(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Public Rights of Way and Greens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

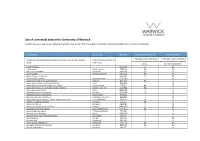

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick Please Use

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick Please use the table below to check whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for a contextual offer. For more information about our contextual offer please visit our website or contact the Undergraduate Admissions Team. School Name School Postcode School Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school which meets the 'Y' indicates a school which meets the Free School Meal criteria. Schools are listed in alphabetical order. school performance citeria. 'N/A' indicates a school for which the data is not available. 6th Form at Swakeleys UB10 0EJ N Y Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School ME2 3SP N Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST2 8LG Y Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton TS19 8BU Y Y Abbey School, Faversham ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent DE15 0JL Y Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool L25 6EE Y Y Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Y N Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge UB10 0EX Y N School Name School Postcode School Performance Free School Meals Abbs Cross School and Arts College RM12 4YQ Y N Abbs Cross School, Hornchurch RM12 4YB Y N Abingdon And Witney College OX14 1GG Y NA Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Y Y Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Y Y Abraham Moss High School, Manchester M8 5UF Y Y Academy 360 SR4 9BA Y Y Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Y Y Acklam Grange -

Inspector's Report: Stoke Lodge Playing Field

Original Names Redacted for Publication Purposes APPLICATION BY MR DAVID MAYER TO REGISTER LAND KNOWN AS STOKE LODGE PLAYING FIELD, SHIREHAMPTON ROAD, BRISTOL, AS A NEW TOWN OR VILLAGE GREEN REPORT Preliminary 1. Bristol City Council is the statutory body charged by statute with maintaining the register of village greens. It has asked me to advise it whether land within its area known as Stoke Lodge Playing Field should be registered as a town or village green. I am a barrister in private practice with expertise in the law of town and village greens. In this capacity, I have often advised registration authorities and have often acted on their behalf as an Inspector, holding a public inquiry into an application before reporting and making a recommendation. I have also often advised and acted for applicants who have sought to register land as a town or village green; and for objectors, who have argued that land should not be registered as a town or village green. Procedural history 2. On 7 March 2011, David Mayer on behalf of Save Stoke Lodge Parkland made an application to register land at Stoke Lodge Playing Field/Parkland, Shirehampton Road, Bristol (“the application site”) as a town or village green. Objections to the application were received from Bristol City Council in its capacity as landowner (the First Objector), the University of Bristol (the Second Objector), Rockleaze Rangers Football Club (the Third Objector) and Cotham School (the Fourth Objector). Mr Mayer responded to those objections and subsequently there were further exchanges of representations. In its capacity as registration authority the City Council initially considered that it would be necessary for there to be a non-statutory public inquiry and, on this basis, invited me to hold such an inquiry1. -

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick The data below will give you an indication of whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for the contextual offer at the University of Warwick. School Name Town / City Postcode School Exam Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school with below 'Y' indcicates a school with above Schools are listed on alphabetical order. Click on the arrow to filter by school Click on the arrow to filter by the national average performance the average entitlement/ eligibility name. Town / City. at KS5. for Free School Meals. 16-19 Abingdon - OX14 1RF N NA 3 Dimensions South Somerset TA20 3AJ NA NA 6th Form at Swakeleys Hillingdon UB10 0EJ N Y AALPS College North Lincolnshire DN15 0BJ NA NA Abbey College, Cambridge - CB1 2JB N NA Abbey College, Ramsey Huntingdonshire PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School Medway ME2 3SP NA Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College Stoke-on-Trent ST2 8LG NA Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton Stockton-on-Tees TS19 8BU NA Y Abbey School, Faversham Swale ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Chippenham Wiltshire SN15 3XB N N Abbeyfield School, Northampton Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School South Gloucestershire BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent East Staffordshire DE15 0JL N Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool Liverpool L25 6EE NA Y Abbotsfield School Hillingdon UB10 0EX Y N Abbs Cross School and Arts College Havering RM12 4YQ N -

The Thornburian

THE THORNBURIAN THORNBURY GRAMMAR SCHOOL MAGAZINE JULY-1957 Editor: MARY WILSON No. 23 SCHOOL OFFICERS, 1956—57 School Captains: Mary Wilson (C) J. P. Dickinson (S) School Vice-Captains: Marilyn Avent (C) A. C. Slade (C) School Prefects: Anne Codling (H) R. F. Jackson (C) Gillian White (H) D. J. Morris (S) Kathleen Stephens (C) R. J. Davies (S) Elizabeth Cannock (C) A. C. B. Nicholls (H) Joan Wright (S) G. H. Organ (H) Betty Knapp (H) M. J. Challenger (H) Mary McIntyre (C) C. Tanner (H) Jennifer Morse .(C) M. G. Wright (5) Sheila Fairman (C) R. J. Wells (C) Patricia Parfitt (H) P. H. Hawkins (C) Jean Mood (S) J.H. McTavish (C) Elizabeth lames (S) B. J. Keedwell (H) Margaret Bracey (S) D. H. Price (H) Diana Watkins (H) W. J. Pullin (C) Daphne Jefferies (C) M. G. Hanks (5) Mary Newman (S) M. C. Gregory (C) J. L. Caswell (S) B. J. Nott (H) A. J. Phillips (C) R. G. Collins (H) House Captains: CLARE: Marilyn Avent and A. C. Slade. HOWARD: Gillian White and B. J. Keedwell. STAFFORD: Joan Wright and D. J. Morris. Games Captains: HOCKEY: Mary McIntyre. ASSOCIATION FOOTBALL: R. F. Jackson. RUGBY FOOTBALL: R. F. Jackson. TENNIS: Betty Knapp. CRICKET: P. H. Hawkins. ATHLETICS: Mary McIntyre, A. C. Slade. ROUNDERS: Ruth White, Celia March, Mandy Durnford. SWIMMING: Joan Wright, C. Tanner. NETBALL: 1st VII—Mary Newman; 2nd VII—Celia March; Under 13 VII—Delia Clark. Games Secretaries: Elizabeth Jones, A. I. Phillips. Magazine Editorial Stall: EDITOR: Mary Wilson. SUB-EDITORS: A. J. -

Institution Code Institution Title a and a Co, Nepal

Institution code Institution title 49957 A and A Co, Nepal 37428 A C E R, Manchester 48313 A C Wales Athens, Greece 12126 A M R T C ‐ Vi Form, London Se5 75186 A P V Baker, Peterborough 16538 A School Without Walls, Kensington 75106 A T S Community Employment, Kent 68404 A2z Management Ltd, Salford 48524 Aalborg University 45313 Aalen University of Applied Science 48604 Aalesund College, Norway 15144 Abacus College, Oxford 16106 Abacus Tutors, Brent 89618 Abbey C B S, Eire 14099 Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar Sc 16664 Abbey College, Cambridge 11214 Abbey College, Cambridgeshire 16307 Abbey College, Manchester 11733 Abbey College, Westminster 15779 Abbey College, Worcestershire 89420 Abbey Community College, Eire 89146 Abbey Community College, Ferrybank 89213 Abbey Community College, Rep 10291 Abbey Gate College, Cheshire 13487 Abbey Grange C of E High School Hum 13324 Abbey High School, Worcestershire 16288 Abbey School, Kent 10062 Abbey School, Reading 16425 Abbey Tutorial College, Birmingham 89357 Abbey Vocational School, Eire 12017 Abbey Wood School, Greenwich 13586 Abbeydale Grange School 16540 Abbeyfield School, Chippenham 26348 Abbeylands School, Surrey 12674 Abbot Beyne School, Burton 12694 Abbots Bromley School For Girls, St 25961 Abbot's Hill School, Hertfordshire 12243 Abbotsfield & Swakeleys Sixth Form, 12280 Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge 12732 Abbotsholme School, Staffordshire 10690 Abbs Cross School, Essex 89864 Abc Tuition Centre, Eire 37183 Abercynon Community Educ Centre, Wa 11716 Aberdare Boys School, Rhondda Cynon 10756 Aberdare College of Fe, Rhondda Cyn 10757 Aberdare Girls Comp School, Rhondda 79089 Aberdare Opportunity Shop, Wales 13655 Aberdeen College, Aberdeen 13656 Aberdeen Grammar School, Aberdeen Institution code Institution title 16291 Aberdeen Technical College, Aberdee 79931 Aberdeen Training Centre, Scotland 36576 Abergavenny Careers 26444 Abersychan Comprehensive School, To 26447 Abertillery Comprehensive School, B 95244 Aberystwyth Coll of F. -

1955 This Year Speech Day Was Held on May 26Th, but Preoccupation with the Fate of the Various Political Parties Had No Ill Effects on Any of Those Present

SCHOOL OFFICERS, 1954-55 School Captains: Wendy Slade (C) and I. T. Jackson (H) School I’ice-Captains: Judith Robson (H) and C. H. Shearing (H) School Prefects: Josephine Hurcombe(H) L. J. Griffiths (H) Jean Baghurst (H) A. J. Pritchard (S) Monica Wyatt (C) C, T. Cooper (C) Sylvia Palmer (C) J R. Drewett (H) Pamela Peacock (S) G. Williams (H) Heather Hanks (H) D. C. Exell (H) Ninette Blaker (C) J W. Narbett (H) Jennifer Wooster (H) C. L. Davies (S) Mary Sim (S) Mary Wilson (C) L. Watkins (S) Anne Weekes (S) R. F. Jackson (C) Janet Northover (H) P. Williams (S) Fay Dent (S) J. P. Dickinson (S) Shirley Kingscott (H) R. P. B, Browne (H) House Captains: HOWARD: Judith Robson and C. H. Shearing. STAFFORD: Pamela Peacock and A. J, Pritchard. CLARE: Wendy Slade and C. T. Cooper. Games Captains: HOCKEY: Josephine Hurcombe. NETBALL: Shirley Kingscott. ASSOCIATION FOOTBALL: J. W. Narbett. RUGBY FOOTBALL : L. J. Griffiths. TENNIS : Helen Hardcastle. CRICKET: A. J. Pritchard. ATHLETICS: A. Slade. SWIMMING:Sylvia Palmer and B. J. Rogers, Games Secretaries: Janet Northover and P. Williams. Magazine Editorial Staff: EDITOR: I. T. Jackson. SUB-EDITOR: C. T. Cooper. EDITORIAL This year Speech Day coincided with a General Election, an election that signified the retirement of England’s greatest living statesman—Sit Winston Churchill. The fact that we were able to have our annual prizegiving on an election day is one indication, perhaps, that the British electorate, while remaining responsible, have attained a maturity of outlook, with some preference for reasoned choice over blind enthusiasm. -

The Thornburian July, 1951

THE THORNBURIAN THE THORNBURY GRAMMAR SCHOOL MAGAZINE JULY, 1951 Editor: P. M. HARVEY No. 17 SCHOOL OFFICERS, 1950-51 School Captains: Mary Clutterbuck (H) and M. D. Lewis (S). School Vice-Captains: Joan Timbrell (C) and R. M. Teague (C). School Prefects: Kathleen Withers (C) R. Rosser (S) Pauline Robson (S) G. A. Dicker (H) Patsy Harvey (S) D. R. Cooper (5) Mary Hulbert (H) R. D. Biggin (H) Pat Brown (C) D. J. Malpass (C) Frances Riddiford (S) M. H. Dunn (C) Ann Phillips (S) J. S. Cantrill (S) Barbara Hedges (C) E. J. Locke (C) Pat Arnold (H) D. J. Hamilton (H) Dorothy Rudledge (5) D. G. Hawkins (H) Mary Nicholls (C) 1. P. Blenkinsopp (C) Maureen Weaver (H) House Captains: CLARE: Joan Timbrell and R. M. Teague. STAFFORD: Patsy Harvey and M. D. Lewis. HOWARD: Mary Clutterbuck and G. A. Dicker. Games Captains: HOCKEY: Ann Phillips. ASSOCIATION FOOTBALL: D. J. Hamilton. RUGBY FOOTBALL: M. D. Lewis. TENNIS: Joan Timbrell. CRICKET:D. G. Hawkins. Games Secretaries: Pat Timbrell, D. J. Malpass. Magazine Editorial Staff: EDITOR: Patsy Harvey. SUB-EDITORS: Mary Nicholls, D. R. Cooper. SECRETARY: Wendy Mogg. THE THORNBURIAN EDITORIAL Discord almost always originates from misunderstanding of the other’s point of view, and this explanation is just as applicable to nations as to individuals, whose characteristics and environment usually differ less wide ly. We can best increase the fellowship of nations by visiting other countries and living among their peoples for a time, and this is what many English, and particularly the younger generation, are now doing. -

The Thornburian July, 1952

THE THORNBURIAN THE THORNBURY GRAMMAR SCHOOL MAGAZINE JULY, 1952 Editor: J. M. NICHOLLS No. 18 SCHOOL OFFICERS, 1951-52 School Captains: Pauline Robson (S) (Winter Term). Patsy Harvey (S) (Spring and Summer Terms). D. J. Malpass (C). School Vice-Captains: Patsy Harvey (S), Barbara Hedges (C)~ and M. H. Dunn (C). School Prefects: Patricia Arnold (H) E. J. Locke (C) Mary Nicholls (C). J. P. Blenkinsopp (C) Wendy Mogg (S) C. D. Woodward (S) Molly Willis (C) W. J. Rudledge (H) Pat Timbrell (H) B. D. Thompson (S) Judith Watkins (S) A. C. Darby (C) Margaret Caswell (S) C. J. Radford (S) Muriel James (C) G. D. Watts (H) Ann Buckley (C) G. G. Hannaford (H) Valerie Harding (C) R. A. Sharpe (C) Merle Nicholas (H) J. E. Smith (H) House Captains: CLARE: Barbara Hedges and M. H. Dunn. STAFFORD: Patsy Harvey and C. D Woodward. HOWARD: Patricia Arnold and W. J. Rudledge. Games Captains: HOCKEY: Pat Timbrell. ASSOCIATION FOOTBALL: W. I. Rudledge. RUGBY FOOTBALL: C. D. Woodward. TENNIS: Wendy Mogg. CRICKET:D. J. Malpass. Games Secretaries: Pat Timbrell. D. J. Malpass. Magazine Editorial Staff: EDITOR: Mary Nicholls. SUB-EDITORS:Wendy Mogg and Patsy Harvey. SECRETARIES: Patricia Arnold and E. .J. Locke. THE THORNBURIAN EDITORIAL Recently we had the opportunity of studying the first copy of “The Thornburian,” published in December, 1934, nearly eighteen years ago. To-day, we may be allowed to boast in the fulfilment of a wish expressed in our first edition that the Magazine would “have a long and useful life.” When we look back on the School of 1934, we realise how different were the conditions from those in which we work to-day.