Introduction to the Malto Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

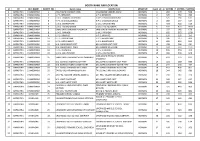

Booth Name and Location

BOOTH NAME AND LOCATION id PC BLK_NAME BOOTH_NO build_name BOOTH_LOC SENSITIVE build_id m_VOTERS f_VOTERS VOTERS 1 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 1 AAGANBADI KENDRA HARLI AAGANBADI KENDRA HARLI NORMAL 1 282 276 558 2 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 2 U.P.S. BIRSODIH U.P.S. BIRSODIH NORMAL 2 376 350 726 3 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 3 U.M.S. CHAMGUDOKHURD U.M.S. CHAMGUDOKHURD NORMAL 3 325 290 615 4 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 4 N.P.S. CHAMGUDOKALA N.P.S. CHAMGUDOKALA NORMAL 4 280 257 537 5 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 5 U.M.S. CHARKIPAHRI U.M.S. CHARKIPAHRI NORMAL 5 493 420 913 6 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 6 U.M.S. DIGTHU GAIDA U.M.S. DIGTHU GAIDA NORMAL 6 539 470 1009 7 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 7 SAMUDAYIK BHAWAN POKDANDA SAMUDAYIK BHAWAN POKDANDA NORMAL 7 337 341 678 8 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 8 U.M.S. PIPRADIH U.M.S. PIPRADIH NORMAL 8 605 503 1108 9 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 9 U.P.S. ARNIYAO U.P.S. ARNIYAO NORMAL 9 139 120 259 10 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 10 U.P.S. BANDACHAK U.P.S. BANDACHAK NORMAL 10 246 217 463 11 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 11 U.P.S. GARAYANDIH U.P.S. GARAYANDIH NORMAL 11 409 404 813 12 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 12 M.S. KANKO EAST PART M.S. KANKO EAST PART NORMAL 12 498 436 934 13 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 13 M.S. KANKO WEST PART M.S. KANKO WEST PART NORMAL 13 594 507 1101 14 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 14 U.P.S. KURMIDIH U.P.S. KURMIDIH NORMAL 14 195 159 354 15 BARKATHA CHANDWARA 15 U.M.S. -

Camscanner 07-06-2020 17.45.18

ftyk xzkeh.k fodkl vfHkdj.k] gtkjhckxA rduhfd lgk;d ¼lgk;d vfHk;ark ds led{k½ ds fjDr in ij fu;qfDr gsrq izkIr vkosnuksa dh izkjafHkd lwph ESSENTIAL QUALIFICATION ADDITIONAL QUALIFICATION OTHER CASTE AFFID B.E./ B.TECH IN CIVIL M.TECH/ P.G.D.C.A./ M.C.A/ MCA MARKS SL. STATE/ CERTIFI AVIT NAME F/H NAME SEX PERMANENT ADDRESS PRESENT ADDRESS D.O.B. CATG. AFTER 5 EXP. REMARKS NO. DISTRI CATE (YES/ TOTAL OBTAINE TOTAL OBTAINE POINTS CT (Y/N) COURSE % GE COURSE % GE NO) MARKS D MARKS MARKS D MARKS LESS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18PGDCA 19 20 21 22 VILLAGE-JARA TOLA, VILLAGE- SOLIYA, PO- B.E. IN MARKSHEE AVINASH LATE NARESH MURRAMKALA, PO PALANI, TALATAND, PS- 1 Male Y 25-11-1995 ST Y CIVIL N N T NOT MUNDA MUNDA +PS+DISTRICT-RAMGARH PATRATU, DISTRICT- ENGG. ATTACHED. 829122 Jharkhand Ramgarh 829119 Jharkhand G.R. HOUSE, SIR SYED G.R. HOUSE, SIR SYED NAGAR, KAJLAMANI ROAD, NAGAR, KAJLAMANI ROAD, B.E. IN MARKSHEE MD GAZNAFER JAMIL AKHTER KISHANGANJ, KISHANGANJ KISHANGANJ, KISHANGANJ 2 Male Y 01-05-1991 GEN - CIVIL N Y T NOT RABBANI RABBANI TOWN, TOWN, ENGG. ATTACHED. PS+BLOCK+DISTRICT- PS+BLOCK+DISTRICT- KISHANGANJ 855107 Bihar KISHANGANJ 855107 Bihar VILL- AMBAKOTHI, VILL- AMBAKOTHI, B.E. IN PRAMOD 3 SURESH RAM Male PO+PS+BLOCK+DISTRICT- PO+PS+BLOCK+DISTRICT- Y 20-03-1982 SC Y CIVIL 8000 5144 64.30 N Y KUMAR LATEHAR 829206 Jharkhand LATEHAR 829206 Jharkhand ENGG. -

Hazaribagh, District Census Handbook, Bihar

~ i ~ € :I ':~ k f ~ it ~ f !' ... (;) ,; S2 ~'" VI i ~ ~ ~ ~ -I fI-~;'~ci'o ;lO 0 ~~i~~s. R m J:: Ov c V\ ~ -I Z VI I ~ =i <; » -< HUm N 3: ~: ;;; » ...< . ~ » ~ :0: OJ ;: . » " ~" ;;; C'l ;!; I if G' l C!l » I I .il" '" (- l' C. Z (5 < ..,0 :a -1 -I ~ o 3 D {If J<' > o - g- .,. ., ! ~ ~ J /y ~ ::.,. '"o " c z '"0 3 .,.::t .. .. • -1 .,. ... ~ '" '"c ~ 0 '!. s~ 0 c "v -; '"z ~ a 11 ¥ -'I ~~ 11 CENSUS 1961 BIHAR DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 14 HAZARIBAGH PART I-INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CENSUS TABLES AND OFFICIAL STATISTICS -::-_'" ---..... ..)t:' ,'t" -r;~ '\ ....,.-. --~--~ - .... .._,. , . /" • <":'?¥~" ' \ ........ ~ '-.. "III' ,_ _ _. ~ ~~!_~--- w , '::_- '~'~. s. D. PRASAD 0 .. THE IlQ)IAJr AD:uJlIfISTBA'X'lVB SEBVlOE Supwtnundent 01 Oen.ua Operatio1N, B'h4r 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, BIHAR (All the Census Publications of this State will bear Vol. no. IV) Central Government Publications PART I-A General Report PART I-B Report on Vital Statistics of Bihar, 1951-60 PART I-C Subsidiary Tables of 1961. PART II-A General Population Tables· PART II-B(i) Economic Tables (B-1 to B-IV and B-VU)· PAR't II-B(ii) Economic Tables (B-V, B-VI, B-VIII and B-IX)* PART II-C Social and Cultural Tables* PART II-D Migration Tables· PART III (i) Household Economic Tables (B-X to B-XIV)* PART III (ii) Household Economic Tables (B-XV to B-XVII)* PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments· PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Table:,* PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribe&* PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Village Surveys •• (Monoglaphs on 37 selected villages) PART VII-A Selected Crafts of Bihar PART VII-B Fairs and Festivals of Bihar PART VIII-A Administration Report on Enumeration * } (Not for sale) PART VIII-B Administration Report on Tabulation PART IX Census Atlas of Bihar. -

Male Female Trans Gender Total DISTRICT

DISTRICT - HAZARIBAG CRS Online Death Registration Report in month of Febuary-2021 Sl. Sub District Registration Unit Name RU Type Registered Events No. Male Female Trans Total gender 1 Barkatha COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS BARKATTA Health 0 1 0 1 2 Hazaribag HAZARIBAGH SADAR HOSPITAL Health 8 14 0 22 3 Keredari COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS KEREDARI Health 1 0 0 1 4 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT BEHRA Panchyat 1 3 0 4 5 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT PANDEYBARA Panchyat 2 1 0 3 6 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT BASARIYA Panchyat 0 1 0 1 7 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT BELA Panchyat 1 1 0 2 8 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT JHAPA Panchyat 5 1 0 6 9 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT BARAHMAURIYA Panchyat 2 0 0 2 10 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT CHAITHI Panchyat 2 1 0 3 11 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT CHAUPARAN Panchyat 1 0 0 1 12 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT CHORDAHA Panchyat 1 1 0 2 13 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT DADPUR Panchyat 2 0 0 2 14 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT DAIHAR Panchyat 3 0 0 3 15 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT JAGDISHPUR Panchyat 3 0 0 3 16 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT GOVINDPUR Panchyat 2 1 0 3 17 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT JABANPUR Panchyat 1 0 0 1 18 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT KARMA Panchyat 1 1 0 2 19 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT SINGHRAWAN Panchyat 2 1 0 3 20 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT MANGARH Panchyat 1 0 0 1 21 Chauparan GRAMA PANCHAYAT TAJPUR Panchyat 1 0 0 1 22 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BHANDARO Panchyat 1 0 0 1 23 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT DHANWAR Panchyat 1 2 0 3 24 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BARHI EAST Panchyat 0 1 0 1 25 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KOLHUKALA Panchyat 2 0 0 2 26 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT -

West Zone Forest Land Sale Report

WEST ZONE FOREST LAND SALE REPORT VENDOR VENDEE FATHER/HUSBAND SL.NO. Anchal Name Mauja Name Thana No Khata No Plot No AREA Type Of Deed Deed No Volum No Page From Page To Book CATEGORY Year VENDOR NAME ADDRESS VENDEE NAME ADDRESS FATHER/HUSBAND NAME NAME Bhaduli Pipradih, Barkagaon, BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99 1108 32 Sale Deed 466 13 319 338 I H_HOLD 2012 Nageshwar Yadav Late Bilat Gope Shanti Devi Dharamnath Mahto ango, barkagaon, hazaribagh 1 Hazaribagh Bhaduli Pipradih, Barkagaon, BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99 1108 32 Sale Deed 467 13 339 358 I H_HOLD 2012 Nageshwar Yadav Late Bilat Gope Shanti Devi Dharamnath Mahto ango, barkagaon, hazaribagh 2 Hazaribagh bhaduli pipradih, barkagaon, ango tola singar saray, barkagaon, BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99 1108 6 Sale Deed 468 13 359 372 I DON 2012 Madheshwar Gope Late Bilat Gope Ganesh Mahto Late Tikan Mahto 3 hazaribagh hazaribagh ango tola ambatola, barkagaon, BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99/77 1108 9 Sale Deed 5813 172 503 518 I R_COM 2013 Md. Imtiyaz Ahmad Md. Karim Punam Devi Sitaram Ango Tola lukaiya, Barkagaon, Hazaribagh 4 hazaribagh Lt. Dhaneshwar G.V.K. Cole (Tokisud) Pvt. BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99 1651 95 Sale Deed 7082 180 473 508 I COMMIND_NH_RD 2009 Most. Nanki Ango, Barkagaon, Hazaribagh C.H. Kailasham C 218, Ashok Nagar, Road No. 2, Ranchi 5 Ganjhu Ltd.(Th-C.H.Dayanand) Lt. Dhaneshwar G.V.K. Cole (Tokisud) Pvt. BADKAGAON ANGO 97 99 1582 82 Sale Deed 7082 180 473 508 I COMMIND_NH_RD 2009 Most. Nanki Ango, Barkagaon, Hazaribagh C.H. Kailasham C 218, Ashok Nagar, Road No. -

DISTRICT - HAZARIBAG CRS Online Death Registration Report in Month of March-2021 Sl

DISTRICT - HAZARIBAG CRS Online Death Registration Report in month of March-2021 Sl. Sub District Registration Unit Name RU Type Registered Events No. Male Female Trans Total gender 1 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BHANDARO Panchyat 2 1 0 3 2 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT DHANWAR Panchyat 1 3 0 4 3 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BARHI EAST Panchyat 0 1 0 1 4 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BARHI WEAST Panchyat 1 0 0 1 5 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BIJAIYA Panchyat 0 1 0 1 6 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KOLHUKALA Panchyat 2 0 0 2 7 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT DULMAHA Panchyat 4 1 0 5 8 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT DAPOK Panchyat 3 2 0 5 9 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KEDARUT Panchyat 1 1 0 2 10 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KARIYATPUR Panchyat 4 1 0 5 11 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT GAURIYAKARMA Panchyat 6 2 0 8 12 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KARSO Panchyat 1 0 0 1 13 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KHODAHAR Panchyat 2 0 0 2 14 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KONRA Panchyat 7 1 0 8 15 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT RANICHUWAN Panchyat 2 0 0 2 16 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT MALKOKO Panchyat 1 0 0 1 17 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BARSOT Panchyat 4 0 0 4 18 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BASARIYA-PANCHMADHAW Panchyat 1 0 0 1 19 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BENDGI Panchyat 1 1 0 2 20 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT RASOIYA DHAMNA Panchyat 3 2 0 5 21 Barkagaon GRAMA PANCHAYAT ANGO Panchyat 3 1 0 4 22 Barkagaon GRAMA PANCHAYAT BADAM Panchyat 2 0 0 2 23 Barkagaon GRAMA PANCHAYAT BARKAGAON MIDDLE Panchyat 6 1 0 7 24 Barkagaon GRAMA PANCHAYAT CHANDAUL Panchyat 1 0 0 1 25 Barkagaon GRAMA PANCHAYAT CHEPAKALA Panchyat 6 2 0 8 26 Barkagaon GRAMA PANCHAYAT CHOPDAR BALIYA Panchyat 1 2 0 3 27 Barkagaon GRAMA -

Towns of India: Status of Demography, Economy, Social Structures, Housing and Basic Infrastructure

Towns of India Status of Demography, Economy, Social Structures, Housing and Basic Infrastructure HSMI – HUDCO Chair – NIUA Collaborative Research 2016 Towns of India Status of Demography, Economy, Social Structures, Housing and Basic Infrastructure HSMI – HUDCO Chair – NIUA Collaborative Research 2016 Foreword An increasing number of people live in small and medium-sized towns in the periphery of large cities as the world completes its process of urban transition. India is no exception to this phenomenon. It is in these towns where national economies are to be built, solutions to global challenges such as inequality and the impacts of climate change are to be addressed, and future generations are to be educated. The reality in India, however, suggests that the small towns are not fully integrated in the urban fabric of the nation. They have enormous backlogs in economic infrastructure, weak human capacity, high levels of under unemployment and unemployment, and extremely weak local economies. However, with their growing numbers – there are more than 2,500 new towns added in the last Population Census– the role of small and medium-sized towns in the national economy will have a significant influence upon the future social and economic development of larger geographic regions. If these towns were better equipped to steer their economic assets and development, the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) could be increased, with significant benefits reducing rural poverty in the hinterlands. This research on small towns, those below 100,000 population, was conducted at the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA), New Delhi, under Phase III of the HUDCO Chair project during the period 2015-16. -

Government of Jharkhand Drinking Water and Sanitation Department

GOVERNMENT OF JHARKHAND DRINKING WATER AND SANITATION DEPARTMENT TENDER NOTICE N0-16 of 2012-13 1 Name of the Department Drinking Water and Sanitation Department, Jharkhand, Ranchi. Superintending Engineer, Drinking Water & Sanitation Circle, 2 Name of the Advertiser Hazaribagh 3 Last date of sale of B.O.Q. Date :- 16.01.2013 Up to 05.00 PM 4 Date and time of receipt of tender Date :- 17.01.2013 Up to 03.30. P.M 5 Date and time of opening of tender Date :- 18.01.2013 AT 11.30 A.M. onwards i) Office of the Superintending Engineer, D.W. & S. Circle, Hazaribagh 6 Place of sale of B.O.Q. ii) Office of the Executive Engineer, D.W. & S. Division, Hazaribagh Name of Office where receipt of 1. Office of the Superintending 7 tender Engineer, D.W. & S. Circle, Hazaribagh A Name of Work:- Construction of Mini Rural Pipe Water Supply Scheme using under NRDWP existing HYDT as source with electricity/Solar operated submersible motor pump, HDPE water stores tanks over pump house, UPVC pipe lines, water recharge pits,etc. including One year operation & maintenance in different site under Drinking Water & Sanitation Division, Hazaribagh during the year 2012-13. Cost of Tender Estimated Earnest Group document, Non- Time of Name of Location Cost money S.N. No. Returnable. Completion (in Rs.) (in Rs.) (in Rs.) Block – Barhi, Panchayat – Barhi, Village- 1 BRH - 1 15,68,500.00 31,500.00 5,000.00 6 Month Barhi, Location- Electric Sub Station Block – Barhi, Panchayat – Dulmuha, 2 BRH - 2 Village- Burhidih, Location- Gov. -

DISTRICT - HAZARIBAG CRS Online Birth Registration Report in Month of Febuary-2021 Registered Events Sl

DISTRICT - HAZARIBAG CRS Online Birth Registration Report in month of Febuary-2021 Registered Events Sl. Sub District Registration Unit Name RU Type Transge No. Male Female Total nder 1 Barhi SUB DIVISIONAL HOSPITAL, BARHI Health 11 9 0 20 2 Barhi ADD. PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRES DARU Health 6 7 0 13 3 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BARHI WEAST Panchyat 1 1 0 2 4 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BARHI EAST Panchyat 2 3 0 5 GRAMA PANCHAYAT BASARIYA- 5 Barhi Panchyat 2 1 0 3 PANCHMADHAW 6 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BHANDARO Panchyat 1 2 0 3 7 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT DULMAHA Panchyat 2 2 0 4 8 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT DHANWAR Panchyat 2 1 0 3 9 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KARIYATPUR Panchyat 1 0 0 1 10 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT GAURIYAKARMA Panchyat 4 3 0 7 11 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KARSO Panchyat 1 1 0 2 12 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KHODAHAR Panchyat 1 0 0 1 13 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT DAPOK Panchyat 2 2 0 4 14 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KONRA Panchyat 4 0 0 4 15 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BARSOT Panchyat 1 0 0 1 16 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT BENDGI Panchyat 2 3 0 5 17 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT RASOIYA DHAMNA Panchyat 0 2 0 2 18 Barhi GRAMA PANCHAYAT KOLHUKALA Panchyat 1 1 0 2 19 Barkagaon HEALTH SUB CENTER AMBAJIT Health 1 0 0 1 COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS 20 Barkagaon Health 24 17 0 41 BARKAGAON 21 Barkagaon HEALTH SUB CENTER GOSAIN BALIA Health 0 1 0 1 22 Barkagaon HEALTH SUB CENTER JUGRA Health 3 2 0 5 23 Barkagaon HEALTH SUB CENTER JARJARA Health 2 1 0 3 24 Barkagaon HEALTH SUB CENTER MIRZAPUR Health 1 3 0 4 25 Barkagaon HEALTH SUB CENTER NAPO KHURD Health 1 2 0 3 26 Barkagaon HEALTH SUB CENTER PALANDU Health -

![Ftyk Xzkeh.K Fodkl Vfhkdj.K] Gtkjhckxa](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2269/ftyk-xzkeh-k-fodkl-vfhkdj-k-gtkjhckxa-5002269.webp)

Ftyk Xzkeh.K Fodkl Vfhkdj.K] Gtkjhckxa

ftyk xzkeh.k fodkl vfHkdj.k] gtkjhckxA eujsxk ys[kk lgk;d ds fjDr in ij fu;qfDr gsrq izkIr vkosnuksa dh izkjafHkd lwph ESSENTIAL QUALIFICATION ADDITIONAL QUALIFICATION MARKS B.COM. (HONS)/ B.COM. (GEN, AT M.C.A./ P.G.D.C.A./ M.SC. PGDCA CASTE MARKS M.COM B.C.A. LEAST 55% MARKS) AFTER (Computer Science) AFTER 5 AFFID CERTI. SL_ PERMANENT_ADD Other NAMEF/H_NAMESEX PRESENT_ADDRESS D.O.B. CATG. 5 POINTS AVIT ATTA EXP. REMARKS N RESS District LESS POINTS TOTA TOTA TOTA (Y/ N) CHED TOTAL OBTAIN OBTAIN OBTAIN BCA (Y/ N) COURS OBTAINE LESS COURS L COURS L L MARK % GE ED % GE ED % GE COURSE ED % GE AFTER E D MARKS (GEN) E MARK E MARK MARK S MARKS MARKS MARKS PGDCA S S S 10 % 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 PO-Kariyatpur, PS- PO-Kariyatpur, PS- 1 Soni kumari Akhilesh pd mehta Female Ichak, Hazaribagh, Ichak, Hazaribagh, 18-08-1997 BC2 NO B.COM 800 539 67.38 NO YES NO Jharkhand, 825402, Jharkhand, 825402, VILLAGE-Beltu, PS- VILLAGE-Beltu, PS- Ramchandra Kandaber, PS- Kandaber, PS- 2 Jagdish Saw Male 17-02-1997 BC-I NO B.COM 2400 1491 62.13 NO YES NO kumar Keredari, Keredari, HAZARIBAG HAZARIBAG CHANDOUL, CHANDOUL, PO+PS- B.COM PO+PS- MARKSHE SHYAM DILCHAND BARKAGAON, 3 Male BARKAGAON, 04-03-1988 SC NO B.COM 800 455 56.88 MCOM 1600 1048 65.50 NO YES NO ET NOT SUNDAR DAS RAM HAZARIBAG, HAZARIBAG, ATTACHE Jharkhand, 825311 Jharkhand, 825311 D. -

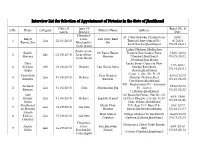

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Jharkhand

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Jharkhand Date Of Area Of Enrol. No. & S.No. Name Category Father's Name Address App'n Practice Date Dhanbad- At- Uday Bhawan Dhaiya Near 1885- Ranjit Cum- Late Uday Kant 1 Gen 23.04.2018 Trimurti Appertment Po- A/2001 Kumar Jha Kenduadih- Jha Ism,Dhanbad,Jharkhand Dt.09.05.01 Cum-Jagata Lodna Nadipar Madhuban Jharia-Cum- Rajesh Sri Kanu Hajam Kujama Basti Lodna Tisra 1503/2002 2 Gen 03.06.2018 Jorapokhar- Sharma Sharma Dhanbad Jharkhand Dt.09.09.02 Cum-Sindri ,Dhanbad,Jharkhand Hare Lucky Sweet Opposite New 117/2001 3 Krishna Obc 19.08.2018 Ranchi Late Binod Sahu Market Ratu Road Dt.14.06.01 Gupta ,Ranchi,Jharkhand Camp-1, Qtr. No. D-19 Vijay Nath Hari Nandan 4092/2005 4 Gen 31.08.2018 Bokaro Marafari Bokaro Steel Kunwar Kunwar Dt.12.05.05 City,Bokaro,Jharkhand Vill - Baghraibera Po - Satanpur Archana 1936/2003 5 Gen 31.08.2018 Chas Manmohan Jha Ps - Sector Kumari Dt.26.02.03 12,Bokaro,Jharkhand Ajay Sri Rajendra Palace, Flat No. 03 469/1988 6 Kumar Gen 31.08.2018 Bokaro Jagdish Prasad 1st Floor Bhojpur Colony, Po.Ps- Dt.29.04.88 Sinha Chas ,Bokaro,Jharkhand Madhusud Murli Dhar Vill- Rejo P.O- Bana P.S- 184/2007 7 Gen 14.09.2018 Garhwa an Sharma Sharma Meral,Garhwa,Jharkhand Dt.28.02.07 Awadh Ram Mahal Village Mahupi Po Garhwa Ps 3669/2005 8 Kishore Gen 15.09.2018 Garhwa Chaubey Garhwa,Garhwa,Jharkhand Dt.07.02.05 Chaubey Dhanbad- Manaitand Chhat Talab Rajpati Anjani Cum- Late.Janardan 689/2010 9 Gen 16.09.2018 Saw Sinha Kenduadih- Prasad Dt.28.08.10 Colony,Dhanbad,Jharkhand Cum-Jagata Raju At B.D Gutgutia Road, Hajigali Jagat Narayan 1253/1999 10 Prasad Obc 24.12.2018 Madhupur Po Madhupur Ps Shaw Dt.09.04.99 Gupta Madhupur,Deoghar,Jharkhand Near Canal. -

Booth List AC Wise Sr. No District/PC AC PS No. PS Name PSL No. 1 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 1 Aganbari Kendra Harali 1 2 360-Haza

Booth List AC Wise Sr. No District/PC AC PS No. PS Name PSL No. 1 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 1 Aganbari Kendra Harali 1 2 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 2 Upgraded Middle School Birsodih 2 3 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 3 Upgraded Middle School- Chamgudokhurd 3 4 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 4 N.P.S. Chamgudokala 296 5 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 5 Upgraded Middle School Charkipahari 4 6 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 6 Upgraded Middle School digthu Gainda 5 7 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 7 Community Hall- Pokdanda 6 8 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 8 Upgraded Middle School Pipradih 7 9 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 9 U.P.S Arniyaon 283 10 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 10 Upgraded Primary School Bandachak 8 11 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 11 Upgraded Primary School Garayadih 9 12 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 12 Middle School Kanko (East Part) 10 13 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 13 Middle School Kanko(West Part) 10 14 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 14 Upgraded Primary School Kurmidih 11 15 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 15 Upgraded Middle School Jolahakarma 12 16 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 16 Community Hall- Chhotaki Dhamray 13 17 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 17 Middle School Badaki Dhamray (East) 14 18 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 18 M.S. Badki Dhamray- S.Part 14 19 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 19 Middle School Badaki Dhamray (West) 14 20 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 20 Tahsil Kachahari- Manjhagawan 15 21 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 21 Aditional Health centre- Simariya 16 22 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 22 Middle School Kanti E.Part 17 23 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 23 M.S. Kanti- W.Part 17 24 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 24 Panchayat Bhavan Kanti 18 25 360-Hazaribagh Barkatha 25 D.