Magazine Pioneers: Form and Content in 1960S and 1970S Radicalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

Bottom-Line Pressures in Publishing: a Panel Discussion

BOTTOM-LINE PRESSURES IN PUBLISHING: A PANEL DISCUSSION http://www.najp.org This is an edited and abbreviated transcript of a National Arts Journalism Program panel on the effect of bottom-line pressures on the publishing industry held at Columbia University on April 17, 1998. Panelists: Susan Bergholz, literary agent based in New York City. Formerly a bookseller, Ms. Bergholz has also worked as a buyer for Endicott. Lee Buttala, Associate Editor at Alfred A. Knopf, where he has worked since 1995. Previous to that, he was an editor at Interview and Metropolitan Home magazines. Jeff Seroy, Vice President and Publicity Director, Farrar, Straus & Giroux. A graduate of Columbia University, Mr. Seroy was awarded a Kellett Fellowship for continuing studies at Cambridge University for the 1976-77 academic year, after which he entered the publishing industry. Elisabeth Sifton, Senior Vice President, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, and Publisher, Hill & Wang. Ms. Sifton has held editorial and executive positions at The Viking Press, Viking Penguin, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and Elisabeth Sifton Books, which won the Carey-Thomas Award for Creative Publishing in 1986. William B. Strachan, President and Director, Columbia University Press. Formerly editor in chief at Henry Holt, Mr. Strachan has worked at a number of other trade publishers throughout his career including Viking Press and Anchor Press. Moderators: Ruth Lopez, 1997-98 NAJP Fellow, Book Review editor at The Santa Fe New Mexican. Carlin Romano, 1997-98 NAJP Senior Fellow, literary critic, The Philadelphia -

Zachary M. Schrag Institutional Review Blog

Zachary M. Schrag Institutional Review Blog August 2012 – January 2017 This document contains all text appearing on the Institutional Review Blog, http://www.institutionalreviewblog.com/, from 31 August 2012 (the first entry after the previous archive) through the end of January 2017. Except where noted, all entries were written by Zachary M. Schrag, of the George Mason University Department of History and Art History. This version was prepared for archiving at the Mason Archival Repository Service (MARS), mars.gmu.edu. Readers are encouraged to cite individual blog entries, e.g., Zachary M. Schrag, "Smithsonian Frees Oral History, Journalism, and Folklore," Institutional Review Blog, 30 July 2010, http://www.institutionalreviewblog.com/2010/07/smithsonian-frees-oral-history.html Each entry in the Institutional Review Blog by Zachary M. Schrag is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. You are free: • to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: • Attribution — You must attribute Institutional Review Blog to Zachary M. Schrag (with link). Attribute this work: <div xmlns:cc="http://creativecommons.org/ns#" xmlns:dct="http://purl.org/dc/terms/" about="http://www.institutionalreviewblog.com/2006/12/introduction.html"><span property="dct:title">Institutional Review Blog</span> (<a rel="cc:attributionURL" property="cc:attributionName" href="http://institutionalreviewblog.com">Zachary M. Schrag</a>) / <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/3.0/">CC BY-NC-ND 3.0</a></div> • Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. • No Derivative Works — You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. -

Visualizing FASCISM This Page Intentionally Left Blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors

Visualizing FASCISM This page intentionally left blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors Visualizing FASCISM The Twentieth- Century Rise of the Global Right Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Julienne Alexander / Cover designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro and Haettenschweiler by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Eley, Geoff, [date] editor. | Thomas, Julia Adeney, [date] editor. Title: Visualizing fascism : the twentieth-century rise of the global right / Geoff Eley and Julia Adeney Thomas, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019023964 (print) lccn 2019023965 (ebook) isbn 9781478003120 (hardback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478003762 (paperback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478004387 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Fascism—History—20th century. | Fascism and culture. | Fascist aesthetics. Classification:lcc jc481 .v57 2020 (print) | lcc jc481 (ebook) | ddc 704.9/49320533—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023964 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023965 Cover art: Thomas Hart Benton, The Sowers. © 2019 T. H. and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by vaga at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. This publication is made possible in part by support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame. CONTENTS ■ Introduction: A Portable Concept of Fascism 1 Julia Adeney Thomas 1 Subjects of a New Visual Order: Fascist Media in 1930s China 21 Maggie Clinton 2 Fascism Carved in Stone: Monuments to Loyal Spirits in Wartime Manchukuo 44 Paul D. -

SMILING THROUGH the APOCALYPSE - Esquire in the Sixties

SMILING THROUGH THE APOCALYPSE - Esquire in the Sixties A Documentary by Tom Hayes 98 min / 2013 / English / Digital (DCP & BluRay) FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 / Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] Synopsis: SMILING THROUGH THE APOCALYPSE - Esquire in the Sixties traces the life of legendary Esquire Magazine Editor Harold Hayes. Twenty-five years after his father's passing, Hayes’ son Tom takes the viewer on a journey to understand how his father’s magazine became a galvanizing force in American culture, and the voice of an era. The film is a compelling story of challenge, triumph, and defeat, painting an explicit portrait of an era through a man who cultivated an extraordinary group of writers, photographers and artists, providing a vivid context for nothing less than the rebirth of American aesthetics. Featuring interviews with, Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Robert Benton, Peter Bogdanovich, Nora Ephron, Gore Vidal, Hugh Hefner and more. Director’s Bio: Born and raised in New York City, Tom Hayes is the son of the legendary magazine editor Harold Hayes and Broadway actress Suzette Meredith. After graduating from Wake Forest University in 1979, he assisted Academy Award nominated director Peter Bogdanovich on the film “They All Laughed” starring Audrey Hepburn. This on-set training earned him entre as an Associate Producer at CBS Cable for three years. Hayes then moved into independent television and film production, working on numerous news magazine stories, documentaries, TV movies and commercials. SMILING THROUGH THE APOCALYPSE - Esquire in the Sixties is his first feature film. -

Tom Wolfe Became…Tom Wolfe” by Michael Lewis, Vanity Fair, October 8, 2015 This Is a Really Long Piece—Much Longer Than the Usual Pieces Vanity Fair Publishes

Weekly What #6 Elaine Bennett’s analysis of “How Tom Wolfe Became…Tom Wolfe” by Michael Lewis, Vanity Fair, October 8, 2015 This is a really long piece—much longer than the usual pieces Vanity Fair publishes. I’m only going to share some excerpts with you here, but I hope you’ll seek out and read the whole thing: http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2015/10/how-tom-wolfe-became-tom-wolfe [Note: if you read the full piece, you’ll encounter some of the casual racism of the 1940s in Wolfe’s youthful writing as well as the pervasive elitism of New York in the…well…forever.] Excerpt #1—the opening of 2 sections of the article How Tom Wolfe Became…Tom Wolfe I was 11 or maybe 12 years old when I discovered my parents’ bookshelves. They’d been invisible right up to the moment someone or something told me that the books on them were stuffed with dirty words and shocking behavior—a rumor whose truth was eventually confirmed by Portnoy’s Complaint. The book I still remember taking down from the shelf was Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers. The only word in the title I understood was “the.” The cover showed a picture of a bored-looking blonde housewife nestled in the lap of a virile black man. It seemed just the sort of thing to answer some questions I had about the facts of life. It didn’t. Instead, it described a cocktail party given in the late 1960s for the Black Panthers by Leonard Bernstein in his fancy New York City apartment. -

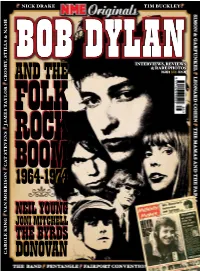

NME Dylan/Folk Rock Issue 2003

NICK DRAKE TIM BUCKLEY BOB DYLANBOB DYLAN INTERVIEWS, REVIEWS & RARE PHOTOS AND THE VOLUME 2 ISSUE 5 UK £ 5.99 & NASH STILLS CROSBY, FOLK ROCK BOOM 1964-1974 NEIL YOUNG JONI MITCHELL THE BYRDS CAROLE KING CAROLE MORRISON VAN STEVENS CAT DONOVAN TAYLOR JAMES DVD - EREDV519 Features the classic tracks 99.9F ˚, Marlene On The Wall, When Heroes Go Down, Left Of Center, Luka, Solitude Standing, Tom's Diner and many more. 2004 Includes bonus tracks from her concert DISTRIBUTED BY at the Montreux Festival in 2000. AVAILABLE AT eagle vision A DIVISION OF EAGLE ROCK ENTERTAINMENT LIMITED www.eagle-rock.com “FESTIVAL!” MURRAY LERNER’S CLASSIC FILM, originally released in 1967, is now on DVD for the first time. Filmed across four Newport Folk Festivals in the early sixties it combines live footage and interviews with the artists and with members of the audience. FEATURED ARTISTS INCLUDE BOB DYLAN • JOAN BAEZ • DONOVAN, PETER,PAUL & MARY • JOHNNY CASH, JUDY COLLINS and many more. EREDV499 DISTRIBUTED BY AVAILABLE FROM eagle vision A DIVISION OF EAGLE ROCK ENTERTAINMENT LTD www.eagle-rock.com Britain catches Dylanmania, Donovan versus Dylan, The Byrds fly in, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott reminisces, the great Protest Song debate, Barry McGuire heralds the ‘Eve Of Destruction’, Sonny & Cher conquer the charts, Simon & PAGES 6-39 Garfunkel forge sound out of silence Byrds banned in drug scandal, Dylan press deceptions and gig fracas, Simon & Garfunkel go “intellectual”, The Mamas And The Papas entertain The Beatles, Cat Stevens in “youth’s a drag” shocker, -

2018 Alumni Notes Newsletter

ALUMNI & FRIENDS OF ALUMNI NOTES FIORELLO H. LAGUARDIA HS OF spring 2018 MUSIC & ART AND PERFORMING ARTS “I love LaGuardia and all the values it stands for: excellence, acceptance, and unwavering support.” – Arto Kazakov (LaG ‘17), recipient of the Alumni & Friends Graduation Award for Technical Theater “At age 68 I can now say that my years at Music & Art were the grandest, most transformative and meaningful of my life.” – Lea Fridman (M&A ‘66) “I wouldn’t be who I am as an artist if I hadn’t had the opportunity to attend LaGuardia. ... LaGuardia has given students like me the chance to work in a ceramics studio, create sculptures, and make prints. I could have never imagined working with any of those various mediums, but thanks to LaGuardia and the Alumni & Friends of LaGuardia, that dream is made possible for every student in this school, and for generations to come.” – Keren Marshall (LaG ‘17), recipient of the M&A Class of 1945 Award “Thank you for recognizing my work and bringing me closer to my goals. Your award has given me a push forward in a time of self doubt and has inspired me to work my hardest and never give up on myself. I hope to one day make you as proud of me as I am of myself, and I strive to one day prove to you how much this means to me using more than just words.” – Monica Caicedo (LaG ‘19), recipient of the Sheila Stember Art Award “As life has moved on since graduation, I find that having had the M&A experience has contributed GREATLY to my life. -

Robert Frank Map and Chronology

8kjj[ :[jhe_j D[mOeha9_jo 9b[l[bWdZ 9^_YW]e IWd<hWdY_iYe ?dZ_WdWfeb_i IWdjW<[ Bei7d][b[i IWlWddW^ D[mEhb[Wdi >ekijed Ij$F[j[hiXkh] C_Wc_ 1924 1946 November 9: Robert Louis Frank is Makes spiral-bound book 40 Fotos, born in Zurich, Switzerland, the incorporating original photographs second son of Regina and Hermann in various genres. Frank. Travels to Milan, Paris, and Strasbourg. 1931 – 1937 May – August: Works for Graphic Attends Gabler School, Zurich. Atelier H., R. and W. Eidenbenz, Map and Basel. 1937 – 1940 Chronology Attends Lavater Secondary School, 1947 Zurich. February 19 or 20: Departs Antwerp Sarah Gordon and Paul Roth on S.S. James Bennett Moore bound for Rotterdam and New York City. 1940 March 14: Arrives in New York, finds 8kjj[ Studies French at the Institut an apartment opposite Rockefeller Jomini, Payerne. Center, and lives briefly with the Note on Chronology designer and photographer Herbert Matter and his wife, Mercedes, in This chronology focuses on Frank’s 1941 Greenwich Village. Later moves to 53 :[jhe_j early years, with an emphasis on January: Begins informal apprentice- East Eleventh Street in Manhattan. D[mOeha9_jo 9b[l[bWdZ activities and associations related ship with photographer and graphic 9^_YW]e Late March / early April: Visits Henri to The Americans. It is indebted designer Hermann Segesser in Cartier-Bresson exhibition at the to Stuart Alexander, Robert Frank: Zurich (until March 1942). IWd<hWdY_iYe Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). ?dZ_WdWfeb_i A Bibliography, Filmography, and September – December: Serves as still Exhibition Chronology 1946 – 1985 April: Hired by Alexey Brodovitch photographer for film Landammann (Tucson: Center for Creative Photog- as an assistant photographer at Stauffacher. -

Understanding Popular Music, Second Edition

Understanding Popular Music Understanding Popular Music is an accessible and comprehensive introduction to the history and meaning of popular music. It begins with a critical assessment of the different ways in which popular music has been studied and examines the difficulties and debates which surround the analysis of popular culture and popular music. Drawing on the recent work of music scholars and the popular music press, Roy Shuker explores key subjects which shape our experience of music, including music production, the music industry, music policy, fans, audiences and subcultures, the musician as ‘star’, music journalism, and the reception and consumption of popular music. This fully revised and updated second edition includes: • case studies and lyrics of artists such as Shania Twain, S Club 7, The Spice Girls and Fat Boy Slim • the impact of technologies including on-line delivery and the debates over MP3 and Napster • the rise of DJ culture and the changing idea of the ‘musician’ • a critique of gender and sexual politics and the discrimination which exists in the music industry • moral panics over popular music, including the controversies surrounding artists such as Marilyn Manson and Eminem • a comprehensive discography, guide to further reading and directory of websites. Roy Shuker is Associate Professor in Media Studies at Massey University, New Zealand. He is the author of Key Concepts in Popular Music (Routledge 1998). LONDON AND NEW YORK Understanding Popular Music Second edition I Roy Shuker First published 1994 now known or hereafter invented, including by Routledge photocopying and recording, or in any 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Eliot Elisofon

Eliot Elisofon: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Elisofon, Eliot Title: Eliot Elisofon Papers and Photography Collection Dates: 1930-1988 (bulk 1942-1973) Extent: 144 boxes, 2 scrapbook boxes, 2 oversized boxes, 3 glass slide boxes (60.5 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this American photographer and author contains photographs, transparencies, slides, negatives, films, research material, notes, photo captions, logbooks, correspondence, agreements and other documents, drafts, proofs, tearsheets, clippings, scrapbooks, catalogs, sketchbooks, and artifacts documenting his entire career. Language English. Arrangement Organization by Format Storage Black and white prints and paper material, boxes 1-73 Color transparencies and prints, boxes 74-121 Black and white negatives, boxes 122-144 Glass slides, boxes 145-147 Oversize material, boxes O1 and O2 Scrapbooks, boxes S1 and S2 Due to size, this inventory has been divided into three separate units which can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted text below: Eliot Elisofon Papers--Series I. [Part I] Eliot Elisofon Papers--Series I. (continued)[Part II] Eliot Elisofon Papers--Series II.-Indexes [Part III] [This page] Elisofon, Eliot Series II. Film and Television Projects, 1953-1973, 1986 "Noa Noa," proposed film project on Gauguin, by James Agee Gauguin, [Painting, "D'ou venons-nous? Que sommes-nous? Où allons-nous?" box-folder ], 5x7 color trans. (9 exp.), [Jan. 1955 or July 1959?] 120.10 box-folder Correspondence, draft of screenplay, -

Book World Luncheon, New York City, January 13, 1969

Book & Author Luncheon Sponsored by American Booksellers Association Book World (Washington Post & Chicago Tribune) National Book Committee 1968-1969 Luncheons Grand Ballroom, Waldorf-Astoria Master of Ceremonies MAURICE DOLBIER Literary Editor, Providence' Journal Program Director BELLE ROSENBAUM Associate Editor, BOOK WORLD, MARYA MANNES, author of GEORGE PLIMPTON, author of ALISTAIR COOKE, author of "Talk HUBERT H. HUMPHREY, author Washington Post, "The Bogey Man", participated as an About America", is chief American of "Beyond Civil Rights : A New Day of "They" is a commentator and critic Chicago Tribune of our cultural and literary life. amateur in three famous golf correspondent for The Guardian of Equality", was a leader of the civi l England. Last March he delivered his She has written social satire and satiric tournaments, the Bing Crosby National rights forces in the Senate, and as lOOOth "Letter From America" for political verse and two books of essays, Pro-amateur in Monterey, the Bob Hope Desert Classic in Palm Springs the British Broadcasting Corporation. Vice-President of the United States was "More in Anger" and "But Will It and the Lucky International in the flo or manager for the civil ri ghts His book is a selection of 41 of his Sell". "They", a novel in journal San Francisco - a month on the broadcasts in which he explains America legislation. His book is an analysis of the form, projects a computerized society professional golf circuit to capture the to Englishmen. Such things as Beizbol, "ugly riots, ugly rumors, ugly racisms in which all men and women past fifty atmosphere and learn from first hand New England town meetings, American jOSEPH DUFFY that divide and frighten our people", and are sequestered as rejects from society.