Personal Networks on Social Network Sites (SNS) – Context and Personality Influences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diaspora Engagement Possibilities for Latvian Business Development

DIASPORA ENGAGEMENT POSSIBILITIES FOR LATVIAN BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT BY DALIA PETKEVIČIENĖ CONTENTS CHAPTER I. Diaspora Engagement Possibilities for Business Development .................. 3 1. Foreword .................................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction to Diaspora ............................................................................................ 5 2.1. What is Diaspora? ............................................................................................ 6 2.2. Types of Diaspora ............................................................................................. 8 3. Growing Trend of Governments Engaging Diaspora ............................................... 16 4. Research and Analysis of the Diaspora Potential .................................................... 18 4.1. Trade Promotion ............................................................................................ 19 4.2. Investment Promotion ................................................................................... 22 4.3. Entrepreneurship and Innovation .................................................................. 28 4.4. Knowledge and Skills Transfer ....................................................................... 35 4.5. Country Marketing & Tourism ....................................................................... 36 5. Case Study Analysis of Key Development Areas ...................................................... 44 CHAPTER II. -

Real-Time News Certification System on Sina Weibo

Real-Time News Certification System on Sina Weibo Xing Zhou1;2, Juan Cao1, Zhiwei Jin1;2,Fei Xie3,Yu Su3,Junqiang Zhang1;2,Dafeng Chu3, ,Xuehui Cao3 1Key Laboratory of Intelligent Information Processing of Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) Institute of Computing Technology, Beijing, China 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 3Xinhua News Agency, Beijing, China {zhouxing,caojuan,jinzhiwei,zhangjunqiang}@ict.ac.cn {xiefei,suyu,chudafeng,caoxuehui}@xinhua.org ABSTRACT There are many works has been done on rumor detec- In this paper, we propose a novel framework for real-time tion. Storyful[2] is the world's first social media news agency, news certification. Traditional methods detect rumors on which aims to discover breaking news and verify them at the message-level and analyze the credibility of one tweet. How- first time. Sina Weibo has an official service platform1 that ever, in most occasions, we only remember the keywords encourage users to report fake news and these news will be of an event and it's hard for us to completely describe an judged by official committee members. Undoubtedly, with- event in a tweet. Based on the keywords of an event, we out proper domain knowledge, people can hardly distinguish gather related microblogs through a distributed data acqui- between fake news and other messages. The huge amount sition system which solves the real-time processing need- of microblogs also make it impossible to identify rumors by s. Then, we build an ensemble model that combine user- humans. based, propagation-based and content-based model. The Recently, many researches has been devoted to automatic experiments show that our system can give a response at rumor detection on social media. -

Exploring the Relationship Between Online Discourse and Commitment in Twitter Professional Learning Communities

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bowling Green State University: ScholarWorks@BGSU Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Visual Communication and Technology Education Faculty Publications Visual Communication Technology 8-2018 Exploring the Relationship Between Online Discourse and Commitment in Twitter Professional Learning Communities Wanli Xing Fei Gao Bowling Green State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/vcte_pub Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Educational Technology Commons, and the Engineering Commons Repository Citation Xing, Wanli and Gao, Fei, "Exploring the Relationship Between Online Discourse and Commitment in Twitter Professional Learning Communities" (2018). Visual Communication and Technology Education Faculty Publications. 47. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/vcte_pub/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Visual Communication Technology at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Visual Communication and Technology Education Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Exploring the relationship between online discourse and commitment in Twitter professional learning communities Abstract Educators show great interest in participating in social-media communities, such as Twitter, to support their professional development and learning. The majority of the research into Twitter- based professional learning communities has investigated why educators choose to use Twitter for professional development and learning and what they actually do in these communities. However, few studies have examined why certain community members remain committed and others gradually drop out. To fill this gap in the research, this study investigated how some key features of online discourse influenced the continued participation of the members of a Twitter-based professional learning community. -

Developments in China's Military Force Projection and Expeditionary Capabilities

DEVELOPMENTS IN CHINA'S MILITARY FORCE PROJECTION AND EXPEDITIONARY CAPABILITIES HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2016 Printed for use of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: www.uscc.gov UNITED STATES-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION WASHINGTON: 2016 ii U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION HON. DENNIS C. SHEA, Chairman CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW, Vice Chairman Commissioners: PETER BROOKES HON. JAMES TALENT ROBIN CLEVELAND DR. KATHERINE C. TOB IN HON. BYRON L. DORGAN MICHAEL R. WESSEL JEFFREY L. FIEDLER DR. LARRY M. WORTZEL HON. CARTE P. GOODWIN MICHAEL R. DANIS, Executive Director The Commission was created on October 30, 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act for 2001 § 1238, Public Law No. 106-398, 114 STAT. 1654A-334 (2000) (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002 (2001), as amended by the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for 2002 § 645 (regarding employment status of staff) & § 648 (regarding changing annual report due date from March to June), Public Law No. 107-67, 115 STAT. 514 (Nov. 12, 2001); as amended by Division P of the “Consolidated Appropriations Resolution, 2003,” Pub L. No. 108-7 (Feb. 20, 2003) (regarding Commission name change, terms of Commissioners, and responsibilities of the Commission); as amended by Public Law No. 109- 108 (H.R. 2862) (Nov. 22, 2005) (regarding responsibilities of Commission and applicability of FACA); as amended by Division J of the “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008,” Public Law Nol. -

Public Displays of Connection

Public displays of connection J Donath and d boyd Participants in social network sites create self-descriptive profiles that include their links to other members, creating a visible network of connections — the ostensible purpose of these sites is to use this network to make friends, dates, and business connections. In this paper we explore the social implications of the public display of one’s social network. Why do people display their social connections in everyday life, and why do they do so in these networking sites? What do people learn about another’s identity through the signal of network display? How does this display facilitate connections, and how does it change the costs and benefits of making and brokering such connections compared to traditional means? The paper includes several design recommendations for future networking sites. 1. Introduction Since then, use of the Internet has greatly expanded and today ‘Orkut [1] is an on-line community that connects people it is much more likely that one’s friends and the people one through a network of trusted friends’ would like to befriend are present in cyberspace. People are accustomed to thinking of the on-line world as a social space. Today, networking sites are suddenly extremely popular. ‘Find the people you need through the people you trust’ — LinkedIn [2]. Social networks — our connections with other people — have many important functions. They are sources of emotional and ‘Access people you want to reach through people you financial support, and of information about jobs, other people, know and trust. Spoke Network helps you cultivate a and the world at large. -

Personal Networks and Urban Poverty: Preliminary Findings

brazilianpoliticalsciencereview ARTICLE Personal Networks and Urban Poverty: Preliminary Findings Eduardo Marques University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil Center for Metropolitan Studies / Brazilian Centre for Analysis and Planning (Cem/Cebrap), Brazil Renata Bichir, Encarnación Moya, Miranda Zoppi, Igor Pantoja and Thais Pavez Center for Metropolitan Studies / Brazilian Centre for Analysis and Planning (Cem/Cebrap), Brazil This article presents results of ongoing research into personal networks in São Paulo, exploring their relationships with poverty and urban segregation. We present the results of networks of 89 poor individuals who live in three different segregation situations in the city. The article starts by describing and analysing the main characteristics of personal networks of sociability, highlighting aspects such as their size, cohesion and diversity, among others. Further, we investigate the main determinants of these networks, especially their relationship with urban segregation, understood as separation between social groups in the city, and specific forms of sociability. Contrary to much of the literature, which takes into account only segregation of individual attributes in the urban space (race, ethnicity, socioeconomic level etc), this investigation tests the importance both of networks and of segregation in the reproduction of poverty situations. Keywords: Social networks; Urban poverty; Urban segregation; Sociability; São Paulo. Introduction ecently, a diverse set of studies have considered the importance of social networks to the Rsociability of individuals and to their access to a wide variety of tangible and intangible goods. In debates on poverty and inequality, relationship networks are frequently cited as key factors in obtaining work, in community and political organization, in religious behaviour and in sociability in general. -

Systematic Scoping Review on Social Media Monitoring Methods and Interventions Relating to Vaccine Hesitancy

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy www.ecdc.europa.eu ECDC TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy This report was commissioned by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and coordinated by Kate Olsson with the support of Judit Takács. The scoping review was performed by researchers from the Vaccine Confidence Project, at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (contract number ECD8894). Authors: Emilie Karafillakis, Clarissa Simas, Sam Martin, Sara Dada, Heidi Larson. Acknowledgements ECDC would like to acknowledge contributions to the project from the expert reviewers: Dan Arthus, University College London; Maged N Kamel Boulos, University of the Highlands and Islands, Sandra Alexiu, GP Association Bucharest and Franklin Apfel and Sabrina Cecconi, World Health Communication Associates. ECDC would also like to acknowledge ECDC colleagues who reviewed and contributed to the document: John Kinsman, Andrea Würz and Marybelle Stryk. Suggested citation: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy. Stockholm: ECDC; 2020. Stockholm, February 2020 ISBN 978-92-9498-452-4 doi: 10.2900/260624 Catalogue number TQ-04-20-076-EN-N © European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the -

Social Networks and Marketing

Social networks and marketing Carolin Kaiser Copyright GfK Verein Copying, reproduction, etc. – including of extracts – permissible only with the prior written con- sent of the GfK Verein. Responsible: Prof. Dr. Raimund Wildner Author: Carolin Kaiser GfK Verein Nordwestring 101, 90419 Nuremberg, Germany Tel.: +49 (0)911 395-2231 and 2368 – Fax: +49 (0)911 395-2715 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.gfk-verein.org Abstract Internet users are spending increasing amounts of time on social networking sites, cultivat- ing and expanding their online relationships. They are creating profiles, communicating and interacting with other network members. The information and opinion exchanges on social networking sites influence consumer decisions, making social networks an interesting plat- form for companies. By monitoring social networks, companies are able to gain knowledge about network members which is relevant for marketing purposes, so that by introducing the appropriate marketing measures, they can influence the market environment. The multiplici- ty and versatility of the information in tandem with the complexity of human behavior exhib- ited on social networks is posing new challenges for marketing. The present contribution illustrates how market research can assist marketing on social networks. In the first instance, it describes the potential benefits inherent in analyzing the information obtained from social networks, such as profiles, friendships and networking, for identifying and forecasting prod- uct preferences, advertising effectiveness, purchasing behavior and opinion dissemination. In the second instance, it discusses the opportunities and risks of marketing measures such as advertising, word-of-mouth marketing and direct marketing, on social networks. In each part, insights obtained from literature are summarized and research questions of relevance to consumer research are derived. -

Delay of Social Search on Small-World Graphs ⋆

⋆ Delay of Social Search on Small-world Graphs Hazer Inaltekin a,∗ Mung Chiang b H. Vincent Poor b aThe University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia bPrinceton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, United States Abstract This paper introduces an analytical framework for two small-world network models, and studies the delay of targeted social search by considering messages traveling between source and tar- get individuals in these networks. In particular, by considering graphs constructed on different network domains, such as rectangular, circular and spherical network domains, analytical solu- tions for the average social search delay and the delay distribution are obtained as a function of source-target separation, distribution of the number of long-range connections and geometri- cal properties of network domains. Derived analytical formulas are first verified by agent-based simulations, and then compared with empirical observations in small-world experiments. Our formulas indicate that individuals tend to communicate with one another only through their short-range contacts, and the average social search delay rises linearly, when the separation between the source and target is small. As this separation increases, long-range connections are more commonly used, and the average social search delay rapidly saturates to a constant value and stays almost the same for all large values of the separation. These results are qual- itatively consistent with experimental observations made by Travers and Milgram in 1969 as well as by others. Moreover, analytical distributions predicted by our models for the delay of social search are also compared with corresponding empirical distributions, and good statistical matches between them are observed. -

Diaspora Knowledge Flows in the Global Economy

E-Leader Budapest 2010 Diaspora Knowledge Flows in the Global Economy Dr. Martin Grossman Bridgewater State College Department of Management Bridgewater, MA, USA Abstract Globalization has fostered greater rates of mobility and an increasing reliance on transnational networks for commerce, social interaction, and the transfer of knowledge. This is particularly true among diaspora groups who have left their homelands in search of better economic and political environments. Unlike those of the past, today’s migrants stay connected via information and communications technology (ICT). Digital diaspora networks have the potential to reverse brain drain (the flight of human capital resulting from emigration) by facilitating knowledge sharing and technology transfer between the diaspora and the homeland. This paper explores the role that ICT-enabled diasporic networks are playing in reversing brain drain and stimulating brain gain and brain circulation. International development initiatives as well as empirical studies revolving around this concept are reviewed. The case of China is presented as an example of a country that has successfully leveraged its diaspora by implementing a number of strategies, including those based on ICT. A proposed research project, involving the Cape Verdean diaspora in Massachusetts, is also discussed. Introduction In today’s global economy intellectual capital has become the most important factor of production, underlying a nation’s ability to innovate and remain competitive (Stewart, 2007). Knowledge workers have become highly mobile, enabling them to seek out education and employment opportunities in other countries. While this might constitute a net gain for the country on the receiving end, it may also represent a serious loss of talent and ‘know-how’ from the home country. -

Popular Nationalist Discourse and China's Campaign to Internationalize the Renminbi

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2018 Great Powers Have Great Currencies: Popular Nationalist Discourse and China's Campaign to Internationalize the Renminbi Michael Stephen Bartee University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, International Economics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Bartee, Michael Stephen, "Great Powers Have Great Currencies: Popular Nationalist Discourse and China's Campaign to Internationalize the Renminbi" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1424. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1424 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. GREAT POWERS HAVE GREAT CURRENCIES: POPULAR NATIONALIST DISCOURSE AND CHINA’S CAMPAIGN TO INTERNATIONALIZE THE RENMINBI A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Josef Korbel School of International Studies University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Michael S. Bartee June 2018 Advisor: Suisheng Zhao © Copyright by Michael S. Bartee 2018 All Rights Reserved Author: Michael S. Bartee Title: GREAT POWERS HAVE GREAT CURRENCIES: POPULAR NATIONALIST DIS- COURSE AND CHINA’S CAMPAIGN TO INTERNATIONALIZE THE RENMINBI Advisor: Suisheng Zhao Degree Date: June 2018 ABSTRACT Why did the Chinese government begin promoting the internationalization of its cur- rency, the renminbi, after the 2008 global financial crisis? Only a few years earlier, Beijing balked at U.S. -

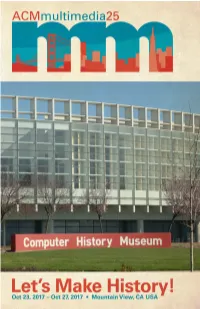

General Chairs' Welcome

General Chairs’ Welcome ACM Multimedia 2017 We warmheartedly welcome you to the 25th ACM Multimedia conference, which is hosted in the heart of Silicon Valley at the wonderful Computer History Museum in Mountain View, CA, USA. As you will notice, the second floor of the Computer History Museum is still nearly empty these days. 25 years later, the second floor will be filled with artifacts people have created today. Hopefully some of these artifacts are created by attendees of this conference. Let us work together and make history. We are celebrating our 25th anniversary with an extensive program consisting of technical sessions covering all aspects of the multimedia field in both form of oral and poster presentations, tutorials, panels, exhibits, demonstrations and workshops, bringing into focus the principal subjects of investigation, competitions of research teams on challenging problems, and an interactive art program stimulating artists and computer scientists to meet and discover together the frontiers of artistic communication. For our 25th ACM Multimedia conference, ACM Multimedia 2017, we unified for the first time the long and short papers into a single submission track and review process. In order to support the traditional short and long papers, the unified track has had a flexible range of paper lengths (6-8 pages plus references), which is not much longer than the previous short paper length (5 pages), while also supporting the traditional long papers with 8 pages plus references. This change was decided at the SIGMM Business Meeting at ACM Multimedia 2016 in Amsterdam. It aims at making the review process more consistent than the former short and long paper track.