The Mendicant Orders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Complete Course

A Complete Course Forum Theological Midwest Author: Rev.© Peter V. Armenio Publisher:www.theologicalforum.org Rev. James Socias Copyright MIDWEST THEOLOGICAL FORUM Downers Grove, Illinois iii CONTENTS xiv Abbreviations Used for 43 Sidebar: The Sanhedrin the Books of the Bible 44 St. Paul xiv Abbreviations Used for 44 The Conversion of St. Paul Documents of the Magisterium 46 An Interlude—the Conversion of Cornelius and the Commencement of the Mission xv Foreword by Francis Cardinal George, to the Gentiles Archbishop of Chicago 47 St. Paul, “Apostle of the Gentiles” xvi Introduction 48 Sidebar and Maps: The Travels of St. Paul 50 The Council of Jerusalem (A.D. 49– 50) 1 Background to Church History: 51 Missionary Activities of the Apostles The Roman World 54 Sidebar: Magicians and Imposter Apostles 3 Part I: The Hellenistic Worldview 54 Conclusion 4 Map: Alexander’s Empire 55 Study Guide 5 Part II: The Romans 6 Map: The Roman Empire 59 Chapter 2: The Early Christians 8 Roman Expansion and the Rise of the Empire 62 Part I: Beliefs and Practices: The Spiritual 9 Sidebar: Spartacus, Leader of a Slave Revolt Life of the Early Christians 10 The Roman Empire: The Reign of Augustus 63 Baptism 11 Sidebar: All Roads Lead to Rome 65 Agape and the Eucharist 12 Cultural Impact of the Romans 66 Churches 13 Religion in the Roman Republic and 67 Sidebar: The Catacombs Roman Empire 68 Maps: The Early Growth of Christianity 14 Foreign Cults 70 Holy Days 15 Stoicism 70 Sidebar: Christian Symbols 15 Economic and Social Stratification of 71 The Papacy Roman -

Special Report on Religious Life

Catholic News Agency and women who Year-long MAJOR ORDERS TYPES OF RELIGIOUS ORDERS dedicate their lives celebrations AND THEIR CHARISMS to prayer, service The Roman Catholic Church recognizes different types of religious orders: and devotion. Year of Marriage, A religious order or congregation is Many also live as Nov. 2014- distinguished by a charism, or particular • Monastic: Monks or nuns live and work in a monastery; the largest monastic order, part of a commu- Dec. 2015 grace granted by God to the institute’s which dates back to the 6th century, is the Benedictines. nity that follows a founder or the institute itself. Here • Mendicant: Friars or nuns who live from alms and actively participate in apostolic work; specific religious Year of Faith, are just a few religious orders and the Dominicans and Franciscans are two of the most well-known mendicant orders. rule. They can Year of Prayer, congregations with their charisms: • Canons Regular: Priests living in a community and active in a particular parish. include both Oct. 2012- • Clerks Regular: Priests who are also religious men with vows and who actively clergy and laity. Nov. 2013 Order/ participate in apostolic work. Most make public Congregation: Charism: vows of poverty, Year for Priests, obedience and June 2009- Dominicans Preaching and chastity. Priests June 2010 teaching who are religious Benedictines Liturgical are different from Year of St. Paul, prayer and diocesan priests, June 2008- monasticism who do not take June 2009 Missionaries Serving God vows. of Charity among the Religious congregations differ from reli- “poorest of the gious orders mainly in terms of the vows poor” that are taken. -

Mendicant Orders of the Middle Ages

Mendicant Orders of the Middle Ages The Monks and Monasteries of the early Middle Ages played a critical roal in the preservation and promotion of Christian culture. The accomplishments of the monks, especially during the 'Dark Ages', are too numerous to list. They were the both missionaries and custodians of Catholic culture for generations, and the monastic reforms of the tenth century paved the way for the reforms of the secular clergy that followed. By the beginning of the 13th century, however, there was seen a need for a new type of religious community, and thus were born the Mendicant Orders. The word 'Mendicant' means beggar, and this was due to the fact that the Mendicant Friars, in contrast to the Benedictine Monks, lived primarily in towns, rather than on propertied estates. Since they did not own property, they were not beholden to secular rulers and were free to serve the poor, preach the gospel, and uphold Christian ideals without compromise. The Investiture Controversy of the previous century, and the underlying problems of having prelates appointed by and loyal to local princes, was one of the reasons for the formation of mendicant orders. Even though monks took a vow of personal poverty, they were frequently members of wealthy monasteries, which were alway prone to corruption and politics. The mendicant commitment to poverty, therefore, prohibited the holding of income producing property by the orders, as well as individuals. The poverty of the mendicant orders gave them great freedom, in the selection of their leaders, in the their mobility, and in their active pursuits. -

The Mendicant Preachers and the Merchant's Soul

MARK HANSSEN THE MENDICANT PREACHERS AND THE MERCHANT'S SOUL THE CIVILIZATION OF COMMERCE IN THE LATE- MIDDLE AGES AND RENAISSANCE ITALY (1275-1425) Tesis doctoral dirigida por PROF. DR. MIGUEL ALFONSO MARTÍNEZ-ECHEVARRÍA Y ORTEGA PROF. DR. ANTONIO MORENO ALMÁRCEGUI FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS Y EMPRESARIALES PAMPLONA, 2014 Table of contents Prologue .......................................................................................................... 7 PART I: BACKGROUND Chapter 1: Introduction The Merchant in the Wilderness ............................. 27 1. Economic Autarky and Carolingian Political "Augustinianism" ........................ 27 2. The Commercial Revolution ................................................................................ 39 3. Eschatology and Civilization ............................................................................... 54 4. Plan of the Work .................................................................................................. 66 Chapter 2: Theology and Civilization ........................................................... 73 1. Theology and Humanism ..................................................................................... 73 2. Christianity and Classical Culture ...................................................................... 83 3. Justice, Commerce and Political Society............................................................. 95 PART II: SCHOLASTIC PHILOSOPHICAL-THEOLOGY, ETHICS AND POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Introduction................................................................................................ -

UNIFICATION and CONFLICT the Church Politics Of

STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA LXXXVI UNIFICATION AND CONFLICT The Church Politics of Alonso de Montúfar OP, Archbishop of Mexico, 1554-1572. Magnus Lundberg COPYRIGHT © Magnus Lundberg 2002 Lund University Department of Theology and Religious Studies Allhelgona kyrkogata 8, SE-223 62 Lund, Sweden PRINTED IN SWEDEN BY KFS i Lund AB, Lund 2002 ISSN 1404-9503 ISBN 91-85424-69-2 PUBLISHED AND DISTRIBUTED BY Swedish Institute of Missionary Research P.O. Box 1526 SE-751 45 Uppsala, Sweden 2 Alonso de Montúfar OP The Metropolitan Cathedral, Mexico City. Photo: Magnus Lundberg. 3 Alonso de Montúfar OP Santa Cruz la Real, Granada. Photo: Roberto Travesí. (Huerga 1995:81). 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writing of a doctoral dissertation implies many hours of solitary work. This is not least the case if you spend most of your days in the company of a man who died over four hundred years ago, as I have done in the last couple of years. Therefore, I here want to take the opportunity to acknowledge some of the many people who have made my work less lonely and who have helped me in various ways. My first sincere words of acknowledgement are due to my supervisor Dr. Aasulv Lande, Professor of Missiology with Ecumenical Theology at Lund University, who has been an unfailing source of encouragement during my years of undergraduate and graduate studies. In particular I want to thank him for believing in my dissertation project even in the dark periods when I did not do so myself. Likewise, I am especially indebted to Professor emeritus Magnus Mörner, who kindly accepted to become my assistant supervisor. -

What's New About the New Evangelization?

SILVER LAKE COLLEGE OF THE HOLY FAMILY What’s New About the New Evangelization? Learning from our heritage Sister Marie Kolbe Zamora, S.T.L. Contents What’s New About the New Evangelization? Learning from our heritage. .................................................. 3 Introduction: ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Purpose of this Presentation ........................................................................................................................ 3 Outline of this Presentation .......................................................................................................................... 4 What IS the New Evangelization? ................................................................................................................. 4 Overcoming Obstacles .............................................................................................................................. 5 Defining Evangelization ............................................................................................................................. 5 First Wave of Evangelization - Evangelizing Greco-Roman World ................................................................ 6 Era Context / Recipients............................................................................................................................ 6 First Wave of Evangelization Details: ....................................................................................................... -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

The Architecture of the Mendicant Orders in the Middle Ages: an Overview of Recent Literature

The Architecture of the Mendicant Orders in the Middle Ages: An Overview of Recent Literature Caroline Bruzelius European cities of any size had one or more mendicant convents. These institutions re- shaped the topographical, social, and economic realities of urban life in the late Middle Ages; they also often de-stabilized traditional parochial organization and created new poles of influence and activity within cities. Mendicants expanded and “anchored” new suburbs, but they sometimes also settled in the heart of a city, destroying neighborhoods in the process. As the thirteenth century progressed, friars increasingly inserted large conventual complexes within densely inhabited urban space. In Italy in particular they also carved out open areas (piazzas) for preaching. Yet, although it is hard to imagine any medieval city without its mendicant convents, the reconstruction of their presence as a physical, spiritual, economic, and social phenomenon after the systematic and thorough destruction that began as early as the sixteenth-century Reformation remains a challenging task. This essay is an overview of the main themes in recent literature on mendicant build- ings in the Middle Ages 1. A number of books on the architecture of the friars have appeared in the past twenty years. These are dominated by three broad types of analysis. The first focuses on an individual site, either a church alone or a convent as a whole (a few examples are GAI, 1994; BARCLAY LLOYD, 2004; CERVINI, DE MARCHI, 2010; DE MARCHI, PIRAZ, 2011). The second category consists of the survey that covers a region and/or an extended chrono- logical period (DELLWING, 1970, 1990; SCHENKLUHN, 2000, 2003; COOMANS, 2001; VOLTI, 2003; TODENHÖFER, 2010). -

Theology Grades 9-12

DOL: THEOLOGY GRADES 9-12 I. REVELATION OF JESUS CHRIST IN SCRIPTURE DOL: School-wide I.I HOW DO WE KNOW ABOUT GOD? • I.I.1* Identify, in their own life, a personal longing for God and a societal longing for God • I.I.2 Distinguish how God is revealed through natural and divine revelation • I.I.3* Compare and contrast the ways that God is revealed through natural and divine revelation • I.I.4* Justify how sacred scripture is an outgrowth of God’s revelation through Tradition • I.I.5 Explain how Apostolic tradition connects us to the person of Jesus I.II ABOUT SACRED SCRIPTURE. • I.II.1 Characterize the authorship of Scripture as both divine and human • I.II.2 Describe what the Catholic understanding of the inerrancy of Scripture is and what it is not • I.II.3 Utilize Sacred Scripture in a variety of ways for personal and communal prayer • I.II.4 Summarize how the bible came to be I.III UNDERSTANDING SCRIPTURE • I.III.1 Explain the role of the teaching office of the church in the authentic interpretation of Scripture • I.III.2* Apply the four senses of Scripture (literal, allegorical, moral, and anagogical) to their daily lives • I.III.3 Articulate and apply the Church’s criteria for the personal reading of Scripture • I.III.4* Differentiate between religious truth, scientific truth, and historical truth. Explain whythey cannot be in conflict I.IV OVERVIEW OF THE BIBLE • I.IV.1 Identify the major sections of the Old Testament • I.IV.2 Explain how the Old Testament foreshadows the coming of Jesus • I.IV.3* Explain the difference between -

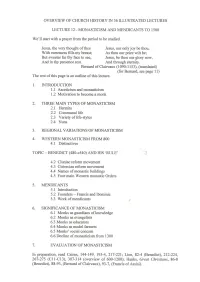

Monasticism to 1500, Mendicant Orders

OVERVIEW OF CHURCH HISTORY IN 36 ILLUSTRATED LECTURES LECTURE 12 - MONASTICISM AND MENDICANTS TO 1500 We'll start with a prayer from the period to be studied. Jesus, the very thought of thee Jesus , our only joy be thou, With sweetness fills my breast; As thou our prize wilt be; But sweeter far thy face to see, Jesus, be thou our glory now, And in thy presence rest. And through eternity. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) , (translated) (for Bernard, see page 11) The rest of this page is an outline of this lecture . 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Asceticism and monasticism 1.2 Motivation to become a monk 2. THREE MAIN TYPES OF MONASTICISM 2.1 Hermits 2.2 Communal life 2.3 Variety of life-styles 2.4 Nuns 3. REGIONAL VARIATIONS OF MONASTICISM 4. WESTERN MONASTICISM FROM 800 4.1 Distinctives TOPIC - BENEDICT (480-c540) AND HIS 'RULE ' 4.2 Cluniac reform movement 4.3 Cistercian reform movement 4.4 Names of monastic buildings 4.5 Four main Western monastic Orders 5. MENDICANTS 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Founders -Francis and Dominic 5.3 Work of mendicants 6. SIGNIFICANCE OF MONASTICISM 6.1 Monks as guardians of knowledge 6.2 Monks as evangelists 6.3 Monks as educators 6.4 Monks as model farmers 6.5 Monks' social concern 6.6 Decline of monasticism from 1300 7. EVALUATION OF MONASTICISM In preparation , read Cairns, 144-149, 193-4, 217-221 ; Lion, 82-4 (Benedict) , 212-224 , 267-275 (Cll-C13) , 307-314 (overview of 600-1200) ; Hanks , Great Christians, 86-8 (Benedict) , 88-93, (Bernard of Clairvaux) , 93-7, (Francis of Assisi). -

The Apostolic Succession of Anthony Alan “Mcpherson” Pearson of the Independent Catholic Church of North America

Old Ca The Apostolic Succession of Anthony Alan “McPherson” Pearson of the Independent Catholic Church of North America Name & Nationality Date & Place of Election Abdication or Death (1) St. Peter the Apostle (Palestinian) 42? Rome 67? Rome Simon, know as peter or Kepha, “the Rock.” Corner of the Church. From Bethseda. Fisherman (2) St. Linus (Italian, Volterra) 67? Rome 78? Rome Student Apostle. Slave or freedman. (3) St. Cletus or Ancletus (Roman) 78? Rome Student Apostle. Freedman 90? Rome (4) St. Clement I (Roman) 90? Rome Student Apostle 99 Crimea (5) St. Evaristus (Greek. Bethlehem) 99? Rome 105? Rome (6) St. Alexander I (Roman) 105? Rome 115? Rome (7) St. Sixtus I (Roman) 115? Rome 125? Rome (8) St. Telesphorus (Greek Anchorite) 125? Rome 136? Rome (9) St. Hygimus (Greek. Athens) 136? Rome Philosopher 140? Rome (10) St. Pius I (Italian. Aquilegia) 140? Rome 155? Rome (11) St. Anicetus (Syrian. Anisa) 155? Rome 166? Rome (12) St. Soter (Italian. Fundi) 166? Rome 175 Rome (13) St. Eleutherius (Greek. Nicopolis) 175? Rome Deacon 189 Rome (14) St. Victor I (African Deacon) 189 Rome 199 Rome (15) St. Zephyrinus (Roman) 199 Rome 217 Rome (16) St. Callistus I (Roman Priest) 217 Rome Slave 222 Rome St. Hyppolitus (Roman Scholar) 217 Rome Anti-pope 235 Rome St. Hyppolitus asserted that Christ was the Son of God and had assumed a human form, rejecting the heresy which said the “God Himself became man through Christ.” Pope Callistus called Hyppolitus a “Two-God Man.” From St. Hyppolitus the Empire that was to precede the coming of the Antichrist was that of Rome. -

Begging Without Shame-Medieval Mendicant Orders Relied On

PHILANTHROPY ‘BEGGING WITHOUT SHAME’ Medieval Mendicant Orders Relied on Contributions FR. THOMAS NAIRN, OFM, PhD he period from the 11th to 13th centuries witnessed the rise of a money economy in Europe. Cities grew and multiplied; more and more land was cultivated, increasing the wealth of landowners; and a new-sprung merchant class made it possible for those T 1 who were not part of the aristocracy to accumulate wealth. Partly in reaction to these changes in the larger Giacomo Todeschini, professor of medi- society, a new form of religious life emerged in eval history at the University of Trieste, Italy, the early 13th century — the so-called men- described the mendicant orders’ absolute poverty dicant orders.2 These religious communities this way: “The choice to be poor was realized in a were different from the great monastic orders series of gestures: abandonment of one’s paternal such as the Benedictines or Cistercians, which house, a wandering life, ragged appearance and were founded hundreds of years earlier. Mem- clothes, manual work as scullery-man and mason, bers of the monastic orders devoted themselves and begging without shame.”4 to prayer, learning and manual labor while liv- The dedication of the mendicant orders to ing and working together within the walls of the “begging without shame” produced a different monastery. Although individual monks took the dynamic from that of monastic orders. Volun- vow of poverty, monastic communities owned tary absolute poverty created an institutional land and goods. Over the centuries, the monas- dependency. The mendicant communities relied teries became powerful centers of education, the on contributions — in other words, they needed healing arts and the preservation of culture, often donors — in order to survive.