the supervisor and provider of the original story. -

25 Years of the Great Cultural Donation by Japan

25 YEARS OF THE GREAT CULTURAL DONATION BY JAPAN REPUBLIC OF COLOMBIA Ministry of Foreign Affairs PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC Álvaro Uribe Vélez MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Fernando Araújo Perdomo VICE MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Camilo Reyes Rodríguez VICE MINISTER OF MULTILATERAL AFFAIRS Adriana Mejía Hernández SECRETARY GENERAL Martha Elena Díaz Moreno DIRECTOR OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS María Claudia Parías Durán ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Secretariat of Culture, Recreation and Sports EDITORIAL COORDINATION Editorial Committee – Ministry of Foreign Affairs PROOFREADING Marcela Giraldo Samper PRINTING National Printing Office of Colombia ISBN 978-958-8244-29-7 First Edition, 300 copies Bogotá, May 2008 ©TEXTS: MARGARITA POSADA JARAMILLO © PHOTOGRAPHS: VIVIAN FÖRSTER PRESENTATION Fernando Araújo Perdomo MEETING OF CULTURES Tolima Conservatory MUSIC EVERYWHERE Batuta Foundation A BANK THAT RADIATES CULTURE Luis Ángel Arango Library TV IS CULTURE Inravisión RTVC A SPACE FOR LIFE AND SOCIALIZATION Jorge Eliécer Gaitán Municipal Theater CALI IS CALI, THE REST… Municipal Cultural Center of Cali Los Cristales Open Air Theater Jorge Isaacs Theater A THEATER NAMED AFTER A PRESIDENT Guillermo León Valencia Municipal Theater THE GRANDFATHER OF ALL THEATERS Cristóbal Colón Theater THE MIRACLE OF COLLECTIVE MEMORY National Center for Restoration TO THE RHYTHM OF WINNERS National University Music Conservatory THE TIMELESSNESS OF BOOKS National Library of Colombia Center for Music Documentation A LIBERATOR WHO LASTS IN THE MEMORY Bolivar House Museum A GREAT THEATER