Communicating Conservation Are Zoos Learning from Their Visitors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Zoo New England Reciprocal List

2019 Zoo New England Reciprocal List State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone Number CANADA Calgary - Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Stephenie Motyka 403-232-9312 Quebec – Granby Granby Zoo 50% Mireille Forand 450-372-9113 x2103 Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 416-392-9103 MEXICO Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon 50% David Rocha 52-477-210-2335 x102 Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Patty Pendleton 205-879-0409 x232 Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Shannon Wolf 907-224-6355 Every year, Zoo New England Arizona Phoenix The Phoenix Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 602-914-4365 participates in a reciprocal admission Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Membership Dept. 877-526-3960 program, which allows ZNE members Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 520-881-4753 free or discounted admission to other Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Kelli Enz 501-661-7218 zoos and aquariums with a valid California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 50% Becky Maxwell 805-461-5080 x2105 membership card. Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 50% Kathleen Juliano 707-441-4263 Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Katharine Alexander 559-498-5938 Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 323-644-4759 Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Sue Williams 510-632-9525 x150 This list is amended specifically for Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Elisa Escobar 760-346-5694 x2111 ZNE members. If you are a member Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Brenda Gonzalez 916-808-5888 of another institution and you wish to San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Jaz Cariola 415-623-5331 visit Franklin Park Zoo or Stone Zoo, San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% Nicole Silvestri 415-753-7097 please refer to your institution's San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo 50% Snthony Teschera 408-794-6444 reciprocal list. -

February 2020 Volume 23, Issue 1

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 23, ISSUE 1 PUBLISHED FOR FRIENDS OF ROGER WILLIAMS PARK ZOO wElCoMe! By Jeremy Goodman, DVM Executive Director, RWP Zoo and RI Zoological Society In November our Zoo family lost its matriarch, Mrs. Sophie Danforth. Sophie founded the Rhode Island Zoological Society, the not-for- profit organization that manages the Zoo, in 1962. When Sophie first came to the Zoo, the animals were spread throughout the park and were housed in what she emphatically stated were “deplorable conditions”. She not only contributed money to improve the infrastructure of the Zoo, but ran a gift shop and sold Zoo memberships to help provide food and care for the animals. She worked with politicians to secure funding and travelled the world to visit other zoos and bring back best practices. Sophie joined the American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums (now the AZA) and befriended some of the world’s greatest conservationists such as Gerald Durrell and William Conway. Because of her, we have become the international conservation organization we are today. It is not an understatement to say that the incredible Zoo that we now have is because of her hard work and vision. When asked how she did it, she said “Well, I had common sense and a love for animals.” Mrs. Sophie Danforth is an inspiration teaching us to make a lasting impact for the betterment of the world. Sophie Danforth will be missed by all of us. I look forward to seeing you at the Zoo! 1 2 Griffy It’s 8:00 AM on a cold December morning. -

Reversing America's Wildlife Crisis

ReveRsing AmeRicA’s WILDLIFE CRISIS SECURING THE FUTURE OF OUR FISH AND WILDLIFE MARCH 2018 REVERSING AMERICA’s Wildlife CRISIS 1 ReveRsing AmeRicA’s Wildlife cRisis SECURING THE FUTURE OF OUR FISH AND WILDLIFE Copyright © 2018 National Wildlife Federation Lead Authors: Bruce A. Stein, Naomi Edelson, Lauren Anderson, John J. Kanter, and Jodi Stemler. Suggested citation: Stein, B. A., N. Edelson, L. Anderson, J. Kanter, and J. Stemler. 2018. Reversing America’s Wildlife Crisis: Securing the Future of Our Fish and Wildlife. Washington, DC: National Wildlife Federation. Acknowledgments: This report is a collaboration among National Wildlife Federation (NWF), American Fisheries Society (AFS), and The Wildlife Society (TWS). The authors would like to thank the many individuals from these organizations that contributed to this report: Taran Catania, Kathleen Collins, Patty Glick, Lacey McCormick, and David Mizejewski from NWF; Douglas Austen, Thomas Bigford, Dan Cassidy, Steve McMullin, Mark Porath, Martha Wilson, and Drue Winters from AFS; and John E. McDonald, Jr., Darren Miller, Keith Norris, Bruce Thompson, and Gary White from TWS. We are especially grateful to Maja Smith of MajaDesign, Inc. for report design and production. Cover image: Swift fox (Vulpes macrotis), North America’s smallest wild canid, has disappeared from about 60 percent of its historic Great Plains range. Once a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act, collaborative state and federal conservation efforts have stabilized the species across much of its remaining range. Photo: Rob Palmer Reversing America’s Wildlife Crisis is available online at: www.nwf.org/ReversingWildlifeCrisis National Wildlife Federation 1200 G Street, NW, Suite 900 Washington, D.C. -

Endangered Species Bulletin, Vol 27 No. 1

REGIONAL NEWS & RECOVERY UPDATES Region 4 Spring Creek Bladderpod (Lesquerella perforata) The FWS Cookeville, Tennessee, Field Office, state of Tennessee, and city of Leba non have signed a cooperative management agree ment for the protection of a Spring Creek bladderpod population occurring on property re cently acquired by the city. The city purchased approximately 3.5 acres (1.4 hectares) adjacent to a road construction project for the perpetual Regional endangered species staffers have protection of Spring Creek bladderpods occurring reported the following news: on the property. This site is one of only 17 known locations harboring this endangered species and American burying beetle Region 1 is the first to receive this level of protection. Photo by Andrea Kozol By providing for the perpetual protection of this This effort is probably one of the largest reintro species while allowing for the road construction, ductions ever undertaken for an endangered in- this agreement represents a cooperative approach sect species. to resolving issues between development and habi tat protection. We have been able to secure simi Present to document the work was a film crew lar management agreements for the Spring Creek from the TV program, Wild Moments, and the bladderpod with two Lebanon-based corporations, Providence Journal newspaper. Partners in the Cracker Barrel Old Country Store, Inc., and TRW work include the Rhode Island Division of Fisher Automotive. All 17 occurrences of this plant are ies and Wildlife, Massachusetts Division of Fisher located on private property and efforts are under- ies and Wildlife, Roger Williams Park Zoo, Massa way to encourage the other landowners to follow chusetts Audubon Society, University of Massa the city’s lead. -

2009 Conservation Impact Report

2009 Conservation Impact Report Introduction AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums serve as conservation centers that are concerned about ecosystem health, take responsibility for species survival, contribute to research, conservation, and education, and provide society the opportunity to develop personal connections with the animals in their care. Whether breeding and re-introducing endangered species, rescuing and rehabilitating sick and injured animals, maintaining far-reaching educational and outreach programs or supporting and conducting in-situ and ex-situ research and field conservation projects, zoos and aquariums play a vital role in maintaining our planet’s diverse wildlife and natural habitats while engaging the public to appreciate and participate in conservation. In 2009, 127 of AZA’s 238 accredited institutions and certified-related facilities contributed data for the 2009 Conservation Impact Report. A summary of the 1,762 conservation efforts these institutions participated in within ~60 countries is provided. In addition, a list of individual projects is broken out by state and zoological institution. This report was compiled by Shelly Grow (AZA Conservation Biologist) as well as Jamie Shockley and Katherine Zdilla (AZA Volunteer Interns). This report, along with those from previous years, is available on the AZA Web site at: http://www.aza.org/annual-report-on-conservation-and-science/. 2009 AZA Conservation Projects Grevy's Zebra Trust ARGENTINA National/International Conservation Support CANADA Temaiken Foundation Health -

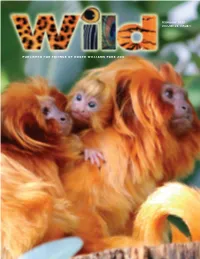

2019 Spring Wild Magazine.Pdf

APRIL 2019 VOLUME 22, ISSUE 2 PUBLISHED FOR FRIENDS OF ROGER WILLIAMS PARK ZOO wElCoMe! By Jeremy Goodman, DVM Executive Director, RWP Zoo and RI Zoological Society Spring at the Zoo is a magical time. As the last of the winter’s snow melts away and the flowers begin to bloom, the Zoo breathes new life. Whether it is a new baby animal or the first Del’s lemonade of the season, a trip to Roger Williams Park Zoo this time of year is special. While you are visiting make sure to stop by our World of Adaptations to see our river otter triplets born in March 2018. Much like they would do in the wild once old enough, our pups are set to leave mom and dad this Spring and start families of their own. As part of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ North American River Otter species survival plan, our three youngsters will be making new homes throughout the country and ensuring a thriving otter population through this cooperative breeding effort. River otters are one of over 30 species housed at our Zoo that are managed collectively in North America to ensure their long-term survival. Together with other AZA zoos we participate in the Saving Animals from Extinction program – known as SAFE. I know that together and with your help we will ensure all future generations can forever enjoy wildlife and wild places. I look forward to seeing you at the Zoo! members corner Download your digital eMembership Card on the App Store or Play Store for fast and easy access. -

CONNECT FEATURES September 2014 10 FOUNDATIONS of the FUTURE the Value of In-Person Training in a Digital World Jane Ballentine

CONNECT FEATURES September 2014 10 FOUNDATIONS OF THE FUTURE The Value of In-Person Training in a Digital World JANE BALLENTINE 14 ORGANIZATIONAL MANAGEMENT An Essential Piece of the Organizational Puzzle JENNY YEE GREBE, CVA AND DAN RADLEY 18 VOLUNTEERS AND FIELD CONSERVATION ISABEL SANCHEZ AND JEAN GALVIN 22 THE IMPACT OF AZA VOLUNTEERS SEAN D. DEVEREAUX 25 TO BE OR NOT TO BE OUTSIDE Choice is Enriching for Apes STEVE ROSS, PHD 29 FOR SERVICE, AT YOUR SERVICE VMC Committee Update 47 IN MEMORIAM Mary Healy 48 THINK OUTSIDE THE BOX LAURA KLOPFER 54 INTERNSHIPS: AN INVESTMENT FOR THE FUTURE PAUL BISHOP AND RACHAEL ROBINSON 59 Volunteer Blood COLLECTION from NILE Hippopotamus MARK HACKER IN EVERY ISSUE 3 A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD 6 CONSERVATION & RESEARCH 32 MEMBER NEWS 32 GREEN TALES 40 A MESSAGE FROM THE THE PRESIDENT & CEO ON THE COVER 41 BIRTHS & HATCHINGS The value of AZA Professional Development courses extends to accredited members of 50 CONSERVATION SPOTLIGHT all sizes. Looking at course attendance numbers since 2007, it clear that the largest AZA member institutions (by budget size) had higher total attendance at AZA courses, but 52 EXHIBITS smaller and mid-size institutions were also well-represented. “Kudus” to all the instruc- 60 announcements tors and students who have participated and have made the courses such a success. 62 MEMBER UPDATES GREATER KUDU @ STEPHANIE ADAMS, HOUSTON ZOO 65 INDEX OF ADVERTISERS 66 CALENDAR MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD reetings AZA members and stakeholders, chair of the board It is hard to believe that my year as Chair of our AZA Board is coming to an end. -

The WAZA Decade Project | P 2 Sexual Coral Reproduction | P 7 WAZA Annual Report 2012 | Insert – the Lost Chambers

May 2/13 2013 The WAZA Decade Project | p 2 Sexual Coral Reproduction | p 7 WAZA Annual Report 2012 | insert – The Lost Chambers. | © Pio De Rose The Lost – Atlantis The Palm Atlantis WAZA news 2/13 Gerald Dick Contents Editorial Dear WAZA members and friends! WAZA Biodiversity Decade Project ...........................2 This edition of WAZA News is a very Aquaria, the Blue Glass special one. With the support of WAZA’s Landscape ...................................3 aquarium committee chair and past International Aquarium president, Dr Mark Penning and Paul Congress .....................................4 Boyle of AZA, we have designed a focus Review of Japanese on aquariums and water related issues. Aquariums ..................................5 As the interest was overwhelmingly Sexual Coral Reproduction great some of the submitted articles & Reef Conservation ...................7 have to be postponed for publishing Unity, Strength & Synergy .........9 in a later edition of the WAZA News. WAZA Interview: Nicely coinciding with this focus are Dennis Ethier ............................ 12 some decisions which were taken at this Impact year’s CITES CoP16 and are related to of Superstorm Sandy ................ 14 listings of shark species. My Career: David Kimmel ......... 17 With this edition of WAZA News we are Whale Sharks ............................19 also starting a series about the WAZA Book Reviews ...........................22 Decade project, which has taken off the Announcements ....................... 23 ground enormously well. Throughout Tarpons, Ladyfishes the year you will be informed about the & Bonefishes .............................24 developments until the planned launch Highlights during the WAZA marketing conference of CITES CoP 16 ........................25 in May 2014. © WAZA CITES in Action: UWEC ............. 27 Included here is also a generous offer for Gerald Dick and whale shark at aqua planet, Jeju. -

Measuring the Success of the Endangered Species Act: Recovery Trends in the Northeastern United States

MEASURING THE OF THE ENDANGEREDSuccess SPECIES ACT Recovery Trends in the Northeastern United States Measuring the Success of the Endangered Species Act: Recovery Trends in the Northeastern United States A Report by the Center for Biological Diversity © February 2006 Author: Kieran Suckling, Policy Director: [email protected], 520.623.5252 ext. 305 Research Assistants Stephanie Jentsch, M.S. Esa Crumb Rhiwena Slack and our acknowledgements to the many federal, state, university and NGO scientists who provided population census data. The Center for Biological Diversity is a nonprofit conservation organization with more than 18,000 members dedicated to the protection of endangered species and their habitat through science, policy, education and law. CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY P.O. Box 710 Tucson, AZ 85710-0710 520.623.5252 www.biologicaldiversity.org Cover photo: American peregrine falcon Photo by Craig Koppie Cover design: Julie Miller Table of Contents Executive Summary…………………………………………………………….. 1 Methods………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Results and Discussion………………….………………………………………. 5 Photos and Population Trend Graphs…………………………...……………. 9 Highlighted Species..……………………………………………………...…… 32 humpback whale, bald eagle, American peregrine falcon, Atlantic piping plover, shortnose sturgeon, Atlantic green sea turtle, Karner blue butterfly, American burying beetle, seabeach amaranth, dwarf cinquefoil Species Lists by State………………………………………………………….. 43 Technical Species Accounts………………………………………………….... 49 Measuring the Success of the Endangered Species Act Executive Summary The Endangered Species Act is America’s foremost biodiversity conservation law. Its purpose is to prevent the extinction of America’s most imperiled plants and animals, increase their numbers, and effect their full recovery and removal from the endangered list. Currently 1,312 species in the United States are entrusted to its protection. -

2016 Wildcare Institute Annual Report

WildCare Institute 2016 Annual Report WildCare At A Glance Center for American Burying Beetle Conservation Center for Conservation in Madagascar • Saving this important insect helps the ecosystem because this insect removes • Supporting the international consortium, Madagascar Fauna and Flora Group, dead and decaying animals naturally based at the Saint Louis Zoo—a founding member in 1988 • Reintroducing Zoo-born beetles to the wild—a first for an endangered • Conserving biodiversity through research, education and capacity building species in Missouri • Studying the health and genetics of endangered lemurs and endemic • Researching beetle genetics and breeding helps species recovery carnivore communities Center for Avian Conservation in the Pacific Islands Center for Native Pollinator Conservation • Working to save Pacific Island bird species since 1994 • Planting dozens of miles of pollinator habitats along roadsides with support from • Building assurance populations to prevent island birds from disappearing multiple Missouri state agencies • Transferring “seed” bird populations to neighboring snake-free sanctuary islands • Founding Missourians for Monarchs to develop a state-wide conservation plan for for successful breeding monarch butterflies and native pollinators • Continuing to establish populations in human care to support wild populations • Increasing monarch butterfly habitat by encouraging planting of multiple community pollinator gardens Center for Avian Health in the Galápagos Islands • Spearheading honey bee/pollinator -

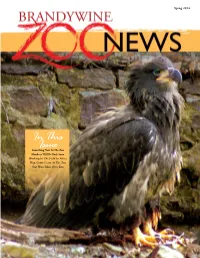

In This Issue Spring 2013

Sprng 2014 Something New At The Zoo Monkeys Will Be Back Soon Working In The Field In Africa Play, Grow, Learn At The Zoo Star Wars Takes Over Zoo In This Issue Spring 2013 IN THIS ISSUE On the Cover Partying With A Purpose . 3 Our cover features someone new here Something New At The Zoo . 4 at the zoo. She’s a juvenile Bald Eagle Monkeys Will Be Back Soon . 5 (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) who came to Meet Donna Evernham . .5 us from a rehabilitation facility. She was Enrichment and Training . 6-7 permanently injured when she was blown Our Commitment To Conservation .8 out of her nest in western Pennsylvania in a violent storm. As a result, she cannot Kid’s Corner . 9 Something New At The Zoo Monkeys Will Be Back Soon Working In The Field In Africa fly and is unable to survive on her own in Play, Grow, Learn At The Zoo Working In The Field In Africa . 10-11 Star Waqars Takes Over Zoo the wild. We are pleased to be able to pro- Family Programs . 12-13 In This Play, Grow, Learn At The Zoo . 14 vide her a new home at the Brandywine Zoo Issue where she can receive excellent care from our Star Wars Takes Over Zoo . .15 animal keepers. Our members and visitors will New Year & Volunteer Program 16-17 have the unique opportunity to watch her grow AAZK . .18 into adulthood and take on the distinctive white Reciprocal Zoos & Aquariums . 19 plumage on her head and tail that will identify her as our national symbol. -

Go Ask Parents Mcdonald's - Dedham - "It Has a Children's Museum Great Outdoor Play Space"

Go Ask Parents McDonald's - Dedham - "It has a Children's Museum great outdoor play space". 9 Sullivan Avenue (In Easton) Borderland State Park - Sharon P.O. Box 417 Dear Readers, Crescent Ridge Dairy - Sharon - No. Easton, MA 02356 "Cow's are grazing now." (508) 230-3789 This spring we sent out surveys Ames Street Playground - Sharon - "It Franklin Park Zoo to some of our parents and providers has big shade trees." asking them for their ideas on what Pony rides at the Lazy Ranch - Franklin Park they like to do with their children Randolph Street - $2.00 Boston, MA 02021 when warm weather hits. In the Peaceful Meadows Dairy - Route 18 (617) 442-0991 survey, we asked our experts to list Whitman - "Kids can go in the Drumlin Farms some of their favorite places that are barn and see the cows." Drumlin Farms close to home and don't cost a lot of Fishing at the Reservoir - Pleasant Lincoln, MA 01773 money. We also requested vacation Street, Canton (617) 259-9005 tips that make vacations away stress 4-H Farm - Walpole free for grown-ups and children. We Puppet Showplace Theatre Cunningham Park - Milton sought out activities that could be Pequitside Farm - Canton - Play- 32 Station Street done in the backyard and for rainy ground, open field for kite flying Brookline Village days, activities for indoors, as well. Bliss Dairy - Attleboro (617) 731-6400 We then compiled all of their ideas, Big Apple Farm - Wrentham added a few of our own and included Wheelock Family Theatre Walpole Mall - Pet Store them in this newsletter.