Libya: Actual Or Perceived Supporters of Former President Gaddafi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

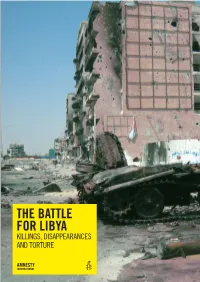

The Battle for Libya

THE BATTLE FOR LIBYA KILLINGS, DISAPPEARANCES AND TORTURE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2011 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2011 Index: MDE 19/025/2011 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo : Misratah, Libya, May 2011 © Amnesty International amnesty.org CONTENTS Abbreviations and glossary .............................................................................................5 Introduction .................................................................................................................7 1. From the “El-Fateh Revolution” to the “17 February Revolution”.................................13 2. International law and the situation in Libya ...............................................................23 3. Unlawful killings: From protests to armed conflict ......................................................34 4. -

Alternatif Politika Is Devoted to the Arab Revolts of 2011 –The Series of Dynamic Social and Political Developments Not Seen in the Arab World for Over Fifty Years

alternatif politika Cilt 3, Sayı 3, Kasım 2011 Misafir Editör: Prof. Bogdan SZAJKOWSKİ Timeline of the Arab Revolt: December 2010-June 2011 Bogdan SZAJKOWSKİ Social Media Tools and the Arab Revolts Bogdan SZAJKOWSKİ The Social Opposition Movement in Syria: The Assad Regime in the Context of Reform and Revolution Veysel AYHAN European Union’s Ineffective Middle East Policy Revealed after Revolution in Tunisia Bahar Turhan HURMİ Libyan Uprising And International Intervention: NATO’s Mission and Libya’s Gridlock Veysel AYHAN Arab Spring and Israeli Security: The New Threats Dünya BAŞOL Background of the Tunisian Revolution Nebahat TANRIVERDİ alternatif politika Cilt 3, Sayı 3, Kasım 2011 Introduction- Bogdan SZAJKOWSKİ, i-ii. Timeline of the Arab Revolt: December 2010 – June 2011- Bogdan SZAJKOWSKİ, 256-419. Social Media Tools and the Arab Revolts-Bogdan SZAJKOWSKİ, 420-432. The Social Opposition Movement in Syria: The Assad Regime in the Context of Reform and Revolution-Veysel AYHAN, 433- 454. European Union’s Ineffective Middle East Policy Revealed after Revolution in Tunisia-Bahar Turhan HURMİ, 455-489. Libyan Uprising And International Intervention: NATO’s Mission and Libya’s Gridlock-Veysel AYHAN, 490-508. Arab Spring and Israeli Security: The New Threats-Dünya BAŞOL, 509-546. Background of the Tunisian Revolution-Nebahat TANRIVERDİ, 547-570. INTRODUCTION Guest Editor: Prof. Bogdan Szajkowski This special issue of Alternatif Politika is devoted to the Arab revolts of 2011 –the series of dynamic social and political developments not seen in the Arab world for over fifty years. Throughout 2011 the Middle East, the Gulf region, Arab Peninsula and North Africa have witnessed social and political turmoil that has fundamentally impacted not only on these regions but also on the rest of the world. -

Militants in Libyan Politics a Militant Leadership Monitor Special Report Recovering from Several Decades of Gaddafi’S Rule

Election Issue: Militants in Libyan Politics A Militant Leadership Monitor Special Report Recovering From Several Decades of Gaddafi’s Rule Quarterly Special Report u July 2012 A Focus on the Role of Militants in Libyan Politics The Libyan PoLiTicaL LandscaPe: beTween LocaL FragmenTaTion and naTionaL democraTic ambiTions by dario cristiani ......................................................................................................................................2 emerging Leaders in Libya: jihadisTs resorTing To PoLiTics To creaTe an isLamic sTaTe by camille Tawil .......................................................................................................................................6 From miLiTia Leader To deFense minisTer: a biograPhicaL skeTch oF osama aL-juwaLi Belhadj: one of many militant leaders by dario cristiani .....................................................................................................................................9 who participated in the Libyan elections The ideoLogicaL inFLuence oF “The bLind sheikh” omar abdeL rahman on Libyan miLiTanTs Militant Leadership Monitor, the by michael w. s. ryan ...........................................................................................................................10 Jamestown Foundation’s premier subscription-based publication, The ZinTan miLiTia and The FragmenTed Libyan StaTe allows subscribers to access by dario cristiani ....................................................................................................................................13 -

Dignity and Dawn: Libya's Escalating Civil

Dignity and Dawn: Libya’s Escalating Civil War Daveed Gartenstein-Ross & Nathaniel Barr ICCT Research Paper February 2015 This report provides a detailed examination of the armed conflict in Libya between the Operation Dignity and Libya Dawn military coalitions. The conflict erupted in May 2014, when Dignity leader Khalifa Hifter announced the launch of his campaign, which was aimed at ridding eastern Libya of Islamist militias, beginning with Benghazi. This offensive shattered a fragile status quo. Revolutionary forces concentrated in the city of Misrata and Islamist politicians perceived Hifter’s offensive as a direct affront and, following parliamentary elections that these factions lost, the Misrata-Islamist bloc announced the launch of the Libya Dawn offensive, aimed at driving pro-Dignity forces out of Tripoli. More broadly, the Dawn offensive was an effort to change facts on the ground in order to ensure that the Misrata-Islamist bloc retained political influence. The Dignity and Dawn offensives have contributed to the continuing political and geographic fragmentation of Libya. Libya now has two separate parliaments and governments, while much of the country has been carved into spheres of influence by warring factions. The Dignity-Dawn conflict has also caused a deterioration of security, which has played into the hands of a variety of violent non-state actors, including al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates that have capitalised on Libya’s security vacuum to establish bases of operation. This report provides a blow-by-blow account of the military conflict between Dignity and Dawn forces, then assesses the implications of the Libyan civil war on regional security and potential policy options for Western states. -

Libya: Country Report Situa�On in Libya

Asylum Research Centre Libya: Country Report Situa�on in Libya /shutterstock.com Miro Novak 5 July 2013 Cover photo © ` 5th July 2013 Libya Country Report Commissioned by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. Any views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of UNHCR. Explanatory Note Sources and Databases Consulted List of Acronyms CONTENTS 1. Background Information 1.1 Geographical Information 1.1.1 Libya’s three distinct parts: Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and Fezzan 1.1.2 Libya’s rate of population growth; population disparity between young and old 1.2 Ethnic Groups 1.3 Geographic and Tribal Issues 1.3.1 Main Tribes 1.3.2 Gaddafi policy toward the East 1.3.3 Geographical divisions during 2011 uprising 1.4 Islamism 1.4.1 Salafism Movement 1.4.2 Current Islamic Opposition Groups 1.4.2.1 Libyan Islamic Group 1.4.2.2 Libyan Islamic Fighting Group 2. Main Political Developments following the death of Gaddafi 2.1 National Transitional Council 2.2 July 2012 Election and General National Congress 2.3 General National Congress Political Parties: Homeland Party, Justice and Construction Party, National Centrist Party, National Forces Alliance, National Front Party 3 Security Situation since the formation of the National Transitional Council 3.1 Gaddafi’s security forces during and after the 2011 uprising 3.1.1 Attacks against former Gaddafi supporters following 2011 uprising 3.2 Attack on US Consulate, Benghazi 3.2.1 Attacks on vehicles carrying the Italian consul 3.2.2 3.2.2 Attack on French Embassy 3.3 Violence in Benghazi in May and June 2013 3.4 Tribal Clashes 3.4.1 Fighting in Bani Walid 3.4.2 Fighting around Kufra and Sebha This document is intended to be used as a tool to help to identify relevant COI and the COI referred to in this report can be considered by decision makers in assessing asylum applications and appeals. -

Final Report: General National Congress Elections in Libya, July 7, 2012

General National Congress Elections in Libya Final Report July 7, 2012 Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. The Carter Center strives to relieve suffering by advancing peace and health worldwide; it seeks to prevent and resolve conflicts, enhance freedom and democracy, and protect and promote human rights worldwide. General National Congress Elections in Libya Final Report July 7, 2012 One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................2 Election Day ..............................38 Executive Summary .........................4 Opening ................................38 The Carter Center and the GNC Elections ......4 Polling .................................40 Pre-election Developments ...................4 Closing .................................42 Polling and Postelection Developments ..........6 Postelection Developments ..................43 Recommendations ..........................7 Vote Counting and Tabulation ...............43 The Carter Center in Libya...................8 Election Results ..........................45 Election Observation Methodology .............9 Al Kufra .................................46 Historical and Political Background ...........11 Out-of-Country Voting .....................48 The Sanusi Monarchy: Federalism Versus Conclusions and Recommendations . .49 a Unitary State, 1951–1969 ................11 To the Government of Libya ................50 The Qadhafi Period, 1969–2011 -

Research Notes

Number 22 — August 2014 RESEARCH NOTES THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY KHALIFA HAFTAR: Rebuilding Libya from the Top Down Barak Barfi N MAY 16, 2014, Libyan general Khalifa Haf- Although Haftar’s campaign poses risks to Lib- tar launched Operation Dignity “in order to ya’s nascent democracy, allowing the government to Oeliminate the extremist terrorist” groups that have neglect the country is an even greater threat to its been destabilizing the country.1 He had been plan- well-being. The challenge facing Washington and ning the campaign for two years, first stumping for a its allies lies in balancing Haftar’s aspirations against revamped army and only later attacking the govern- the need to nurture a pluralistic state. By supporting ment for its inertia and ties to Islamists. Operation Dignity while also promoting democratic Many had written him off as a disgruntled officer of reform and building state institutions, the United the ancien régime in a new arena populated by revolu- States can help Libya emerge from the crisis gripping tionaries. A divisive figure, he never won sufficient -sup the country. Examining Haftar’s life will better allow port from Libyans during the 2011 revolution to have policymakers to understand the lurking pitfalls inher- the prominent role he felt was naturally his due, though, ent in his movement while highlighting its potential as discussed later, in 2011 he did win some significant to extract Libya from the morass. support. Some mistrusted his ties to former leader WHO IS KHALIFA HAFTAR? Muammar Qadhafi, which stretch back to the 1960s.