Speaks for Itself, This One Does

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

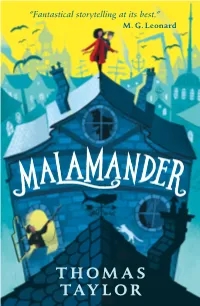

Malamander-Extract.Pdf

“Fantastical storytelling at its best.” M. G. Leonard THOMAS TAYLOR THOMAS TAYLOR This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or, if real, used fictitiously. All statements, activities, stunts, descriptions, information and material of any other kind contained herein are included for entertainment purposes only and should not be relied on for accuracy or replicated as they may result in injury. First published 2019 by Walker Books Ltd 87 Vauxhall Walk, London SE11 5HJ 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 Text and interior illustrations © 2019 Thomas Taylor Cover illustrations © 2019 George Ermos The right of Thomas Taylor to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This book has been typeset in Stempel Schneider Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, taping and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-4063-8628-8 (Trade) ISBN 978-1-4063-9302-6 (Export) ISBN 978-1-4063-9303-3 (Exclusive) www.walker.co.uk Eerie-on-Sea YOU’VE PROBABLY BEEN TO EERIE-ON-SEA, without ever knowing it. When you came, it would have been summer. -

Since I Began Reading the Work of Steve Ditko I Wanted to Have a Checklist So I Could Catalogue the Books I Had Read but Most Im

Since I began reading the work of Steve Ditko I wanted to have a checklist so I could catalogue the books I had read but most importantly see what other original works by the illustrator I can find and enjoy. With the help of Brian Franczak’s vast Steve Ditko compendium, Ditko-fever.com, I compiled the following check-list that could be shared, printed, built-on and probably corrected so that the fan’s, whom his work means the most, can have a simple quick reference where they can quickly build their reading list and knowledge of the artist. It has deliberately been simplified with no cover art and information to the contents of the issue. It was my intension with this check-list to be used in accompaniment with ditko-fever.com so more information on each publication can be sought when needed or if you get curious! The checklist only contains the issues where original art is first seen and printed. No reprints, no messing about. All issues in the check-list are original and contain original Steve Ditko illustrations! Although Steve Ditko did many interviews and responded in letters to many fanzines these were not included because the checklist is on the art (or illustration) of Steve Ditko not his responses to it. I hope you get some use out of this check-list! If you think I have missed anything out, made an error, or should consider adding something visit then email me at ditkocultist.com One more thing… share this, and spread the art of Steve Ditko! Regards, R.S. -

Title FX Volume 2

Title FX Vol. 2 Title fx vol 2 Disc Track Index Secs Description Filename Category TFX2-01 1 1 7.4 Digital Pulse Alarm Scan Warning DigitalPulseAlarmSc TFX2001 Computers & Beeps TFX2-01 2 1 4.1 Low Heavy Text Materialize Sweep LowHvyTextMateriali TFX2002 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 3 1 3.3 Heavy Text Sliding Into Shifted Rumble Short HvyTextSlidingShift TFX2003 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 4 1 4.1 Sliding Pitch Motor By SlidingPitchMotorBy TFX2004 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 5 1 6.9 Slide Multi Whoosh Phase Pitch Looped SlideMultiWhooshPha TFX2005 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 6 1 6.5 Slide Pitch Looped Sci-Fi Motorcycles SlidePitchLoopedSci TFX2006 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 7 1 6.1 Slide Pitch Looped Sci-Fi Motorcycle Slow Pitch SlidePitchLoopedSci TFX2007 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 8 1 1.4 Low Rumble Transition LowRumbleTransition TFX2008 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 9 1 2.5 Fast Text Fade Into Low Rumble Transition FstTextFadeLowRumbl TFX2009 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 10 1 2.6 Warp Tone Modulated Fade In WarpToneModulatedFa TFX2010 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 11 1 5.9 Future Mechanical Slow By FutureMechanicalSlw TFX2011 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 12 1 2.7 Heavy Mechanical Fly Transitional By Short HvyMechanicalFlyTra TFX2012 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 13 1 2.6 Mechanical Fly By Whoosh MechanicalFlyByWhoo TFX2013 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 14 1 4.1 Mechanical Fly By Modulated Slow Pitch Descending Transition MechanicalFlyByModu TFX2014 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 15 1 7.2 Mechanical Fly By Modulated -

“The Rook” Information Guide

The Return of “The Rook” Information Guide There is a clear void in today’s American pop culture that is The Rook. It all began in the early 1960’s. Bill, or his adventure hero alter-identity “Billy De” began working in comics before he grew his first whisker. His fascination with comic books was shared by his partner in crime Marty Arbunich. Together they created some of the very first comic book fanzines; Fantasy Hero, Fantasy Illustrated, Yancy Street Journal and Voice of Comicdom, starting at the ripe age of 14. Bill and Marty worked tirelessly to meet self-imposed deadlines as if their loyal fans relied on their publications. On one occasion Bill even snuck into Sacred Heart High School’s art room and used the Dot printer to mass produce their fanzine. Before Comic Con became the premier pop-culture comic event, there was the World Science Fiction Convention (now known as WorldCon) and in 1964 it was in Oakland. Although only 523 were in attendance, this show would have resounding impacts on Bill’s career in comics. Also in attendance was maybe the greatest science fiction fan of all time Forrest J. Ackerman, who contributed to the first science fiction fanzine, The Time Traveler. In the same year, The Time Travelers, a science fiction film, would go into production. The cast included Forry Ackerman. The Rook’s return to comics is nearly 50 years to the date of the event that would inspire Bill’s creative direction. Forrest Ackerman would later go on to create the highly popular alternative comic character Vampirella in 1969. -

“I Am an Other and I Always Was…”

Hugvísindasvið “I am an other and I always was…” On the Weird and Eerie in Contemporary and Digital Cultures Ritgerð til MA-prófs í menningafræði Bob Cluness May 2019 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindad Menningarfræði “I am an other and I always was…” On the Weird and Eerie in Contemporary and Digital Cultures Ritgerð til MA-prófs í menningafræði Bob Cluness Kt.: 150676-2829 Tutor: Björn Þór Vilhjálmsson May 2019 Abstract Society today is undergoing a series of processes and changes that can be only be described as weird. From the apocalyptic resonance of climate change and the drive to implement increasing powerful technologies into everyday life, to the hyperreality of a political and media landscape beset by chaos, there is the uneasy feeling that society, culture, and even consensual reality is beginning to experience signs of disintegration. What was considered the insanity of the margins is now experienced in the mainstream, and there is a growing feeling of wrongness, that the previous presumptions of the self, other, reality and knowledge are becoming untenable. This thesis undertakes a detailed examination of the weird and eerie as both an aesthetic register and as a critical tool in analysing the relationship between individuals and an impersonal modern society, where agency and intention is not solely the preserve of the human and there is a feeling not so much of being to act, and being acted upon. Using the definitions and characteristics of the weird and eerie provided by Mark Fisher’s critical text, The Weird and the Eerie, I set the weird and eerie in a historical context specifically regarding both the gothic, weird fiction and with the uncanny, I then analyse the presence of the weird and the eerie present in two cultural phenomena, the online phenomenon of the Slender Man, and J.G. -

Untitled Approximate Original Scheduled (Eight Pages) On-Sale Date: July 11, 1978

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Acknowledgements ....................................................... 5 Prologue. 7 DC Comics’ Lineup of Titles: Early 1976 ................................................ 10 Part 1: Pre-Explosion (1976-1978) ........................................................ 11 Interlude: Ring Out the Old, Ring In the New ............................................ 23 DC Comics’ Lineup of Titles: Early 1977 ................................................ 31 DC Comics’ Lineup of Titles: Early 1978 (Pre-DC Explosion) .............................. 52 Part 2: Explosion (1978) ................................................................. 53 DC Comics’ Lineup of Titles: June, July and August 1978 (The DC Explosion) ............... 66 DC Comics’ Lineup of Titles: June, July and August 1978 (Unpublished) .................... 66 Part 3: Implosion (1978-1980) ............................................................ 67 DC Comics’ Lineup of Titles: Early 1979 (Post-DC Implosion) ............................. 76 Bonus Gallery ....................................................................... 79 Interlude: Cancelled Comic Cavalcade: The Index ........................................ 90 Interlude: Whatever Happened to –? ................................................... 98 DC Comics’ Lineup of Titles: June, July and August 1980 ................................ 117 Cancellations by Month of Publication ................................................... 127 Afterword ........................................................................... -

The Starman Omnibus Vol. 2 PDF Book

THE STARMAN OMNIBUS VOL. 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Robinson | 416 pages | 11 Sep 2012 | DC Comics | 9781401221959 | English | New York, NY, United States The Starman Omnibus Vol. 2 PDF Book Martin Luther King Jr. Collects Starman 2nd Series and 1,,, Stars and S. It's stuck somewhere between a character-driven indie comic like Strangers In Paradise and a classic DC superhero comic. Fate, the Shade, and the Golden Age Sandman. In the pages of Starman we get a looser, more cartoony style from Harris, but with hint at the refined style he currently draws in. This made me realize that I am not a huge fan of Tony Harris's art. All rights reserved. Zero Hour: Crisis in Time 25th Anniversary. However, he got stranded on Earth, the Kingdom Come universe, thus witnessing the dramatic events on that Earth and receiving added damage to his frail mind, worsened by the lack of the advanced medication to which he had had access in his own time. Of course there is his wise mentor in his father, Ted. Books by James Robinson. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Creepy Eerie. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Much like Opal City itself, Robinson crafts a fantastic blend of old and new in his story. He pickpocketed a pistol and fired on the group. An old guy now, but his thought process is shown here, and his arc striked curiosity inside of me: now I want to know more about the character, and how he was when younger This book gave me a bunch of mixed feelings. -

Marvel Catalog 2020

TERRY’S COMICS Welcome to Catalog number twenty-three. Thank you to everyone who ordered from one or more of our previous catalogs and especially Gold and Platinum customers. Please be patient when you call if we are not here, we promise to get back to you as soon as possible. Our normal hours are Monday through Friday 8:00AM-4:00PM Pacific Time. You can always send e-mail requests and we will reply as soon as we are able. All comics that are stickered below $10 have been omitted as well as paperbacks, Digests, Posters and Artwork and Magazines. I also removed the mid-grade/priced issue if there were more than two copies, if you don't see a middle grade of an issue number, just ask for it. They are available on the regular web-site www.terryscomics.com. If you are looking for non-key comics from the 1980's to present, please send us your want list as we have most every issue from the past 35 years in our warehouse. Over the past years we have purchased several nice collections. One of the more interesting collections were the British Collection from a Dealer in England, it included a near full Pre-code Horror/Sci-Fi selection, we purchased it with Jamie Newbold of SoCal Comics. The other was a very nice group of mostly DC Gold/Silver age comics that had many the Keys in above average condition, we purchased this collection with Ken Hunt of the Bunky Brothers. We also finally finished purchasing the Jerome Wenker Collection. -

Marvel January – April 2021

MARVEL Aero Vol. 2 The Mystery of Madame Huang Zhou Liefen, Keng Summary THE MADAME OF MYSTERY AND MENACE! LEI LING finally faces MADAME HUANG! But who is Huang, and will her experience and power stop AERO in her tracks? And will Aero be able to crack the mystery of the crystal jade towers and creatures infiltrating Shanghai before they take over the city? COLLECTING: AERO (2019) 7-12 Marvel 9781302919450 Pub Date: 1/5/21 On Sale Date: 1/5/21 $17.99 USD/$22.99 CAD Paperback 136 Pages Carton Qty: 40 Ages 13 And Up, Grades 8 to 17 Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes CGN004080 Captain America: Sam Wilson - The Complete Collection Vol. 2 Nick Spencer, Daniel Acuña, Angel Unzueta, Paul Re... Summary Sam Wilson takes flight as the soaring Sentinel of Liberty - Captain America! Handed the shield by Steve Rogers himself, the former Falcon is joined by new partner Nomad to tackle threats including the fearsome Scarecrow, Batroc and Baron Zemo's newly ascendant Hydra! But stepping into Steve's boots isn't easy -and Sam soon finds himself on the outs with both his old friend and S.H.I.E.L.D.! Plus, the Sons of the Serpent, Doctor Malus -and the all-new Falcon! And a team-up with Spider-Man and the Inhumans! The headline- making Sam Wilson is a Captain America for today! COLLECTING: CAPTAIN AMERICA (2012) 25, ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA: FEAR HIM (2015) 1-4, ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA (2014) 1-6, AMAZING SPIDERMAN SPECIAL (2015) 1, INHUMAN SPECIAL (2015) 1, Marvel ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA SPECIAL (2015) 1, CAPTAIN AMERICA: SAM WILSON (2015) 1-6 9781302922979 Pub Date: 1/5/21 On Sale Date: 1/5/21 $39.99 USD/$49.99 CAD Paperback 504 Pages Carton Qty: 40 Ages 13 And Up, Grades 8 to 17 Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes CGN004080 Marvel January to April 2021 - Page 1 MARVEL Guardians of the Galaxy by Donny Cates Donny Cates, Al Ewing, Tini Howard, Zac Thompson, .. -

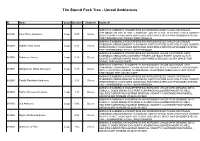

Unreal Ambiences

The Sound Pack Tree - Unreal Ambiences ID Name Loop Duration Channels Keywords AMBIANCE AMBIENCE ATMOSPHERE BACKGROUND BUZZ CHAOS CONTINUUM DIMENSION DREAM ENERGY FLASHBACK FORTH FUTURE GLITCH GLITCHES INSANITY 082100 Time Travel Ambience Loop 0:27 Stereo INTERFERENCE NIGHTMARE OVERLOAD PAST SPACE SPACESHIP SWOOSH SYSTEM TIME TRANSMISSION TRAVEL WARP WHOOSH AMBIANCE AMBIENCE ATMOSPHERE BACKGROUND BUZZ CHAOS CONTINUUM DIMENSION DREAM ENERGY FLASHBACK FORTH FUTURE GLITCH GLITCHES INSANITY 082200 Digital Chaos Storm Loop 0:15 Stereo INTERFERENCE NIGHTMARE OVERLOAD PAST SPACE SPACESHIP SWOOSH SYSTEM TIME TRANSMISSION TRAVEL WARP WHOOSH AMBIANCE AMBIENCE ATMOSPHERE BACKGROUND CHAOS CONTINUUM DARK DIMENSION DREAM DRUGS ENERGY FEAR FLASHBACK FORTH GHOST GLITCH 082400 Nightmare Voices Loop 0:26 Stereo HAUNTED HORROR INSANE MAGIC NIGHTMARE OVERLOAD SCARY SPACE TIME TRAVEL TRIP VOICES WARP AMBIANCE AMBIENCE ATMOSPHERE BACKGROUND CHAOS CONTINUUM DARK DIMENSION DISHARMONIC DREAM DRUGS ENERGY FEAR FLASHBACK FORTH GHOST 082800 Disharmonic Ghost Orchestra Loop 0:18 Stereo GLITCH HAUNTED HORROR INSANE MAGIC NIGHTMARE OVERLOAD SCARY SPACE TIME TRAVEL TRIP VOICES WARP AMBIANCE AMBIENCE ATMOSPHERE BACKGROUND BUZZ CHAOS CONTINUUM DIMENSION DREAM ENERGY FLASHBACK FORTH FUTURE GLITCH GLITCHES INSANITY 082900 Painful Flashback Ambience . 1:11 Stereo INTERFERENCE NIGHTMARE OVERLOAD PAST SPACE SPACESHIP SWOOSH SYSTEM TIME TRANSMISSION TRAVEL WARP WHOOSH AMBIANCE AMBIENCE ATMOSPHERE BACKGROUND CHAOS DARK DEMONIC DEVIL DIABOLIC DOOM DREAM EVIL FEAR FLASHBACK HALLOWEEN