Dissertation Fracking and Goldilocks Federalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 166 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JULY 29, 2020 No. 134 Senate The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was Our two countries, as you know, have the institutions of American life can- called to order by the President pro a centuries-old relationship. That rela- not stay totally shut down until our tempore (Mr. GRASSLEY). tionship will be further strengthened race for a vaccine hits the finish line. f by a comprehensive deal that presents Our Nation needs to smartly and economic opportunities for our farm- safely reopen while keeping up the PRAYER ers, our manufacturers, and our service medical battle. We need to get kids The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- providers to the benefit of both sides of safely back to school and adults safely fered the following prayer: the Atlantic. back to work without losing ground in Eternal God, You have taken care of I will continue to insist that an the healthcare fight. us in the years that have gone. We agreement reached between our two The coronavirus does not care that honor You for Your glory and strength. countries will allow us to reach our full we are divided. The coronavirus will May we place our hope in You and potential as trading partners, particu- not care if Washington Democrats de- never forget that You can also sustain larly when it comes to agricultural cide it suits their partisan goals to let us in the future. -

Eleni Kounalakis (Lt. Governor) Josh Harder (U.S

California Gavin Newsom (Governor) Eleni Kounalakis (Lt. Governor) Josh Harder (U.S. House, CA-10) TJ Cox (U.S. House, CA-21) Katie Hill (U.S. House, CA-25) Katie Porter (U.S. House, CA-45) Harley Rouda (U.S. House, CA-48) Mike Levin (U.S. House, CA-49) Ammar Campa-Najjar (U.S. House, CA-50) Buffy Wicks (State Assembly, District 15) Colorado Jared Polis (Governor) Dianne Primavera (Lt. Governor) Phil Weiser (Attorney General) Jena Griswold (Secretary of State) Tammy Story (State Senate, District 16) Jessie Danielson (State Senate, District 20) Brittany Pettersen (State Senate, District 22) Faith Winter (State Senate, District 24) Dylan Roberts (State House, District 26) Dafna Michaelson Jenet (State House, District 30) Shannon Bird (State House, District 35) Rochelle Galindo (State House, District 50) Julie McCluskie (State House, District 61) Georgia Stacey Abrams (Governor) Sarah Riggs Amico (Lt. Governor) Matthew Wilson (State House, District 80) Shelly Hutchinson (State House, District 107) Illinois J.B. Pritzker (Governor) Juliana Stratton (Lt. Governor) Kwame Raoul (Attorney General) Sean Casten (U.S. House, IL-6) Brendan Kelly (U.S. House, IL-12) Lauren Underwood (U.S. House, IL-14) Iowa Deidre DeJear (Secretary of State) Tim Gannon (Secretary of Agriculture) Kristin Sunde (State House, District 42) Jennifer Konfrst (State House, District 43) Eric Gjerde (State House, District 67) Laura Liegois (State House, District 91) Maine Louis Luchini (State Senate, District 7) Laura Fortman (State Senate, District 13) Linda Sanborn (State Senate, District 30) Nevada Jacky Rosen (U.S. Senate) Susie Lee (U.S. House, NV-3) Steven Horsford (U.S. -

State Election Results, 2005

Official Publication of the Abstract of Votes Cast for the 2005 Coordinated 2006 Primary 2006 General To the Citizens of Colorado: The information in this abstract is compiled from material filed by each of Colorado’s sixty- four County Clerk and Recorders. This publication is a valuable tool in the study of voting patterns of Colorado voters during the 2005 Coordinated, 2006 Primary, and 2006 General Election. As the State’s chief election officer, I encourage the Citizens of Colorado to take an active role in our democratic process by exercising their right to vote. Mike Coffman Colorado Secretary of State Table of Contents GLOSSARY OF ABSTRACT TERMS .............................................................................................. 4 DISCLAIMER ......................................................................................................................... 6 DIRECTORY .......................................................................................................................... 7 United States Senators .........................................................................................................................7 Congressional Members .......................................................................................................................7 Governor ..........................................................................................................................................7 Lieutenant Governor ...........................................................................................................................7 -

MEET the NATION's NEW SECONDS-IN-COMMAND from the National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA)

Subscribe Past Issues Trans Mark the Dates NOW: Nov. 28 - 30, 2018, in VA; March 27 -29, 2019 in DC; & July 17 - 19, 2019, in Delaware. November 12, 2018 MEET THE NATION'S NEW SECONDS-IN-COMMAND from the National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA) The NLGA welcomes 22 new members to the ranks of the seconds-in-command in the states, with at least three additional new members arriving by the new year. The NLGA brings engaged leaders together. All newly elected members are invited to the NLGA Meeting in Alexandria, Virginia, November 28 - 30, 2018. Visit www.nlga.us or contact [email protected] NOW to make arrangements. Registrations are due next Monday. LT. GOVERNOR-ELECT WILL AINSWORTH, ALABAMA (R) Lt. Governor-elect Will Ainsworth served in the State House since 2014. He turned a passion for hunting and fishing into the Dream Ranch, one of the most recognized sportsmen’s lodges in the U.S., and he founded the Tennessee Valley Hunting and Fishing Expo. Elected independently of the Governor. Statutory duties of Alabama lieutenant governor. LT. GOVERNOR-ELECT KEVIN MEYER, ALASKA (R) Lt. Governor-elect Kevin Meyer has a long public service career. He was elected to the Anchorage Assembly, the State House of Representatives, and the Alaska State Senate and held various leadership positions. He is now procurement coordinator for ConocoPhillips. Elected on a ticket with the Governor. Statutory duties of Alaska lieutenant governor. SEC. OF STATE-ELECT STEVE GAYNOR (R) Secretary of State-elect Steve Gaynor is the gubernatorial successor of Arizona. He has owned printing businesses in California, Colorado, and Arizona. -

FORECAST 2014 Rebound in Commercial Real Estate to Continue by JOSHUA LINDENSTEIN County

$1 SCHOOL GUIDE BANKING/FINANCE Expansion in works Sunflower Bank at Dawson School enters local market 13A 17A Volume 33 Issue 1 | Jan. 17-30, 2014 COMMERCIAL RESIDENTIAL RETAIL Developer REAL ESTATE REAL ESTATE “Sales are “We’re not “The general embarks on expected to projecting any consensus is improve at the big slides in that things $180 million Twenty Ninth 2014 or 2015.” look quite Street shopping optimistic.” multiuse plan KATE HONEA district in Boul- LYNDA GIBBONS RYAN McMAKEN spokeswoman, communications Sutherlands site sits president/ Twenty Ninth Street der throughout director/economist managing broker, 2014.” in transit-village area Gibbons-White Inc. Colorado’s Division of Housing BY JOSHUA LINDENSTEIN [email protected] CYBERSECURITY BOULDER —Real estate devel- opment firm ElementProperties LLC “Many and Sopher Architects LLC submit- enterprises FORECAST ted concept plans with the city of Boulder recently on a proposed rede- are not yet velopment of the former Sutherlands prepared to Lumber Co. site that could cost up to $180 million. respond to 2014 The plans call for 680,000 square emerging feet of building space, including room RICK DAKIN The Boulder County Business Report asked people in for apartments, office, retail and res- chief security (cybersecurity) taurant uses as well as a 140-room seven key industires what they expect in 2014. boutiquestyle hotel. There will also strategist, risks.” Coalfire Systems Inc. Stories begin on 6A. be a large public plaza that could someday serve as a train platform for a FasTracks commuter rail stop. Dubbed Spark — short for Suther- land Park in homage to the longtime TECHNOLOGY BANKING HEALTH CARE owners of the site — the develop- ment will sit on roughly eight acres. -

CML Newsletter (ISSN 7439903) Is Published and Grow Their Workforces

Newsletter Vol. 46, No. 5, February 28, 2020 Introducing the Colorado Health Insurance Option By Colorado Lt. Gov. Dianne Primavera we have already made significant progress. pharmacy rebates on to consumers through As policymakers, we should be proud of But health care costs will not continue to premium savings, and bringing some sanity the progress we have made over the past go down on their own. We need to keep to out-of-control prices at mega hospital decade to expand access to health care. By working at it. systems while protecting independent, rural, expanding Medicaid and setting up a health That is why we are working with the and critical access hospitals. exchange — also known as the individual legislature to develop a Colorado Health We estimate that this proposal — which market — we have been able to cut Colorado’s Insurance Option to help reduce costs will be offered on the state’s individual uninsured rate from 16% to 6.5%. But even more. This proposal will offer a more market and eventually also on the small-group Coloradans still struggle to afford care. One in affordable plan by reducing insurance market — will save Coloradans an estimated five Coloradans forgo needed health care due company administrative costs, passing 7%–19% on their premiums. to cost, and one in three are unable to afford their prescription drugs. As a four-time cancer survivor, I was lucky to beat cancer without going broke in the process. But it should not come down to luck. Everyone should be able to afford the care they need. -

2021 NLGA Members Bio Book

ALABAMA Lt. Governor Will Ainsworth Lieutenant Governor Will Ainsworth is a father, husband, and small business owner from Marshall County. Prior to entering public service, he worked as a youth pastor at Albertville’s Grace Fellowship Church and was a co-founder of Dream Ranch, one of the most recognized hunting and fishing lodges in the United States. He currently operates the annual Tennessee Valley Hunting and Fishing Expo, which draws more than 20,000 attendees each year. In 2014, Lt. Gov. Ainsworth felt the call to serve his community through elected office and won a seat in the Alabama House of Representatives, where he was a champion of public education, farming, and family values issues. Keeping a self-imposed legislative term limit promise, Ainsworth declared his candidacy for lieutenant governor in 2018 and received the most votes of any candidate for constitutional office on the general election ballot. Ainsworth, who is committed to providing quality public education to Alabama’s schoolchildren, is a strong supporter of the state’s nationally-recognized “First Class” prekindergarten program, which provides young learners with the skills and foundational knowledge necessary to excel in their K – 12 education. Focusing his efforts as lieutenant governor on improving workforce development so that Alabamians may fill and retain long-lasting, well-paying, 21st Century jobs, he also works to promote policies that allow both new and existing industries to expand in Alabama. Ainsworth was elected as national chairman of the Aerospace States Association and is a member of the Alabama Workforce Council. He also heads the Lieutenant Governor’s Small Business Commission and the Lieutenant Governor’s Commission on a 21st Century Workforce. -

2020 Abstract of Votes Cast

2020 Abstract of Votes Cast Office of the Secretary of State State of Colorado Jena Griswold, Secretary of State Christopher P. Beall, Deputy Secretary of State Judd Choate, Director of Elections Elections Division Office of the Secretary of State 1700 Broadway, Suite 550 Denver, CO 80290 Phone: (303) 894-2200, ext. 6307 Official Publication of the Abstract of Votes Cast for the Following Elections: 2019 Odd-Year 2020 Presidential Primary 2020 Primary 2020 General Dear Coloradans, It is my privilege to present the biennial election abstract report, which contains the official statewide election results for the 2019 coordinated election, 2020 presidential primary, 2020 statewide primary, and 2020 general election. This report also includes voter turnout statistics and a directory of state and county elected officials. The Colorado Secretary of State’s Election Division staff compiled this information from materials submitted by Colorado’s 64 county clerk and recorders. Additional information is available at Accountability in Colorado Elections (ACE), available online at https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/ACE/index.html. Without a doubt, the 2020 election year will be remembered as one of our state’s most unusual and most historic. After starting with the state’s first presidential primary in 20 years, we oversaw two major statewide elections amidst a global pandemic and the worst forest fires in Colorado’s history. Yet, despite those challenges, Colorado voters enthusiastically made their voices heard. We set state participation records in each of those three elections, with 3,291,661 ballots cast in the general election, the most for any election in Colorado history. -

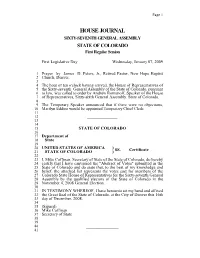

HOUSE JOURNAL SIXTY-SEVENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY STATE of COLORADO First Regular Session

Page 1 HOUSE JOURNAL SIXTY-SEVENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY STATE OF COLORADO First Regular Session First Legislative Day Wednesday, January 07, 2009 1 Prayer by James D. Peters, Jr., Retired Pastor, New Hope Baptist 2 Church, Denver. 3 4 The hour of ten o'clock having arrived, the House of Representatives of 5 the Sixty-seventh General Assembly of the State of Colorado, pursuant 6 to law, was called to order by Andrew Romanoff, Speaker of the House 7 of Representatives, Sixty-sixth General Assembly, State of Colorado. 8 9 The Temporary Speaker announced that if there were no objections, 10 Marilyn Eddins would be appointed Temporary Chief Clerk. 11 12 ______________ 13 14 15 STATE OF COLORADO 16 17 Department of 18 State 19 20 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) 21 STATE OF COLORADO ) SS. Certificate 22 23 I, Mike Coffman, Secretary of State of the State of Colorado, do hereby 24 certify that I have canvassed the "Abstract of Votes" submitted in the 25 State of Colorado and do state that, to the best of my knowledge and 26 belief, the attached list represents the votes cast for members of the 27 Colorado State House of Representatives for the Sixty-seventh General 28 Assembly by the qualified electors of the State of Colorado in the 29 November 4, 2008 General Election. 30 31 IN TESTIMONY WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand and affixed 32 the Great Seal of the State of Colorado, at the City of Denver this 16th 33 day of December, 2008. 34 35 (Signed) 36 Mike Coffman 37 Secretary of State 38 39 40 _______________ 41 Page 2 House Journal--1st Day--January 07, 2009 1 November 4, 2008 General Election Final Results 2 3 Candidate Vote Totals Percentage 4 5 St. -

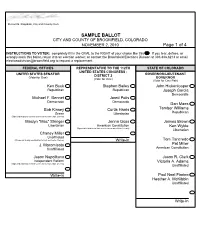

Test Ballot Print Document

Russell G. Ragsdale, City and County Clerk SAMPLE BALLOT CITY AND COUNTY OF BROOMFIELD, COLORADO NOVEMBER 2, 2010 Page 1 of 4 INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTER: completely fill in the OVAL to the RIGHT of your choice like this If you tear, deface, or wrongly mark this ballot, return it to an election worker; or contact the Broomfield Elections Division at 303.438.6213 or email [email protected] to request a replacement. FEDERAL OFFICES REPRESENTATIVE TO THE 112TH STATE OF COLORADO UNITED STATES CONGRESS - GOVERNOR/LIEUTENANT UNITED STATES SENATOR DISTRICT 2 (Vote for One) GOVERNOR (Vote for One) (Vote for One Pair) Ken Buck Stephen Bailey John Hickenlooper Republican Republican Joseph Garcia Democratic Michael F. Bennet Jared Polis Democratic Democratic Dan Maes Bob Kinsey Curtis Harris Tambor Williams Green Libertarian Republican (Signed delcaration to limit service to no more than 2 terms) Maclyn "Mac" Stringer Jenna Goss Jaimes Brown Libertarian American Constitution Ken Wyble (Signed declaration to limit service to no more than 3 terms) Libertarian Charley Miller Unaffiliated (Chose not to sign declaration to limit service to 2 terms) Write-in Tom Tancredo J. Moromisato Pat Miller Unaffilliated American Constitution Jason Napolitano Jason R. Clark Independent Reform Victoria A. Adams (Signed declaration to limit service to no more than 2 terms) Unaffiliated Write-in Paul Noel Fiorino Heather A. McKibbin Unaffiliated Write-in Page 2 of 4 SECRETARY OF STATE STATE REPRESENTATIVE - Shall Judge Katherine R. Delgado of (Vote for One) DISTRICT 33 the 17th Judicial District be retained in (Vote for One) office? Scott Gessler Donald Beezley YES NO Republican Republican Shall Judge Thomas R. -

Elected Officials Contact List

2020 ELECTED OFFICIALS TERMS NAME BUSINESS ADDRESS FIRST MOST RECENT TERM(S) IN OFFICE AFFILIATION BUSINESS PHONE / FAX ELECTED ELECTION OFFICE E-MAIL OR WEB SITE JOSEPH R. BIDEN UNITED STATES 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW PRESIDENT Washington DC 20500 Democrat 2020 2020 1st Term of Office-4 years Term Limit-Two 202.456.1414 www.whitehouse.gov/contact KAMALA D. HARRIS UNITED STATES 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW VICE-PRESIDENT Washington DC 20500 Democrat 2020 2020 1st Term of Office-4 years Term Limit-None 202.456.1414 www.whitehouse.gov/contact JOHN HICKENLOOPER UNITED STATES Senate Office Building Suite SR-B85 SENATOR Democrat 2020 2020 1st Term of Office-6 years Washington DC 20510 Term Limit-None 202.224.5941 www.hickenlooper.senate.gov MICHAEL F. BENNET UNITED STATES Senate Office Building 261 Russell 2009 SENATOR Democrat 2016 2nd Term of Office-6 years Washington DC 20510 (appointed) Term Limit-None 202.224.5852 www.bennet.senate.gov JOE NEGUSE 1419 Longworth House Office Building UNITED STATES CONGRESSIONAL Washington DC 20515 DISTRICT 2 1220 S College Ave Unit 100A Democrat 2018 2020 2nd Term of Office-2 years Fort Collins CO 80524 Term Limit-None 202.225.2161 https://neguse.house.gov JARED POLIS COLORADO STATE State Capitol Building 200 E Colfax Ave Ste 136 GOVERNOR Democrat 2018 2018 1st Term of Office-4 years Denver CO 80203-1792 Term Limit-Two consecutive 303.866.2471 fax 303.866.2003 www.colorado.gov/governor DIANNE PRIMAVERA COLORADO STATE State Capitol Building 200 E Colfax Ave Ste 130 LT. GOVERNOR Democrat 2018 2018 1st Term of -

DEMOCRATS EMERGE UNITED from FIRST-EVER LIEUTENANT GOVERNORS MEETING DLGA Meets for the First-Time Since Establishing Itself As National Organization

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE November 27, 2018 DEMOCRATS EMERGE UNITED FROM FIRST-EVER LIEUTENANT GOVERNORS MEETING DLGA meets for the first-time since establishing itself as national organization ALEXANDRIA, VA — Members of the Democratic Lieutenant Governors Association emerged united on innovative solutions to help grow their states’ economies, strengthen the middle class, and help gain access to quality healthcare and education after their first-ever meeting in Alexandria today all while doubling down on efforts to help get more Democrats elected to office. “Progress at the state level is more important now than ever and with my fellow DLGA members, we’re working to develop and advance an agenda that improves the lives of all Americans,” said Lt. Governor and DLGA Chairman Justin Fairfax. “Lt. Governors are, for the first time, united on solutions to grow the economy and strengthen the middle class and working together to do more at the state level. Our new members are already upcoming leaders in their states and future national leaders. DLGA will continue to recruit and encourage more quality candidates to run for the second-in-command position in their states.” The DLGA grew its ranks by more than 50% in the 2018 mid-term elections, going from 14 to 23, with record diversity among the incoming class of Democratic Lt. Governors. Democrats flipped 9 GOP-held lieutenant governorships, defended 5 open seats, and re-elected 3 incumbents. With these wins, Democratic Lieutenant Governors now lead - and look like - the majority of the American population. “As Democrats, there is nothing more important we can do than to begin rebuilding at the state level,” said Delaware Lt.