Genetic Diversity and Structure in the Endangered Allen Cays Rock Iguana, Cyclura Cychlura Inornata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biology and Conservation of the Juan Fernandez Archipelago Seabird Community

Biology and Conservation of the Juan Fernández Archipelago Seabird Community Peter Hodum and Michelle Wainstein Dates: 29 December 2001 – 29 March 2002 Participants: Dr. Peter Hodum California State University at Long Beach Long Beach, CA USA Dr. Michelle Wainstein University of Washington Seattle, WA USA Erin Hagen University of Washington Seattle, WA USA Additional contributors: 29 December 2001 – 19 January 2002 Brad Keitt Island Conservation Santa Cruz, CA USA Josh Donlan Island Conservation Santa Cruz, CA USA Karl Campbell Charles Darwin Foundation Galapagos Islands Ecuador 14 January 2002 – 24 March 2002 Ronnie Reyes (student of Dr. Roberto Schlatter) Universidad Austral de Chile Valdivia Chile TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Objectives 3 Research on the pink-footed shearwater 3 Breeding population estimates 4 Reproductive biology and behavior 6 Foraging ecology 7 Competition and predation 8 The storm 9 Research on the Juan Fernández and Stejneger’s petrels 10 Population biology 10 Breeding biology and behavior 11 Foraging ecology 14 Predation 15 The storm 15 Research on the Kermadec petrel 16 Community Involvement 17 Public lectures 17 Seabird drawing contest 17 Radio show 18 Material for CONAF Information Center 18 Local pink-footed shearwater reserve 18 Conservation concerns 19 Streetlights 19 Eradication and restoration 19 Other fauna 20 Acknowledgements 20 Figure 1. Satellite tracks for pink-footed shearwaters 22 Appendices (for English translations please contact P. Hodum or M. Wainstein) A. Proposal for Kermadec petrel research 23 B. Natural history materials left with Information Center 24 C. Proposal for a local shearwater reserve 26 D. Contact information 32 2 INTRODUCTION Six species of seabirds breed on the Juan Fernández Archipelago: the pink-footed shearwater (Puffinus creatopus), Juan Fernández petrel (Pterodroma externa), Stejneger’s petrel (Pterodroma longirostris), Kermadec petrel (Pterodroma neglecta), white-bellied storm petrel (Fregetta grallaria), and Defilippe’s petrel (Pterodroma defilippiana). -

San Nicolas Island Restoration Project, California

San Nicolas Island Restoration Project, California OUR MISSION To protect the Critically Endangered San Nicolas Island Fox, San Nicolas Island Night Lizard, and large colonies of Brandt’s Cormorants from the threat of extinction by removing feral cats. OUR VISION Native animal and plant species on San Nicolas Island reclaim their island home and are thriving. THE PROBLEM For years, introduced feral cats competed with foxes for resources and directly preyed on seabirds and lizards. THE SOLUTION WHY IS SAN NICOLAS In 2010, the U.S. Navy, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Island Conservation, Institute IMPORTANT? for Wildlife Studies, The Humane Society of the United States, and the Montrose Settlement Restoration Program completed the removal and relocation of feral cats to • HOME TO THE ENDEMIC, the permanent, fully enclosed Fund For Animals Wildlife Center in Ramona, California. CRITICALLY ENDANGERED SAN NICOLAS ISLAND THE RESULTS FOX AND FEDERALLY ENDANGERED ISLAND NIGHT Native populations of Critically Endangered San Nicolas Island Foxes (as listed by the LIZARD International Union for the Conservation of Nature) and Brandt’s Cormorants are no • ESSENTIAL NESTING longer at risk of competition and direct predation, and no sign of feral cats has been HABITAT FOR LARGE detected since June 2010. POPULATIONS OF SEABIRD San Nicolas Island This 14,569-acre island, located SPECIES 61 miles due west of Los Angeles, is the most remote of the eight islands in the Channel Island • HOSTS EXPANSIVE Archipelago. The island is owned and managed by ROOKERIES OF SEA LIONS the U.S. Navy. The island is the setting for Scott AND ELEPHANT SEALS O’Dell’s prize-winning 1960 novel, Island of the Blue Dolphins. -

What Is the Importance of Islands to Environmental Conservation?

Environmental Conservation (2017) 44 (4): 311–322 C Foundation for Environmental Conservation 2017 doi:10.1017/S0376892917000479 What is the importance of islands to environmental THEMATIC SECTION Humans and Island conservation? Environments CHRISTOPH KUEFFER∗ 1 AND KEALOHANUIOPUNA KINNEY2 1Institute of Integrative Biology, ETH Zurich, Universitätsstrasse 16, CH-8092 Zurich, Switzerland and 2Institute of Pacifc Islands Forestry, US Forest Service, 60 Nowelo St. Hilo, HI, USA Date submitted: 15 May 2017; Date accepted: 8 August 2017 SUMMARY islands of the world’s oceans, we cover both islands close to continents and others isolated far out in the oceans, and the This article discusses four features of islands that make full range from small to very large islands. Small and isolated them places of special importance to environmental islands represent unique cultural and biological values and the conservation. First, investment in island conservation environmental challenges of insularity in its most pronounced is both urgent and cost-effective. Islands are form. However, as we will demonstrate, all islands and island threatened hotspots of diversity that concentrate people share enough come concerns to consider them together unique cultural, biological and geophysical values, (Baldacchino 2007; Royle 2008; Gillespie & Clague 2009; and they form the basis of the livelihoods of Baldacchino & Niles 2011; Royle 2014). millions of islanders. Second, islands are paradigmatic Islands are hotspots of cultural, biological and geophysical places of human–environment relationships. Island diversity, and as such they form the basis of the livelihoods livelihoods have a long tradition of existing within of millions of islanders (Menard 1986; Nunn 1994; Royle spatial, ecological and ultimately social boundaries 2008; Gillespie & Clague 2009; Royle 2014; Kueffer et al. -

Island Views Volume 3, 2005 — 2006

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper of Channel Islands National Park Island Views Volume 3, 2005 — 2006 Tim Hauf, www.timhaufphotography.com Foxes Returned to the Wild Full Circle In OctobeR anD nOvembeR 2004, The and November 2004, an additional 13 island Chumash Cross Channel in Tomol to Santa Cruz Island National Park Service (NPS) released 23 foxes on Santa Rosa and 10 on San Miguel By Roberta R. Cordero endangered island foxes to the wild from were released to the wild. The foxes will be Member and co-founder of the Chumash Maritime Association their captive rearing facilities on Santa Rosa returned to captivity if three of the 10 on The COastal portion OF OuR InDIg- and San Miguel Islands. Channel Islands San Miguel or five of the 13 foxes on Santa enous homeland stretches from Morro National Park Superintendent Russell Gal- Rosa are killed or injured by golden eagles. Bay in the north to Malibu Point in the ipeau said, “Our primary goal is to restore Releases from captivity on Santa Cruz south, and encompasses the northern natural populations of island fox. Releasing Island will not occur this year since these Channel Islands of Tuqan, Wi’ma, Limuw, foxes to the wild will increase their long- foxes are thought to be at greater risk be- and ‘Anyapakh (San Miguel, Santa Rosa, term chances for survival.” cause they are in close proximity to golden Santa Cruz, and Anacapa). This great, For the past five years the NPS has been eagle territories. -

Our Sea of Islands Our Livelihoods Our Oceania

Status and potential of locally-managed marine areas in the South Pacific: meeting natureOur conservation Sea of and Islands sustainable livelihood targets throughOur wide-spread Livelihoods implementation of LMMAs Our Oceania Framework for a Pacific Oceanscape: a catalyst for implementation of ocean policy Cristelle Pratt and Hugh Govan November 2010 This document was compiled by Cristelle Pratt and Hugh Govan. Part Two of the document was also reviewed by Andrew Smith, Annie Wheeler, Anthony Talouli, Bernard O’Callaghan, Carole Martinez, Caroline Vieux, Catherine Siota, Colleen Corrigan, Coral Pasisi, David Sheppard, Etika Rupeni, Greg Sherley, Jackie Thomas, Jeff Kinch, Kosi Latu, Lindsay Chapman, Maxine Anjiga, Modi Pontio, Olivier Tyack, Padma Lal, Pam Seeto, Paul Anderson, Paul Lokani, Randy Thaman, Samasoni Sauni, Sandeep Singh, Scott Radway, Sue Taei, Tagaloa Cooper, and Taholo Kami at the 2nd Marine Sector Working Group Meeting held in Apia, Samoa, 5–7 April 2010. Photography © Stuart Chape TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE – Toward a Framework for a Pacific Oceanscape: A Policy Analysis 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Context and scope for a Pacific Oceanscape Framework 9 3.0 Instruments – our ocean policy environment 11 3.1 Pacific Plan and Pacific Forum Leaders communiqués 15 3.2 The Pacific Islands Regional Oceans Policy (PIROP) 18 3.3 Synergies with PIROP 18 3.3.1 Relevant international and regional instruments and arrangements 18 3.3.2 Relevant national and non-governmental initiatives 20 4.0 Institutional Framework for Pacific Islands -

Little Islands, Big Strides

Subsistence and commercial fishing, expanding tourism and coastal development are among the stressors facing ecosystems in Micronesia. A miracle in a LITTLE ISLANDS, conference room Kolonia, Federated States of Micronesia — Conservationist BIG STRIDES Bernd Cordes experienced plenty of physical splendor during a ten-day Inspired individuals and Western donors trip to Micronesia in 2017, his first visit to the region in six years. Irides- built a modern conservation movement in cent fish darted out from tropical corals. Wondrous green islands rose Micronesia. But the future of reefs there is from the light blue sea. Manta rays as tenuous as ever. zoomed through the waves off a beach covered in wild coconut trees. But it was inside an overheated By Eli Kintisch conference room on the island of Pohnpei that Cordes witnessed Palau/FSM Profile 1 perhaps the most impressive sight on his trip. There, on the nondescript premises of the Micronesia Con- servation Trust, or MCT, staff from a dozen or so environmental groups operating across the region attended a three-day session led by officials at MCT, which provides $1.5 million each year to these and other groups. Cordes wasn’t interested, per se, in the contents of the discussions. After all, these were the kind of optimistic PowerPoint talks, mixed with sessions on financial reporting and compliance, that you might find at a meeting between a donor and its grantees anywhere in the world. Yet in that banality, for Cordes, lay the triumph. MCT funds projects Most households in the Federated States of Micronesia rely on subsistence fishing. -

New Hope for Threatened Iguanas of Cabritos Island

New Hope for Threatened Iguanas of Cabritos Island islandconservation.org /new-hope-threatened-iguanas-cabritos-island/ Island Conservation 11/1/2017 Some Good News for Caribbean Species: Threatened Iguanas Can Now Safely Breed on Cabritos Island For release on Nov. 1 Contact: Sally Esposito, Island Conservation, [email protected], (706) 969-2783 The Critically Endangered Ricord’s Iguana and the Vulnerable Rhinoceros Iguana can once again thrive on Cabritos Island, Dominican Republic after the successful removal of a suite of invasive species. After extensive monitoring by a team of international organizations, the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources of the Dominican Republic, SOH Conservation, and Island Conservation confirmed Cabritos Island’s native iguanas are poised for recovery following the successful removal of introduced, damaging (invasive) donkeys, feral cats, and cows from the island. The effort began in 2013 with the training of a local field team in island restoration techniques. Since then, the Critically Endangered[1] Ricord’s and Vulnerable Rhinoceros’ Iguanas have gone through multiple breeding seasons where the invasive species populations were greatly reduced or absent, and evidence of recovery is everywhere. Wesley Jolley, Cabritos Project Manager at Island Conservation said: Today, the island is filled with juvenile iguanas scurrying about, a sight rarely seen when invasive species were present. Native vegetation is also thriving. Now, Cabritos Island is the only place on Earth where the Critically Endangered Ricord’s Iguana can roam free from the threat of feral cats, donkeys and cows. These threatened iguanas survive as four populations, with three in the Southwest of the Dominican Republic and one in Haiti. -

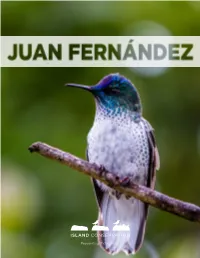

Why Juan Fernández?

THE JUAN FERNÁNDEZ ARCHIPELAGO A RACE AGAINST TIME TO SAFEGUARD ISLAND LIFE Island Conservation’s mission is to prevent extinctions by removing invasive species from islands. Our Juan Fernández Program aims to restore native island ecosystems that promote the sustainable development of the local community. Through the removal of invasive alien species (IAS)1, we will prevent extinctions, build capacity, and improve human livelihoods in the archipelago. WHY JUAN FERNÁNDEZ? ISOLATION ENDEMISM EXTINCTION RESILIENCE The islands grew from volcanic The land that comprises the According to IUCN2 Red List Invasive alien species (IAS) activity six million years ago archipelago is home to over criteria, 89 native plant and are the leading threat to and emerged 700 km off the 900 plant and animal species; six native bird species are a prosperous archipelago. Chilean coast. Native species 64% are endemic, found only threatened with extinction. Removing IAS will restore developed and flourished in here. Many species are highly Nine plant species can no balance to the ecosystem the unique conditions of this vulnerable to invasive species longer be found in native by protecting threatened remote paradise. that have been inadvertently forests. native species and the natural introduced since European resources that island residents discovery. depend on. TURNING CHALLENGES INTO OPPORTUNITIES TAKING ACTION ISLAND CONSERVATION LOCAL CAPACITY Close collaboration with local partners Island Conservation (IC) is ideally Our partners in the archipelago have a and agencies allows us to conduct positioned to add conservation value history of controlling invasive species. research and lay much of the by designing and implementing IAS By complementing their knowledge and groundwork necessary to restore the eradications; our strong ties to the local skills, we are working together towards island ecosystems. -

Gregg Howald CV

CAREER ASPIRATIONS Gregg To implement, catalyze and inspire biodiversity conservation through sustainable partnerships for the benefit of wildlife and people. Howald PROFESSIONAL OVERVIEW > Building conservation programs. Over 20 years of experience protecting threatened species by building multi‐lateral/transboundary partnerships focused on the restoration of island ecosystems in the temperate and tropical Pacific. > Building and sustaining long term public‐private partnerships by bringing industry, government, scientists and NGOs together under national and international policy frameworks to conserve threatened species. > Effectively communicating the science of conservation and environmental issues in support of complex environmental compliance processes (eg. NEPA; FIFRA), controversial public consultation, media and advocacy. > Applying the science of ecotoxicology and environmental risk assessment for toxin based invasive species management projects. > Catalyzing the innovation of new, more effective and safer conservation tools to facilitate larger, more complex, or currently unattainable restoration actions. > Mentoring the next generation of conservationists through collaborative working relationships and sharing of expertise internationally. EXPERIENCE 2010‐Present Island Conservation (IC) North America Regional Director > Develop and implement a strategic plan for IC in North America. > Build and maintain partnerships with a diverse group of First Nations, government, funders, NGO, corporate and landowner stakeholders to implement -

From Its Inception, the Garden Has Had Research Connections with the California Channel Islands

THE CHANNEL ISLANDS: SPECIAL PLACES IN THE GARDEN’S HISTORY By Steve Junak, SBBG Research Department The Northern Channel Islands are a familiar sight for the residents of the Santa Barbara area. Situated just off our coast, the islands of San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, and Anacapa are often clearly visible from the mainland. For more than a century, the plants of the Channel Islands have captured the interest and imagination of botanists and horticulturists from around the world. The Garden has played an important role in making the public aware of the beauty, utility, horticultural requirements, and scientific characteristics of island plants, many of which are widely used and admired by gardeners today. Island Studies at the Garden from the 1920s until the 1940s When the Garden was officially founded in March 1926, it was part of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. As we can tie our very beginnings to the Museum, we can tie our island legacy to Ralph Hoffmann. Hoffmann, who was the Museum’s director from 1925 to 1932, made dozens of plant collecting trips to the Channel Islands. He was often accompanied by other botanists and undoubtedly influenced the Garden’s new staff. A meticulous collector who was unafraid of steep cliffs, Hoffmann made many exciting discoveries on the islands. His herbarium specimens (many of which are now in the Garden’s herbarium), unpublished flora of the Northern Channel Islands, and published papers on island plants have contributed significantly to our current knowledge of the island flora. Among the plants named in his honor are Hoffmann’s rock cress (Arabis hoffmannii), known only from Santa Rosa and Santa Cruz islands, and Hoffmann’s snake root (Sanicula hoffmannii), found on the islands and in coastal areas on the mainland. -

Atolls of the Tropical Pacific Ocean: Wetlands Under Threat

Atolls of the Tropical Pacific Ocean: Wetlands Under Threat R. R. Thaman Contents Introduction ....................................................................................... 2 Pacific Atolls Described .......................................................................... 3 Distribution ....................................................................................... 5 Atoll Biodiversity ................................................................................. 6 Ecosystem and Habitat Diversity ................................................................. 7 Species and Taxonomic Diversity ................................................................ 10 Genetic Diversity ................................................................................. 13 Ecosystem Goods and Services .................................................................. 13 Threats and Future Challenges ................................................................... 13 Conservation of Atoll Ecosystems ............................................................... 19 Conclusion ........................................................................................ 22 References ........................................................................................ 23 Abstract Atolls are small, geographically isolated, resource-poor islands scattered over vast expanses of ocean. There is little potential for modern economic or com- mercial development, and most Pacific Island atoll countries and communities depend almost entirely -

Choros Island, Chile

Choros Island, Chile OUR MISSION To protect the globally threatened seabird and plant species that depend on and Choros Island. OUR VISION The island’s native species are thriving and free from the threat of invasive species. THE PROBLEM Invasive European rabbits are destroying nesting habitat for penguins and petrels and devouring the island’s vegetation. WHY IS CHOROS ISLAND IMPORTANT? THE SOLUTION In support of work led by CONAF (the Chilean government agency responsible for • 1,700 to 2,000 Humboldt protected areas and forest management), Island Conservation, local community leaders, Penguin pairs breed on and scientists are working together to restore populations of native species on Choros Choros Island Island by removing invasive rabbits. • Choros is one of only four WHY MEASURE OUR IMPACT? islands in Chile where the By comparing the population size of animals and plants before and after removal of invasive rabbits, we can measure the impact that our actions have in restoring key Peruvian Diving-petrel nests, habitat and threatened species, such as the Endangered Peruvian Diving-petrel and representing at least 10% of Vulnerable Humboldt Penguin. Monitoring our impact ensures that island restoration its global population efforts are successful, imperiled species are protected, and ecotourism continues to • Choros is a Chilean develop. Choros island is one of the three islands that protected area and, once make up the Humboldt Penguin National restored, will provide ideal Reserve, situated 600 km (372.8 miles) north of Santiago, Chile. The reserve is managed breeding sites for these bird and protected by CONAF. Choros Island species covers 301 ha.