Notes on Three Cuban Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIRDCONSERVATION the Magazine of American Bird Conservancy Fall 2016 BIRD’S EYE VIEW a Life Shaped by Migration

BIRDCONSERVATION The Magazine of American Bird Conservancy Fall 2016 BIRD’S EYE VIEW A Life Shaped By Migration The years have rolled by, leaving me with many memories touched by migrating birds. Migrations tell the chronicle of my life, made more poignant by their steady lessening through the years. still remember my first glimmer haunting calls of the cranes and Will the historic development of of understanding of the bird swans together, just out of sight. improved relations between the Imigration phenomenon. I was U.S. and Cuba nonetheless result in nine or ten years old and had The years have rolled by, leaving me the loss of habitats so important to spotted a male Yellow Warbler in with many memories touched by species such as the Black-throated spring plumage. Although I had migrating birds. Tracking a Golden Blue Warbler (page 18)? And will passing familiarity with the year- Eagle with a radio on its back Congress strengthen or weaken the round and wintertime birds at through downtown Milwaukee. Migratory Bird Treaty Act (page home, this springtime beauty was Walking down the Cape May beach 27), America’s most important law new to me. I went to my father for each afternoon to watch the Least protecting migratory birds? an explanation of how I had missed Tern colony. The thrill of seeing this bird before. Dad explained bird “our” migrants leave Colombia to We must address each of these migration, a talk that lit a small pour back north. And, on a recent concerns and a thousand more, fire in me that has never been summer evening, standing outside but we cannot be daunted by their extinguished. -

Cuba Trip Report Jan 4Th to 14Th

Field Checklist to the Birds of Cuba Cuba Trip Report Jan 4th to 14th 1 Field Checklist to the Birds of Cuba Cuba Bird List Species Scientific Name Seen Heard Order ANSERIFORMES Family Anatidae Ducks, Geese, Swans 1. West Indian Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna arborea • 2. Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor 3. American Wigeon Anas americanas 4. Wood Duck Aix sponsa 5.Blue-winged Teal Anas discors • 6. Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata • 7. White-cheeked Pintail Anas bahamensis 8. Northern Pintail Anas acutas 9. Green-winged Teal Anas carolinensis 10. Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris 11.Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis 12. Hooded Merganser Lophodytes cucullatus 13. Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator 14. Masked Duck Nomonyx dominicus 15. Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Order GALLIFORMES Family Phasianidae Pheasant, Guineafowl 16. Helmeted Guineafowl (I) • Family Odontophoridae New World Quail 17. Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus cubanensis Order PODICIPEDIFORMES Grebes 18. Least Grebe Tachybaptus dominicus • 19. Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps • Order CICONNIIFORMES Family Ciconiidae Storks 20. Wood Stork Mycteria americana 2 Field Checklist to the Birds of Cuba Cuba Bird List Species Scientific Name Seen Heard Order SULIFORMES Family Fregatidae Frigatebirds 21. Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens • Family Sulidae Boobies, Gannets 22. Brown Booby Sula leucogaster Family Phalacrocoracidae Cormorants 23. Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasiliannus • 24. Double-crested Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus • Family Anhingidae Darters 25. Anhinga Anhinga anhinga • Order PELECANIFORMES Family Pelecanidae Pelicans 26. American White Pelican Pelecanus erythrorhynchos 27. Brown Pelican Pelecanus occidentalis • Family Ardeidae Herons, Bitterns, Allies 28. Least Bittern Ixobrychus exilis • 29. Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias • 30. Great Egret Ardea alba • 31. Snowy Egret Egretta thula • 32. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Wetland Aliens Cause Bird Extinction

PRESS RELEASE Embargoed until 00:01 GMT on 26 May 2010 Wetland aliens cause bird extinction Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, 26 May, 2010 (IUCN/BirdLife) - BirdLife International announces today, in an update to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ for birds, the extinction of Alaotra Grebe Tachybaptus rufolavatus. Restricted to a tiny area of east Madagascar, this species declined rapidly after carnivorous fish were introduced to the lakes in which it lived. This, along with the use of nylon gill-nets by fisherman which caught and drowned birds, has driven this species into the abyss. “No hope now remains for this species. It is another example of how human actions can have unforeseen consequences”, says Dr Leon Bennun, BirdLife International’s Director of Science, Policy and Information. “Invasive alien species have caused extinctions around the globe and remain one of the major threats to birds and other biodiversity.” Another wetland species suffering from the impacts of introduced aliens is Zapata Rail Cyanolimnas cerverai from Cuba. It has been uplisted to Critically Endangered and is under threat from introduced mongooses and exotic catfish. An extremely secretive marsh-dwelling species, the only nest ever found of this species was described by James Bond, a Caribbean ornithologist and the source for Ian Fleming’s famous spy’s name. And it’s not just aliens. Wetlands the world over, and the species found in them, are under increasing pressures. In Asia and Australia, numbers of once common wader species such as Great Knot Calidris tenuirostris and Far Eastern Curlew Numenius madagascariensis are dropping rapidly as a result of drainage and pollution of coastal wetlands. -

Zapata Rail (Cyanolimnas Cerverai) Conservation Concern Category: Highest Concern

Zapata Rail (Cyanolimnas cerverai) Conservation Concern Category: Highest Concern Population Trend (PT) Breeding Distribution (BD) Declining—(Delany and Scott 2002; Birdlife International 2005) Zapata Swamp: W Central Cuba (Delany and Scott 2002) “species was easily found in 1931…subsequently there were no records, despite “occurs in 1,010 km2 on northern side of the occasional searches…bird’s former distribution was 4,500 km2 Zapata Swamp, south-west Cuba…” (Birdlife wider…” (Taylor 1998) International 2005) “species is more common than previously 21,900 km2 (plan area distribution; estimated thought…still qualifies as Endangered because it is from range maps) confined to a single area, where habitat loss and predation are almost certainly resulting in reduction of its very small range and population.” …decline of 1 to 9% BD FACTOR SCORE=5 over 10 years…” (Birdlife International 2005) Non-breeding Distribution (ND) PT FACTOR SCORE=5 Zapata Swamp: W Central Cuba (Delany and Population Size (PS) Scott 2002) 250-1,000 individuals (Delany and Scott 2002; 2 Occurs in 1,010 km on northern side of the Birdlife International 2005) 2 4,500 km Zapata Swamp, south-west Cuba.” (Birdlife “very few records in recent decades suggest that International 2005) its population is very small…” (Taylor 1998) 21,900 km2 (plan area distribution; estimated from range maps) PS FACTOR SCORE=4-5 ND FACTOR SCORE=5 Threats to Breeding Populations (TB) “extensive grass-cutting for roof thatch…most serious threats appear to be dry-season burning of References: habitat…introduced predators (mongoose, rat)…small areas have been drained…” (Taylor 1998) Delany, S. -

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

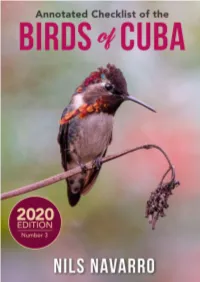

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba No. 2, 2018

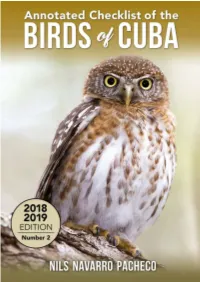

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 2 2018-2019 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Cuban Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium siju), Peralta, Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2017 Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2018 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2018 ISBN: 9781790608690 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. He is a freelance author and an internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as curator of the herpetological collection of the Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he described several new species of lizards and frogs for Cuba. Nils has been travelling throughout the Caribbean Islands and Central America working on different projects related to the conservation of biodiversity, with a particular focus on amphibians and birds. He is the author of the book Endemic Birds of Cuba, A Comprehensive Field Guide, which, enriched by his own illustrations, creates a personalized field guide structure that is both practical and useful, with icons as substitutes for texts. -

Threatened Birds of the Americas

ZAPATA RAIL Cyanolimnas cerverai I7 This apparently flightless marsh-dwelling rail remains known from only two sites within the Zapata Swamp, Cuba, where it is assumed to have suffered particularly from dry-season burning of habitat and perhaps also from introduced predators. DISTRIBUTION The Zapata Rail is endemic to Cuba, and for many years since it was first described in 1927 it was believed to occur only in a very restricted area about 1.5 km north of Santo Tomás (22°24’N 81°25’W in OG 1963a), Matanzas province (Barbour and Peters 1927, Garrido and García Montaña 1975). However, Barbour's (1928) surmise that the species would be found elsewhere in the Zapata area was borne out in June 1978 when a bird was observed in one of the channels leading to Guamá village (in the south-eastern corner of Laguna del Tesoro (22°21’N 81°07’W in OG 1963a) and a young bird was photographed at Guamá, Laguna del Tesoro, on 12 June 1978 (Clements 1979, Garrido 1985, J. F. Clements in litt. 1991), this new locality being about 65 km from Santo Tomás (Bond 1985). Fossil bones from cave deposits in Pinar del Río province and on the Isle of Pines (Isla de la Juventud) have been attributed to this species (Olson 1974), suggesting a wider former distribution (Garrido 1985). Few specimens have been taken; those in ANSP and MCZ are labelled “Santo Tomás, Península de Zapata, Cuba”, one in AMNH “Ciénaga de Zapata, Cuba”. POPULATION At least four birds were collected in 1927 (specimens in MCZ) and Bond (1971) had no difficulty in finding the species in 1931, when two birds were collected and others seen and heard. -

A Tool Kit for Media in the OECS

Keeping Biodiversity Issues in the News A Tool Kit for Media in the OECS Keeping Biodiversity in the News: A Tool Kit for Media in the OECS Keeping Biodiversity Issues in the News A Tool Kit for Media in the OECS Keeping Biodiversity in the News: A Tool Kit for Media in the OECS Cover Photo Credits: Peter Espeut, Greg Pereira and Tecla Fontenard Copyright © 2011 Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States Published by the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) Environment and Sustainable Development Unit (ESDU) The OECS Secretariat Morne Fortune P.O. Box 179 Castries Saint Lucia Telephone: (754) 452 2537 Fax: (754) 453 1628 Email: [email protected] Website: www.oecs.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS). Keeping Biodiversity in the News: A Tool Kit for Media in the OECS i FOREWARD By Keith Nichols Head of the Environmental Sustainable Development Unit (ESDU) Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) ` Few people in the Caribbean region are aware that we live in one of the world’s most important “biodiversity hot spots”. The entire Caribbean region is recognized as the world’s fifth most critical bio- diversity hot spot – which means that many of the unique plants and animals that exist only in our region – and no where else – are under serious threat of extinction unless strong action is taken to protect them now. -

Nuevas Localidades Para La Gallinuela De Santo Tomás Cyanolimnas Cerverai Y La Ferminia Ferminia Cerverai, En La Ciénaga De Zapata, Cuba

Nuevas localidades para la Gallinuela de Santo Tomás Cyanolimnas cerverai y la Ferminia Ferminia cerverai, en la Ciénaga de Zapata, Cuba Arturo Kirkconnell, Osmany González, Emilio Alfaro y Lázaro Cotayo Cotinga 12 (1999): 57–60 The first official observation during the last 20 years is recorded for Zapata Rail Cyanolimnas cerverai. Two new localities for the rail and three new for Zapata Wren Ferminia cerverai were found during fieldwork in November and December 1998. Totals of 17 rails and 24 wrens were recorded. In an area of 230 ha, we estimated there to be 70–90 rails. A list of all birds observed in the rivers Hatiguanico and Guareira is also presented. Introducción La Ciénaga de Zapata, situada a unos 160 km al sureste de la Ciudad de la Habana, representa el área de mayor diversidad de aves de la Isla de Cuba (202 especies, Kirkconnell, datos sin publicar). De las mismas, un total de 20 endémicos se encuentran en dicha región. Dos de los mismos fueron objeto de estudio durante las dos primeras expediciones llevadas a cabo en el período comprendido entre el 13 y el 19 de noviembre y del 14 al 21 de diciembre de 1998. Las especies focales fueron la Gallinuela de Santo Tomás Cyanolimnas cerverai y la Ferminia Ferminia cerverai, descubiertas por Fermín Cervera en los años 1926 y 1927, en la localidad de Santo Tomás. Dichas especies presentan una distribución muy restringida, las dos exclusivas de las áreas cenagosas con herbazales de la Ciénaga de Zapata (181,983 ha). Ambas se les considera dentro de la categoría en peligro2. -

Schnaitman, Rachel.Pdf

A REVIEW OF THREATS TO ISLAND ENDEMIC RAILS by Rachel Schnaitman A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Wildlife Conservation with Distinction. Spring 2010 Copyright 2010 Rachel Schnaitman All Rights Reserved A REVIEW OF THREATS TO ISLAND ENDEMIC RAILS by Rachel Schnaitman Approved:______________________________________________________________ W.Gregory Shriver, Ph.D. Professor in charge of the thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved:______________________________________________________________ Jacob L. Bowman, Ph.D. Committee member from the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Approved: _____________________________________________________________ K. Kniel, Ph.D. Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved:_____________________________________________________________ Ismat Shah, Ph.D. Chair of the University Committee on Student and Faculty Honors ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the Undergraduate Research Program for allowing me to be involved with the research program. I would also like to thank my advisor, Dr. Greg Shriver for supporting me and guiding me through this process. Furthermore I would like to thank my committee, Dr. J. Bowman and Dr. K. Kniel. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................... -

CUBA: the COMPLETE TOUR Petri Hottola (University of Oulu, Finland & Finnish University Network for Tourism Studies)

BIRD TOURISM REPORTS 1/2014 CUBA: THE COMPLETE TOUR Petri Hottola (University of Oulu, Finland & Finnish University Network for Tourism Studies) Cuba, the largest island of Greater Antilles, has recently become the favorite tourism destination in the Caribbean. One of the main attractions of the island has been a political one, a chance to see a socialist state, a rarity in today’s world. In addition, comfortable climate, various cultural features and, for nature- lovers, high degree of avian endemism have at times made it difficult to find vacant seats to Cuba during the high season, in the middle of northern hemisphere winter. In winter 2013-2014, I finally managed to visit the island for nine days, between 19th and 28th December. The journey was the classical circular tour, designed to maximize one’s chances to see the special birds of Cuba: from Havana to Pinar del Rio, from there to Zapata Swamp, from Zapata to Sierra de Najasa in the east, northwest to Cayo Coco, back to Zapata Swamp and finally, again to Havana. Fig. 1. Welcome to Cuba! (A Cuban Screech Owl peaks out of her home at Zapata Swamp). In regard to timing, mid-winter appeared to be an ideal time to find the endemic bird species. The migratory Cuban Martins may not be there, but for example at Zapata Swamp, the accessibility was excellent and all my target species were available. Till November, some parts of Soplillar, for example, may well be too wet to be accessed. In December, it was sunshine and moderate to no wind throughout the visit, with short periods of rain on a single afternoon, while driving between Cayo Coco and Playa Larga.