Experience and Influence : Student and Parent Perspectives of an Alternative School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Official Boarding Prep School Directory Schools a to Z

2020-2021 DIRECTORY THE OFFICIAL BOARDING PREP SCHOOL DIRECTORY SCHOOLS A TO Z Albert College ON .................................................23 Fay School MA ......................................................... 12 Appleby College ON ..............................................23 Forest Ridge School WA ......................................... 21 Archbishop Riordan High School CA ..................... 4 Fork Union Military Academy VA ..........................20 Ashbury College ON ..............................................23 Fountain Valley School of Colorado CO ................ 6 Asheville School NC ................................................ 16 Foxcroft School VA ..................................................20 Asia Pacific International School HI ......................... 9 Garrison Forest School MD ................................... 10 The Athenian School CA .......................................... 4 George School PA ................................................... 17 Avon Old Farms School CT ...................................... 6 Georgetown Preparatory School MD ................... 10 Balmoral Hall School MB .......................................22 The Governor’s Academy MA ................................ 12 Bard Academy at Simon's Rock MA ...................... 11 Groton School MA ................................................... 12 Baylor School TN ..................................................... 18 The Gunnery CT ........................................................ 7 Bement School MA................................................. -

Liste Des Écoles Et Des Conseils Qui Utilisent Le Sgérn - 24 Juin 2021

Liste des écoles et des conseils qui utilisent le SGéRN - 24 juin 2021 Conseil École Algoma DSB ADSB Virtual Secondary School Algoma DSB Algoma Education Connection Algoma DSB Bawating Collegiate And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Central Algoma Secondary School Algoma DSB Central Algoma SS Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Chapleau High School Algoma DSB Elliot Lake Secondary School Algoma DSB Hornepayne High School Algoma DSB Korah Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Michipicoten High School Algoma DSB North Shore Adolescent Education School Algoma DSB North Shore Adult Education School Algoma DSB Sault Ste Marie Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Sir James Dunn C And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Superior Heights C and VS Algoma DSB W C Eaket Secondary School Algoma DSB White Pines Collegiate And Vocational School Avon Maitland DSB Avon Maitland District E-Learning Centre Avon Maitland DSB Avon Maitland DSB Summer School Avon Maitland DSB Bluewater SS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Central Huron Adult Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Central Huron Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Dublin School - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Exeter Ctr For Employment And Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB F E Madill Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Goderich District Collegiate Institute Avon Maitland DSB Listowel Adult Learning Centre NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Listowel District Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Milverton DHS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Mitchell Adult Learning Centre NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Mitchell District High School Avon Maitland -

View the This Year's Symposium Brochure

Global Ideas Institute Food Security: Child Malnutrition in India April 8, 2014 ASIAN INSTITUTE at THE MUNK SCHOOL of GLOBAL AFFAIRS “The Global Ideas Institute has allowed me to view the world from a radically different perspective and challenged me to participate in teamwork in an entirely new way to find solutions to the most pressing social issues facing the world today.” –Nicholas Elder, Upper Canada College Global Ideas Institute We live in one of the world’s most diverse cities, and we Th is year’s challenge focuses on child malnutrition in are experiencing a time of dramatic change. We see a more India. Addressing this issue is of critical importance. deeply interconnected world, fuelled by technology, with Working in teams and led by mentors from the University momentum enough to change corporations, media, and of Toronto and the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, governments in every country. At the same time, we see deep the students work in a distributed learning model to share divisions politically and economically, and an ailing planet. readings and conduct face-to-face discussions. In April, their Th e imperatives for a renewed sense of global citizenship and teams will identify and pitch their solutions to the challenge. global engagement are clear and unequivocal. We know that Th is symposium will take place at the Munk School of Global our best students in their fi nal years of high school are not Aff airs and will feature a panel of experts in the health and being off ered enough opportunities in the conventional development fi eld. -

List of Schools and Boards Using Etms - July 16, 2019

List of Schools and Boards Using eTMS - July 16, 2019 Board Name School Name Algoma DSB Bawating Collegiate And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Superior Heights C and VS Algoma DSB White Pines Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Sault Ste Marie Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Elliot Lake Secondary School Algoma DSB North Shore Adult Education School Algoma DSB Central Algoma SS Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Sir James Dunn C And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Central Algoma Secondary School Algoma DSB Korah Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Michipicoten High School Algoma DSB North Shore Adolescent Education School Algoma DSB W C Eaket Secondary School Algoma DSB Algoma Education Connection Algoma DSB Chapleau High School Algoma DSB Hornepayne High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB ALCDSB Summer School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre-Con Ed Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Nicholson Catholic College Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Theresa Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Paul Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Regiopolis/Notre-Dame Catholic High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Holy Cross Catholic Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Exeter Ctr For Employment And Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB South Huron District High School Avon Maitland DSB Stratford Ctr For Employment and Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Wingham Employment And Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Seaforth DHS Night School - CLOSED -

Federal School Code List, 2004-2005. INSTITUTION Office of Federal Student Aid (ED), Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME TITLE Federal School Code List, 2004-2005. INSTITUTION Office of Federal Student Aid (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 162p.; The Federal School Code List is published annually. It includes schools that are participating at the.time of printing. For the 2003-2004 Code list, see ED 470 328. AVAILABLE FROM Office of Federal Student Aid, U.S. Department of Education; 830 First Street, NE, Washington, DC 20202. Tel: 800-433-3243 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.studentaid.ed.gov. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MFOl/PCO7 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Coding; *College Applicants; *Colleges; Higher Education; *Student Financial Aid IDENTIFIERS *Higher Education Act Title IV This list contains the unique codes assigned by the U.S. Department of Education to all postsecondary schools participating in Title IV student aid programs. The list is organized by state and alphabetically by school within each state. Students use these codes to apply for financial aid on Free Application for Federal Student Aid (EAFSA) forms or on the Web, entering the name of the school and its Federal Code for schools that should receive their information. The list includes schools in the United States and selected foreign schools. (SLD) I Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. FSA FEDERAL STUDENT AID SlJh4MARY: The Federal School Code List of Participating Schools for the 2004-2005 Award Year. Dear Partner, We are pleased to provide the 2004-2005 Federal School Code List. This list contains the unique codes assigned by the Department of Education to schools participating in the Title N student aid programs. -

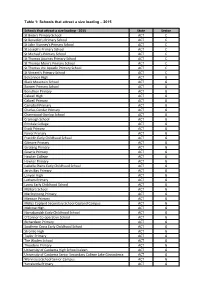

Table 1: Schools That Attract a Size Loading – 2015 Schools That Attract

Table 1: Schools that attract a size loading – 2015 Schools that attract a size loading - 2015 State Sector St Bede's Primary School ACT C St Benedict's Primary School ACT C St John Vianney's Primary School ACT C St Joseph's Primary School ACT C St Michael's Primary School ACT C St Thomas Aquinas Primary School ACT C St Thomas More's Primary School ACT C St Thomas the Apostle Primary School ACT C St Vincent's Primary School ACT C Belconnen High ACT G Black Mountain School ACT G Bonner Primary School ACT G Bonython Primary ACT G Calwell High ACT G Calwell Primary ACT G Campbell Primary ACT G Charles Conder Primary ACT G Charnwood-Dunlop School ACT G Cranleigh School ACT G Erindale College ACT G Evatt Primary ACT G Farrer Primary ACT G Franklin Early Childhood School ACT G Gilmore Primary ACT G Giralang Primary ACT G Gowrie Primary ACT G Hawker College ACT G Hawker Primary ACT G Isabella Plains Early Childhood School ACT G Jervis Bay Primary ACT G Lanyon High ACT G Latham Primary ACT G Lyons Early Childhood School ACT G Malkara School ACT G Maribyrnong Primary ACT G Mawson Primary ACT G Melba Copland Secondary School Copland Campus ACT G Melrose High ACT G Narrabundah Early Childhood School ACT G O'Connor Co-operative School ACT G Richardson Primary ACT G Southern Cross Early Childhood School ACT G Stromlo High ACT G Taylor Primary ACT G The Woden School ACT G Theodore Primary ACT G University of Canberra High School Kaleen ACT G University of Canberra Senior Secondary College Lake Ginninderra ACT G Wanniassa School Senior Campus ACT G Yarralumla -

Grades 4, 5, and Algebra OFFICIAL Results from the 2016-2017 School Year

2016-2017 CONTEST SCORE REPORT SUMMARY FOR GRADES 4, 5, AND ALGEBRA Summary of Results 4th Grade Contest Top 88 Schools out of 705 schools in 4th Grade Contest Rank School Town Team Score 1 Medina Elementary School Medina , WA 146 2 Argonaut Elementary School Saratoga , CA 142 3 Village Elementary School Skillman , NJ 139 4 Big Apple Academy Brooklyn , NY 137 5 Skinner North Classical Sch Chicago , IL 135 6 Greenbriar West ES Fairfax , VA 134 6 New Exploration into Science Tech & Math New York , NY 134 8 Churchville Elementary School Churchville , PA 129 8 Fulton Science Acad Private Sch Alpharetta , GA 129 8 Happy Hollow School West Lafayette , IN 129 11 Fern Hill School Oakville , ON 128 12 Nur-Ul-Islam Academy Cooper City , FL 126 12 P. S. 144Q-Sch. of Arts & Tech. Forest Hills , NY 126 14 Ardent Academy for Gifted Youth Irvine , CA 124 14 Dilworth ES San Jose , CA 124 14 NYC Laboratory School--PS 77 New York , NY 124 14 Ted Mersin College Mersin , TU 124 18 Charles Howitt Pub. School Richmond Hill , ON 123 18 Shanghai HS International Div. Shanghai , CI 123 20 Chadbourne ES Fremont , CA 121 20 William Berczy Public School Unionville , ON 121 22 Goodnoe Elementary School Newtown , PA 120 22 World Academy Nashua , NH 120 24 The Mirman School Los Angeles , CA 119 25 Academy for Gifted Children Richmond Hill , ON 118 25 American Heritage School Plantation , FL 118 25 Packanack School Wayne , NJ 118 28 Alcott Elementary School Redmond , WA 117 28 East Woods Elementary School Hudson , OH 117 28 Metrolina Regional Scholars Academy Charlotte , NC 117 28 Roosevelt School River Edge , NJ 117 28 Village School Pacific Palisades , CA 117 33 Garnet Valley Elem. -

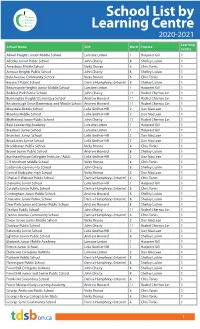

School List by Learning Centre 2020-2021

School List by Learning Centre 2020-2021 Learning School Name SOE Ward Trustee Centre Albion Heights Junior Middle School Lorraine Linton 1 Harpreet Gill 1 Allenby Junior Public School John Chasty 8 Shelley Laskin 1 Amesbury Middle School Vicky Branco 6 Chris Tonks 1 Armour Heights Public School John Chasty 8 Shelley Laskin 1 Bala Avenue Community School Vicky Branco 6 Chris Tonks 1 Baycrest Public School Denise Humphreys (Interim) 8 Shelley Laskin 1 Beaumonde Heights Junior Middle School Lorraine Linton 1 Harpreet Gill 1 Bedford Park Public School John Chasty 11 Rachel Chernos Lin 1 Bennington Heights Elementary School Andrew Howard 11 Rachel Chernos Lin 1 Bessborough Drive Elementary and Middle School Andrew Howard 11 Rachel Chernos Lin 1 Bloordale Middle School Leila Girdhar-Hill 2 Dan MacLean 1 Bloorlea Middle School Leila Girdhar-Hill 2 Dan MacLean 1 Blythwood Junior Public School John Chasty 11 Rachel Chernos Lin 1 Boys Leadership Academy Lorraine Linton 1 Harpreet Gill 1 Braeburn Junior School Lorraine Linton 1 Harpreet Gill 1 Briarcrest Junior School Leila Girdhar-Hill 2 Dan MacLean 1 Broadacres Junior School Leila Girdhar-Hill 2 Dan MacLean 1 Brookhaven Public School Vicky Branco 6 Chris Tonks 1 Brown Junior Public School Andrew Howard 8 Shelley Laskin 1 Burnhamthorpe Collegiate Institute / Adult Leila Girdhar-Hill 2 Dan MacLean 1 C R Marchant Middle School Vicky Branco 6 Chris Tonks 1 Cedarvale Community School John Chasty 8 Shelley Laskin 1 Central Etobicoke High School Vicky Branco 2 Dan MacLean 1 Charles E Webster Public -

130115 FOS School List.Xlsx

TDSB School List 2013 School Name Area Family of School Ward Adam Beck Junior Public School C ER11 Ward 16 Balmy Beach Community School C ER11 Ward 16 Beaches Alternative Junior School C ER11 Ward 16 Bowmore Road Junior and Senior Public School C ER11 Ward 16 Crescent Town Elementary School C ER11 Ward 16 D A Morrison Middle School C ER11 Ward 16 Duke of Connaught Junior and Senior Public School C ER11 Ward 16 Earl Beatty Junior and Senior Public School C ER11 Ward 16 Earl Haig Public School C ER11 Ward 16 East York Collegiate Institute C ER11 Ward 16 George Webster Elementary School C ER11 Ward 16 Gledhill Junior Public School C ER11 Ward 16 Glen Ames Senior Public School C ER11 Ward 16 Gordon A Brown Middle School C ER11 Ward 16 Kew Beach Junior Public School C ER11 Ward 16 Kimberley Junior Public School C ER11 Ward 16 Malvern Collegiate Institute C ER11 Ward 16 Norway Junior Public School C ER11 Ward 16 Parkside Elementary School C ER11 Ward 16 Presteign Heights Elementary School C ER11 Ward 16 Secord Elementary School C ER11 Ward 16 Selwyn Elementary School C ER11 Ward 16 Victoria Park Elementary School C ER11 Ward 16 William J McCordic School C ER11 Ward 16 Williamson Road Junior Public School C ER11 Ward 16 Birch Cliff Heights Public School C ER12 Ward 18 Birch Cliff Public School C ER12 Ward 18 Birchmount Park Collegiate Institute C ER12 Ward 18 Blantyre Public School C ER12 Ward 18 Buchanan Public School C ER12 Ward 19 Clairlea Public School C ER12 Ward 18 Cliffside Public School C ER12 Ward 18 Corvette Junior Public School C -

1 Name: Carlo Ricci Rank: Professor – Tenure Full-Time: Yes ACADEMIC

1 Name: Carlo Ricci Rank: Professor – Tenure Full-Time: Yes ACADEMIC DEGREES Designation Institution Department Year PhD University of Toronto (OISE) Curriculum: Social 2003 Toronto, Ontario Justice and Cultural Studies M.A.T. University of Toronto (OISE) Curriculum 2000 Toronto, Ontario BEd The University of Western Education 1997 Ontario London, Ontario BA Specialized York University Philosophy 1995 Honours Toronto, Ontario BA York University English/Psychology 1995 Ontario, Ontario EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Date Rank/Position Department Institution/Firm 2011 Professor MEd Nipissing University 2007- Associate Professor MEd Nipissing University 2011 2007 Part-time instructor MEd Brock University 2002- Assistant Professor Education Nipissing University 2007 2002 Part-time instructor Humanities University of Toronto 1998- Teacher English Peel District School Board 2002 1997 Teacher Elementary Supply Toronto District School Board HONOURS Academic, University and Professional Awards Year Honour/Award Received Awarding Agency or Institution 2 2002 $3800 University of Toronto (OISE) 252 Bloor St. West Toronto, Ontario Canada M5S 1V6 2001 $2800 University of Toronto (OISE) 252 Bloor St. West Toronto, Ontario Canada M5S 1V6 2000 $500 University of Toronto (OISE) 252 Bloor St. West Toronto, Ontario Canada M5S 1V6 Research Grants Year Value of Grant Granting Agency or Institution 2008 $25,000 SSHRC Strategic Research Grant (with Peter Trifonas and Mike McCabe) 2005 $5000 Nipissing University (with Dr. Peter Joong et. al) 2004 $3000 Nipissing University -

Oct. 2019 05 Vol

evergreen 05 VOL. OCT. 2019 05 VOL. Contents: OCT. 2019 1 Principal’s Message 2 Alumni News 3 Class Fund Update 4 Around Greenwood 6 Pursuing a Graduate Degree 8 Taking On New Challenges 10 School’s Out(side) 11 A Toast to Entrepreneurship 12 Pursuing Their Passions 14 Community Snapshots 16 Alumni Snapshots 18 Guess Who’s Back! 19 Staff Notes 20 Class Notes 22 Then & Now Evergreen is published annually by Greenwood College School. Editor: Kate Raven Writers: Kate Raven, Melissa St. Amant, Rex Taylor Photography: Margaret Mulligan Comments regarding Evergreen are always welcome. Feel free to contact us at: Advancement Department, Greenwood College School 443 Mt Pleasant Rd, Toronto, ON, M4S 2L8 or at [email protected] PRINCIPAL’S MESSAGE This past June, Greenwood’s Class of 2019 set off for new adventures. This leaving class ceremony was an important milestone not only for these 80 young people, but for our school: our alumni now number over 1,000 (1,004, to be exact). Our alumni are at several different stages in their lives, from our oldest grads in their late 20s and early 30s to our youngest alumni in their late teens. Some are just beginning their postsecondary journeys. Some are looking for that first full-time job in their chosen field. Some are in their early years in the workforce. Some are completing postgraduate degrees in fields including medicine, molecular genetics, psychology and music. Many have long-term partners and are starting families. There is no such thing as a “typical” Greenwood graduate – and for us, that means we’re achieving our goal of giving students the tools they need to pursue their passions. -

Torontonensis, 1963

R'H'eweT ;t Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Toronto http://archive.org/details/torontonensis65univ 1H 1965 ISpsis R HEWETT ^sisNbiSIS this is varsity Page 2 the back campus Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 soldiers tower Page 6 homecoming '64 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9 emmanuel college soldiers tower by night Page this first section of the yearbook has been published in advance to introduce torontonensis '65 to the students of the university. we wish to acknowledge our special thanks to mr. j. evans of the university alumni association for his assistance in helping us obtain most of the colour photographs used in this section. N ENS IS TORONTO contents torontonensis staff 15 photo essay "seven portraits" by sim posen 21 students administrative council 29 literary and art 37 hart house 68 sports 86 photo essay "fire escapes" by penny hewett activities 110 photo essay "windows" by a. a. jones 149 features 153 varsity 166 graduates 175 Page 13 'True patriotism does not ex- clude an understanding of the patriotism of others." Elizabeth II, Quebec, October, 1964. It is to this hope for a united Canada that we dedicate Torontonensis, J 965. British Information Service Page 14 torontonensis co-editors L. Hamilton N. J. Scott Page 15 torontonensis staff Gary Ross Kathy Watson Larry Thibideau Business Editor Activities Editor Graduates Editor Poge 16 torontonensis staff Wayne Shimada Clare Chu Jeannie Wyatt Photography Editor Literary and Art Graduates Page 1 7 torontonensis staff Gay Tugwell Ruth Essery Bill Rees Graduates Graduates Photography Poge 18 torontonensis staff Frank Tan PatMcDermott Krista Riko Features Activities Activities Page 19 torontonensis staff Kersti Wain Literary and Art Susan Corben Literary and Art Susan Lefebvre Features Janet Gusen Graduates Lorraine Dent Graduates Sim Posen Special Photography Pauline Nicholl Features Joanne Norwood Activities Sheila Ives Activities Penny Hewett Photography and Art Kit Doan Photography A.