The Status and the Problem of Western Vocal Music Teaching in Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treble Voices in Choral Music

loft is shown by the absence of the con• gregation: Bach and Maria Barbara were Treble Voices In Choral Music: only practicing and church was not even in session! WOMEN, MEN, BOYS, OR CASTRATI? There were certain places where wo• men were allowed to perform reltgious TIMOTHY MOUNT in a "Gloria" and "Credo" by Guillaume music: these were the convents, cloisters, Legrant in 1426. Giant choir books, large and religious schools for girls. Nuns were 2147 South Mallul, #5 enough for an entire chorus to see, were permitted to sing choral music (obvious• Anaheim, California 92802 first made in Italy in the middle and the ly, for high voices only) among them• second half of the 15th century. In selves and even for invited audiences. England, choral music began about 1430 This practice was established in the with the English polyphonic carol. Middle Ages when the music was limited Born in Princeton, New Jersey, Timo• to plainsong. Later, however, polyphonic thy Mount recently received his MA in Polyphonic choral music took its works were also performed. __ On his musi• choral conducting at California State cue from and developed out of the cal tour of Italy in 1770 Burney describes University, Fullerton, where he was a stu• Gregorian unison chorus; this ex• several conservatorios or music schools dent of Howard Swan. Undergraduate plains why the first choral music in Venice for girls. These schools must work was at the University of Michigan. occurs in the church and why secular not be confused with the vocational con• compositions are slow in taking up He has sung professionally with the opera servatories of today. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

The Performer As Classical Voice Teacher

THE PERFORMER AS CLASSICAL VOICE TEACHER: EVALUATING THE ROLE OF THE PERFORMER-TEACHER AND ITS IMPACT ON THE STUDENT LEARNING EXPERIENCE MARGARET SCHINDLER S368294 QUEENSLAND CONSERVATORIUM GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY in fulfilment of the requirement of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................................... i ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................. iv BOOK CHAPTERS AND PRESENTATIONS ......................................................................................... v STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICITY ...................................................................................................... vi Chapter One: Setting the Scene ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 An auto-ethnography ................................................................................................................ 3 1.3 Rationale for this thesis .......................................................................................................... 10 Chapter Two: -

Headliners 2016 Central Division Conference Special Concerts 2016

2016 Central Division Conference HHeadlinerseadliners Voces8 Ola Gjeilo is the conductor of Voces8. His photo and bio are on page 49. Voces8 is a headliner at this conference. Their photo and bio are on page 49. 2016 Central Division Conference SSpecialpecial CConcertsoncerts Chicago Children’s Choir Medal, which recognizes achievement through research in authorship, in invention, for discovery, for unusual public service or for anything deemed of great benefi t to humanity. In 2012, she received the Roman Nomitch Fel- lowship to attend the Harvard Business School’s Strategic Perspectives in Nonprofi t Management, a program that provides opportunities for senior executives to examine their missions and develop strategies for the new global economy. Lee received a bachelor’s in piano performance from DePaul University and a master’s in conducting from Northwestern University. Founded in 1956 during the height of the Civil Rights Judy Hanson holds a bachelor’s from Movement, Chicago Children’s Choir (CCC) is a non- the University of Illinois and a master’s profi t organization committed to peacefully uniting a from Northwestern University. As direc- diverse world through education, musical expression, and tor of choral programs, Hanson over- excellence. Serving more than 4,000 children annually, sees and directs the coordination and CCC empowers singers to bridge cultural divides and presentation of all Chicago Children’s become ambassadors of peace in their communities. With Choir programs and guides conduc- programs in more than seventy Chicago schools, ten after- tors in serving more than 4,000 children each year. She school neighborhood programs, an ensemble for boys with serves as the associate director and choreographer for the changing voices, and the internationally acclaimed Voice world-renowned Voice of Chicago and the conductor of of Chicago, the diversity of CCC refl ects the cultural DiMension, a choir for young men with changing voices. -

Why Do Singers Sing in the Way They

Why do singers sing in the way they do? Why, for example, is western classical singing so different from pop singing? How is it that Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballe could sing together? These are the kinds of questions which John Potter, a singer of international repute and himself the master of many styles, poses in this fascinating book, which is effectively a history of singing style. He finds the reasons to be primarily ideological rather than specifically musical. His book identifies particular historical 'moments of change' in singing technique and style, and relates these to a three-stage theory of style based on the relationship of singing to text. There is a substantial section on meaning in singing, and a discussion of how the transmission of meaning is enabled or inhibited by different varieties of style or technique. VOCAL AUTHORITY VOCAL AUTHORITY Singing style and ideology JOHN POTTER CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 IRP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1998 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1998 Typeset in Baskerville 11 /12^ pt [ c E] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Potter, John, tenor. -

I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer D. M. A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Yvonne Sellers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Loretta Robinson, Advisor Karen Peeler C. Patrick Woliver Copyright by Crystal Yvonne Sellers 2009 Abstract ―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer With roots in the early songs and Spirituals of the African American slave, and influenced by American Jazz and Blues, Gospel music holds a significant place in the music history of the United States. Whether as a choral or solo composition, Gospel music is accompanied song, and its rhythms, textures, and vocal styles have become infused into most of today‘s popular music, as well as in much of the music of the evangelical Christian church. For well over a century voice teachers and voice scientists have studied thoroughly the Classical singing voice. The past fifty years have seen an explosion of research aimed at understanding Classical singing vocal function, ways of building efficient and flexible Classical singing voices, and maintaining vocal health care; more recently these studies have been extended to Pop and Musical Theater voices. Surprisingly, to date almost no studies have been done on the voice of the Gospel singer. Despite its growth in popularity, a thorough exploration of the vocal requirements of singing Gospel, developed through years of unique tradition and by hundreds of noted Gospel artists, is virtually non-existent. -

A Look at How Vocal Coaching Techniques for Singers Could Be Used to Increase the Effectiveness of Melodic Intonation Therapy on Stroke Patients

A Look at How Vocal Coaching Techniques for Singers Could Be Used to Increase the Effectiveness of Melodic Intonation Therapy on Stroke Patients Eric Dalbey, M.A., B.S., B.A. Dr. Carmen Russell, Ph.D., MS-SLP, CCC • Abstract • 5 Steps of MIT: • Speaking vs. Singing (Jeffries 2004) Although people who suffer strokes can lose the ability to speak, their ability to sing may be retained (Marina 2007). The areas of the brain associated with speaking and singing use an area on the left side of the brain; however, singing also uses frontal parts of the right side of the brain which are unaffected by a left hemisphere stroke affecting speech. Melodic Intonation Therapy is used to exploit this pathway (Schlaug 2010). The overlap between speech and singing can be most easily observed through the shared characteristics of melody (prosody) and rhythm (rate). MIT will use some common words and the clinician will teach the client these phrases by having them sing them while tapping their left hand. The phrases are intoned on just 2 pitches; “melodies” are determined by the phrases’ natural rise and fall of the chosen words. This presentation will compare and contrast the current techniques of teaching MIT against vocal coaching techniques that are normally • Conclusions reserved exclusively for singers. The hope of this exercise is to enrich the current MIT techniques with new ideas that may prove to increase • “MIT in its current form has potential limitations. The first is in the effectiveness and success of this evidence-based strategy to further help use of a small range of pitches, often just two, usually separated by a clients with left hemisphere strokes affecting their speech. -

Vocal-Guide.Pdf

Advice for vocalists and producers for recording vocals A conversation with Jon Marc Weiss, accomplished recording engineer, studio designer, and vocalist. Adele commented on how her pro- You want to have a really good mix for the some experience, you know these things, but ducer got her to sing notes she didn’t vocalist. They need to be able to imagine not when you’re starting out. know she could sing — she was able to their voice in that track. It needs to be sitting Would you say creating a comfortable discover new facets to her voice be- in that track in a place that’s comfortable for environment is important? cause of a producer she obviously them. A lot of engineers won’t put delay or trusted. How do you know how far you reverb on a track until they mix, but with vocals, Yes, absolutely. Sometimes you just have to let you really want it to sound good, you might can push an artist? them know that there’s time, there’s no pres- even want to pick out the reverb you’re going sure and no hurry, and I’m not going to press I think the producer’s experience plays a big to use when you mix, and give the vocalist what record until they’re ready. Of course, a lot of part in this. How many artists they’ve worked they want. When they’re hearing what they times you’re still pressing record to see if you with in their career has a lot to do with their want in the cans, then you’re ready to start the can catch something magical. -

Vocal Techniques for the Instrumentalist

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press NPP eBooks Monographs 2018 Vocal Techniques for the Instrumentalist Amy Rosine Kansas State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks Part of the Higher Education Commons, Music Education Commons, and the Other Music Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Rosine, Amy, "Vocal Techniques for the Instrumentalist" (2018). NPP eBooks. 25. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Monographs at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in NPP eBooks by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOCAL TECHNIQUES FOR THE INSTRUMENTALIST Amy Rosine, D.M.A. 2nd Edition Copyright © 2018 Amy Rosine New Prairie Press Kansas State University Libraries Manhattan, Kansas Cover design by Kansas State University Libraries Background image courtesy of 1014404 Electronic edition available online at http://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/ This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-ShareAlike License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ ISBN-13: 978-1-944548-19-3 Contents Introduction 2 Chapter 1 Why are you here? 3 Chapter 2 Healthy Singing 6 Chapter 3 Motivation 9 Chapter 4 Learning and Performing Vocal Music 11 Chapter 5 Respiration 13 Chapter 6 Phonation 15 Chapter 7 Voice Range 19 Chapter 8 Resonance 22 Chapter 9 Articulation 26 Bibliography 34 Appendix A Vocal Exercises i Appendix B Practice Log ii Appendix C Glossary iii Appendix D Italian IPA iv About the Author Vocal techniques for the instrumentalist 1 Introduction Heathy vocal production is necessary for everyone in the teaching field. -

On Being an Opera / Vocal Coach…. - O Resta C Ybriwsky

ON BEING AN OPERA / VOCAL COACH…. - O RESTA C YBRIWSKY. M ARCH 2007 It is a rare thing for a pianist who loves voice to remain being “just a pianist”. The more a pianist grows artistically and personally, the more his* own working sphere widens and deepens. On the way to earning a living with the piano, some pianists will land as opera coaches. To me, there really is no great difference between an opera coach and an “accompanist”, only in what is expected of each. Both love vocal music, the voice (we hope!), and both support the singer – one is on stage, the other off-stage. A singer will not and should not refrain from asking his pianist for feedback, suggestions, and guidance. It is expected of an opera coach. Of course the repertoire of each differs considerably, but any first-class musician will be familiar with a wide- range of repertoire, extending beyond opera to Art song, Oratorio and various other genres. If we are speaking specifically of opera coaching, a pianist has to know the repertoire well enough to guide a singer in the style, the tempi, the general musical execution of the opera and its traditions. Knowing when to give a singer a bit of extra time for a high or even low note, when to manoeuvre or just remain in tempo – many of these things depend not only on the acquaintance with an opera or its stylistic requirements, but also with the orchestral score. Ideally, an opera coach needs to have good vocal judgement about voice production, including essential listening abilities for intonation, foreign language pronunciation and for diction, as well as a commendable musical instinct. -

Private Voice Lessons at Singers Unlimited 8699 Highland Drive • Sandy, Utah Vocal Coach: Eric Richards • 801.654.3742

Private voice lessons at Singers Unlimited 8699 Highland Drive • Sandy, Utah Vocal Coach: Eric Richards • 801.654.3742 THE SLS TECHNIQUE: Speech Level Singing was developed by Seth Riggs of Los Angeles, California and it is the foundation on which over 120 Grammy award winners, four metropolitan opera winners, and countless Broadway stars and major motion picture and television personalities have built their careers. This is the technique David Archuleta studied locally in Salt Lake. Seth Riggs is considered the entertainment world's top vocal instructor. This technique is a way of using your voice that allows you to sing freely and clearly anywhere in your range, with all of your words clearly understood. Since you are not learning what to sing, but rather how to sing, you can apply this technique to any type of music. Singing is a natural process. The technique I teach is very much about freeing the instrument, finding each singer's sound, and removing excess tensions we all carry that keep us from singing easily and at our best. Speech Level Singing even rehabilitates vocal damage resulting from years of misuse or poor teaching. VOCAL TUITION OPTIONS: All tuition is flat fee based. The monthly tuition rate covers the many extra hours I spend on recitals, planning group sessions, certification, and volunteering and participating in vocal and music associations so that my students can participate in activities such as SLS Master workshops and competitions. Monday – Friday Sessions: $125 monthly fee Includes weekly 30-minute private lessons and 1 group artist development session – monthly sign up sheet (typically end of the month). -

How to Request a Regular Vocal Coach Fall 2020

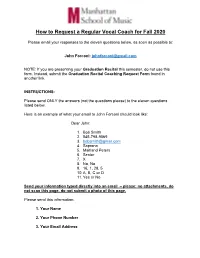

How to Request a Regular Vocal Coach for Fall 2020 Please email your responses to the eleven questions below, as soon as possible to: John Forconi: [email protected] NOTE: If you are presenting your Graduation Recital this semester, do not use this form. Instead, submit the Graduation Recital Coaching Request Form found in another link. INSTRUCTIONS: Please send ONLY the answers (not the questions please) to the eleven questions listed below. Here is an example of what your email to John Forconi should look like: Dear John: 1. Bob Smith 2. 545-798-9069 3. [email protected] 4. Soprano 5. Maitland Peters 6. Senior 7. X 8. No, No 9. 16, 1, 28, 5 10. A, B, C or D 11. Yes or No Send your information typed directly into an email – please: no attachments, do not scan this page, do not submit a photo of this page. Please send this information: 1. Your Name 2. Your Phone Number 3. Your Email Address 4. Your Voice Category: whether Soprano, Mezzo, Tenor, Countertenor, Baritone, or Bass 5. Your Major Teacher 6. Your Status: Fresh, Soph, Junior, Senior, Diploma, Masters-1, Masters-2, Postgraduate Diploma, Professional Studies, or Doctoral 7. If you have a Junior Status: When are you presenting your Junior Half- Recital? NOTE: You must have one before sending in the information on this questionnaire. 8. Are you a full-time student (12 credit hours or more)? Please answer Yes, or No. If you are not a full-time student, are you taking voice lessons for credit? Please answer Yes, or No 9.