El Bildungsroman En El Caribe Hispano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Senado De Puerto Rico Diario De Sesiones Procedimientos Y Debates De La Decimocuarta Asamblea Legislativa Quinta Sesion Ordinaria Año 2003 Vol

SENADO DE PUERTO RICO DIARIO DE SESIONES PROCEDIMIENTOS Y DEBATES DE LA DECIMOCUARTA ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA QUINTA SESION ORDINARIA AÑO 2003 VOL. LII San Juan, Puerto Rico Jueves, 20 de marzo de 2003 Núm. 21 A la una y dieciocho minutos de la tarde (1:18 p.m.) de este día, jueves, 20 de marzo de 2003, el Senado reanuda sus trabajos bajo la Presidencia del señor Antonio J. Fas Alzamora. ASISTENCIA Senadores: Modesto L. Agosto Alicea, Luz Z. Arce Ferrer, Eudaldo Báez Galib, Norma Burgos Andújar, Juan A. Cancel Alegría, José Luis Dalmau Santiago, Velda González de Modestti, Sixto Hernández Serrano, Rafael L. Irizarry Cruz, Pablo Lafontaine Rodríguez, Fernando J. Martín García, Kenneth McClintock Hernández, Yasmín Mejías Lugo, José Alfredo Ortiz-Daliot, Margarita Ostolaza Bey, Migdalia Padilla Alvelo, Orlando Parga Figueroa, Sergio Peña Clos, Roberto L. Prats Palerm, Miriam J. Ramírez, Bruno A. Ramos Olivera, Jorge Alberto Ramos Vélez, Cirilo Tirado Rivera, Roberto Vigoreaux Lorenzana y Antonio J. Fas Alzamora, Presidente. SR. PRESIDENTE: Se reanuda la Sesión. INVOCACION La senadora Migdalia Padilla Alvelo, procede con la Invocación. SRA. PADILLA ALVELO: En tono de reverencia, vamos en la tarde de hoy a invocar la presencia del Señor ante este honorable Cuerpo: "La tempestad calmada. Un día subió Jesús a una barca con sus discípulos. Les dijo: “Pasemos a la otra orilla del lago” y ellos remaron mar adentro. Mientras navegaban, Jesús se durmió. De repente una tempestad se desencadenó sobre el lago, y la barca se fue llenando de agua a tal punto que peligraban. Se acercaron a El y lo despertaron. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Spanish Karaoke DVD/VCD/CDG Catalog August, 2003

AceKaraoke.com 1-888-784-3384 Spanish Karaoke DVD/VCD/CDG Catalog August, 2003 Version) 03. Emanuel Ortega - A Escondidas Spanish DVD 04. Jaci Velasquez - De Creer En Ti 05. El Coyote Y Su Banda Tierra Santa - Sufro 06. Liml - Y Dale Fiesta Karaoke DVD Vol.1 07. Mana - Te Solte La Rienda ID: SYOKFK01SK $Price: 22 08. Marco Antonio Solis - El Peor De Mis Fracasos Fiesta Karaoke DVD Vol.1 09. Julio Preclado Y Su Banda Perla Del Pacifico - Me 01. Enrique Iglesias - Nunca?Te Ol Vidare Caiste Del?Cielo 02. Shakira - Inevitable 10. Limite - Acariciame 03. Luis Miguel - Dormir Contigo 11. Banda Maguey - Dos Gotas De Agua 04. Victor Manuelle?- Pero Dile 12. Milly Quezad - Pideme 05. Millie - De Hoy En Adelante 13. Diego Torres - Que Sera 06. Tonny Tun Tun - Cuando La Brisa Llega 14. La Puerta 07. Enrique Iglesias - Solo Me Importas Tu (Be With 15. Victor Manuelle - Como Duele You) 16. Micheal Stuart - Casi Perfecta 08. Azul Azul - La Bomba 09. Banda Manchos - En Toda La Chapa Fiesta Karaoke DVD Vol.4 10. Los Tigres Del Norie - De Paisano ID: SYOKFK04SK $Price: 22 11. Limite21 - Estas?Enamorada Fiesta Karaoke DVD Vol. 4 12. Intocahie - Ya Estoy Cansado 01. Ricky Martin - The Cup Of Life 13. Conjunto Primavera - Necesito Decirte 02. Chayanne - Dejaria Todo 14. El Coyote Y Su Banda Tierra Santa - No Puedo Ol 03. Tito Nie Ves - Le Gusta Que La Vean Vidar Tu Voz 04. El Poder Del North - A Ella 15. Joan Sebastian - Secreto De Amor 05. Victor Manuelle - Si La Ves 16. -

Comite Noviembre Comite

Digital Design by Maria Dominguez 2016 © Digital Design by Maria Dominguez 2016 © 2016 2016 CALENDAR JOURNAL CALENDAR JOURNAL COMITÉ NOVIEMBRE NOVIEMBRE COMITÉ COMITÉ NOVIEMBRE NOVIEMBRE COMITÉ CALENDAR JOURNAL CALENDAR PUERTO RICAN HERITAGE MONTH RICAN HERITAGE PUERTO PUERTO RICAN HERITAGE MONTH RICAN HERITAGE PUERTO “irty years of impact on the Puerto Rican Community... “irty of impact on the Puerto years “irty years of impact on the Puerto Rican Community... “irty of impact on the Puerto years mes de la herencia puertorriqueña mes de la herencia Treinta años de impacto a la comunidad puertorriqueña...” Treinta comite noviembre comite mes de la herencia puertorriqueña mes de la herencia Treinta años de impacto a la comunidad puertorriqueña...” Treinta comite noviembre comite 30th Anniversary 30th Anniversary Congratulations to Comite Noviembre on the 30th Anniversary of Puerto Rican Heritage Month! Thank you for your work supporting our children and families. To schedule a free dental van visit in your community, or to learn more about the Colgate® Bright Smiles, Bright Futures™ program, visit our website at www.colgatebsbf.com. COMITÉ NOVIEMBRE Would Like To Extend Its Sincerest Gratitude To The Sponsors And Supporters Of Puerto Rican Heritage Month 2016 City University of New York Hispanic Federation Colgate-Palmolive Company Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center Bronx Community College, CUNY The Nieves Gunn Charitable Fund Brooklyn College, CUNY 32BJ SEIU Compañia de Turismo de Puerto Rico United Federation of Teachers Rums of Puerto Rico Hostos Community College, CUNY Shape Magazine Catholic Charities of New York Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, Hunter College, CUNY Mr. -

Senado De Puerto Rico Diario De Sesiones Procedimientos Y Debates De La Duodecima Asamblea Legislativa Quinta Sesion Ordinaria Año 1995

SENADO DE PUERTO RICO DIARIO DE SESIONES PROCEDIMIENTOS Y DEBATES DE LA DUODECIMA ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA QUINTA SESION ORDINARIA AÑO 1995 VOL. XLVI San Juan, Puerto Rico Jueves, 15 de junio de 1995 Núm. 50 A la una y treinta y tres minutos de la tarde (1:33 p.m.), de este día, jueves, 15 de junio de 1995, el Senado reanuda sus trabajos bajo la Presidencia del señor Roberto Rexach Benítez, Presidente. ASISTENCIA Senadores: Eudaldo Báez Galib, Rubén Berríos Martínez, Norma L. Carranza De León, Antonio J. Fas Alzamora,Velda González de Modestti, Roger Iglesias Suárez, Luisa Lebrón Vda. de Rivera, Miguel A. Loiz Zayas, Víctor Marrero Padilla, Aníbal Marrero Pérez, Kenneth McClintock Hernández, José Enrique Meléndez Ortiz, Luis Felipe Navas de León, Nicolás Nogueras, Hijo; Mercedes Otero de Ramos, Sergio Peña Clos, Oreste Ramos, Marco Antonio Rigau, Ramón L. Rivera Cruz, Charlie Rodríguez Colón, Rafael Rodríguez González, Enrique Rodríguez Negrón, Rolando A. Silva, Cirilo Tirado Delgado, Freddy Valentín Acevedo, Dennis Vélez Barlucea, Eddie Zavala Vázquez y Roberto Rexach Benítez, Presidente. SR. PRESIDENTE: Se reanuda la sesión. INVOCACION El Padre José Rivas y el Reverendo David Casillas, miembros del Cuerpo de Capellanes del Senado de Puerto Rico, proceden con la Invocación. PADRE RIVAS: Puestos en la Presencia del Señor, hoy que celebramos una fiesta especial, la Fiesta del Cuerpo y la Sangre de Cristo que se da con nosotros y se queda con nosotros. Meditamos del Evangelio de San Mateo, Capítulo 5: "Ustedes son la sal de este mundo, pero si la sal deja de estar salada, ¿cómo podrá recobrar su sabor? Ya no sirve para nada, así que se le tira a la calle y la gente la pisotea. -

Senado De Puerto Rico Diario De Sesiones Procedimientos Y Debates De La Decimosexta Asamblea Legislativa Tercera Sesion Ordinaria Año 2010 Vol

SENADO DE PUERTO RICO DIARIO DE SESIONES PROCEDIMIENTOS Y DEBATES DE LA DECIMOSEXTA ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA TERCERA SESION ORDINARIA AÑO 2010 VOL. LVIII San Juan, Puerto Rico Lunes, 3 de mayo de 2010 Núm. 26 A la una y veintidós minutos de la tarde (1:22 p.m.) de este día, lunes, 3 de mayo de 2010, el Senado inicia sus trabajos bajo la Presidencia del señor Thomas Rivera Schatz. ASISTENCIA Senadores: Roberto A. Arango Vinent, Luis A. Berdiel Rivera, Norma E. Burgos Andújar, José L. Dalmau Santiago, José R. Díaz Hernández, Alejandro García Padilla, Héctor Martínez Maldonado, Angel Martínez Santiago, Migdalia Padilla Alvelo, Kimmey Raschke Martínez, Carmelo J. Ríos Santiago, Luz M. Santiago González, Lawrence Seilhamer Rodríguez, Lornna J. Soto Villanueva, Jorge I. Suárez Cáceres, Cirilo Tirado Rivera, Carlos J. Torres Torres, y Thomas Rivera Schatz, Presidente. SR. PRESIDENTE: Habiendo el quórum requerido, continuamos con los trabajos. (Se hace constar que después del Pase de Lista Inicial entraron a la Sala de Sesiones: la señora Luz Z. Arce Ferrer; los señores Eduardo Bhatia Gautier, Antonio J. Fas Alzamora; la señora Sila María González Calderón; el señor Juan E. Hernández Mayoral; la señora Margarita Nolasco Santiago; el señor Eder E. Ortiz Ortiz; las señoras Itzamar Peña Ramírez, Melinda K. Romero Donnelly; el señor Antonio Soto Díaz; y la señora Evelyn Vázquez Nieves). INVOCACION El Reverendo Juan Ramón Rivera y el Padre Efraín López Sánchez, miembros del Cuerpo de Capellanes del Senado de Puerto Rico, proceden con la Invocación. REVERENDO RIVERA: Oramos. Soberano Dios, Padre nuestro, cuán grande es tu Nombre en toda la tierra. -

Visual Foxpro

THE LATIN ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. FINAL NOMINATIONS 9th Annual Latin GRAMMY ® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year July 1, 2007 through June 30, 2008 The following information is confidential and is not to be copied, loaned or otherwise distributed. ACADEMIA LATINA DE ARTES Y CIENCIAS DE LA GRABACION, INC. LISTA FINAL DE NOMINACIONES 9a. Entrega Anual del Latin GRAMMY ® Para grabaciones lanzadas durante el año de elegibilidad 1° de julio del 2007 al 30 de junio del 2008 La siguiente información es confidencial y no debe ser copiada, prestada o distribuida de ninguna forma ACADEMIA LATINA DAS ARTES E CIÊNCIAS DA GRAVAÇÃO, INC. LISTA FINAL DOS INDICADOS 9 a Entrega Anual do Latin GRAMMY® Para gravações lançadas durante o Ano de Elegibilidade 1° de julho de 2007 a 30 de junho de 2008 As informações aqui contidas são confidenciais e não devem ser copiadas, emprestadas ou distribuídas por nenhum meio General Field Category 1 Category 2 Record Of The Year Album Of The Year Grabación Del Año Album Del Año Gravação Do Ano Álbum Do Ano Award to the Artist and to the Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s) Award to the Artist(s), and to the Album Producer(s), Recording and/or Mixer(s) if other than the artist. Engineer(s) / Mixer(s) & Mastering Engineer(s) if other than the artist. Premio al Artista(s), Productor(es) del Album y al Ingeniero(s) de Grabación. Premio al Artista(s), Productor(es) del Album y al Ingeniero(s) de Prêmios ao(s) Artista(s), Produtor(es) do Álbum e Engenheiro(s) de Grabación, Ingeniero(s) de Mezcla y Masterizadores, si es(son) otro(s) Gravação. -

Los-Once-De-La-Tribu.Pdf

LOS ONCE DE LA TRIBU Juan Villoro © Juan Villoro Octubre 2017 Descarga gratis éste y otros libros en formato digital en: www.brigadaparaleerenlibertad.com Cuidado de la edición: Alicia Rodríguez. Diseño de interiores y portada: Daniela Campero. @BRIGADACULTURAL ESCRIBIR AL SOL n 1979 era guionista del programa de radio El lado oscu- Ero de la luna y fui invitado por Huberto Batís y Fernan- do Benítez a escribir crítica de rock en el suplemento sábado, de unomásuno. Con célebre indulgencia, Batís y Benítez fin- gieron no advertir que su presunto crítico se apartaba del tema y, en muchas ocasiones, de la realidad. Así se inició mi trayectoria por las aguas de la crónica. El principal beneficio fue compensar la soledad de escribir fic- ción. Uno de los misterios de lo “real” es que ocurre lejos: hay que atravesar la selva en autobús en pos de un líder guerrillero o ir a un hotel de cinco estrellas para conocer a la luminaria escapada de la pantalla. En sus llamadas, los jefes de redacción prometen mucha posteridad y poco di- nero. Ignoran su mejor argumento: salir al sol. Este libro es una selección de las crónicas que he escrito en los últimos ocho años. Comienza con un texto sobre el descubrimiento de la vocación por la lectura, los demás, aspiran a poner en práctica esa pasión. A tres décadas de que Tom Wolfe asaltó el cielo de las im- prentas con sus quíntuples signos de admiración, la mez- cla de recursos del periodismo y la literatura es ya asunto canónico; a nadie asombra la combinación de datos docu- mentales con el punto de vista subjetivo del narrador; el criterio de veracidad, sin embargo, es un ingrediente miste- rioso: una de las crónicas más testimoniales (“Extraterres- tres en amplitud modulada”) tiene un tono enrarecido, y la más delirante (“Monterroso, libretista de ópera”) merecería ser cierta. -

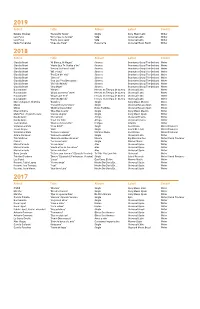

Discography from Website

2019 Artist Title Album Label Credit Natalia Jiménez "Nunca Es Tarde" Single Sony Music Latin Writer Luis Fonsi "Dime que no te iras" Vida Universal Latin Writer Luis Fonsi "Tanto para nada" Vida Universal Latin Writer Paula Fernandes "Chao de Areia" Hora Certa Universal Music Brazil Writer 2018 Artist Title Album Label Credit Claudia Brant "Ni Blanco, Ni Negro" Sincera Brantones/Sony/The Orchard Writer Claudia Brant "Hasta Que Te Vuelva a Ver" Sincera Brantones/Sony/The Orchard Writer Claudia Brant "Piensa Un Poco En Mi" Sincera Brantones/Sony/The Orchard Writer Claudia Brant "Mil e Uma" Sincera Brantones/Sony/The Orchard Writer Claudia Brant "Por Eso Me Voy" Sincera Brantones/Sony/The Orchard Writer Claudia Brant "Sincera" Sincera Brantones/Sony/The Orchard Writer Claudia Brant "Con Los Pies Descalzos" Sincera Brantones/Sony/The Orchard Writer Claudia Brant "Vivir Sin Miedo" Sincera Brantones/Sony/The Orchard Writer Claudia Brant "Una Mujer" Sincera Brantones/Sony/The Orchard Writer Bustamante "Heroes" Heroes en Tiempo de Guerra Universal Latin Writer Bustamante "Ahora que eres Fuerte" Heroes en Tiempo de Guerra Universal Latin Writer Bustamante "Desde que te vi" Heroes en Tiempo de Guerra Universal Latin Writer Bustamante "Vivir Sin Miedo" Heroes en Tiempo de Guerra Universal Latin Writer Noel Schajris ft. El Micha "Bandera” Single Sony Music Mexico Writer Morat "Yo no Merezco Volver" Single Universal Music Spain Writer Morat "Maldita Costumbre" Balas Perdidas Universal Music Spain Writer Noel Schafris "Mas Que Suerte" Single Sony Music