Reducing the Risk of Injury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heavy Equipment Technology Required Tool List

Heavy Equipment Technology Required Tool List WRENCHES 1 1/2” Drive socket set: - Sockets, 3/8” to 1-1/14”, 6 point, shallow well - Sockets, 7/16” to 1-1/8”, 6 point, deep well - Sockets, 7/16” to 15/16”, Impact, 6 point, shallow well - Sockets, 7/16” to 15/16”, Impact, 6 point, deep well - Sockets, 10mm to 32 mm, 6 point, shallow well - Sockets, 10mm to 19mm, 6 point, deep well - Sockets, 10mm to 25mm’ Impact, 6 point, deep well - Ratchet - Breaker Bar - Drive Extensions: 1-1/2”, 3”, 5”, 10”, and 15” - Drive Adapter: 1/2” to 3/8” - 250 lb. Torque Wrench, Micrometer adjust - Impact Wrench, 3/4 or 1/2, Pneumatic or Battery - Universal Joint 1 3/8” Drive socket set: - Sockets, 1/4" to 15/16”, 6 point, shallow well - Sockets, 6mm to 19mm, 6 point shallow well - Universal Sockets, 3/8” to 3/4", 6 point shallow well - Sockets, T30 to T55, Drivers - Spark plug Sockets, 5/8” and 13/16” - Ratchet - Breaker bar - Drive extensions: 1-1/2”, 3”, 6”,10” - Universal Joint 1 1/4” Drive socket set: - Sockets, 3/16” to 9/16”, 6 point, shallow well - Sockets, 3/16” to 9/16”, 6 point, deep well - Sockets, 5.5mm to 14mm, 6 point, shallow well - Sockets, 5.5mm to 14mm, 6 point, deep well - Sockets, T8 to T27, Drivers - Ratchet - Drive extensions: 2”, 4”, 6” - Universal Joint 1 Combination End set: - 1/4" to 1-1/4”, Long - 6mm to 24mm, Long 1 Flare Nut set: - 1/4" to 13/16” - 9mm to 21mm 1 Ratcheting Box End: - 1/4” x 3/8” and 3/16” x 5/16”, Square, Air Conditioning 1 8” Adjustable Wrench 1 14” Pipe Wrench 1 Hex Key set: - 5/64” to 3/8”, Long Arm -1.5mm to -

EYELET PLIERS Instruction Guide for Eyelets

574 EYELET PLIERS Instruction Guide for Eyelets Instrucciones españolas ©2015 Prym Consumer USA Inc. 950 Brisack Rd. • Spartanburg, SC 29303 www.dritz.com 574 EYELET PLIERS – Instructions Fabric Preparation for Use two layers of light to medium-weight fabric, reinforced with interfacing. " and ¼" Eyelets Mark position of eyelets. ⁵∕₃₂ Test an eyelet on swatch of fabric. Instructions for Cutting ⁵∕₃₂" Holes in Fabric Pliers Tools: Inserting Tools: Insert die base (large hole opening Metal Die Metal Cone facing out) in one side of pliers Base Punch and cone punch in other side. Cutting Holes: Removing Tools: 1. Position fabric in pliers and 2. After cutting several holes, it may be 3. If pliers’ tools will not cut Slip hook of gray tool remover center tools over mark. necessary to clear hole cutouts from through your specic type of inside ledge of pliers and press Squeeze pliers rmly to die base. Use a strong straight pin to fabric, trace inside of eyelet down to release tool. cut hole. remove fabric cutouts from die. and cut hole with scissors. Repeat for opposite side. 1. 2. 3. Instructions for Cutting ¼" Holes in Fabric Pliers Tools: Inserting Tools: Insert round die base in one Metal Round Metal Cone side of pliers and cone punch Die Base Punch in other side. Cutting Holes: Removing Tools: 1. Position fabric in pliers and 2. After cutting several holes, it may be 3. If pliers’ tools will not cut Slip hook of gray tool remover center tools over mark. necessary to clear hole cutouts from through your specic type of inside ledge of pliers and press Squeeze pliers rmly to die base. -

Tool Management

TOOL MANAGEMENT www.haimer-usa.com HAIMER TOOL MANAGEMENT LOGISTICS SYSTEM – OVERVIEW Corner module with perforated wall Connection part shrink fit machine Power Clamp Premium Plus Connection part measuring and balancing system Tool Dynamic Preset Waste disposal module Shelf module folders Assembly station Vertical cabinet universal Tool holder rack 2 Workbench assembly module Corner module with rear wall for storing collets and tools Workbench info module Shelf module parts Magazine cabinet Vertical cabinet tool holders 3 TOOL MANAGEMENT – FOR EFFICIENT WORKING Use: The HAIMER Tool Management completes the HAIMER product program as a sys- tem partner around tool clamping. That means HAIMER offers the complete Tool Management equipment from a single source. As a complete solution for tool pre- setting and tool management, the HAIMER Tool Management provides you with functional and ergonomic criteria for the design of work stations. The storage, setup and management of tools is simplified and optimized by the HAIMER solutions so that efficient working is guaranteed. – Modular room design according to the customer's requirements – Shrinking, balancing and presetting already integrated into the concept – Tidy and isolated solution for concentrated working 4 Technical data subject to change without prior notice CORNER MODULE Corner module with perforated wall Use: The perforated back wall and drawer unit provide a clean and structured workspace. The three integrated LED spots ensure a continually bright and comfortable working atmosphere. Delivery includes: – Corner module with a perforated wall, roof with LED lighting, drawer unit Description Order No. Corner module 4.0 84.802.00.3 Technical data subject to change without prior notice 5 WORKBENCH ASSEMBLY MODULE Picture shows: Assembly module with special configuration, Order No. -

1. Hand Tools 3. Related Tools 4. Chisels 5. Hammer 6. Saw Terminology 7. Pliers Introduction

1 1. Hand Tools 2. Types 2.1 Hand tools 2.2 Hammer Drill 2.3 Rotary hammer drill 2.4 Cordless drills 2.5 Drill press 2.6 Geared head drill 2.7 Radial arm drill 2.8 Mill drill 3. Related tools 4. Chisels 4.1. Types 4.1.1 Woodworking chisels 4.1.1.1 Lathe tools 4.2 Metalworking chisels 4.2.1 Cold chisel 4.2.2 Hardy chisel 4.3 Stone chisels 4.4 Masonry chisels 4.4.1 Joint chisel 5. Hammer 5.1 Basic design and variations 5.2 The physics of hammering 5.2.1 Hammer as a force amplifier 5.2.2 Effect of the head's mass 5.2.3 Effect of the handle 5.3 War hammers 5.4 Symbolic hammers 6. Saw terminology 6.1 Types of saws 6.1.1 Hand saws 6.1.2. Back saws 6.1.3 Mechanically powered saws 6.1.4. Circular blade saws 6.1.5. Reciprocating blade saws 6.1.6..Continuous band 6.2. Types of saw blades and the cuts they make 6.3. Materials used for saws 7. Pliers Introduction 7.1. Design 7.2.Common types 7.2.1 Gripping pliers (used to improve grip) 7.2 2.Cutting pliers (used to sever or pinch off) 2 7.2.3 Crimping pliers 7.2.4 Rotational pliers 8. Common wrenches / spanners 8.1 Other general wrenches / spanners 8.2. Spe cialized wrenches / spanners 8.3. Spanners in popular culture 9. Hacksaw, surface plate, surface gauge, , vee-block, files 10. -

How to Use Tools / Mistakes to Avoid CARLTSOE SAFETY TOOLS

CARLTSOE SAFETY TOOLS If you just had the right tools How to Use Tools / Mistakes to Avoid Tool Proper Uses Abuse/Misuse Nail Hammers Nail hammers are intended for driving and pulling common, Never strike one hanmmer with or against another hammer unhardened nails only, and for ripping apart wooden or a hatchet. Never strike nail pullers, steel chisels or structures. They may be used to strike nail sets with the other hardened objects with a nail hammer as the face may center of the striking face. chip, possibly resulting in eye or other serious injury. Ball Pein Hammers Ball pein hammers of the proper size are designed for striking chisels and punches, and for riveting, shaping and Strike squarely and avoid glancing blows that may cause straightening unhardened metal. the edge of the face to chip, possibly resulting in eye or When striking a struck tool (chisel or punch), the striking face other serious injury. Never strike with or against the side, of the hammer should have a diameter at least 3/8" larger or cheek, of any hammer. than the struck face of the tool. Riveting and Setting Hammers The Riveting hammer is designed for driving and spreading Never use these special-purpose hammers for general- rivets on sheet metal work. The Setting hammer is designed purpose work. The square, sharp edges of the setting for forming sharp corners, closing and peining seams and lock hammer make it vulnerable to chipping if improperly used. edges, and for use by glaziers for inserting glazier points. Never strike against other steel tools. -

Pliers, Clamping, & Cutting

PLIERS, CLAMPING, & CUTTING TABLE OF CONTENTS XL SERIES PLIERS . 742-743 LOCK JOINT PLIERS . .744 POWER-TRACK® II PLIERS . .745 ASSORTED PLIERS SETS . .746 NEEDLE-NOSE PLIERS . 747-748 CUTTING PLIERS . 749-752. LINEMAN'S PLIERS . 752-753. SPECIALTY PLIERS. 754 MINIATURE PLIERS . 755. LOCKING PLIERS . 756-762. LOCKING C-CLAMPS . 762-765 SAFETY WIRE TWISTERS. 766 WIRE STRIPPERS & CUTTERS . .767 AUTOMOTIVE PLIERS . 768-769. RETAINING RING PLIERS SETS . 770-772 RETAINING RING PLIERS . 773-774 1000V PLIERS . 775-781. HACKSAW . 782. C-CLAMPS . 782-784 EYE BOLTS . 785. SNIPS . 785-787 . MULTI-PURPOSE TOOLS . .787 KNIVES. 788 PROTO® STAINLESS STEEL ELECTRICIAN'S SCISSORS A handy electrician's tool that can accomplish common tasks like stripping, crimping, cutting, and snipping from thin delicate wires to thicker multi-core cables, conveniently locked on the belt until needed. Ergonomic handles with hole for tethering. Built-in wire stripper can strip and crimp for AWG 12, 14 and 16 cables. Stainless steel construction. Includes a holder with a quick release button and a belt clip. Cuts multi- wire cables and snips tiny wires. Micro anti-slip teeth on blades for better cutting grip. SAFETY WIRE PLIERS Safety wire is a type of positive locking device that prevents fasteners from loosening due to vibration and other forces. The presence of safety wiring also serves to indicate that the fasteners have been properly tightened. Safety wire is available in a variety of gauges and materials, depending on the application. In aircraft and racing applications, stainless steel wire is used, most commonly in .032" diameter. Typically, the wire is threaded through a hole drilled into a fastener or part, then twisted and anchored to a second fastener or part, then twisted again. -

Enghandbook.Pdf

785.392.3017 FAX 785.392.2845 Box 232, Exit 49 G.L. Huyett Expy Minneapolis, KS 67467 ENGINEERING HANDBOOK TECHNICAL INFORMATION STEELMAKING Basic descriptions of making carbon, alloy, stainless, and tool steel p. 4. METALS & ALLOYS Carbon grades, types, and numbering systems; glossary p. 13. Identification factors and composition standards p. 27. CHEMICAL CONTENT This document and the information contained herein is not Quenching, hardening, and other thermal modifications p. 30. HEAT TREATMENT a design standard, design guide or otherwise, but is here TESTING THE HARDNESS OF METALS Types and comparisons; glossary p. 34. solely for the convenience of our customers. For more Comparisons of ductility, stresses; glossary p.41. design assistance MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF METAL contact our plant or consult the Machinery G.L. Huyett’s distinct capabilities; glossary p. 53. Handbook, published MANUFACTURING PROCESSES by Industrial Press Inc., New York. COATING, PLATING & THE COLORING OF METALS Finishes p. 81. CONVERSION CHARTS Imperial and metric p. 84. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Steelmaking 4 Metals and Alloys 13 Designations for Chemical Content 27 Designations for Heat Treatment 30 Testing the Hardness of Metals 34 Mechanical Properties of Metal 41 Manufacturing Processes 53 Manufacturing Glossary 57 Conversion Coating, Plating, and the Coloring of Metals 81 Conversion Charts 84 Links and Related Sites 89 Index 90 Box 232 • Exit 49 G.L. Huyett Expressway • Minneapolis, Kansas 67467 785-392-3017 • Fax 785-392-2845 • [email protected] • www.huyett.com INTRODUCTION & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document was created based on research and experience of Huyett staff. Invaluable technical information, including statistical data contained in the tables, is from the 26th Edition Machinery Handbook, copyrighted and published in 2000 by Industrial Press, Inc. -

Hand and Power Tool Safety Tips Selecting the Right Tool, Posture and Positioning

UC Monthly Safety Spotlight, February 2012 Shop, Tool and Electrical Safety Hand and Power Tool Safety Tips Selecting the Right Tool, Posture and Positioning Understanding grips, force and pressure Power Grip: provides maximum hand power Pinch Grip: The hand grip provides control for high force tasks. All the fingers should for precision and accuracy. The tool is comfortably wrap around the tool handle gripped between the thumb and fingertips. Double-handle tools: plier-like tools measured Single hand grip: Tool is positioned to take by handle length and grip span. Grip span: The advantage of pressure from a hard surface, distance between the thumb and fingers when point or edge on any part of the body. the tool jaws are open or closed. Contact Pressure: Pressure from a hard surface, point, or edge on any part of your body. Awkward postures are postures that strain the neck, shoulders, elbows, wrists, hands or back. Bending, stooping, twisting and reaching are examples of awkward postures. Tool use and body positioning the work piece will affect your shoulder, elbow, wrist, hand or back posture. Choose an ergonomic tool requiring the least continuous force and which can be used without awkward postures. The right tool will help you to minimize pain and fatigue by keeping your neck, shoulders, and back relaxed and your arms at your sides. Avoid raising your shoulders and elbows; relaxed shoulders and elbows are more comfortable and will make it easier to drive downward. Ergonomic Tools • A tool becomes “ergonomic” only when it fits the task you are performing and it fits your hand without causing awkward postures, harmful contact pressures or other safety and health risks. -

Pliers Wrench Pliers and a Wrench in a Single Tool

86 06 250 Pliers Wrench pliers and a wrench in a single tool ● Replaces the need for sets of metric and imperial spanners ● Smooth jaws for damage free installation of plated fittings - working directly on chrome! ● Adjustable tightening tool ● Also excellent for gripping, holding, pressing and bending workpieces ● Push the button for adjustment on the workpiece ● Zero backlash jaw pressure prevents damage to edges of sensitive components ● Parallel jaws give a more solid grip; its design allows flexible adjustment of all widths up to the specified maximum size ● Reliable catching of the hinge bolt: no unintentional shifting ● The ratchet type principle allows quick and easy tightening and release of all bolted connections ● Lever transmission greater than 10 : 1 for strong gripping power ● Chrome vanadium electric steel, forged, oil-hardened ● With scaling for presetting the width apart from the workpiece The smooth jaws grip all parallel surfaces in the capacity range with a high degree of pressure if necessary and open up almost unlimited application possibilities for the pliers wrench: e.g. for tightening locknuts, exerting pressure to activate the adhesive power of contact adhesives, edge breaking in tile work, snapping cable ties, utilisation as a small vice. Article No. 86 06 250 EAN 4003773082408 Pliers chrome plated insulated with multi- Handles component grips, VDE- tested Insulation standard IEC 60900 DIN EN 60900 Pliers wrench: zero Conventional open end backlash contact wrench: edge pressure B2 mm 8,0 pressure, no damage to causes surface damage B3 mm 14,0 edges B1 mm 8,0 Adjustment positions 19 Capacities for nuts 2 Inch Capacities for nuts mm 52 Length mm 250 Net weight g 515 Fast adjustment at the Working on plated replaces the need for touch of a button fittings without damage sets of metric and of the surface imperial spanners technical change and errors excepted Ideal for bending operations KNIPEX-Werk C. -

PUNCHES and CHISELS Punches and Chisels the Anvil End on Heads of Snap-On® Punches and Chisels Are Machined to a Modified Parabolic Curve

PUNCHES AND CHISELS Punches and Chisels The anvil end on heads of Snap-on® punches and chisels are machined to a modified parabolic curve. This design directs the striking force to the center of the tool head to allow slow metal displacement. The parabolic curve controls mushrooming to reduce chipping and splitting. Heads should be re-dressed to their original shape with hand files as necessary. The tough steel alloy is machined and differentially heat treated for optimum performance. The hardness of the striking head is reduced to help toughness and add qualities that result in a slower mushrooming of the striking surface. PPC250BK Punch and Chisel Set. PPC100AK Punch and Chisel Set. ncludes 24 pcs. in KB2179 kit bag: Includes 10 pcs. in KB2175 kit bag: PPC1A PPC106A PPC205A PPC820B PPC812B PPC828B PPC15B PPC3A PPC108A PPC206A PPC824B PPC816B PPC12B PPC19B PPC250BK PPC4A PPC110A PPC208A PPC12B PPC820B PPC13B PPC103A PPC112 PPC210A PPC14B PPC824B PPC14B PPC104A PPC203A PPC812B PPC15B PPC100AK PPC105A PPC204A PPC816B PPC19B PPCD70BK Punch and Chisel Set. PPC210BK Punch and Chisel Set. Includes 7 pcs. in KB2183 kit bag: Includes 22 pcs. in KB2178 kit bag: PPC103A PPC106A PPC110A PPC1A PPC105A PPC204A PPC816B PPC104A PPC107A PPC5A PPC106A PPC205A PPC820B PPC105A PPC108A PPC3A PPC108A PPC206A PPC824B PPC210BK PPC4A PPC110A PPC208A PPC828B PPC103A PPC112 PPC210A PPCD70BK PPC104A PPC203A PPC812B PPCS60BK Punch and Chisel Set. Includes 6 pcs. in KB2185 kit bag: PPC715BK Punch and Chisel Set. PPC203A PPC205A PPC208A Includes 16 pcs. in KB2182 kit bag: PPC204A PPC206A PPC210A PPC1A PPC104A PPC203A PPC208A PPC3A PPC105A PPC204A PPC812B PPC4A PPC106A PPC205A PPC816B PPC715BK PPC103A PPC108A PPC206A PPC820B PPCS60BK PPC50AK Punch and Chisel Set. -

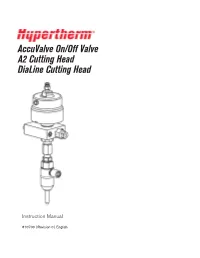

Accuvalve On/Off Valve A2 Cutting Head Dialine Cutting Head

AccuValve On/Off Valve A2 Cutting Head DiaLine Cutting Head Instruction Manual 810700 | Revision 0 | English AccuValve On/Off Valve, A2 Cutting Head, and DiaLine Cutting Head Instruction manual Revision 0 November 2013 Original instructions Hypertherm Waterjet 309 5th Ave NW New Brighton, MN 55112 +1 866-566- 7099 +1 651-294-8620 fax ⓒ 11/2013 Hypertherm Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document might be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system or translated into any language or any form by any means without the written permission of Hypertherm Inc. 2 Warranty Failure to follow and apply these instructions is considered to be misuse. Personal injury, product damage, or failure caused by misuse are not covered by the Hypertherm Inc. warranty. Hypertherm, Inc. warrants that its Products shall be free from defects in materials and workmanship, if Hypertherm is notified of a defect (i) with respect to the intensifier pumps within a period of two (2) years from the date of its delivery to you, and (ii) with respect to the cutting head assemblies within a period of one (1) year from its date of delivery to you, with the exception of Diamond orifices, which shall be within a period of six hundred (600) hours of use. General This warranty shall not apply to any Product which has been incorrectly installed, modified, or otherwise damaged. Hypertherm, at its sole option, shall repair, replace, or adjust, free of charge, any defective Products covered by this warranty which shall be returned with Hypertherm’s prior authorization (which shall not be unreasonably withheld), properly packed, to a Hypertherm facility, or to an authorized Hypertherm repair facility, all costs, insurance and freight prepaid. -

Cutting a Notch with a Bandsaw, Version 1.3

Cutting a Notch With a Bandsaw, Version 1.3 By R. G. Sparber Protected by Creative Commons.1 Every once in a while, I need to cut a square notch in a piece of stock. About half way through the task, I realize that a bit more planning would have been smart. Today I decided it was time to give this a bit more thought. It is easy to make cuts perpendicular to the edge. If the slot is narrow enough, repeated cuts will do the trick. I take a screwdriver and pry between cuts until the slivers break off. A bit of filing at the far end and I’m done. When making repeated cuts gets to be tedious, “successive approximation” works. I start by drilling a hole in each corner tangent to the layout lines. 1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. R. G. Sparber September 17, 2019 Page 1 of 7 Next, I make 3 cuts: two straight in and one diagonal. It is fairly easy to hit the tangent of the holes with the straight in cuts since I have layout lines defining the final notch. But sawing that diagonal by eye so it lands exactly in the corner is not easy. Given that the hole is there, it is also not necessary. Just head for that hole and avoid the layout lines.