Ron Howard: the Past, Present and Future of Entertainment (EP.19)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibits Registrations

July ‘09 EXHIBITS In the Main Gallery MONDAY TUESDAY SATURDAY ART ADVISORY COUNCIL MEMBERS’ 6 14 “STREET ANGEL” (1928-101 min.). In HYPERTENSION SCREENING: Free 18 SHOW, throughout the summer. AAC MANHASSET BAY BOAT TOURS: Have “laughter-loving, careless, sordid Naples,” screening by St. Francis Hospital. 11 a.m. a look at Manhasset Bay – from the water! In the Photography Gallery a fugitive named Angela (Oscar winner to 2 p.m. A free 90-minute boat tour will explore Janet Gaynor) joins a circus and falls in Legendary Long the history and ecology of our corner of love with a vagabond painter named Gino TOPICAL TUESDAY: Islanders. What do Billy Joel, Martha Stew- Long Island Sound. Tour dates are July (Charles Farrell). Philip Klein and Henry art, Kiri Te Kanawa and astronaut Dr. Mary 18; August 8 and 29. The tour is free, but Roberts Symonds scripted, from a novel Cleave have in common? They have all you must register at the Information Desk by Monckton Hoffe, for director Frank lived on Long Island and were interviewed for the 30 available seats. Registration for Borzage. Ernest Palmer and Paul Ivano by Helene Herzig when she was feature the July 18 tour begins July 2; Registration provided the glistening cinematography. editor of North Shore Magazine. Herzig has for the August tours begins July 21. Phone Silent with orchestral score. 7:30 p.m. collected more than 70 of her interviews, registration is acceptable. Tours at 1 and written over a 20-year period. The celebri- 3 p.m. Call 883-4400, Ext. -

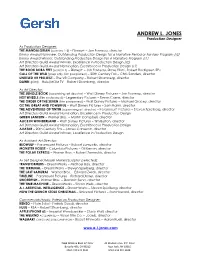

JONES-A.-RES-1.Pdf

ANDREW L. JONES Production Designer As Production Designer: THE MANDALORIAN (seasons 1-3) – Disney+ – Jon Favreau, director Emmy Award Nominee, Outstanding Production Design for a Narrative Period or Fantasy Program (s2) Emmy Award Winner, Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Program (s1) Art Directors Guild Award Winner, Excellence in Production Design (s2) Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design (s1) THE BOOK BOBA FETT (season 1) – Disney+ – Jon Favreau, Dave Filoni, Robert Rodriguez, EPs CALL OF THE WILD (prep only, film postponed) – 20th Century Fox – Chris Sanders, director UNTITLED VR PROJECT – The VR Company – Robert Stromberg, director DAWN (pilot) – Hulu/MGM TV – Robert Stromberg, director As Art Director: THE JUNGLE BOOK (supervising art director) – Walt Disney Pictures – Jon Favreau, director HOT WHEELS (film postponed) – Legendary Pictures – Simon Crane, director THE ORDER OF THE SEVEN (film postponed) – Walt Disney Pictures – Michael Gracey, director OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL – Walt Disney Pictures – Sam Raimi, director THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN (supervising art director) – Paramount Pictures – Steven Spielberg, director Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design GREEN LANTERN – Warner Bros. – Martin Campbell, director ALICE IN WONDERLAND – Walt Disney Pictures – Tim Burton, director Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design AVATAR – 20th Century Fox – James Cameron, director Art Directors Guild Award Winner, Excellence in Production Design As Assistant Art Director: BEOWULF – Paramount Pictures – Robert Zemeckis, director MONSTER HOUSE – Columbia Pictures – Gil Kenan, director THE POLAR EXPRESS – Warner Bros. – Robert Zemeckis, director As Set Designer/Model Maker/Sculptor (selected): TRANSFORMERS – DreamWorks – Michael Bay, director THE TERMINAL – DreamWorks – Steven Spielberg, director THE LAST SAMURAI – Warner Bros. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

CBS Cuts $ on CD Front -Lines

iUI 908 (t,14 **,;t*A,<*fi,? *3- DIGIT 4401 8812 MAR90UHZ 000117973 MONTY GREENLY APT A TOP 3740 ELM 90P07 LONG BEACH CA CONCERTS & VENUES Follows page 56 VOLUME 100 NO. 13 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT March 26, 1988/$3.95 (U.S.), $5 (CAN.) 3-Inch CD Gets Big Play Dealers Get A Big Spring Break As Majors Start Ball Rolling CD Front This story was prepared by Dave said Lew Garrett, vice president of CBS Cuts $ On -lines DiMartino and Geoff Mayfield. purchasing for North Canton, Ohio- will cut prices on selected black, front -line level and will translate based Camelot Music, speaking at a BY KEN TERRY country, and new artist releases and roughly to a $1 drop in wholesale LOS ANGELES The 3 -inch compact seminar. "Now, we're more excited LOS ANGELES In a surprise MCA plans to reduce the cost of its cost. At the same time, CBS will disk got major play at the National about it." move that may have a profound ef- country CD releases (see story, start offering new and developing Assn. of Record- Discussion among many label exec- fect on industry page 71), the CBS package repre- artist product at the $12.98 list ing Merchandis- utives shifted from general concerns pricing of com- sents the most comprehensive as- equivalent, which represents a ers convention with product viability to more specific pact disks, CBS wholesale cut of about $2. NAHM here March 11 -14. matters of packaging. One executive HARM Records plans to Teller keynote, p. -

Sexuality Education for Mid and Later Life

Peggy Brick and Jan Lunquist New Expectations Sexuality Education for Mid and Later Life THE AUTHORS Peggy Brick, M.Ed., is a sexuality education consultant currently providing training workshops for professionals and classes for older adults on sexuality and aging. She has trained thousands of educators and health care professionals nationwide, is the author of over 40 articles on sexuality education, and was formerly chair of the Board of the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS). Jan Lunquist, M.A., is the vice president of education for Planned Parenthood Centers of West Michigan. She is certified as a sexuality educator by the American Association of Sex Educators, Counselors, and Therapists. She is also a certified family life educator and a Michigan licensed counselor. During the past 29 years, she has designed and delivered hundreds of learning experiences related to the life-affirming gift of sexuality. Cover design by Alan Barnett, Inc. Printing by McNaughton & Gunn Copyright 2003. Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036-7802. Phone: 212/819-9770. Fax: 212/819-9776. E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.siecus.org 2 New Expectations This manual is dedicated to the memory of Richard Cross, M.D. 1915-2003 “What is REAL?” asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender before Nana came to tidy the room. “Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?” “Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Audio Describing the Exposition Phase of Films

TRANS · núm. 11 · 2007 La audiodescripción se está introduciendo progresivamente en los productos DOSSIER · 73-93 audiovisuales y esto tiene como resultado por una parte la necesidad de formar a los futuros audiodescriptores y, por otra parte, formar a los formadores con unas herramientas adecuadas para enseñar cómo audiodescribir. No cabe la menor que como documento de partida para la formación las guías y normas de audiodescripción existentes son de una gran utilidad, sin embargo, éstas no son perfectas ya que no ofrecen respuestas a algunas cuestiones esenciales como qué es lo que se debe describir cuando no se cuenta con el tiempo suficiente para describir todo lo que sucede. El presente artículo analiza una de las cuestiones que normalmente no responden las guías o normas: qué se debe priorizar. Se demostrará cómo una profundización en la narrativa de películas y una mejor percepción de las pistas visuales que ofrece el director puede ayudar a decidir la información que se recoge. Los fundamentos teóricos expuestos en la primera parte del artículo se aplicarán a la secuencia expositiva de la película Ransom. PALABRAS CALVE: audiodescripción, accesibilidad, traducción audiovisual. Audio describing the exposition phase of films. Teaching students what to choose Ever more countries are including audio description (AD) in their audiovisual products, which results on the one hand in a need for training future describers and on the other in a need to provide trainers with adequate tools for teaching. Existing AD guidelines are undoubtedly valuable instruments for beginning audio describers, but they are not perfect in that they do not provide answers to certain essential questions, such as what should be described in situations where it is impossible to describe everything that can be seen. -

Pocket Product Guide 2006

THENew Digital Platform MIPTV 2012 tm MIPTV POCKET ISSUE & PRODUCT OFFILMGUIDE New One Stop Product Guide Search at the Markets Paperless - Weightless - Green Read the Synopsis - Watch the Trailer BUSINESSC onnect to Seller - Buy Product MIPTVDaily Editions April 1-4, 2012 - Unabridged MIPTV Product Guide + Stills Cher Ami - Magus Entertainment - Booth 12.32 POD 32 (Mountain Road) STEP UP to 21st Century The DIGITAL Platform PUBLISHING Is The FUTURE MIPTV PRODUCT GUIDE 2012 Mountain, Nature, Extreme, Geography, 10 FRANCS Water, Surprising 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, Delivery Status: Screening France 75019 France, Tel: Year of Production: 2011 Country of +33.1.487.44.377. Fax: +33.1.487.48.265. Origin: Slovakia http://www.10francs.f - email: Only the best of the best are able to abseil [email protected] into depths The Iron Hole, but even that Distributor doesn't guarantee that they will ever man- At MIPTV: Yohann Cornu (Sales age to get back.That's up to nature to Executive), Christelle Quillévéré (Sales) decide. Office: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + GOOD MORNING LENIN ! 33.6.628.04.377. Fax: + 33.1.487.48.265 Documentary (50') BEING KOSHER Language: English, Polish Documentary (52' & 92') Director: Konrad Szolajski Language: German, English Producer: ZK Studio Ltd Director: Ruth Olsman Key Cast: Surprising, Travel, History, Producer: Indi Film Gmbh Human Stories, Daily Life, Humour, Key Cast: Surprising, Judaism, Religion, Politics, Business, Europe, Ethnology Tradition, Culture, Daily life, Education, Delivery Status: Screening Ethnology, Humour, Interviews Year of Production: 2010 Country of Delivery Status: Screening Origin: Poland Year of Production: 2010 Country of Western foreigners come to Poland to expe- Origin: Germany rience life under communism enacted by A tragicomic exploration of Jewish purity former steel mill workers who, in this way, laws ! From kosher food to ritual hygiene, escaped unemployment. -

WHAT YOU NEED to KNOW ABOUT DATING VIOLENCE a TEEN’S HANDBOOK “I Think Dating Violence Is Starting at a Younger Age

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT DATING VIOLENCE A TEEN’S HANDBOOK “I think dating violence is starting at a younger age. It happened to me when I was 14 and I didn’t know what to do. We were friends, and then we started becoming closer. One day, he tried to push himself onto me physically. I didn’t tell anyone for months. I was embarrassed. When I finally told people, the more I talked about it the better I felt. My friend said, ‘You have to remember that you don’t deserve people taking advantage of you.’ A lot of my friends said stuff to him, and it made him feel really stupid about what he had done. The more I talked about it, the more I heard that this stuff happens but it’s not your fault.” — A. R., age 17 table of contents 3 to our teenage friends 4 chapter one: summer’s over 7 chapter two: risky business 10 chapter three: no exit? 14 chapter four: a friend in need 20 chapter five: taking a stand 25 for more information “I’m sorry,” he says, taking her hand. “It’s just that I miss you when you’re not around. I’m sorry I lost my temper.” Excerpted from chapter two. to our teenage friends Your teen years are some of the most exciting and challenging times in your life. You’re meeting new people, forming special friendships and making lifelong decisions. Some of these decisions may involve dating. And while dating can be one of the best things about being a teenager, it brings a host of new feelings and experiences — not all of them good. -

Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 © Copyright by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line by Benjamin Grant Doleac Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair The black brass band parade known as the second line has been a staple of New Orleans culture for nearly 150 years. Through more than a century of social, political and demographic upheaval, the second line has persisted as an institution in the city’s black community, with its swinging march beats and emphasis on collective improvisation eventually giving rise to jazz, funk, and a multitude of other popular genres both locally and around the world. More than any other local custom, the second line served as a crucible in which the participatory, syncretic character of black music in New Orleans took shape. While the beat of the second line reverberates far beyond the city limits today, the neighborhoods that provide the parade’s sustenance face grave challenges to their existence. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina tore up the economic and cultural fabric of New Orleans, these largely poor communities are plagued on one side by underfunded schools and internecine violence, and on the other by the rising tide of post-disaster gentrification and the redlining-in- disguise of neoliberal urban policy. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

2020 Sundance Film Festival: 118 Feature Films Announced

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: December 4, 2019 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2020 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL: 118 FEATURE FILMS ANNOUNCED Drawn From a Record High of 15,100 Submissions Across The Program, Including 3,853 Features, Selected Films Represent 27 Countries Once Upon A Time in Venezuela, photo by John Marquez; The Mountains Are a Dream That Call to Me, photo by Jake Magee; Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, courtesy of Sundance Institute; Beast Beast, photo by Kristian Zuniga; I Carry You With Me, photo by Alejandro López; Ema, courtesy of Sundance Institute. Park City, UT — The nonprofit Sundance Institute announced today the showcase of new independent feature films selected across all categories for the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. The Festival hosts screenings in Park City, Salt Lake City and at Sundance Mountain Resort, from January 23–February 2, 2020. The Sundance Film Festival is Sundance Institute’s flagship public program, widely regarded as the largest American independent film festival and attended by more than 120,000 people and 1,300 accredited press, and powered by more than 2,000 volunteers last year. Sundance Institute also presents public programs throughout the year and around the world, including Festivals in Hong Kong and London, an international short film tour, an indigenous shorts program, a free summer screening series in Utah, and more. Alongside these public programs, the majority of the nonprofit Institute's resources support independent artists around the world as they make and develop new work, via Labs, direct grants, fellowships, residencies and other strategic and tactical interventions.