Durham's Self-Help and the Financialization of the Bull City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Screenwriting 1: the 5 Elements

Introduction to screenwriting 1: The 5 elements by Allen Palmer Session 1 Introduction www.crackingyarns.com.au 1 Can we find a movie we all love? •Avatar? •Lord of the Rings? •Star Wars? •Groundhog Day? •Raiders of the Lost Ark? •When Harry Met Sally? 2 Why do people love movies? •Entertained •Escape •Educated •Provoked •Affirmed •Transported •Inspired •Moved - laugh, cry 3 Why did Aristotle think people loved movies? •Catharsis •Emotional cleansing or purging •What delivers catharsis? •Seeing hero undertake journey that transforms 4 5 “I think that what we’re seeking is an experience of being alive ... ... so that we can actually feel the rapture being alive.” Joseph Campbell “The Power of Myth” 6 What are audiences looking for? • Expand emotional bandwidth • Reminder of higher self • Universal connection • In summary ... • Cracking yarns 7 8 Me 9 You (in 1 min or less) •Name •Day job •Done any courses? Read any books? Written any screenplays? •Have a concept? •Which film would you like to have written? 10 What’s the hardest part of writing a cracking screenplay? •Concept? •Characters? •Story? •Scenes? •Dialogue? 11 Typical script report Excellent Good Fair Poor Concept X Character X Dialogue X Structure X Emotional Engagement X 12 Story without emotional engagement isn’t story. It’s just plot. 13 Plot isn’t the end. It’s just the means. 14 Stories don’t happen in the head. They grab us by the heart. 15 What is structure? •The craft of storytelling •How we engage emotions •How we generate catharsis •How we deliver what audiences crave 16 -

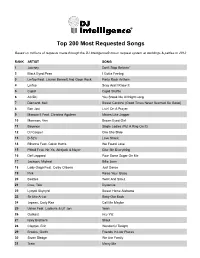

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

Durham: City of Champions

TWO DAY ITINERARY Where great things happen Durham: City of Champions Durham is home to national championships, hall of fame coaches, and the backdrop for the movie Bull Durham. While visitors do not go wanting for teams to root for or sporting events to attend, they also have opportunity to get active in Durham’s many recreation DAY 1 Located in Downtown Durham at Durham Central Park (501 Foster St), the skatepark is on the Rigsbee St side Durham Central Park Skatepark 501 Foster St, Durham, NC 27701 | (919) 682-2800 | www.durhamcentralpark.org/park-info/skate-park 1 markschuelerphoto.com 1 Start downtown with a visit to the Durham Central Park Skatepark. This 10,000-sq-ft. state-of- the-art park features a fl oating quarter pipe, three stairwells with handrails and an eight-foot trog bowl among other skater favorites. Helmets and pads are required! (Allow one hour) From Downtown Rigsbee St head south to W Chapel Hill St, turn left; follow and turn left onto 15-501 N Roxboro St; take the next right onto Hwy 98 E Holloway St (10 mins) (N) Wheels Fun Park 2 715 N Hoover Rd, Durham, NC 27712 | (919) 598-1944 | www.wheelsfunparkdurham.com Kids will go nuts for the attractions at Wheels Fun Park. From go-karts and mini golf to 4 1 (DT) batting cages and a roller skating rink, there are plenty of activities to keep the whole family 2 entertained. Open M-F 10am-9pm, F-Sa 10am-10pm, Su 1pm-7pm. (Allow 1-2 hours) (WC) (E) 3 Return to Hwy 98 and take Hwy 70 S to S Miami Blvd; take a right onto Ellis Rd, then first right onto (SE) Cash/Stage Rd (10 mins) (SW) DPR Ropes Course 1814 Stage Rd, Durham, NC 27703 DCVB Planning Assistance 3 (919) 560-4405 | www.durhamnc.gov The Durham Convention & Visitors Bureau sales and services staff are ready to help make The Discovery High Ropes Course pushes your visit to Durham a success. -

EDITORIAL Screenwriters James Schamus, Michael France and John Turman CA 90049 (310) 447-2080 Were Thinking Is Unclear

screenwritersmonthly.com | Screenwriter’s Monthly Give ‘em some credit! Johnny Depp's performance as Captain Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl is amazing. As film critic after film critic stumbled over Screenwriter’s Monthly can be found themselves to call his performance everything from "original" to at the following fine locations: "eccentric," they forgot one thing: the screenwriters, Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, who did one heck of a job creating Sparrow on paper first. Sure, some critics mentioned the writers when they declared the film "cliché" and attacked it. Since the previous Walt Disney Los Angeles film based on one of its theme park attractions was the unbear- able The Country Bears, Pirates of the Caribbean is surprisingly Above The Fold 370 N. Fairfax Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90036 entertaining. But let’s face it. This wasn't intended to be serious (323) 935-8525 filmmaking. Not much is anymore in Hollywood. Recently the USA Today ran an article asking, basically, “What’s wrong with Hollywood?” Blockbusters are failing because Above The Fold 1257 3rd St. Promenade Santa Monica, CA attendance is down 3.3% from last year. It’s anyone’s guess why 90401 (310) 393-2690 this is happening, and frankly, it doesn’t matter, because next year the industry will be back in full force with the same schlep of Above The Fold 226 N. Larchmont Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90004 sequels, comic book heroes and mindless action-adventure (323) 464-NEWS extravaganzas. But maybe if we turn our backs to Hollywood’s fast food service, they will serve us something different. -

William J. Maxwell Curriculum Vitae August 2021

William J. Maxwell curriculum vitae August 2021 Professor of English and African and African-American Studies Washington University in St. Louis 1 Brookings Drive St. Louis, MO 63130-4899 U.S.A. Phone: (217) 898-0784 E-mail: [email protected] _________________________________________ Education: DUKE UNIVERSITY, DURHAM, NC. Ph.D. in English Language and Literature, 1993. M.A. in English Language and Literature, 1987. COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, NEW YORK, NY. B.A. in English Literature, cum laude, 1984. Academic Appointments: WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS, MO. Professor of English and African and African-American Studies, 2015-. Director of English Undergraduate Studies, 2018- 21. Faculty Affiliate, American Culture Studies, 2011-. Director of English Graduate Studies, 2012-15. Associate Professor of English and African and African-American Studies, 2009-15. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN, IL. Associate Professor of English and the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory, 2000-09. Director of English Graduate Studies, 2003-06. Assistant Professor of English and Afro-American Studies, 1994-2000. COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY, WILLIAMSBURG, VA. Visiting Assistant Professor of English, 1996-97. UNIVERSITY OF GENEVA, GENEVA, SWITZERLAND. Assistant (full-time lecturer) in American Literature and Civilization, 1992-94. Awards, Fellowships, and Professional Distinctions: Claude McKay’s lost novel Romance in Marseille, coedited with Gary Edward Holcomb, named one of the ten best books of 2020 by New York Magazine, 2021. Appointed to the Editorial Board of James Baldwin Review, 2019-. Elected Second Vice President (and thus later President) of the international Modernist Studies Association (MSA), 2018; First Vice President, 2019-20; President, 2021-. American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation for my 2015 book F.B. -

Former Austin Peay Coach Assistant Principal at 70

CMA Celebrates 100th Anniversary At Next Year’s Grand Reunion ILITARY M A IA C B A M D U E L M O Y C • A • QUI SE VINC CIT N L I T V I N U IO BUGLE M T QUARTERLY N A I ASSOCI Volume 13, Number 2 Summer, 2003 where he went to school prior to attending Former Austin Peay Coach CMA. He remains an assistant principal at the town’s elementary school, he hasn’t yet decided when he’ll close the final door on Assistant Principal at 70 a life of influencing kids. Kelly’s first departure from Clarksville Lake Kelly, CMA Class took him to Oral Roberts where he coached of ‘52 has fond memories for three seasons and compiled a 30 and of taking the Austin Peay 24 record. Then spent four years at Clark Governors to three NCAA County High School in Winchester, KY., basketball appearances. and 2 seasons as an assistant to Joe B. Hall In 1987 the team was at Kentucky before a return to Clarksville ranked 14 in the nation where he replaced Howard Jackson, one of knocking the number three his former players who had coached Austin seed, Illinois, off before nar- Peay for two years. rowly losing to Providence Jackson beams when asked about who went on to the final Coach Kelly. Following a construction four. accident that broke both of Jackson’s legs, His victory over the Il- Kelly helped nurse him back to health in lini forced ESPN’s resident the Fall of ‘73. -

Vinyl, Digital & MP3 Internet Music Pool

S.U.R.E. DJ COALITION Vinyl, Digital & MP3 Internet Music Pool “EAR 2 THA Headphone” THE BI-MONTHLY E-MAIL PUBLICATION THAT DEALS SOLELY WITH MP3 SERVICED TO S.U.R.E.’S MEMBERSHIP WITHIN THE LAST SIX WEEKS. THE VARIOUS CHARTS PROVIDE DJ’S WITH AN INSIGHT TO UNRELEASED AND CURRENT TITLES THAT ARE CIRCULATING ON THE STREETS AND AVAILABLE FOR THEM TO PROGRAM. VOLUME # 2 / ISSUE # 2 / MARCH 15 - 31 2007 NEW & HOT S.U.R.E.SHOTS! Ahmir – Right To Left - Echo Paul Wall – I’m Throwed - Asylum Slim Thug – Problem Wit Dat - Geffen Crime Mob – 2nd Look – BME / Reprise Young Chris – Coast To Coast – Def Jam TOP TUNES IN THE BIG APPLE! Musiq Soul Child – Buddy - Atlantic Mims – This Is Why I’m Hot - Capitol Wayne Wonder - Gonna Lve You - VP Consequence – Callin’ Me - Columbia Pretty Ricky – On The Hotline - Atlantic PRIME CHART MOVERS! Young Buck – Haters – G Unit Mike Jones – Mr Jones – Warner Brick & Lace – Never Never - Geffen Timbaland – Give It To Me – Interscope Kelly Rowland ft Eve – Like This - Columbia TOP TURNTABLE ADDS! Clyde Carson – 2 Step - Capitol Notch – Guaya Guaya – Machete Rich Boy – Boy Looka Here - Interscope Ms Triniti – Bongce Along – Unseen Lab Fabolous ft Young Jeezy – Diamond – Def Jam THE TOP INDIES RELEASES! Rizz – Ready 4 It – The Outfit Em J ft Beenie Man – Get Loose – Emjay Sugar Kaine – Just Another Booty Song - Kolor Drag On ft Tahmeik – Ok Daddy - B Boy Records Euricka ft Calvin Richardson – On My Own - Echo HOT PROMOTIONAL CD’S! Vi ft Glc – Hurta - Mathaus D Lee – TNA – Trump Tight Carl Henry – Encore – Cesoul K Janai – Checkin Me – Blaq Roc J Peezy – This Old School – APB B.O.B – Heavy Breather – Atlantic Papa Reu - “Cellular – R E Umuzik Mardi Gra – Freak Off – Klique City Ill Nature – U Know What’s Up – I.N. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

![Cam'ron, Roc Army [DJ Clue] Part 1!](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1581/camron-roc-army-dj-clue-part-1-1041581.webp)

Cam'ron, Roc Army [DJ Clue] Part 1!

Cam'ron, Roc Army [DJ Clue] Part 1! [Memphis Bleek] The Roc! [Jay-Z] Roc, yeah y'all it's the Roc [DJ Clue] New shit, Roc Army (Chorus) [Scratches (Jay-Z)] "Memph, Memph, Memph, Memph Bleek" <--- Memphis Bleek (Roc-a-fella is the Army) "Mac, Mac, Mac" <--- Beanie Sigel "Sparks, O" <--- Jay-Z (Roc-a-fella is the Army) "Lil Chris, Lil Neef" <--- Beanie Sigel "Freeway" <--- Jay-Z (Roc-a-fella is the Army) "Killa," "Cam'Ron" <--- Cam'Ron "Jigga" <--- Jay-Z ("R-O-C Niggas") <--- Jay-Z (Roc-a-fella is the Army) [DJ Clue over the chorus] Jay-Z, Peedi Crakk Cam'Ron, Freeway What Clue [Jay-Z] Illest since the Row had it, nigga now the Roc got it Nigga get you blocka'ed lean em like a dope addict Hov the hustler, CD's a coke habit Ya dancing wit the devil, muh'fuckas is slow draggin (C'MON) Hov is big homie, Beanie is the co-captain [Freeway] I'll A.K. ya tee, don't forget about Free Chris and Neef, Sparks and Oski All my niggas on the streets get low with M. Bleek (Whew!) Who the fuck want what [Cam'Ron] It's the newest addition, mathematician Cracks in the kitchen, multiplication Rocks that I slash with precision Killa Cam Motherfucker [Freeway (Cam'Ron)] We got gats tearin the basement Mac in the car, clap from a distance (Kill ya man motherfucker) They track stars, half of them racin Run from the gate, straight to the district -

Nightlight: Tradition and Change in a Local Music Scene

NIGHTLIGHT: TRADITION AND CHANGE IN A LOCAL MUSIC SCENE Aaron Smithers A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Curriculum of Folklore. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Glenn Hinson Patricia Sawin Michael Palm ©2018 Aaron Smithers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Aaron Smithers: Nightlight: Tradition and Change in a Local Music Scene (Under the direction of Glenn Hinson) This thesis considers how tradition—as a dynamic process—is crucial to the development, maintenance, and dissolution of the complex networks of relations that make up local music communities. Using the concept of “scene” as a frame, this ethnographic project engages with participants in a contemporary music scene shaped by a tradition of experimentation that embraces discontinuity and celebrates change. This tradition is learned and communicated through performance and social interaction between participants connected through the Nightlight—a music venue in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Any merit of this ethnography reflects the commitment of a broad community of dedicated individuals who willingly contributed their time, thoughts, voices, and support to make this project complete. I am most grateful to my collaborators and consultants, Michele Arazano, Robert Biggers, Dave Cantwell, Grayson Currin, Lauren Ford, Anne Gomez, David Harper, Chuck Johnson, Kelly Kress, Ryan Martin, Alexis Mastromichalis, Heather McEntire, Mike Nutt, Katie O’Neil, “Crowmeat” Bob Pence, Charlie St. Clair, and Isaac Trogden, as well as all the other musicians, employees, artists, and compatriots of Nightlight whose combined efforts create the unique community that define a scene. -

Varsity Baseball Record2

Most Grand Slam Home Runs 4 1998 William Byrd Varsity Baseball Records( 1983- 2007 ) Most walks 157 2000 Most strikeouts TEAM RECORDS SEASON : 159 1994 Most wins 23 STATE RUNNER-UP 2000 Most stolen bases 76/81 1989 23 1992 22 STATE CHAMPIONS 1997 Most errors 21 1994 63 1989 Longest win streak Fewest errors 23 1992 22 1996 18 1994 Best fielding average Longest reg. season win streak .975 1996 34 1991, ’92. ‘93 Pitching E.R.A. Longest HOME win streak 1.57 1992 & 1996 21 1992-1993 Most shut-outs (WB pitchers) Most losses 6 1976; 1996; 2000 14 1981 Most consecutive shut-outs Fewest wins 4 1996 1 1980 & 81 Most cons. innings w/out an earned run Fewest losses 45 1996 1 1992 TEAM RECORDS GAME : Best winning percentage Most hits .958 1992 22 vs. Lord Botetourt 1991 Most runs 19 vs. Rockbridge Co. 1993 267 2000 18 vs. Lord Botetourt 1992 252 1999 18 vs. Blacksburg 2002 242 1992 18 vs. Alleghany 1991 & 1996 18 vs. Lord Botetourt 1985 Most runs ( opponents ) 145 2004 Most runs 30 vs. Patrick Henry 1992 Fewest runs 37 1970 23 vs. William Fleming 2007 22 vs. Blacksburg 2002 Fewest runs ( opponents ) 20 vs. Alleghany 1999 29 1973 19 vs. Rockbridge Co. 2000 Highest batting average 19 vs. Lord Botetourt 1991 & 1998 .368 1999 19 vs. Northside 1994 .358 1992 19 vs. Glenvar 1983 & 1988 19 vs. Radford 1985 Most singles 173 1997 Most runs ( opponents ) 24 vs. Northside 1980 Most doubles 55 2004 Most singles 14 vs. Glenvar 1995 Most triples 9 2000 Most doubles 8 vs. -

08 7-8 Sports.Indd 1 7/8/08 8:05:21 AM

Page 8 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, July 8, 2008 Norton Legion splits with Scott City By DICK BOYD “Our team is getting closer to [email protected] being set with just a few more The Norton American Legion positions to be solidified. We baseball team defeated Scott City changed our batting order and that 6-5 at John Ryan Field on Sunday, worked out well. June 29 but lost the second contest “We still make dumb mistakes 15-6. but the players know that if a coach In the opener, Scott City scored takes them out of the game it is not two runs in the top of the first but to punish them but to get them to Norton took a 3-2 lead with three fully understand what we are try- scores in the bottom of the inning. ing to instill in our team. Todd Zink led off with a single, “In our first game, Jordan Garrett Tacha walked, Jordan pitched a strong four innings be- Durham slammed a double and fore giving way to Garrett. These all three tallied. two young men are the pitching Scott City came back with two strength of our team as they have more runs in the top of the second pitched more than anyone else.” to make it 4-3. Norton did not In the second contest, Scott score in the bottom of the inning City scored six runs in the top of but Scott City was held scoreless the first inning, two more in the in the top of the third.