Using a Communication Perspective to Teach Relational Lawyering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Esther Perel

The Milton H. Erickson Foundation NEWSLETTER Vol. 28, No. 2 SUMMER 2008 SM Lesley College in Cambridge, Inside INTERVIEW Massachusetts (1982), and educa- tional psychology from the Hebrew This Issue University of Jerusalem (1979). Perel Esther Perel has been trained, supervised, and mentored among others, by Salvador CASE REPORT: By Marilia Baker, Phoenix Institute of Minuchin, MD at the Minuchin From Judith Gold’s memoir, Ericksonian Therapy Center for the Family in New York, My House on Stilts 4 Esther Perel is a multicultural, and mentions him as a dear family INTRODUCING THE INSTITUTES: multilingual Licensed Marriage and friend and cherished influence. She The Milton H. Erickson Institute Family Therapist in private practice also trained with Peggy Papp, MSW, Of Florianopolis, Brazil 5 in New York City. She is a world senior faculty and clinical supervisor renowned authority on couples sexu- of the Ackerman Institute for the CONTRIBUTOR OF NOTE: ality, cultural identity, cross-cultural Family. The Family Institute of Sofia Bauer, MD 6 relations, and interracial, interreli- Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the FACETS AND REFLECTIONS: gious marriages and committed Psychodrama Center of New York, That’s Right, Is It Not? A play about unions. Her therapeutic interests and N.Y. are among her other advanced the life of Milton H. Erickson, MD 8 clinical teachings center on multicul- training. She is a member of the turalism, eroticism, and sexuality American Family Therapy Academy MEETING REPORT: with a focus on both heterosexual and (AFTA) and of the Society for Sex Reflections: Celebrating Five same-sex couples. In addition, for Therapy and Research. -

Jock Mckeen Curriculum Vitae

June 6, 2013 Vita: John Herbert Ross McKeen PERSONAL: Name: John (Jock) Herbert Ross McKeen Address: 240 Davis Road, Gabriola Island, B.C. Canada V0R 1X1 Telephone: (250) 247-9211 Email: [email protected] Website: www.haven.ca Birthplace: Owen Sound, Ontario, Canada Birthdate: October 19, 1946 EDUCATION AND HONOURS: M.D. Degree University of Western Ontario 1970 Medical Internship Royal Columbian Hospital, New Westminster, B.C. Canada, 1970-71 Licentiate in College of Chinese Acupuncture Acupuncture Oxford, England 1974 (Lic.Ac.) Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) Vancouver Island University 2012 Honorary Degree CAREER: Television Panelist CFPL Television, London, Ontario 1962-65 Columnist London Free Press, London, Ontario 1963-64 Demonstrator Department of Anatomy University of Western Ontario 1965-66 Medical Research Department of Pharmacology, U.W.O. (Medical Research Council Grant) 1967 Intern C.A.M.S.I. Field Clinics Alexandria, Jamaica 1969 Intern Children's Psychiatric Research Institute, London, Ontario 1969-70 1 Intern Cedar Springs Institute Cedar Springs, Ontario 1968-70 Counsellor Alcoholism and Drug Addiction Research Foundation, London, Ontario 1969-70 Emergency Physician Burnaby General Hospital, Burnaby, B.C. 1971-74 Emergency Physician Royal Columbian Hospital New Westminster, B.C. 1971-74 Physician/Acupuncturist Private Practice, Vancouver, B.C. 1973-75 Co-Director Resident Fellow Program, Cold Mountain Institute, Cortes Island, B.C. 1975-80 Faculty Antioch College West, M.A. Program in Humanistic Psychology 1974-80 Program Director Cortes Centre for Human Development 1980-92 Senate Academy of Sciences for Traditional Chinese Medicine, Victoria, B.C. 1984-88 Advisory Board Hull Institute, Calgary, AB, Canada 1985-88 Board of Directors Cortes Centre for Human Development 1980-92 Board of Advisors Options for Children and Families Calgary, Alberta 1987-93 Board of Advisors Aitken Wreglesworth Architects, Ltd. -

Love & Intimacy

SYLLABUS LOVE & INTIMACY: THE COUPEES CONFERENCE JUNE 12 -14, 2003 Holiday hm Nob Hill San Francisco, California Ellyn Bader • Lonnie Barbach • David Geisinger Marty Klein • Pat Love • Cloe Madanes Bennet Wong &Jock McKeen • Peter Pearson Ayala Pines • Terry Real • Janis A. Spring • Jeffrey Zeig LAWS & ETHICS Workshop A. Steven Frankel, PhD,JD Sponsored by THE :MILTON H. ERICKSON FOUNDATION, INC., Phoenix, AZ with Organization by THE COUPLES INSTITUTE, Menlo Park, CA 8:15-8:30 AM Opening Remarks Emerald Ballroom 8:30-9:30 AM Keynote Address 1 - Ayala Pines - How We Choose the Lovers We Emerald Ballroom Choose and Why This Question is Important for Couples Therapists 9:45 AM-12:45 PM Workshops WS 1 - Getting Off to a Powerful Start- Ellyn Bader Gold Rush Ballroom WS 2 - Relationships Make Me Sick- Jock McKeen & Bennet Wong Redwood Room WS 3- The Silent Divorce: Anxiety, Depression and Relationships- Pat Love Emerald Ballroom 2:00-5:00 PM Workshops WS 4 - Existential Issues in Sexuality- Marty Klein Gold Rush Ballroom WS 5 - Keeping the Spark Alive: How to Prevent Burnout in Love and Marriage - Ayala Pines Redwood Room WS 6 - Twelve Strategies for Solving Marital Problems - Cloe Madanes Emerald Ballroom 5:15-6:15 PM Conversation Hour CH 1 - Viagra- Part of the Solution or Part of the Problem - Marty Klein Gold Rush Ballroom FRIDAY, JUNE 13, 2003 8:00 AM-12:00 N Laws & Ethics Workshop, Part 1- Steven Frankel Redwood Room Laws & Ethics Update for Clinicians Working with Families & Children 9:00 AM-12:00 N Workshops WS 7 -After the Affair: -

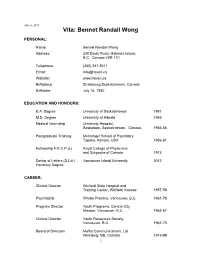

Vita: Bennet Randall Wong

June 6, 2013 Vita: Bennet Randall Wong PERSONAL: Name: Bennet Randall Wong Address: 240 Davis Road, Gabriola Island, B.C. Canada V0R 1X1 Telephone: (250) 247-9211 Email: [email protected] Website: www.haven.ca Birthplace: Strasbourg,Saskatchewan, Canada Birthdate: July 16, 1930 EDUCATION AND HONOURS: B.A. Degree University of Saskatchewan 1951 M.D. Degree University of Alberta 1955 Medical Internship University Hospital, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, 1955-56 Postgraduate Training Menninger School of Psychiatry Topeka, Kansas, USA 1956-61 Fellowship F.R.C.P.(c) Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada 1973 Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) Vancouver Island University 2012 Honorary Degree CAREER: Clinical Director Winfield State Hospital and Training Center, Winfield, Kansas 1957-59 Psychiatrist Private Practice, Vancouver, B.C. 1961-75 Program Director Youth Programs, Central City Mission, Vancouver, B.C. 1963-67 Clinical Director Youth Resources Society, Vancouver, B.C. 1967-70 Board of Directors Moffat Communications, Ltd. Winnipeg, MB, Canada 1973-99 1 Clinical Instructor Department of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. 1974-80 Co-Director Resident Fellow Program, Cold Mountain Institute, Cortes Island, B.C. 1975-80 Board of Directors Cold Mountain Institute, Vancouver, B.C. 1972-80 Faculty Antioch College West, M.A. Program in Humanistic Psychology 1974-80 Board of Directors Cortes Centre for Human Development 1980-88 Advisory Board Hull Institute, Calgary, AB, Canada 1985-88 Board of Advisors Options for Children and Families Calgary, Alberta 1987-93 Board of Advisors The Haven Institute, Gabriola, B.C. 1995 -2004 Director PD Seminars Ltd., Gabriola, B.C.