Dissertation Ille.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy

The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight against White Supremacy Jeffrey B. Perry Epigraph (In 22 parts) “The King James version of the Bible . does not contain the word ‘race’ in our modern sense . as late as 1611 our modern idea of race had not yet arisen.” – Hubert Harrison “World Problems of Race,” 1926 “When the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, there were no ‘white’ people there; nor, according to the colonial records, would there be for another sixty years.” – Theodore W. Allen The Invention of the White Race, Vol. 1, 1994 (Written after searching through 885 county-years of Virginia’s colonial records) “In the latter half of the seventeenth century, [in] Virginia and Maryland, the tobacco colonies . Afro-American and European-American proletarians made common cause in this struggle to an extent never duplicated in the three hundred years since.” – Theodore W. Allen Class Struggle and the Origin of Racial Slavery: The Invention of the White Race, 1975 “ . the plantation bourgeoisie established a system of social control by the institutionalization of the ‘white’ race whereby the mass of poor whites was alienated from the black proletariat and enlisted as enforcers of bourgeois power.” – Theodore W. Allen Class Struggle and the Origin of Racial Slavery: The Invention of the White Race, 1975 Jeffrey B. Perry 2 “ . the record indicates that laboring-class European-Americans in the continental plantation colonies showed little interest in ‘white identity’ before the institution of the system of ‘race’ privileges at the end of the seventeenth century.” – Theodore W. -

Bamcinématek Presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 Days of 40 Genre-Busting Films, Aug 5—24

BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 days of 40 genre-busting films, Aug 5—24 “One of the undisputed masters of modern genre cinema.” —Tom Huddleston, Time Out London Dante to appear in person at select screenings Aug 5—Aug 7 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Jul 18, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, August 5, through Wednesday, August 24, BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, a sprawling collection of Dante’s essential film and television work along with offbeat favorites hand-picked by the director. Additionally, Dante will appear in person at the August 5 screening of Gremlins (1984), August 6 screening of Matinee (1990), and the August 7 free screening of rarely seen The Movie Orgy (1968). Original and unapologetically entertaining, the films of Joe Dante both celebrate and skewer American culture. Dante got his start working for Roger Corman, and an appreciation for unpretentious, low-budget ingenuity runs throughout his films. The series kicks off with the essential box-office sensation Gremlins (1984—Aug 5, 8 & 20), with Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates. Billy (Galligan) finds out the hard way what happens when you feed a Mogwai after midnight and mini terrors take over his all-American town. Continuing the necessary viewing is the “uninhibited and uproarious monster bash,” (Michael Sragow, New Yorker) Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990—Aug 6 & 20). Dante’s sequel to his commercial hit plays like a spoof of the original, with occasional bursts of horror and celebrity cameos. In The Howling (1981), a news anchor finds herself the target of a shape-shifting serial killer in Dante’s take on the werewolf genre. -

Paul Shottner Eta' 45/50 Provenienza

PAUL SHOTTNER ETA’ 45/50 PROVENIENZA Roma FILM (selection) Reves A Vendre Man In Gallery Lola Peploe/ Wildside Pictures Goldfish Starter Kit Joe Phil Miller/ Y Films The Palm Reader Robin Jonathan Bentovim/ Indivision Films The Image Thief Weston/ Supporting Corin Sworn/ Film & Video Umbrella Why did you buy me plastic Leonard/Lead Phil Miller/ Y Films flowers? Girlfriend Experience Pimp/ Supporting Ileana Pietrobruno/ Cineworks The Men’s Room Seth/ Lead David Crossman/ Quest Productions Part Time Mugger Mark Smith/ Lead Paul Shottner/ Oil Film Karma Cowboy Narrator Sonja Heiss & Vanessa Van Houten/ Komplizen Film/ REM Doku Holdin’ On Killer/ Lead Frank Feiler/ Atomic Film Production Mimic NYPD Officer/ Supporting Guillermo Del Toro/ Dimension Films Turkey Day Luzio/ Supporting Steven Sorentos/ Mustang Films Volcano National Guard/ Supporting Mick Jackson/ 20th Century Fox The Black Widow The Man/ Lead Andrew Blackwell/ Long And Winding Road Productions Sullivan Street Alan Barrow/ Lead Jesse E. Evans/ Big Dawg Productions The Prodigal Son Carl/ Lead Lamia Joreige/ Djinn House Productions TELEVISION (Selection) Zwei Brueder - Tod Im See Pater Steinhauer/ Principal Lars Becker/ ZDF The Second Civil War Journalist/ Supporting Joe Dante/ HBO Films Melrose Place Counter Clerk/ Supporting Charlie Corell/ Spelling TV/ Fox THEATER (Selection) A Hatful Of Rain Polo Pope/ Lead Simon Longmore/ VADA D. Centre The Usual Suspects Fred Fenster/ Principal 2 Way Mirror Prod./ UK & Ireland Tour In Transit Gregorio Kapelov/ Principal Sahar Thompson/ Open Space Theatre Nothing Zed/ Lead Paul Shottner/ Man In The Moon Theatre Les Liaisons Dangereuses Comte De Valmont/ Lead Irma Saundrey/ Strasberg Theatre Fool For Love Eddie/ Lead Irma Saundrey/ Strasberg Theatre Danny & The Deep Blue Sea Danny/ Lead Michael Margotta/ Strasberg Theatre COMMERCIALS & VOICE OVER List available upon request. -

Our Housing Mess... and What Can Be Done About It

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 102 229 UD 014 553 AUTHOR Blake, Peter TITLE Our Housing Mess... And What Can Be Done About It. INSTITUTION American Jewish Committee, New York, N.Y. Inst. of Human Relations. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 76p. AVAILABLE FROM Inst. of Human Relations Press, 165 E. 56 St., New York, New York 10022 ($1.25) EDIn PRICE 1,110-$0.76 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *City Problems; Depressed Areas (Geographic); Economically Disadvantaged; Federal Government; Federal Programs; Government Role; Housing Industry; *Housing Needs; Housing Patterns; Inner City; *Low Rent Housing; Policy Formation; Political Issues; *Public Policy; Real Estate ABSTRACT The housing crisis in the United States isprimarily urban. Unlike areas of urban blight, rural alums are notslums of despair by any means. "Slums of despair" is a term used in a receit study of urban life to describe those areas in someof our inner cities whose inhabitants feel they are utterly trapped--thatthey stand little chance of improving their lot. In thestudy, these desperate regions were contrasted with so-called "slumsof hope," where there was some visible evidence that government orthe community was committed to building new housing orrehabilitating what existed, as well as to creating jobs. This bookis concerned with the ways in which America's hopeless slumsmight be turned into healthy communities. In city after city, the reductionof housing stock has far outstripped the total constructionof new housing. The reasons for this erosion ofbadly needed low-rent housing are complex. Housing subsidies--which means,primarily, subsidies for land acquisition, mortgage interest and rent--areabsolutely essential if new housing is to be created to meet theneeds of low-income families. -

The Cretaceous Geology of the East Texas Basin Ronald D

Thesis Abstracts thinking is more important than elaborate FRANK CARNEY, PH.D. PROFESSOR OF GEOLOGY BAYLOR UNIVERSITY 1929-1934 Objectives of Geological Training at Baylor The training of a geologist in a university covers but a few years; his education continues throughout his active life. The purposes of train ing geologists at Baylor University are to provide a sound basis of understanding and to foster a truly geological point of view, both of which are essential for continued professional growth. The staff considers geology to be unique among sciences since it is primarily a field science. All geologic research in cluding that done in laboratories must be firmly supported by field observations. The student is encouraged to develop an inquiring ob jective attitude and to examine critically all geological concepts and principles. The development of a mature and professional attitude toward geology and geological research is a principal concern of the department. Cover: Trinity Group isopach map illustrating depositional trends of Trinity rocks. (From French) THE BAYLOR PRINTING SERVICE WACO, TEXAS BAYLOR GEOLOGICAL STUDIES BULLETIN NO. 52 THESIS ABSTRACTS These abstracts are taken from theses written in partial fulfillment of degree requirements at Baylor University. The original, unpublished versions of the theses, complete with appendices and bibliographies, can be found in the Ferdinand Roemer Library, Department of Geology, Baylor University, Waco, Texas. BAYLOR UNIVERSITY Department of Geology Waco, Texas Fall Baylor Geological Studies EDITORIAL STAFF Janet L. Burton, Editor O. T. Hayward, Ph.D., Advisor, Cartographic Editor Stephen I. Dworkin, Ph.D. general and urban geology and what have you geochemistry, diagenesis, and sedimentary petrology Joe C. -

James (Jim) B. Simms

February 2013 1 I Salute The Confederate Flag; With Affection, Reverence, And Undying Devotion To The Cause For Which It Stands. From The Adjutant The General Robert E. Rodes Camp 262, Sons of Confederate Veterans, will meet on Thursday night, January 10, 2013. The meeting starts at 7 PM in the Tuscaloosa Public Library Rotary Room, 2nd Floor. The Library is located at 1801 Jack Warner Parkway. The program for February will be DVD’s on General Rodes and one of his battles. The Index of Articles and the listing of Camp Officers are now on Page Two. Look for “Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp #262 Tuscaloosa, AL” on our Facebook page, and “Like” us. James (Jim) B. Simms The Sons of Confederate Veterans is the direct heir of the United Confederate Veterans, and is the oldest hereditary organization for male descendants of Confederate soldiers. Organized at Richmond, Virginia in 1896; the SCV continues to serve as a historical, patriotic, and non-political organization dedicated to ensuring that a true history of the 1861-1865 period is preserved. Membership is open to all male descendants of any veteran who served honorably in the Confederate military. Upcoming 2013 Events 14 February - Camp Meeting 13 June - Camp Meeting 14 March - Camp Meeting 11 July - Camp Meeting 11 April - Camp Meeting August—No Meeting 22-26 - TBD - Confederate Memorial Day Ceremony Annual Summer Stand Down/Bivouac 9 May - Camp Meeting 12 September - Camp Meeting 2 Officers of the Rodes Camp Commander David Allen [email protected] 1st Lieutenant John Harris Commander -

Ending Civil Wars: Constraints & Possibilities

Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Winter 2018 Ending Civil Wars: Constraints & Possibilities Karl Eikenberry & Stephen D. Krasner, guest editors with Francis Fukuyama Tanisha M. Fazal · Stathis N. Kalyvas Charles T. Call & Susanna P. Campbell · Lyse Doucet Thomas Risse & Eric Stollenwerk · Clare Lockhart Tanja A. Börzel & Sonja Grimm · Steven Heydemann Seyoum Mesfin & Abdeta Dribssa Beyene Nancy E. Lindborg & J. Joseph Hewitt Richard Gowan & Stephen John Stedman Sumit Ganguly · Jean-Marie Guéhenno Introduction Karl Eikenberry & Stephen D. Krasner The essays that make up this and the previous issue of Dædalus are the culmination of an eighteen-month American Academy of Arts and Sciences project on Civil Wars, Violence, and International Respons- es. Project participants have examined in depth the KARL EIKENBERRY, a Fellow of the intellectual and policy disagreements over both the American Academy since 2012, is risks posed by intrastate violence and how best to the Oksenberg-Rohlen Fellow and Director of the U.S.-Asia Security treat it. Initiative at Stanford University’s The Fall 2017 issue, “Civil Wars & Global Disorder: Asia-Pacific Research Center. He Threats & Opportunities,” examines the nature and served as the U.S. Ambassador to causative factors of civil wars in the modern era, the Afghanistan and had a thirty-five- security risks posed by high levels of intrastate vio- year career in the United States lence, and the challenges confronting external actors Army, retiring with the rank of lieutenant general. He codirects intervening to end the fighting and seek a political set- the Academy’s project on Civil tlement. It also explains the project’s aims, method- Wars, Violence, and International ologies, and international outreach program.1 Responses. -

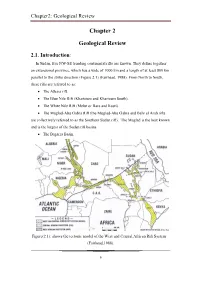

Chapter2: Geological Review

Chapter2: Geological Review Chapter 2 Geological Review 2.1. Introduction: In Sudan, five NW-SE trending continental rifts are known. They define together an extensional province, which has a wide of 1000 km and a length of at least 800 km parallel to the strike direction (Figure 2.1) (Fairhead, 1988). From North to South, these rifts are referred to as: The Atbara rift. The Blue Nile Rift (Khartoum and Khartoum South). The White Nile Rift (Melut or Bara and Kosti). The Muglad-Abu Gabra Rift (the Muglad-Abu Gabra and Bahr el Arab rifts are collectively referred to as the Southern Sudan rift). The Muglad is the best known and is the largest of the Sudan rift basins. The Bagarra Basin. Figure(2.1): shows the tectonic model of the West and Central African Rift System (Fairhead,1988). 6 Chapter2: Geological Review In the northwest, the Sudan rift basins terminate along the transcurrent fault zone in continental scale, the Central African Shear Zone (Figure 2.1). The Central African Shear Zone is envisioned to link the Sudan rift basins with the Lower and Upper Cretaceous rift basins in Chad and Niger (Fairhead,1988). The south-eastern terminations of the Sudan rifts are more complex (Schull 1988). 2.2. Muglad Basin: The Muglad basin is rift basin of Meso-cenozoic, which caused by the shear zone of middle-Africa and developed on the firm basement of Precambrian(Vail, 1978; Whiteman, 1971). There are three superimposed rift formations of different periods in Muglad area since Early Cretaceous(Fairhead, 1988). The first one is Abu Gabra Fm - Bentiu Fm of Lower Cretaceous, the second one is the Darfour group of Upper Cretaceous–Paleocene of Paleogene, and the third is Eocene of paleogene– Neogene. -

Seasonally Variant Stable Isotope Baseline Characterisation of Malawi’S Shire River Basin to Support Integrated Water Resources Management

water Article Seasonally Variant Stable Isotope Baseline Characterisation of Malawi’s Shire River Basin to Support Integrated Water Resources Management Limbikani C. Banda 1,*, Michael O. Rivett 2, Robert M. Kalin 2 , Anold S. K. Zavison 1, Peaches Phiri 1, Geoffrey Chavula 3, Charles Kapachika 3, Sydney Kamtukule 1, Christina Fraser 2 and Muthi Nhlema 4 1 Ministry of Irrigation and Water Development, Tikwere House, Private Bag 390, Lilongwe 3, Malawi; [email protected] (A.S.K.Z.); [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (S.K.) 2 Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow G1 1XJ, UK; [email protected] (M.O.R.); [email protected] (R.M.K.); [email protected] (C.F.) 3 Departments of Civil Engineering and Land Surveying, University of Malawi—The Polytechnic, Private Bag 303, Blantyre 3, Malawi; [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (C.K.) 4 BASEflow, P.O. Box 30467, Blantyre, Malawi; muthi@baseflowmw.com * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 February 2020; Accepted: 8 May 2020; Published: 15 May 2020 Abstract: Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) is vital to the future of Malawi and motivates this study’s provision of the first stable isotope baseline characterization of the Shire River Basin (SRB). The SRB drains much of Southern Malawi and receives the sole outflow of Lake Malawi whose catchment extends over much of Central and Northern Malawi (and Tanzania and Mozambique). Stable isotope (283) and hydrochemical (150) samples were collected in 2017–2018 and analysed at Malawi’s recently commissioned National Isotopes Laboratory. -

Of Frank Gehry's Los Angeles Katherine Shearer Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 The "Postmodern Geographies" of Frank Gehry's Los Angeles Katherine Shearer Scripps College Recommended Citation Shearer, Katherine, "The "Postmodern Geographies" of Frank Gehry's Los Angeles" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 1031. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1031 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE “POSTMODERN GEOGRAPHIES” OF FRANK GEHRY’S LOS ANGELES BY KATHERINE H. SHEARER SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR GEORGE GORSE PROFESSOR BRUCE COATS APRIL 21, 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I wish to thank my primary reader, Professor George Gorse. In the spring of my sophomore year, I took Professor Gorse’s class “Modern Architecture and Sustainability,” during which I became enthralled in the subject by his unparalleled passion for and poetic articulation of architectural history. Having been both his student and advisee, I am eternally grateful for the incredible advice, challenging insights, and jovial encouragement that Professor Gorse has always provided. I will also forever be in awe of Professor Gorse’s astonishing mental library and ability to recall entire names of art historical texts and scholars at the drop of a hat. I would also like to thank my secondary reader, Professor Bruce Coats, who made himself available to me and returned helpful revisions even while on sabbatical. -

Kinematics of the South Atlantic Rift

Manuscript prepared for Solid Earth with version 4.2 of the LATEX class copernicus.cls. Date: 18 June 2013 Kinematics of the South Atlantic rift Christian Heine1,3, Jasper Zoethout2, and R. Dietmar Muller¨ 1 1EarthByte Group, School of Geosciences, Madsen Buildg. F09, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 2Global New Ventures, Statoil ASA, Forus, Stavanger, Norway 3formerly with GET GME TSG, Statoil ASA, Oslo, Norway Abstract. The South Atlantic rift basin evolved as branch of 35 lantic domain, resulting in both progressively increasing ex- a large Jurassic-Cretaceous intraplate rift zone between the tensional velocities as well as a significant rotation of the African and South American plates during the final breakup extension direction to NE–SW. From base Aptian onwards of western Gondwana. While the relative motions between diachronous lithospheric breakup occurred along the central 5 South America and Africa for post-breakup times are well South Atlantic rift, first in the Sergipe-Alagoas/Rio Muni resolved, many issues pertaining to the fit reconstruction and 40 margin segment in the northernmost South Atlantic. Fi- particular the relation between kinematics and lithosphere nal breakup between South America and Africa occurred in dynamics during pre-breakup remain unclear in currently the conjugate Santos–Benguela margin segment at around published plate models. We have compiled and assimilated 113 Ma and in the Equatorial Atlantic domain between the 10 data from these intraplated rifts and constructed a revised Ghanaian Ridge and the Piau´ı-Ceara´ margin at 103 Ma. We plate kinematic model for the pre-breakup evolution of the 45 conclude that such a multi-velocity, multi-directional rift his- South Atlantic. -

I\Fit/WHOI Join\1Iro~ in Oce~Ography Department Ofearth,Atmospheric, & Planetary Sciences, MIT Certified By: __' ' ' Leigh H

THERMAL AND MECHANICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE EAST AFRICAN RIFT SYSTEM by Cynthia J. Ebinger B.S. Geology, Duke University (1982) S.M. Geophysics, Massachusetts Institute ofTechnology (1986) Submitted to the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, & Planetary Sciences In Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree of Doctor ofPhilosophy at the Massachusetts Institute ofTechnology and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution May, 1988 ©Cynthia J. Ebinger The author hereby grants MIT and WHOI pennission to reproduce and distiif»itelYl.ib1W.b: copies ofthis thesis in whole or in part. Signature of Author: --+J~------l i\fIT/WHOI Join\1iro~ in Oce~ography Department ofEarth,Atmospheric, & Planetary Sciences, MIT Certified by: __' ' ' _ Leigh H. Royden, Thesis Supervisor 1 Twas brillig, and the slithy toves, Did gyre and gymbol in the wabe. All mimsy were the borogroves, And the momeraths outgrabe. Beware the Jabberwock, my son, The claws that catch, the jaws that bite. Beware the Jub-Jub bird and shun Thefrumious Bandersnatch. He took his vorpal sword in hand, Long time the maxomefoe he sought, And rested he by a tum-tum tree, And stood a while in thought. And as an offish thought he stood, The Jabberwock, with eyes aflame, Came whiffling through the tulgy wood. It burbled as it came. One-two, one-two, and through and through, The vorpal blade went snicker-snack. He left it dead, and with its head, He went gallumphing back. And hast thou slain the Jabberwock? Come into my arms my beamish boy. Ohfrabjous day, Calloo-callay. He chortled in his joy. Twas brillig and the slithy toves Did gyre and gymbol in the wabe.