Fungi in Liverwort-Based Biocrust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castanedospora, a New Genus to Accommodate Sporidesmium

Cryptogamie, Mycologie, 2018, 39 (1): 109-127 © 2018 Adac. Tous droits réservés South Florida microfungi: Castanedospora,anew genus to accommodate Sporidesmium pachyanthicola (Capnodiales, Ascomycota) Gregorio DELGADO a,b*, Andrew N. MILLER c & Meike PIEPENBRING b aEMLab P&K Houston, 10900 BrittmoorePark Drive Suite G, Houston, TX 77041, USA bDepartment of Mycology,Institute of Ecology,Evolution and Diversity, Goethe UniversitätFrankfurt, Max-von-Laue-Str.13, 60438 Frankfurt am Main, Germany cIllinois Natural History Survey,University of Illinois, 1816 South Oak Street, Champaign, IL 61820, USA Abstract – The taxonomic status and phylogenetic placement of Sporidesmium pachyanthicola in Capnodiales(Dothideomycetes) are revisited based on aspecimen collected on the petiole of adead leaf of Sabal palmetto in south Florida, U.S.A. New evidence inferred from phylogenetic analyses of nuclear ribosomal DNA sequence data together with abroad taxon sampling at family level suggest that the fungus is amember of Extremaceaeand therefore its previous placement within the broadly defined Teratosphaeriaceae was not supported. Anew genus Castanedospora is introduced to accommodate this species on the basis of its distinct morphology and phylogenetic position distant from Sporidesmiaceae sensu stricto in Sordariomycetes. The holotype material from Cuba was found to be exhausted and the Florida specimen, which agrees well with the original description, is selected as epitype. The fungus produced considerably long cylindrical to narrowly obclavate conidia -

Environment and the Distribution of Microfungi in a Hawaiian Mangrove Swampl BENNY K

Environment and the Distribution of Microfungi in a Hawaiian Mangrove Swampl BENNY K. H. LEE2 AND GLADYS E. BAKER2 EXTENSIVE INVESTIGATIONS of the ecological effect of temperature and salinity on the growth relationships of soil microfungi with soil types, rate of these fungi. Further study concerned pH, moisture, horizon, temperature, and macro the effects of mangrove root extract and man· vegetation have been published (Parkinson and grove swamp soil extract on fungal growth. Waid, 1960; Alexander, 1961; and Burges and Raw, 1967). It is a well-established principle MATERIALS AND METHODS that soil fungi are influenced by specific soil environments. Mangroves occupy a littoral hab Test Organisms itat, characterized almost invariably by salt or Five fungi were selected from different brackish water and coastal silt. The microfungi salinity levels in the Heeia mangrove swamp. in the mangrove swamp must be able to tolerate All were used in the salinity tolerance tests; the the conditions characteristic of this special first three were used to determine the inter ecosystem: Their distribution in particular may action of salinity and temperature. be affected by the salinity of the mangrove ISOLATES FROM HIGH SALINITY SITES: Robil swamp (Swart, 1958; and Kohlmeyer, 1969). larda rhizophorae Kohlm. was isolated from Tolerance to different salinity levels may cor submerged dead prop roots of Rhizophora relate with temperature levels as demonstrated mangle 1. at the seaward side of Heeia swamp by Ritchie (1957, 1959) in a series of in vitro near the fishpond. The Idcation corresponds experiments. For those microfungi occurring in to station 5 of Walsh (1967). Salinity readings association with the mangrove roots, it is also obtained monthly between August 1961 and necessary to consider the influence of the root November 1962 varied from 0.73 to 29.34 itself and the rhizosphere effect. -

Long-Term Changes in Biological Soil Crust Cover and Composition Eva Dettweiler-Robinson1*, Jeanne M Ponzetti2 and Jonathan D Bakker3

Dettweiler-Robinson et al. Ecological Processes 2013, 2:5 http://www.ecologicalprocesses.com/content/2/1/5 RESEARCH Open Access Long-term changes in biological soil crust cover and composition Eva Dettweiler-Robinson1*, Jeanne M Ponzetti2 and Jonathan D Bakker3 Abstract Introduction: Communities change over time due to disturbances, variations in climate, and species invasions. Biological soil crust communities are important because they contribute to erosion control and nutrient cycling. Crust types may respond differently to changes in environmental conditions: single-celled organisms and bryophytes quickly recover after a disturbance, while lichens are slow growing and dominate favorable sites. Community change in crusts has seldom been assessed using repeated measures. For this study, we hypothesized that changes in crust composition were related to disturbance, topographic position, and invasive vegetation. Methods: We monitored permanent plots in the Columbia Basin in 1999 and 2010 and compared changes in crust composition, cover, richness, and turnover with predictor variables of herbivore exclosure, elevation, heat load index, time since fire, presence of an invasive grass, and change in cover of the invasive grass. Results: Bryophytes were cosmopolitan with high cover. Dominant lichens did not change dramatically. Indicator taxa differed by monitoring year. Bryophyte and total crust cover declined, and there was lower turnover outside of herbivore exclosures. Lichen cover did not change significantly. Plots that burned recently had high turnover. Increase in taxon richness was correlated with presence of an invasive grass in 1999. Change in cover of the invasive grass was positively related to proportional loss and negatively related to gain. Conclusions: Composition and turnover metrics differed significantly over 11 years, though cover was more stable between years. -

Biological Soil Crust Community Types Differ in Key Ecological Functions

UC Riverside UC Riverside Previously Published Works Title Biological soil crust community types differ in key ecological functions Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2cs0f55w Authors Pietrasiak, Nicole David Lam Jeffrey R. Johansen et al. Publication Date 2013-10-01 DOI 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.05.011 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Soil Biology & Biochemistry 65 (2013) 168e171 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Soil Biology & Biochemistry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/soilbio Short communication Biological soil crust community types differ in key ecological functions Nicole Pietrasiak a,*, John U. Regus b, Jeffrey R. Johansen c,e, David Lam a, Joel L. Sachs b, Louis S. Santiago d a University of California, Riverside, Soil and Water Sciences Program, Department of Environmental Sciences, 2258 Geology Building, Riverside, CA 92521, USA b University of California, Riverside, Department of Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA c Biology Department, John Carroll University, 1 John Carroll Blvd., University Heights, OH 44118, USA d University of California, Riverside, Botany & Plant Sciences Department, 3113 Bachelor Hall, Riverside, CA 92521, USA e Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branisovska 31, 370 05 Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic article info abstract Article history: Soil stability, nitrogen and carbon fixation were assessed for eight biological soil crust community types Received 22 February 2013 within a Mojave Desert wilderness site. Cyanolichen crust outperformed all other crusts in multi- Received in revised form functionality whereas incipient crust had the poorest performance. A finely divided classification of 17 May 2013 biological soil crust communities improves estimation of ecosystem function and strengthens the Accepted 18 May 2013 accuracy of landscape-scale assessments. -

Biological Soil Crust Rehabilitation in Theory and Practice: an Underexploited Opportunity Matthew A

REVIEW Biological Soil Crust Rehabilitation in Theory and Practice: An Underexploited Opportunity Matthew A. Bowker1,2 Abstract techniques; and (3) monitoring. Statistical predictive Biological soil crusts (BSCs) are ubiquitous lichen–bryo- modeling is a useful method for estimating the potential phyte microbial communities, which are critical structural BSC condition of a rehabilitation site. Various rehabilita- and functional components of many ecosystems. How- tion techniques attempt to correct, in decreasing order of ever, BSCs are rarely addressed in the restoration litera- difficulty, active soil erosion (e.g., stabilization techni- ture. The purposes of this review were to examine the ques), resource deficiencies (e.g., moisture and nutrient ecological roles BSCs play in succession models, the augmentation), or BSC propagule scarcity (e.g., inoc- backbone of restoration theory, and to discuss the prac- ulation). Success will probably be contingent on prior tical aspects of rehabilitating BSCs to disturbed eco- evaluation of site conditions and accurate identification systems. Most evidence indicates that BSCs facilitate of constraints to BSC reestablishment. Rehabilitation of succession to later seres, suggesting that assisted recovery BSCs is attainable and may be required in the recovery of of BSCs could speed up succession. Because BSCs are some ecosystems. The strong influence that BSCs exert ecosystem engineers in high abiotic stress systems, loss of on ecosystems is an underexploited opportunity for re- BSCs may be synonymous with crossing degradation storationists to return disturbed ecosystems to a desirable thresholds. However, assisted recovery of BSCs may trajectory. allow a transition from a degraded steady state to a more desired alternative steady state. In practice, BSC rehabili- Key words: aridlands, cryptobiotic soil crusts, cryptogams, tation has three major components: (1) establishment of degradation thresholds, state-and-transition models, goals; (2) selection and implementation of rehabilitation succession. -

Water Regulation in Cyanobacterial Biocrusts from Drylands: Negative Impacts of Anthropogenic Disturbance

water Article Water Regulation in Cyanobacterial Biocrusts from Drylands: Negative Impacts of Anthropogenic Disturbance Yolanda Cantón 1,2,*, Sonia Chamizo 1,2, Emilio Rodriguez-Caballero 1,2 , Roberto Lázaro 3, Beatriz Roncero-Ramos 1 , José Raúl Román 1 and Albert Solé-Benet 3 1 Department of Agronomy, University of Almeria, Carretera de Sacramento sn., La Cañada de San Urbano, 04120 Almeria, Spain; [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (E.R.-C.); [email protected] (B.R.-R.); [email protected] (J.R.R.) 2 Research Centre for Scientific Collections from the University of Almería (CECOUAL), Carretera de Sacramento sn., La Cañada de San Urbano, 04120 Almeria, Spain 3 Experimental Station of Arid Zones, CSIC, Carretera de Sacramento sn., La Cañada de San Urbano, 04120 Almeria, Spain; [email protected] (R.L.); [email protected] (A.S.-B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 December 2019; Accepted: 4 March 2020; Published: 6 March 2020 Abstract: Arid and semi-arid ecosystems are characterized by patchy vegetation and variable resource availability. The interplant spaces of these ecosystems are very often covered by cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts, which are the primary colonizers of terrestrial ecosystems and key in facilitating the succession of other biocrust organisms and plants. Cyanobacterial biocrusts regulate the horizontal and vertical fluxes of water, carbon and nutrients into and from the soil and play crucial hydrological, geomorphological and ecological roles in these ecosystems. In this paper, we analyze the influence of cyanobacterial biocrusts on water balance components (infiltration-runoff, evaporation, soil moisture and non-rainfall water inputs (NRWIs)) in representative semiarid ecosystems in southeastern Spain. -

National Cooperative Soil Survey and Biological Soil Crusts

Biological Soil Crusts Status Report 2003 National Cooperative Soil Survey Conference Plymouth, Massachusetts June 16 - 20, 2003 Table of Contents I. NCSS 2003 National Conference Proceedings II. Report and recommendations of the soil crust task force - 2002 West Regional Cooperative Soil Survey Conference Task Force Members Charges Part I. Executive Summary and Recommendations Part II. Report on Charges Part III. Research Needs, Action Items, Additional Charges Part IV. Resources for Additional Information Part V. Appendices Appendix 1 - Agency needs Appendix 2 - Draft material for incorporation into the Soil Survey Manual Introduction Relationship to Mineral Crusts Types of Biological Soil Crusts Figure 1. Biological soil crust types. Major Components of Soil Crusts: Cyanobacteria, Lichens, and Mosses Table 1. Morphological groups for biological crust components and their N-fixing characteristics. (Belnap et al. 2001) Soil Surface Roughness/Crust Age Distribution of Crusts References Appendix 3 - Guidelines for describing soil surface features, Version 2.0 Surface features Table 1. Surface features Determining Percent Cover Equipment Method 1. Step-point Method 2. Ocular estimate with quadrats Method 3. Line-point quadrat Method 4. Stratified line-point intercept Method 5. Ocular estimate Appendix 3a - Data sheets used in Moab field test Appendix 4 - Soil descriptions Discussion Group 1 Group 3 Group 2 Group 4 Appendix 5 - Photography Biological Soil Crust Status Report NCSS National Conference June 16-20, 2003 Table of Contents III. Task force's response to the following questions posed by the 2002 West Regional Standards Committee 1. Are biological soil crusts plants, soil or combination of both? 2. Is it appropriate to think of these crusts as plant communities with potentials, state and transition? 3. -

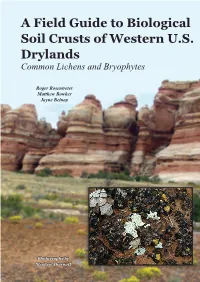

A Field Guide to Biological Soil Crusts of Western U.S. Drylands Common Lichens and Bryophytes

A Field Guide to Biological Soil Crusts of Western U.S. Drylands Common Lichens and Bryophytes Roger Rosentreter Matthew Bowker Jayne Belnap Photographs by Stephen Sharnoff Roger Rosentreter, Ph.D. Bureau of Land Management Idaho State Office 1387 S. Vinnell Way Boise, ID 83709 Matthew Bowker, Ph.D. Center for Environmental Science and Education Northern Arizona University Box 5694 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 Jayne Belnap, Ph.D. U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center Canyonlands Research Station 2290 S. West Resource Blvd. Moab, UT 84532 Design and layout by Tina M. Kister, U.S. Geological Survey, Canyonlands Research Station, 2290 S. West Resource Blvd., Moab, UT 84532 All photos, unless otherwise indicated, copyright © 2007 Stephen Sharnoff, Ste- phen Sharnoff Photography, 2709 10th St., Unit E, Berkeley, CA 94710-2608, www.sharnoffphotos.com/. Rosentreter, R., M. Bowker, and J. Belnap. 2007. A Field Guide to Biological Soil Crusts of Western U.S. Drylands. U.S. Government Printing Office, Denver, Colorado. Cover photos: Biological soil crust in Canyonlands National Park, Utah, cour- tesy of the U.S. Geological Survey. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................... 4 How to use this guide .................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................... 4 Crust composition .................................................................................. -

Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United

Richard V. Pouyat Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Toral Patel-Weynand Linda H. Geiser Editors Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions A Comprehensive Science Synthesis Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions Richard V. Pouyat • Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Toral Patel-Weynand • Linda H. Geiser Editors Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions A Comprehensive Science Synthesis Editors Richard V. Pouyat Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Northern Research Station Rocky Mountain Research Station USDA Forest Service USDA Forest Service Newark, DE, USA Moscow, ID, USA Toral Patel-Weynand Linda H. Geiser Washington Office Washington Office USDA Forest Service USDA Forest Service Washington, DC, USA Washington, DC, USA ISBN 978-3-030-45215-5 ISBN 978-3-030-45216-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45216-2 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 . This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. -

Microbial Biobanking – Cyanobacteria-Rich Topsoil Facilitates Mine Rehabilitation

Biogeosciences, 16, 2189–2204, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-2189-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Microbial biobanking – cyanobacteria-rich topsoil facilitates mine rehabilitation Wendy Williams1, Angela Chilton2, Mel Schneemilch1, Stephen Williams1, Brett Neilan3, and Colin Driscoll4 1School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, The University of Queensland, Gatton Campus 4343, Australia 2Australian Centre for Astrobiology and School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia 3School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, 2308, Australia 4Hunter Eco, P.O. Box 1047, Toronto, NSW, 2283, Australia Correspondence: Wendy Williams ([email protected]) Received: 13 November 2017 – Discussion started: 20 November 2017 Revised: 10 January 2019 – Accepted: 23 January 2019 – Published: 28 May 2019 Abstract. Restoration of soils post-mining requires key so- tial for biocrust re-establishment. In general, the resilience lutions to complex issues through which the disturbance of of cyanobacteria to burial in topsoil stockpiles in both the topsoil incorporating soil microbial communities can result short and long term was significant; however, in an arid en- in a modification to ecosystem function. This research was in vironment recolonisation and community diversity could be collaboration with Iluka Resources at the Jacinth–Ambrosia impeded by drought. Biocrust re-establishment during mine (J–A) mineral sand mine located in a semi-arid chenopod rehabilitation relies on the role of cyanobacteria as a means shrubland in southern Australia. At J–A, assemblages of mi- of early soil stabilisation. At J–A mine operations do not croorganisms and microflora inhabit at least half of the soil threaten the survival of any of the organisms we studied. -

Biological Soil Crusts: Ecology and Management

BIOLOGICAL SOIL CRUSTS: ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT Technical Reference 1730-2 2001 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management U.S. Geological Survey Biological Soil Crusts: Ecology & Management This publication was jointly funded by the USDI, BLM, and USGS Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center. Though this document was produced through an interagency effort, the following BLM numbers have been assigned for tracking and administrative purposes: Technical Reference 1730-2 BLM/ID/ST-01/001+1730 Biological Soil Crusts: Ecology & Management Biological Soil Crusts: Ecology and Management Authors: Jayne Belnap Julie Hilty Kaltenecker USDI Geological Survey Boise State University/USDI Bureau of Land Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center Management Moab, Utah Idaho State Office, BLM Boise, Idaho Roger Rosentreter John Williams USDI Bureau of Land Management USDA Agricultural Research Service Idaho State Office Columbia Plateau Conservation Research Center Boise, Idaho Pendleton, Oregon Steve Leonard David Eldridge USDI Bureau of Land Management Department of Land and Water Conservation National Riparian Service Team New South Wales Prineville, Oregon Australia Illustrated by Meggan Laxalt Edited by Pam Peterson Produced By United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Printed Materials Distribution Center BC-650-B P.O. Box 25047 Denver, Colorado 80225-0047 Technical Reference 1730-2 2001 Biological Soil Crusts: Ecology & Management ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We gratefully acknowledge the following individuals -

Occurrence of Non-Obligate Microfungi Inside Lichen Thalli

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Sydowia Jahr/Year: 2005 Band/Volume: 57 Autor(en)/Author(s): Suryanarayanan Trichur Subramanian, Thirunavukkarasu N., Hariharan G. N., Balaji P. Artikel/Article: Occurrence of non-obligate microfungi inside lichen thalli. 120-130 ©Verlag Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges.m.b.H., Horn, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Occurrence of non-obligate microfungi inside lichen thalli T. S. Suryanarayanan1, N. Thirunavukkarasu1, G. N. Hariharan2 and P. Balajr 1 Vivekananda Institute of Tropical Mycology, Ramakrishna Mission Vidyapith, Chennai 600 004, India; 2 M S Swaminathan Research Foundation, Taramani, Chennai 600 113, India. Suryanarayanan, T. S., N. Thirunavukkarasu, G. N. Hariharan & P. Balaji (2005): Occurrence of non-obligate microfungi inside lichen thalli. - Sydowia 57 (1): 120-130. Five corticolous lichen species (four foliose and one fruticose) and the leaf and bark tissues of their host trees were screened for the presence of asympto- matic, culturable microfungi. Four isolation procedures were evaluated to identify the most suitable one for isolating the internal mycobiota of lichens. A total of 242 isolates of 21 fungal genera were recovered from 500 thallus segments of the lichens. Different fungi dominated the fungal assemblages of the lichen thalli and the host tissues. An ordination analysis showed that there was little overlap between the fungi of the lichens and those of the host tissues even though, con- sidering their close proximity, they must have been exposed to the same fungal inoculum. This is the first study that compares the microfungal assemblage asso- ciated with lichens with those occurring in their substrates.