MICRONESIANS in ISLAND CONSERVATION Lessons from a Conservation Leaders’ Learning Network: 2000 - 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

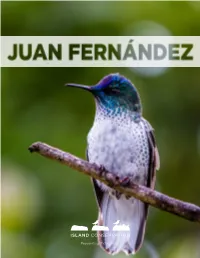

Biology and Conservation of the Juan Fernandez Archipelago Seabird Community

Biology and Conservation of the Juan Fernández Archipelago Seabird Community Peter Hodum and Michelle Wainstein Dates: 29 December 2001 – 29 March 2002 Participants: Dr. Peter Hodum California State University at Long Beach Long Beach, CA USA Dr. Michelle Wainstein University of Washington Seattle, WA USA Erin Hagen University of Washington Seattle, WA USA Additional contributors: 29 December 2001 – 19 January 2002 Brad Keitt Island Conservation Santa Cruz, CA USA Josh Donlan Island Conservation Santa Cruz, CA USA Karl Campbell Charles Darwin Foundation Galapagos Islands Ecuador 14 January 2002 – 24 March 2002 Ronnie Reyes (student of Dr. Roberto Schlatter) Universidad Austral de Chile Valdivia Chile TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Objectives 3 Research on the pink-footed shearwater 3 Breeding population estimates 4 Reproductive biology and behavior 6 Foraging ecology 7 Competition and predation 8 The storm 9 Research on the Juan Fernández and Stejneger’s petrels 10 Population biology 10 Breeding biology and behavior 11 Foraging ecology 14 Predation 15 The storm 15 Research on the Kermadec petrel 16 Community Involvement 17 Public lectures 17 Seabird drawing contest 17 Radio show 18 Material for CONAF Information Center 18 Local pink-footed shearwater reserve 18 Conservation concerns 19 Streetlights 19 Eradication and restoration 19 Other fauna 20 Acknowledgements 20 Figure 1. Satellite tracks for pink-footed shearwaters 22 Appendices (for English translations please contact P. Hodum or M. Wainstein) A. Proposal for Kermadec petrel research 23 B. Natural history materials left with Information Center 24 C. Proposal for a local shearwater reserve 26 D. Contact information 32 2 INTRODUCTION Six species of seabirds breed on the Juan Fernández Archipelago: the pink-footed shearwater (Puffinus creatopus), Juan Fernández petrel (Pterodroma externa), Stejneger’s petrel (Pterodroma longirostris), Kermadec petrel (Pterodroma neglecta), white-bellied storm petrel (Fregetta grallaria), and Defilippe’s petrel (Pterodroma defilippiana). -

San Nicolas Island Restoration Project, California

San Nicolas Island Restoration Project, California OUR MISSION To protect the Critically Endangered San Nicolas Island Fox, San Nicolas Island Night Lizard, and large colonies of Brandt’s Cormorants from the threat of extinction by removing feral cats. OUR VISION Native animal and plant species on San Nicolas Island reclaim their island home and are thriving. THE PROBLEM For years, introduced feral cats competed with foxes for resources and directly preyed on seabirds and lizards. THE SOLUTION WHY IS SAN NICOLAS In 2010, the U.S. Navy, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Island Conservation, Institute IMPORTANT? for Wildlife Studies, The Humane Society of the United States, and the Montrose Settlement Restoration Program completed the removal and relocation of feral cats to • HOME TO THE ENDEMIC, the permanent, fully enclosed Fund For Animals Wildlife Center in Ramona, California. CRITICALLY ENDANGERED SAN NICOLAS ISLAND THE RESULTS FOX AND FEDERALLY ENDANGERED ISLAND NIGHT Native populations of Critically Endangered San Nicolas Island Foxes (as listed by the LIZARD International Union for the Conservation of Nature) and Brandt’s Cormorants are no • ESSENTIAL NESTING longer at risk of competition and direct predation, and no sign of feral cats has been HABITAT FOR LARGE detected since June 2010. POPULATIONS OF SEABIRD San Nicolas Island This 14,569-acre island, located SPECIES 61 miles due west of Los Angeles, is the most remote of the eight islands in the Channel Island • HOSTS EXPANSIVE Archipelago. The island is owned and managed by ROOKERIES OF SEA LIONS the U.S. Navy. The island is the setting for Scott AND ELEPHANT SEALS O’Dell’s prize-winning 1960 novel, Island of the Blue Dolphins. -

What Is the Importance of Islands to Environmental Conservation?

Environmental Conservation (2017) 44 (4): 311–322 C Foundation for Environmental Conservation 2017 doi:10.1017/S0376892917000479 What is the importance of islands to environmental THEMATIC SECTION Humans and Island conservation? Environments CHRISTOPH KUEFFER∗ 1 AND KEALOHANUIOPUNA KINNEY2 1Institute of Integrative Biology, ETH Zurich, Universitätsstrasse 16, CH-8092 Zurich, Switzerland and 2Institute of Pacifc Islands Forestry, US Forest Service, 60 Nowelo St. Hilo, HI, USA Date submitted: 15 May 2017; Date accepted: 8 August 2017 SUMMARY islands of the world’s oceans, we cover both islands close to continents and others isolated far out in the oceans, and the This article discusses four features of islands that make full range from small to very large islands. Small and isolated them places of special importance to environmental islands represent unique cultural and biological values and the conservation. First, investment in island conservation environmental challenges of insularity in its most pronounced is both urgent and cost-effective. Islands are form. However, as we will demonstrate, all islands and island threatened hotspots of diversity that concentrate people share enough come concerns to consider them together unique cultural, biological and geophysical values, (Baldacchino 2007; Royle 2008; Gillespie & Clague 2009; and they form the basis of the livelihoods of Baldacchino & Niles 2011; Royle 2014). millions of islanders. Second, islands are paradigmatic Islands are hotspots of cultural, biological and geophysical places of human–environment relationships. Island diversity, and as such they form the basis of the livelihoods livelihoods have a long tradition of existing within of millions of islanders (Menard 1986; Nunn 1994; Royle spatial, ecological and ultimately social boundaries 2008; Gillespie & Clague 2009; Royle 2014; Kueffer et al. -

Island Views Volume 3, 2005 — 2006

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper of Channel Islands National Park Island Views Volume 3, 2005 — 2006 Tim Hauf, www.timhaufphotography.com Foxes Returned to the Wild Full Circle In OctobeR anD nOvembeR 2004, The and November 2004, an additional 13 island Chumash Cross Channel in Tomol to Santa Cruz Island National Park Service (NPS) released 23 foxes on Santa Rosa and 10 on San Miguel By Roberta R. Cordero endangered island foxes to the wild from were released to the wild. The foxes will be Member and co-founder of the Chumash Maritime Association their captive rearing facilities on Santa Rosa returned to captivity if three of the 10 on The COastal portion OF OuR InDIg- and San Miguel Islands. Channel Islands San Miguel or five of the 13 foxes on Santa enous homeland stretches from Morro National Park Superintendent Russell Gal- Rosa are killed or injured by golden eagles. Bay in the north to Malibu Point in the ipeau said, “Our primary goal is to restore Releases from captivity on Santa Cruz south, and encompasses the northern natural populations of island fox. Releasing Island will not occur this year since these Channel Islands of Tuqan, Wi’ma, Limuw, foxes to the wild will increase their long- foxes are thought to be at greater risk be- and ‘Anyapakh (San Miguel, Santa Rosa, term chances for survival.” cause they are in close proximity to golden Santa Cruz, and Anacapa). This great, For the past five years the NPS has been eagle territories. -

Our Sea of Islands Our Livelihoods Our Oceania

Status and potential of locally-managed marine areas in the South Pacific: meeting natureOur conservation Sea of and Islands sustainable livelihood targets throughOur wide-spread Livelihoods implementation of LMMAs Our Oceania Framework for a Pacific Oceanscape: a catalyst for implementation of ocean policy Cristelle Pratt and Hugh Govan November 2010 This document was compiled by Cristelle Pratt and Hugh Govan. Part Two of the document was also reviewed by Andrew Smith, Annie Wheeler, Anthony Talouli, Bernard O’Callaghan, Carole Martinez, Caroline Vieux, Catherine Siota, Colleen Corrigan, Coral Pasisi, David Sheppard, Etika Rupeni, Greg Sherley, Jackie Thomas, Jeff Kinch, Kosi Latu, Lindsay Chapman, Maxine Anjiga, Modi Pontio, Olivier Tyack, Padma Lal, Pam Seeto, Paul Anderson, Paul Lokani, Randy Thaman, Samasoni Sauni, Sandeep Singh, Scott Radway, Sue Taei, Tagaloa Cooper, and Taholo Kami at the 2nd Marine Sector Working Group Meeting held in Apia, Samoa, 5–7 April 2010. Photography © Stuart Chape TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE – Toward a Framework for a Pacific Oceanscape: A Policy Analysis 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Context and scope for a Pacific Oceanscape Framework 9 3.0 Instruments – our ocean policy environment 11 3.1 Pacific Plan and Pacific Forum Leaders communiqués 15 3.2 The Pacific Islands Regional Oceans Policy (PIROP) 18 3.3 Synergies with PIROP 18 3.3.1 Relevant international and regional instruments and arrangements 18 3.3.2 Relevant national and non-governmental initiatives 20 4.0 Institutional Framework for Pacific Islands -

Little Islands, Big Strides

Subsistence and commercial fishing, expanding tourism and coastal development are among the stressors facing ecosystems in Micronesia. A miracle in a LITTLE ISLANDS, conference room Kolonia, Federated States of Micronesia — Conservationist BIG STRIDES Bernd Cordes experienced plenty of physical splendor during a ten-day Inspired individuals and Western donors trip to Micronesia in 2017, his first visit to the region in six years. Irides- built a modern conservation movement in cent fish darted out from tropical corals. Wondrous green islands rose Micronesia. But the future of reefs there is from the light blue sea. Manta rays as tenuous as ever. zoomed through the waves off a beach covered in wild coconut trees. But it was inside an overheated By Eli Kintisch conference room on the island of Pohnpei that Cordes witnessed Palau/FSM Profile 1 perhaps the most impressive sight on his trip. There, on the nondescript premises of the Micronesia Con- servation Trust, or MCT, staff from a dozen or so environmental groups operating across the region attended a three-day session led by officials at MCT, which provides $1.5 million each year to these and other groups. Cordes wasn’t interested, per se, in the contents of the discussions. After all, these were the kind of optimistic PowerPoint talks, mixed with sessions on financial reporting and compliance, that you might find at a meeting between a donor and its grantees anywhere in the world. Yet in that banality, for Cordes, lay the triumph. MCT funds projects Most households in the Federated States of Micronesia rely on subsistence fishing. -

New Hope for Threatened Iguanas of Cabritos Island

New Hope for Threatened Iguanas of Cabritos Island islandconservation.org /new-hope-threatened-iguanas-cabritos-island/ Island Conservation 11/1/2017 Some Good News for Caribbean Species: Threatened Iguanas Can Now Safely Breed on Cabritos Island For release on Nov. 1 Contact: Sally Esposito, Island Conservation, [email protected], (706) 969-2783 The Critically Endangered Ricord’s Iguana and the Vulnerable Rhinoceros Iguana can once again thrive on Cabritos Island, Dominican Republic after the successful removal of a suite of invasive species. After extensive monitoring by a team of international organizations, the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources of the Dominican Republic, SOH Conservation, and Island Conservation confirmed Cabritos Island’s native iguanas are poised for recovery following the successful removal of introduced, damaging (invasive) donkeys, feral cats, and cows from the island. The effort began in 2013 with the training of a local field team in island restoration techniques. Since then, the Critically Endangered[1] Ricord’s and Vulnerable Rhinoceros’ Iguanas have gone through multiple breeding seasons where the invasive species populations were greatly reduced or absent, and evidence of recovery is everywhere. Wesley Jolley, Cabritos Project Manager at Island Conservation said: Today, the island is filled with juvenile iguanas scurrying about, a sight rarely seen when invasive species were present. Native vegetation is also thriving. Now, Cabritos Island is the only place on Earth where the Critically Endangered Ricord’s Iguana can roam free from the threat of feral cats, donkeys and cows. These threatened iguanas survive as four populations, with three in the Southwest of the Dominican Republic and one in Haiti. -

CBD Fifth National Report

Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity The Federated States of Micronesia 2014 This report was prepared by the Micronesia Conservation Trust in collaboration with the Federated States of Micronesia Resources and Development Department with the generous financial assistance of the Global Environment Facility. Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 3 Part I: Update to the status, trends, threats and implications for human wellbeing Q1: Why is biodiversity important for the Federated States of Micronesia? ...................................... 8 Q2: What major changes have taken place in the status and trends of biodiversity? .................... 15 Q3: What are the main threats to biodiversity? ......................................................................................... 22 Q4: What are the impacts of the changes in biodiversity for ecosystem services and the socio- economic and cultural implications of these impacts? ............................................................................ 27 Part II: Biodiversity strategic action plans, their implementation, and the mainstreaming of biodiversity Q5: What are the country’s biodiversity targets? ..................................................................................... 30 Q6: How have the country’s biodiversity strategic action plans been updated to incorporate these targets? ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Why Juan Fernández?

THE JUAN FERNÁNDEZ ARCHIPELAGO A RACE AGAINST TIME TO SAFEGUARD ISLAND LIFE Island Conservation’s mission is to prevent extinctions by removing invasive species from islands. Our Juan Fernández Program aims to restore native island ecosystems that promote the sustainable development of the local community. Through the removal of invasive alien species (IAS)1, we will prevent extinctions, build capacity, and improve human livelihoods in the archipelago. WHY JUAN FERNÁNDEZ? ISOLATION ENDEMISM EXTINCTION RESILIENCE The islands grew from volcanic The land that comprises the According to IUCN2 Red List Invasive alien species (IAS) activity six million years ago archipelago is home to over criteria, 89 native plant and are the leading threat to and emerged 700 km off the 900 plant and animal species; six native bird species are a prosperous archipelago. Chilean coast. Native species 64% are endemic, found only threatened with extinction. Removing IAS will restore developed and flourished in here. Many species are highly Nine plant species can no balance to the ecosystem the unique conditions of this vulnerable to invasive species longer be found in native by protecting threatened remote paradise. that have been inadvertently forests. native species and the natural introduced since European resources that island residents discovery. depend on. TURNING CHALLENGES INTO OPPORTUNITIES TAKING ACTION ISLAND CONSERVATION LOCAL CAPACITY Close collaboration with local partners Island Conservation (IC) is ideally Our partners in the archipelago have a and agencies allows us to conduct positioned to add conservation value history of controlling invasive species. research and lay much of the by designing and implementing IAS By complementing their knowledge and groundwork necessary to restore the eradications; our strong ties to the local skills, we are working together towards island ecosystems. -

Micronesia Challenge Action Planning Meeting

Micronesia Challenge Action Planning Meeting December 4 – 7, 2006 Republic of Palau Index Acronyms ____________________________________________________________________ 3 Participants __________________________________________________________________ 4 Jurisdictional Status Reports____________________________________________________ 7 Executive Session _____________________________________________________________ 7 Policy & Finance Session _______________________________________________________ 9 Technical Sessions ___________________________________________________________ 11 I. Effective Conservation Breakout Session _______________________________________ 11 II. 30% Near-shore Marine Breakout Session ______________________________________ 12 III. 20% Terrestrial Breakout Session_____________________________________________ 13 IV. Outreach Breakout Session_________________________________________________ 15 Jurisdictional Breakout Sessions _______________________________________________ 16 Recommendations to the Chief Executives ________________________________________ 17 Next Steps __________________________________________________________________ 18 Attachment 1: Republic of Palau (ROP) Status Report ______________________________ 20 Attachment 2: Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) Status Report ___________________ 23 Attachment 3: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) Status Report____ 25 Attachment 4: U.S. Territory of Guam Status Report________________________________ 29 Attachment 5: Republic of the Marshall Islands -

Gregg Howald CV

CAREER ASPIRATIONS Gregg To implement, catalyze and inspire biodiversity conservation through sustainable partnerships for the benefit of wildlife and people. Howald PROFESSIONAL OVERVIEW > Building conservation programs. Over 20 years of experience protecting threatened species by building multi‐lateral/transboundary partnerships focused on the restoration of island ecosystems in the temperate and tropical Pacific. > Building and sustaining long term public‐private partnerships by bringing industry, government, scientists and NGOs together under national and international policy frameworks to conserve threatened species. > Effectively communicating the science of conservation and environmental issues in support of complex environmental compliance processes (eg. NEPA; FIFRA), controversial public consultation, media and advocacy. > Applying the science of ecotoxicology and environmental risk assessment for toxin based invasive species management projects. > Catalyzing the innovation of new, more effective and safer conservation tools to facilitate larger, more complex, or currently unattainable restoration actions. > Mentoring the next generation of conservationists through collaborative working relationships and sharing of expertise internationally. EXPERIENCE 2010‐Present Island Conservation (IC) North America Regional Director > Develop and implement a strategic plan for IC in North America. > Build and maintain partnerships with a diverse group of First Nations, government, funders, NGO, corporate and landowner stakeholders to implement -

Micronesia Challenge "We Are One" Business Plan

We are One Business Plan and Conservation Campaign Micronesia Challenge This page: Natural wonders are found even in the smallest riffles, such as this one in Kosrae. ©KCSO. Cover: The Micronesia Challenge seeks to permanently protect mountain to reef habitats and the species that live within them, such as these Yellow Tail Fusiliers. ©Ethan Daniels/Shutterstock. Our wonders Your generosity A future secured We are One Help protect some of the most pristine, splendid environments on earth. The Micronesia Challenge brings together three nations, two territories, thousands of communities, and hundreds of international partners all working as one to permanently and effectively protect over 14,000 square kilometers of marine and terrestrial habitats. By helping us reach our goal of raising $55 million dollars for an endowment to support a wide range of annual conservation activities, you will help us protect thousands of unique and endemic species, and preserve a way of life for generations to come. Please, give generously to the Micronesia Challenge. We are Micronesia We are One Republic of Palau U.S. Territory of Guam U.S. Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Federated States of Micronesia Republic of the Marshall Islands Micronesia is alike, yet different. Isolated, yet connected. Small, but immense. e are joined as one. For our children, and the world. 500,000 people. 2,000 islands. 12 languages. 5 Micronesian jurisdictions. From the top: Flags of Palau, Guam, CNMI, FSM, and RMI Underwater scenes such as this one highlight the variety of macro- and microfauna present on Micronesian Reefs. ©Isabelle Kuehn/Shutterstock. 30, 20, one Micronesia The Micronesia Challenge is a shared commitment to conserve at least 30% of near-shore marine resources and 20% of terrestrial resources across Micronesia by 2020.