Chapter 1: Introduction 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGRICULTURAL. SYSTEMS of PAPUA NEW GUINEA Ing Paper No. 14

AUSTRALIAN AtGENCY for INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGRICULTURAL. SYSTEMS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ing Paper No. 14 EAST NIEW BRITAIN PROVINCE TEXT SUMMARIES, MAPS, CODE LISTS AND VILLAGE IDENTIFICATION R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, R.L. Hide, D. Fritsch, T. Geob, R. Grau, 5. Heai, P. Hobsb21wn, G. Ling, S. Lyon and M. Poienou REVISED and REPRINTED 2002 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY PAPUA NEW GUINEA DEPARTMENT OF AGRI LTURE AND LIVESTOCK UNIVERSITY OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Papers I. Bourke, R.M., B.J. Allen, P. Hobsbawn and J. Conway (1998) Papua New Guinea: Text Summaries (two volumes). 2. Allen, BJ., R.L. Hide. R.M. Bourke, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, E. Lowes, T. Nen, E. Nirsie, J. Risimeri and M. Woruba (2002) East Sepik. Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. 3. Bourke, R.M., BJ. Allen, R.L. Hide, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, E. Lowes, T. Nen, E. Nirsie, J. Risimeri and M. Woruba (2002) West Sepik Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. 4. Allen, BJ., R.L. Hide, R.M. Bourke, W. Akus, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, G. Ling and E. Lowes (2002) Western Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. 5. Hide, R.L., R.M. Bourke, BJ. Allen, N. Fereday, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, E. Lowes and M. Woruba (2002) Gulf Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. 6. Hide, R.L., R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, T. Betitis, D. Fritsch, R. Grau. L. Kurika, E. Lowes, D.K. Mitchell, S.S. -

Comments on Sorcery in Papua New Guinea

GIALens. (2010):3. <http://www.gial.edu/GIALens/issues.htm> Comments on Sorcery in Papua New Guinea KARL J. FRANKLIN, PH. D. Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics and SIL International ABSTRACT Variations of sorcery and witchcraft are commonly reported in Papua New Guinea. The Melanesian Institute (in Goroka, PNG) has published two volumes (Zocca, ed. 2009; Bartle 2005) that deal extensively with some of the issues and problems that have resulted from the practices. In this article I review Zocca, in particular, but add observations of my own and those of other authors. I provide a summary of the overall folk views of sorcery and witchcraft and the government and churches suggestions on how to deal with the traditional customs. Introduction Franco Zocca, a Divine Word Missionary and ordained Catholic priest from Italy with a doctorate in sociology, has edited a monograph on sorcery in Papua New Guinea (Zocca, ed. 2009). Before residing in PNG and becoming one of the directors of the Melanesian Institute, Zocca worked on Flores Island in Indonesia. His present monograph is valuable because it calls our attention to the widespread use and knowledge of sorcery and witchcraft in PNG. Zocca’s monograph reports on 7 areas: the Simbu Province, the East Sepik Province, Kote in the Morobe Province, Central Mekeo and Roro, both in the Central Province, Goodenough Island in the Milne Bay Province and the Gazelle Peninsula in the East New Britain Province. The monograph follows Bartle’s volume (2005), also published by the Melanesian Institute. Before looking at Zocca’s volume and adding some observations from the Southern Highlands, I include some general comments on the word sanguma . -

PONERA Abeillei André, 1881; See Under HYPOPONERA. Abyssinica Guérin-Méneville, 1849; See Under MEGAPONERA

BARRY BOLTON’S ANT CATALOGUE, 2020 PONERA abeillei André, 1881; see under HYPOPONERA. abyssinica Guérin-Méneville, 1849; see under MEGAPONERA. abyssinica Santschi, 1938; see under HYPOPONERA. acuticostata Forel, 1900; see under PSEUDONEOPONERA. aemula Santschi, 1911; see under HYPOPONERA. aenigmatica Arnold, 1949; see under EUPONERA. aethiopica Smith, F. 1858; see under STREBLOGNATHUS. aethiopica Forel, 1907; see under HYPOPONERA. *affinis Heer, 1849; see under LIOMETOPUM. affinis. Ponera affinis Jerdon, 1851: 118 (w.) INDIA (Karnataka/Kerala; “Malabar”). Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated). Type-locality: India: Malabar (T.C. Jerdon). Type-depository: unknown (no material known to exist). [Duplicated in Jerdon, 1854b: 102.] [Unresolved junior primary homonym of *Ponera affinis Heer, 1849: 147 (Bolton, 1995b: 360).] Status as species: Smith, F. 1858b: 84; Mayr, 1863: 447; Smith, F. 1871a: 320; Dalla Torre, 1893: 37; Emery, 1911d: 116; Chapman & Capco, 1951: 68; Tiwari, 1999: 29. Unidentifiable to genus; incertae sedis in Ponerinae: Emery, 1911d: 116. Unidentifiable to genus; incertae sedis in Ponera: Bolton, 1995b: 360. Distribution: India. agilis Borgmeier, 1934; see under HYPOPONERA. aitkenii Forel, 1900; see under HYPOPONERA. albopubescens Menozzi, 1939; see under HYPOPONERA. aliena Smith, F. 1858; see under HYPOPONERA. alisana. Ponera alisana Terayama, 1986: 591, figs. 1-5 (w.q.) TAIWAN. Type-material: holotype worker, 5 paratype workers, 4 paratype queens. Type-locality: holotype Taiwan: Chiayi Hsien, Fenchihu (1400 m.), 3.viii.1980 (M. Terayama); paratypes with same data. Type-depositories: NSMT (holotype); NIAS, NSMT, TARI (paratypes). Leong, Guénard, et al. 2019: 27 (m.). Status as species: Bolton, 1995b: 360; Xu, 2001a: 53 (in key); Xu, 2001c: 218 (in key); Lin & Wu, 2003: 68; Terayama, 2009: 109; Yoshimura, et al. -

Philippine Currency in Circulation

SAE./No.92/October 2017 Studies in Applied Economics DID THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS HAVE A CURRENCY BOARD DURING THE AMERICAN COLONIZATION PERIOD? Ryan Freedman Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise Subsequently published in KSP Journals, September 2018 Did the Philippine Islands Have a Currency Board during the American Colonization Period? By Ryan Freedman Copyright 2017 by Ryan Freedman. This work may be reproduced provided that no fee is charged and the original source is properly credited. About the series The Studies in Applied Economics series is under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Johns Hopkins institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise ([email protected]). This working paper is one in a series on currency boards. The currency board working papers will fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of the subject. The authors are mainly students at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Some performed their work as research assistants at the Institute. About the author Ryan Freedman ([email protected]) is a senior at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore pursuing degrees in Applied Mathematics and Statistics and in Economics. He wrote this paper while serving as an undergraduate researcher at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise during the spring of 2017. He will graduate in May 2018. Abstract The Philippine monetary system and data from 1903-1948 are examined, using general observations and statistical tests to determine to what extent the system operated as a currency board. -

Town of Manilla V. Broadbent Land Company : Reply Brief Utah Supreme Court

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Utah Supreme Court Briefs 1990 Town of Manilla v. Broadbent Land Company : Reply Brief Utah Supreme Court Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_sc1 Part of the Law Commons Original Brief Submitted to the Utah Supreme Court; digitized by the Howard W. Hunter Law Library, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; machine-generated OCR, may contain errors. McKeachnie; Allred; Bunnell; Attorneys for Respondent. Van Waoner; Lewis T. Stewvens; Craig W. Anderson; Kristin G. Brewer; Clyde, Pratt& noS w; Attorneys for Appellant. Recommended Citation Reply Brief, Town of Manilla v. Broadbent Land Company, No. 900007.00 (Utah Supreme Court, 1990). https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_sc1/2820 This Reply Brief is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Supreme Court Briefs by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. Policies regarding these Utah briefs are available at http://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/utah_court_briefs/policies.html. Please contact the Repository Manager at [email protected] with questions or feedback. UTAH UTAH SUPREME COURT DOCIWNT KFU BRIEF 45.9 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STA^TE OF UTAH .S9 DOCKET NO. 00O00 TOWN OF MANILA REPLY BRIEF AND RESPONSE Plaintiff and Respondent TO AMICUS BRIEF v. BROADBENT LAND COMPANY Defendant and Appellant. Case No. 900007 00O00 Interlocutory Appeal Pursuant to Rule 54(b) of the Utah Rules of Civil Procedure from Findings, Judgments and Orders of the Eighth Judicial District Court in and for Daggett) County. -

Sorcery and Animism in a South Pacific Melanesian Context 2

Humble: Sorcery and Animism in a South Pacific Melanesian Context 2 GRAEME J. HUMBLE Sorcery and Animism in a South Pacific Melanesian Context We had just finished our weekly shopping in a major grocery store in the city of Lae, Papua New Guinea (PNG). The young female clerk at the checkout had scanned all our items but for some reason the EFTPOS ma- chine would not accept payment from my bank’s debit card. After repeat- edly swiping my card, she jokingly quipped that sanguma (sorcery) must be causing the problem. Evidently the electronic connection between our bank and the store’s EFTPOS terminal was down, so we made alternative payment arrangements, collected our groceries, and went on our way. On reflection, the checkout clerk’s apparently flippant comment indi- cated that a supernatural perspective of causality was deeply embedded in her world view. She echoed her wider society’s “existing beliefs among Melanesians that there was always a connection between the physical and the spiritual, especially in the area of causality” (Longgar 2009:317). In her reality, her belief in the relationship between the supernatural and life’s events was not merely embedded in her world view, it was, in fact, integral to her world view. Darrell Whiteman noted that “Melanesian epistemology is essentially religious. Melanesians . do not live in a compartmentalized world of secular and spiritual domains, but have an integrated world view, in which physical and spiritual realities dovetail. Melanesians are a very religious people, and traditional religion played a dominant role in the affairs of men and permeated the life of the commu- nity” (Whiteman 1983:64, cited in Longgar 2009:317). -

Dentition of Watom Island, Bismarck Archipelago, Melanesia

Records of the Australian Museum (1989) Vol. 41: 293-296. ISSN 0067 1975 293 Dentition of Watom Island, Bismarck Archipelago, Melanesia CHRISTY G. TURNER 11 Department of Anthropology, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85287-2402 USA. ABSTRACT. Teeth belonging to two adults excavated from the Lapita level occupation of Watom Island (ca. 2,300 years before present [YBP]) are described and compared with three large dental series from New Britain, recent Thailand, and Mokapu, Hawaii. As far as can be determined from a sample of two individuals, the Watom teeth appear to be more like those from New Britain than Thailand or Hawaii. All teeth are free of dental caries, hinting that the Watom diet was not overly dependent on sticky carbohydrate foodstuffs. TURNER, CHRISTY G., n, 1989. Dentition of Watom Island, Bismarck Archipelago, Melanesia. Records of the Australian Museum 41(3): 293-296. The current anthropological view about the origin of because dental features such as incisor shovelling, cu~p Polynesians recognises a link between a pottery type numbers and groove patterns are evolutionarily stable due called Lapita ware and the first settlements in Polynesia to their polygenic inheritance. Even in very small (Howells, 1973; Green, 1979; Bellwood, 1979). This ceramic populations, genetic drift has only a minimal effect, and type has been found in several archaeological sites in major environmental shifts have almost no identifiable Melanesia, suggesting that Polynesians originated from the selective effect in blocks of time involving less than 5,000 Melanesian gene pool. However, various physical years. anthropological studies have shown that Polynesian Given the theoretical importance of the Lapita-first skeletal and dental features are more like those of south Polynesian correspondence, and the methodological east Asians than Melanesians. -

Foods and Food Adulterants : Part Seventh : Tea, Coffee and Cocoa

Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices : U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. DITISIOX OF CHEMISTRY. BULLETIN No. 13. FOODS AXD FOOD ADULTEPvAi^TS, IXTESTIGATIOXS MADE rXDER IHRECTIOX OF H. ^V. AVILEY, Chief Chkmist. PART SEVENTH. Tea, Coffee, and Cocoa Preparations. GUILFORD L. SPENCER, Assistant Chemist, TTIIH THE COLLAB'JEATipX OF MR. ERTIX E. EWELL. PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE SECRETARY OF AGRICULTURE. ^VASHIXGTOX G-OYERX:\rEXT PRI>'TINa OFFICE, 1892. X U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. DIVISION OF CHEMISTEY. BULLETIN No. 13. FOODS AND FOOD adultera:n'ts, IXVESTIGATIONS MADE TNDEK DIRECTION OF Chief Chemist. f • PART SEVENTH. Tea, Coffee, and Cocoa Preparations, BY GUILFORD L. SPENCER, Assistant Chemist, WITH THE COLLABOKATION OF MK, EPyVIN E, EWEJ,!,. PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE SECRETARY OF ACiRICULTURE. WASHIXGTOX: GDVKKNXENT PRINTING OFFICE 1892. TARLl: OF COXTEXTS. Page. Letter of trausmittal V Letter of submittal - vii Tea - 875 Statistics of tea consumption 875 General classification 875 Methods of manufacture 876 Black teas 876 Gre«^n tea 878 Adulteration—definition 879 Adulteration—methods 880 Detection of facing 881 Spent or exhausted leaves 882 Foreign leaves 883 Foreign astringents 885 Added mineral matter 885 Lie tea 886 General remarks on tea adulterants 886 General statements concerning the constituents of teas 887 Analytical methods 889 General remarks to analysts 892 Report of the examination of teas bou<rht in ilic oiv'i market 892 Conclusion 898 Cofl^e - 899 Statistics of consumption 899 General statements 900 Chemical composition 901 Methods of analysis 907 Adulteration—definition 908 Adulterants and their detection 909 Substitutes for coffee 914 Imitation coffees 915 Detection of imitation coffees . -

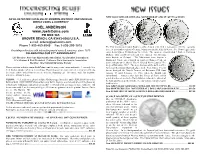

Joel Anderson P.O

NEW 2020 COINS OF GRENADA, MONTSERRAT AND ST. KITTS & NEVIS AN ILLUSTRATED CATALOG OF MODERN, HISTORIC AND UNUSUAL WORLD COINS & CURRENCY JOEL ANDERSON www.JoelsCoins.com PO BOX 365 GROVER BEACH, CA 93483-0365 U.S.A. e-mail: [email protected] Phone 1-805-489-8045 Fax 1-805-299-1818 The East Caribbean Central Bank recently released new 2020 1 troy ounce .999 fine coins for Providing collectors with interesting world coins & currency, since 1970 three of its member nations: Grenada, Montserrat and St. Kitts & Nevis. The 39mm legal tender CELEBRATING OUR 51ST ANNIVERSARY! coins depict Queen Elizabeth on the reverse. The coins are denominated 2 Eastern Caribbean Dollars. Only 25,000 of each coin were minted. The Grenada Life Member: American Numismatic Association, Numismatics International issue depicts an Octopus. The Montserrat issue depicts a Life Member & Past President: California State Numismatic Association Montserrat Oriole on a branch in front of Chances Peak, an Member: International Banknote Society active volcano on the island. The St. Kitts & Nevis features "The Siege of Brimstone Hill". The siege was one of the battles of the Please visit our website: www.JoelsCoins.com for many more coins and notes. I can only fit a American Revolution that took place in the West Indies. French very limited number of items in a catalog. If ordering on line, you may enter items directly into forces besieged the British Fortress of Brimstone Hill from the secure online order form or use the web site shopping cart. Of course, mail, fax or phone January 19 until February 17, 1782, when the British fort orders are always welcome. -

Soft Currencies, Cash Economies, New Monies: Past and Present

Soft currencies, cash economies, new monies: Past and present Jane I. Guyer1 Department of Anthropology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218 This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2008. Contributed by Jane I. Guyer, December 2, 2011 (sent for review August 16, 2011) Current variation in the forms of money challenges economic mediation to be examined in their own terms, alongside eco- anthropologists and historians to review theory and comparative nomic analyses based on the reductive assumptions of currency findings on multiple currency systems. There are four main sections uniformity and frictionless equivalence established through to the paper devoted to (i) the present continuum of hard to soft competitive market processes. The borders that we focus on are currencies as an instance of multiplicity, including discussion of dif- social and between communities of currency users. The thresh- ferent combinations of the classic four functions of money, espe- olds are conceptual and institutional between distinctive ca- cially the relationship between store of value and medium of pacities of different moneys, often implicating different moral exchange; (ii) the logic of anthropological inquiry into multiple cur- economies of fairness (in the short run) and transcendence (in rency economies; (iii) the case of the monies of Atlantic Africa, ap- the long run). The historical shifts are moments when combi- plying the analytics of exchange rates as conversions to African nations of attributes are brought into open question and sub- transactions; and (iv) the return to economic life in a present day mitted to deliberate reconfiguration. -

Town of Manilla V. Broadbent Land Company : Amicus Brief Utah Supreme Court

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Utah Supreme Court Briefs 1990 Town of Manilla v. Broadbent Land Company : Amicus Brief Utah Supreme Court Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_sc1 Part of the Law Commons Original Brief Submitted to the Utah Supreme Court; digitized by the Howard W. Hunter Law Library, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; machine-generated OCR, may contain errors. McKeachnie Allred & Bunnell; Gayle McKeanchnie; Clark Allred; David L. Church; Attorneys for Respondent. Van Waoner; Lewis T. Stevens; Craig W. Anderson; Kristin G. Brewer; Clyde, Pratt & noS w; Edward W. Clyde; Attorneys for Appellant. Recommended Citation Legal Brief, Town of Manilla v. Broadbent Land Company, No. 900007.00 (Utah Supreme Court, 1990). https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_sc1/2818 This Legal Brief is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Supreme Court Briefs by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. Policies regarding these Utah briefs are available at http://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/utah_court_briefs/policies.html. Please contact the Repository Manager at [email protected] with questions or feedback. UTAH NT D< r i BRItf. 45.9 S9 ^(Ztt?^ PACKET NO. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF UTAH TOWN OF MANILA AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF Plaintiff and Respondent vs. BROADBENT LAND COMPANY Case No. 900007 Defendant and Appellant. Interlocutory Appeal Pursuant to Rule 54(b) of the Utah Rules of Civil Procedure from Findings, judgments and orders of the Eighth Judicial District Court in and for Daggett County. -

Strategic Regulation of Alternative Currencies

Strategic Regulation of Alternative Currencies Caitlin T. Ainsley∗ Abstract Recent technological advances in digital banking and currency have brought increased attention to the states’ tenuous monopoly control over domestic currencies. Histori- cally, instances in which either privately-issued or foreign “alternative” currencies have successfully entered circulated have often been viewed as state regulatory failures or signs of monetary incompetence. In this paper, I put forth a theory that challenges this understanding of currency regulation and highlights potential advantages for states to tacitly permit an alternative currency to circulate alongside their own. With a search- theoretic model of domestic exchange, I demonstrate how periodic non-regulation of alternative currencies can be part of a coherent state regulatory strategy. Using the intuition derived from the model, I then provide novel interpretations of two historical case studies, examining both the process of monetary consolidation in the British Pro- tectorate of Southern Nigeria as well as restrictions on local scrip currencies during the Great Depression in Austria. ∗Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Washington. cains- [email protected] Scholars of political economy and state-building have long recognized the importance of states’ monopoly control over national currencies. In addition to the straightforward returns from seigniorage, it is argued that state control over the medium of exchange facilitates the emergence of domestic markets, makes possible macroeconomic stabilization and nationwide taxation programs, and contributes to the formation of a national identity (Helleiner 2003). Unsurprisingly given the well-documented benefits states accrue from their control of national currency, laws restricting or outright prohibiting the use of alternative private and foreign currencies for domestic exchange are ubiquitous.