Female Detainees During the Syrian Revolution:

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

安全理事会 Distr.: General 19 October 2012 Chinese Original: English

联合国 S/2012/515 安全理事会 Distr.: General 19 October 2012 Chinese Original: English 2012年7月2日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信 奉我国政府指示,并继我 2012 年 4 月 16 日至 20 日和 23 日至 25 日、5 月 7 日、11 日、14 日至 16 日、18 日、21 日、24 日、29 日和 31 日、6 月 1 日、4 日、 6 日、7 日、11 日、19 日、20 日、25 日、27 日和 28 日的信,谨随函附上 2012 年 6 月 27 日武装团伙在叙利亚境内违反停止暴力规定行为的详细清单(见附件)。 请将本信及其附件作为安全理事会的文件分发为荷。 常驻代表 大使 巴沙尔·贾法里(签名) 12-56095 (C) 231012 241012 *1256095C* S/2012/515 2012年7月2日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信的附件 [Original: Arabic] Wednesday, 27 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 27 June 2012 at 2200 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a military barracks headquarters in the area of Qastal. 2. At 0200 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement officers in the vicinity of the Industry School in Ra's al-Nab‘, Qatana. 3. At 0630 hours, an armed terrorist group attacked and detonated explosive devices at the Syrian Ikhbariyah satellite channel building in Darwasha in the vicinity of Khan al-Shaykh, killing Corporal Ma'mun Awasu, Conscript Tal‘at al-Qatalji, Conscript Mash‘al al-Musa and Conscript Abdulqadir Sakin. Several employees were also killed, including Sami Abu Amin, Muhammad Shamsah and employee Zayd Ujayl. Another employee was wounded , 11 law enforcement officers were abducted, and 33 rifles were seized. 4. At 0700 hours, an armed terrorist group opened on fire on and fired rocket-propelled grenades at a law enforcement checkpoint in Hurnah between Ma‘araba bridge and Tall. -

Chapter 9 Establishment of the Sewerage Development Master Plan

The study on sewerage system development in the Syrian Arab Republic Final Report CHAPTER 9 ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SEWERAGE DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN 9.1 Basic Condition for Master Plan 9.1.1 Target Year One of Japan’s most highly authoritative design guideline entitled, “Design Guidelines for Sewerage System” prescribes that the target year for a sewerage development plan shall be set approximately 20 years later than the current year. This is due to the following reasons: • The useful life of both the facilities and the construction period should extend over a long period of time; • Of special significance to sewer pipe construction is the phasing of the capacity strengthening. This should be based on the sewage volume increase although this may be quite difficult to track; • Therefore, the sewerage facility plan shall be based on long-term prospect, such as the long-term urbanization plan. In as much as this study started in November 2006, the year 2006 can be regarded as the “present” year. Though 20 years after 2006 is 2026, this was correspondingly adjusted as 2025. Hence, the year 2025 was adopted as target year for this Study. 9.1.2 Sanitation System / Facilities The abovementioned guideline describes “service area” as the area to be served by the sewerage system, as follows: • Since the service area provides the fundamental condition for the sewerage system development plan, investment-wise, the economic and O&M aspects shall be dully examined upon the delineation of the area. • The optimum area, the area where the target pollution reduction can be achieved as stipulated in theover-all development plan, shall be selected carefully. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International Is a Global Movement of More Than 7 Million People Who Campaign for a World Where Human Rights Are Enjoyed by All

‘LEFT TO DIE UNDER SIEGE’ WAR CRIMES AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: MDE 24/2079/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Residents search through rubble for survivors in Douma, Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus. Activists said the damage was the result of an air strike by forces loyal to President Bashar -

PRISM Syrian Supplemental

PRISM syria A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS About PRISM PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners Vol. 4, Syria Supplement on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; 2014 relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development Editor Michael Miklaucic Communications Contributing Editors Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Alexa Courtney communications to: David Kilcullen Nate Rosenblatt Editor, PRISM 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Copy Editors Fort Lesley J. McNair Dale Erikson Washington, DC 20319 Rebecca Harper Sara Thannhauser Lesley Warner Telephone: Nathan White (202) 685-3442 FAX: (202) 685-3581 Editorial Assistant Email: [email protected] Ava Cacciolfi Production Supervisor Carib Mendez Contributions PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Advisory Board and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States Dr. Gordon Adams and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to prism@ Dr. Pauline H. Baker ndu.edu with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador James F. Dobbins without permission of the copyright proprietors. PRISM should be acknowledged whenever material is quoted from or based on its content. -

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

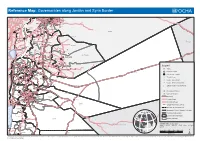

Reference Map: Governorates Along Jordan and Syria Border

Reference Map:] Governorates along Jordan and Syria Border Qudsiya Yafur Tadmor Sabbura Damascus DAMASCUS Obada Nashabiyeh Damascus Maliha Qisa Otayba Yarmuk Zabadin Deir Salman Madamiyet ElshamDarayya Yalda Shabaa Haran Al'awameed Qatana Jdidet Artuz Sbeineh Hteitet Elturkman LEBONAN Artuz Sahnaya Buwayda ] Hosh Sahya Jdidet Elkhas A Tantf DarwashehDarayya Ghizlaniyyeh Khan Elshih Adleiyeh Deir Khabiyeh MqeilibehKisweh Hayajneh Qatana ZahyehTiba Khan Dandun Mazraet Beit Jin Rural Damascus Sa'sa' Hadar Deir Ali Kanaker Duma Khan Arnaba Ghabagheb Jaba Deir Elbakht SYRIA Quneitra Kafr Shams Aqraba Jbab Nabe Elsakher Quneitra As-Sanamayn Hara As-Sanamayn IRAQ Nimer Ankhal Qanniyeh I Jasim Shahba Mahjeh S Nawa Shaqa R Izra' Izra' Shahba Tassil Sheikh Miskine Bisr Elharir A Al Fiq Qarfa Nemreh Abtaa Nahta E Ash-Shajara As-Sweida Da'el Alma Hrak Western Maliha Kherbet Ghazala As-Sweida L Thaala As-Sweida Saham Masad Karak Yadudeh Western Ghariyeh Raha Eastern Ghariyeh Um Walad Bani kinana Kharja Malka Torrah Al'al Mseifra Kafr Shooneh Shamaliyyeh Dar'a Ora Bait Ras Mghayyer Dar'a Hakama ManshiyyehWastiyya Soom Sal Zahar Daraa] Dar'a Tiba Jizeh Irbid Boshra Waqqas Ramtha Nasib Moraba Legend Taibeh Howwarah Qarayya Sammo' Shaikh Hussein Aidoon ! Busra Esh-Sham Arman Dair Abi Sa'id Irbid ] Milh AlRuwaished Salkhad Towns Kofor El-Ma' Nassib Bwaidhah Salkhad Mazar Ash-shamaliCyber City Mghayyer Serhan Mashari'eKora AshrafiyyehBani Obaid ! National Capital Kofor Owan Badiah Ash-Shamaliyya Al_Gharbeh Rwashed Kofor Abiel NULL Ketem ! Jdaitta No'ayymeh -

Forgotten Lives Life Under Regime Rule in Former Opposition-Held East Ghouta

FORGOTTEN LIVES LIFE UNDER REGIME RULE IN FORMER OPPOSITION-HELD EAST GHOUTA A COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE MIDDLE EAST INSTITUTE AND ETANA SYRIA MAY 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-10 CONTENTS * SUMMARY * KEY POINTS AND STATISTICS * 1 INTRODUCTION * 2 MAIN AREAS OF CONTROL * 3 MAP OF EAST GHOUTA * 6 MOVEMENT OF CIVILIANS * 8 DETENTION CENTERS * 9 PROPERTY AND REAL ESTATE UPHEAVAL * 11 CONCLUSION Cover Photo: Syrian boy cycles down a destroyed street in Douma on the outskirts of Damascus on April 16, 2018. (LOUAI BESHARA/AFP/Getty Images) © The Middle East Institute Photo 2: Pro-government soldiers stand outside the Wafideen checkpoint on the outskirts of Damascus on April 3, 2018. (Photo by LOUAI BESHARA/ The Middle East Institute AFP) 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036 SUMMARY A “black hole” of information due to widespread fear among residents, East Ghouta is a dark example of the reimposition of the Assad regime’s authoritarian rule over a community once controlled by the opposition. A vast network of checkpoints manned by intelligence forces carry out regular arrests and forced conscriptions for military service. Russian-established “shelters” house thousands and act as detention camps, where the intelligence services can easily question and investigate people, holding them for periods of 15 days to months while performing interrogations using torture. The presence of Iranian-backed militias around East Ghouta, to the east of Damascus, underscores the extent of Iran’s entrenched strategic control over key military points around the capital. As collective punishment for years of opposition control, East Ghouta is subjected to the harshest conditions of any of the territories that were retaken by the regime in 2018, yet it now attracts little attention from the international community. -

Damascus & Rural Damascus, Syria: Nfi Response

NFI Sector DAMASCUS & RURAL DAMASCUS, SYRIA: NFI RESPONSE Syria Hub Reporting Period: January 2017 CORE SUPPLEMENTARY ± ITEMS ITEMS TOTAL BENEFICIARIES ADEQUATELY SERVED Al-Hasakeh Aleppo Ar-Raqqa Deir Attiyeh 15,000 190,011 Homs PEOPLE WHO RECEIVED MORE THAN 4 CORE NFI PEOPLE WHO RECEIVED AT LEAST 1 SUPPLEMENTA- Idleb ITEMS (.75% OF THE 2.0M PEOPLE IN NEED IN RY ITEM WHICH INCLUDES SEASONAL ITEMS (10% Lattakia DAMASCUS AND RURAL DAMASCUS GOVERNORATES) OF THE 2.0M PEOPLE IN NEED IN DAMASCUS AND RURAL DAMASCUS GOVERNORATES) Hama Deir-ez-Zor TOTAL BENEFICIARIES PER SUB-DISTRICT Tartous An Nabk QATANA 7,500 DAMASCUSE 44,090 Yabroud GHIZLANIYYEH 7,500 KISWEH 28,500 DAMASCUS & RURAL-DAMASCUSHoms JARAMANA 23,750 Esal El-Ward QATANA 18,750 AT-TALL 17,500 Jirud GHIZLANIYYEH 15,417 AZ-ZABDANI 12,500 Damascus Rural Damascus Ma'loula SAHNAYA 11,250 Sarghaya DARIYA 10,000 Quneitra Rankus Raheiba DIMAS 8,255 Dar'a As-Sweida BENEFICIARIES REACHED BY TYPE OF SUPPORT Az-Zabdani Madaya Al Qutayfah ESTIMATE NUMBER OF PERSONS Sidnaya INSIDE DAMASCUS AND RURAL Breakdown of 2 million people 29K DAMASCUS GOVERNORATES WHO 174K in need of NFIs in Damascus RECEIVED IN-KIND ASSISTANCE FROM At Tall IN-KIND ASSISTANCE and Rural Damascus Ein Elfijeh REGULAR PROGRAMMES OF THE IN-KIND ASSISTANCE SECTOR in 2017 per sub-district Qudsiya ESTIMATE NUMBER OF PERSONS 6K 0 - 20,000 Dimas Duma 3K FROM HARD-TO-REACH AND LEBANON BESEIGED AREAS WHO RECEIVED Harasta INTER-AGENCY CONVOY IN-KIND ASSISTANCE THROUGH INTER-AGENCY CONVOY 20,001 - 60,000 INTER-AGENCY CONVOY Damascus Arbin 60,001 - 124,200 DamascusKafr Batna Rural Damascus 9K Jaramana Nashabiyeh 0 ESTIMATE NUMBER OF PERSONS 124,201 - 190,000 WHO RECEIVED CASH ASSISTANCE CASH SUPPORT FROM UNRWA CASH SUPPORT Qatana Markaz Darayya 190,001 - 701,000 Maliha NOTE: Breakdown of beneficiaries per type of support does not necessarily sum up to the reported number of beneficiaries as some communities may have received more than one type of assistance. -

Download S/2013/735

United Nations A/68/663–S/2013/735 General Assembly Distr.: General 13 December 2013 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Sixty-eighth session Sixty-eighth year Agenda item 33 Prevention of armed conflict Identical letters dated 13 December 2013 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the General Assembly and the President of the Security Council I have the honour to convey herewith the final report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic (see annex). I would be grateful if the present final report, the letter of transmittal and its appendices could be brought to the attention of the Members of the General Assembly and of the Security Council. (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 13-61784 (E) 131213 *1361784* A/68/663 S/2013/735 Annex Letter of transmittal Having completed our investigation into the allegations of the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic reported to you by Member States, and further to the report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic (hereinafter, the “United Nations Mission”) on allegations of the use of the chemical weapons in the Ghouta area of Damascus on 21 August 2013 (A/67/997-S/2013/553), we have the honour to submit the final report of the United Nations Mission. To date, 16 allegations of separate incidents involving the use of chemical weapons have been reported to the Secretary-General by Member States, including, primarily, the Governments of France, Qatar, the Syrian Arab Republic, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America.