The Archaeological Context of the Iwo Eleru Cranium from Nigeria and Preliminary Results of New Morphometric Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Africa Private Equity Confidence Survey More Capital Being Deployed

2016 Africa Private Equity Confidence Survey More capital being deployed – what about returns? Deloitte in Africa Our 353 partners and 4 864 professional staff serve clients across the African Continent ia is n Tu Morocco Algeria ra Libya a h Egypt a S rn e st We Cape Verde Islands Mauritania Mali Niger Sudan Senegal Chad Eritrea The Gambia Burkina Djibouti Faso Guinea-Bissau Guinea n Nigeria Somalia Beni Ethiopia Côte Central South ogo Sierra Leone d'Ivoire T Ghana African Sudan Republic Liberia Cameroon le il v Equatorial Guinea a Democratic z z Uganda Kenya ra Republic of the Gabon B - Congo o g Rwanda n o Burundi C Seychelles Cabinda Tanzania Comores Angola Zambia Malawi e qu bi m za r o a Zimbabwe M c Mauritius s a Namibia g a d Botswana a M Reunion Deloitte offices Swaziland South Africa Lesotho Countries serviced Countries not serviced 2 | 2016 Africa Private Equity Confidence Survey Foreword Deloitte is pleased to present to you the 2016 Africa Private Equity Confidence Survey (PECS). This forward looking survey provides growth in South Africa, its engine room, valuable insight into how fellow private offset somewhat by growth in Namibia and equity (PE) practitioners view the Mozambique. landscape at present as well as their future expectations. Unsurprisingly, respondents believe the fundraising environment will improve on African Private Equity (PE) markets have the back of more success stories out of grown exponentially in recent years and, sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), supported by an going by the results of the 2016 Africa increase in awareness of PE as an asset Private Equity Confidence Survey, this class with several large pension funds trend will continue, albeit at a slower opening up to its possibilities for the first pace. -

Africa from MIS 6-2: the Florescence of Modern Humans

Chapter 1 Africa from MIS 6-2: The Florescence of Modern Humans Brian A. Stewart and Sacha C. Jones Abstract Africa from Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) 6-2 saw Introduction the crystallization of long-term evolutionary processes that culminated in our species’ anatomical form, behavioral The last three decades represent a watershed in our under- florescence, and global dispersion. Over this *200 kyr standing of modern human origins. In the mid-1980s, evo- period, Africa experienced environmental changes on a lutionary genetics established that the most ancient human variety of spatiotemporal scales, from the long-term disap- lineages are African (Cann 1988; Vigilant et al. 1991). Since pearance of whole deserts and forests to much higher then, steady streams of genetic, paleontological and archae- frequency, localized shifts. The archaeological, fossil, and ological insights have converged into a torrent of evidence genetic records increasingly suggest that environmental that Africa is our species’ evolutionary home, both biological variability profoundly affected early human population sizes, and behavioral. When these changes occurred, however, densities, interconnectedness, and distribution across the remains less well understood, and much less so how and why. African landscape – that is, population dynamics. At the Where within Africa modern humans and our suite of same time, recent advances in anthropological theory predict behaviors developed is also problematic. One thing seems that such paleodemographic changes were central to struc- clear: the changes that shaped our species and its behavioral turing the very records we are attempting to comprehend. repertoire were gradual, rooted deeper in the Pleistocene than The book introduced by this chapter represents a first previously imagined. -

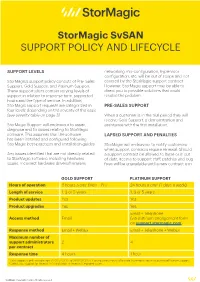

Stormagic Svsan SUPPORT POLICY and LIFECYCLE

StorMagic SvSAN SUPPORT POLICY AND LIFECYCLE SUPPORT LEVELS networking mis-configuration, hypervisor configuration, etc. will be out of scope and not StorMagic’s support policy consists of Pre- Sales covered by the StorMagic support contract. Support, Gold Support and Platinum Support. However, StorMagic support may be able to These support plans contain varying levels of direct you to possible solutions that could support in relation to response time, supported resolve the problem. hours and the type of service. In addition, StorMagic support requests are categorized in PRE-SALES SUPPORT four levels depending on the severity of the issue (see severity table on page 3) When a customer is in the trial period they will receive Gold Support, a demonstration and StorMagic Support will endeavour to assist, assistance with the first installation. diagnose and fix issues relating to StorMagic software. This assumes that the software LAPSED SUPPORT AND PENALTIES has been installed and configured following StorMagic best-practices and installation guides. StorMagic will endeavour to notify customers when support contracts require renewal. Should Any issues identified that are not directly related a support contract be allowed to lapse or is out to StorMagic software, including hardware of date, access to support staff, patches and bug issues, incorrect hardware drivers/firmware, fixes will be unavailable until a new contract is in GOLD SUPPORT PLATINUM SUPPORT Hours of operation 8 hours a day1 (Mon – Fri) 24 hours a day2 (7 days a week) Length of service 1, 3 or 5 years 1, 3 or 5 years Product updates Yes Yes Product upgrades Yes Yes Email + Telephone Access method Email (via platinum engagement form on support.stormagic.com) Response method Email + WebEx Email + Telephone + WebEx Maximum number of support administrators 2 4 per contract Response time 4 hours 1 hour 1 Gold Support is only available from 07:00 UTC/DST to 01:00 UTC/DST. -

An Annotated Fisheries Production Systems, Climate Change And

Fisheries Production Systems, Climate Change and Climate Variability in West Africa An Annotated Prepared for the GTZ/Worldfish Fisheries and Climate Change Project in West Africa Preface According to the United Nations’ definition, the West African region constitutes of 15 ECOWAS* member states plus Mauritania. It covers a total coastline of 6,500 km with a continental shelf of 310,050 km2 and extends over a surface area of 7,500,000 km2 with a population of nearly 250 million inhabitants. The countries of this region can be divided into coastal and landlocked states. The marine waters of almost all coastal countries are located in the Gulf of Guinea Large Marine Ecosys- tem, with periods of upwelling effects ensuring a high fisheries production. Peculiar differences for instance in fishing capacities, history of fishing, resource abundance and many others prevail within West African countries. The coastal countries belong- ing to the sub-regional fisheries commission (CSRP) are Cape Verde, The Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Senegal and Sierra Leone. These countries have exceptional climatic and ecological conditions and possess rich and abundant fisher- ies resources. A second group formed by Benin, Ghana, Nigeria, Togo, Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia is often referred to as ‘other coastal countries’. Finally, the landlocked countries comprise of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. They are practicing inland fish- eries and, compared to the coastal countries, have a low level of fish catch and also lower per capita fish consumption. Fisheries Production Systems, Climate Change and Climate Variability in West Africa: The West African fisheries sector is of high importance in terms of trade, food An Annotated Bibliography security and livelihoods; however, its magnitude varies greatly across countries. -

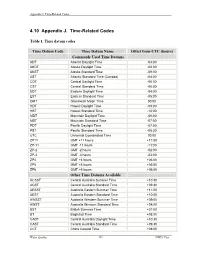

4.10 Appendix J. Time-Related Codes

Appendix J. Time-Related Codes 4.10 Appendix J. Time-Related Codes Table 1. Time datum codes Time Datum Code Time Datum Name Offset from UTC (hours) Commonly Used Time Datums ADT Atlantic Daylight Time -03:00 AKDT Alaska Daylight Time -08:00 AKST Alaska Standard Time -09:00 AST Atlantic Standard Time (Canada) -04:00 CDT Central Daylight Time -05:00 CST Central Standard Time -06:00 EDT Eastern Daylight Time -04:00 EST Eastern Standard Time -05:00 GMT Greenwich Mean Time 00:00 HDT Hawaii Daylight Time -09:00 HST Hawaii Standard Time -10:00 MDT Mountain Daylight Time -06:00 MST Mountain Standard Time -07:00 PDT Pacific Daylight Time -07:00 PST Pacific Standard Time -08:00 UTC Universal Coordinated Time 00:00 ZP11 GMT +11 hours +11:00 ZP-11 GMT -11 hours -11:00 ZP-2 GMT -2 hours -02:00 ZP-3 GMT -3 hours -03:00 ZP4 GMT +4 hours +04:00 ZP5 GMT +5 hours +05:00 ZP6 GMT +6 hours +06:00 Other Time Datums Available ACSST Central Australia Summer Time +10:30 ACST Central Australia Standard Time +09:30 AESST Australia Eastern Summer Time +11:00 AEST Australia Eastern Standard Time +10:00 AWSST Australia Western Summer Time +09:00 AWST Australia Western Standard Time +08:00 BST British Summer Time +01:00 BT Baghdad Time +03:00 CADT Central Australia Daylight Time +10:30 CAST Central Australia Standard Time +09:30 CCT China Coastal Time +08:00 Water Quality 336 NWIS User Appendix J. Time-Related Codes Table 1. -

Setup Config Wizard Values

Setup config wizard values <CountryName> <TimezoneId> <LicenseCountry> Timezone ID to be used Country ID to be used United States "-12:00 (International Date Line West)" 121 Afghanistan AF Canada "-11:00 (Midway Island, Samoa)" 120 Aland Islands AX Anguilla "-10:00 United States "- Hawaii"-Aleutian" 1 Albania AL Antigua and Barbuda "-10:00 United States "- Alaska"-Aleutian" 2 Algeria DZ Bahamas "-9:30 Alaskan Standard (Marquesas Islands)" 122 American Samoa AS Barbados "-9:00 United States "- Alaska Time" 3 Andorra AD Bermuda "-8:00 Canada (Vancouver, Whitehorse)" 4 Angola AO Cayman Islands "-8:00 Mexico (Tijuana, Mexicali)" 5 Anguilla AI Costa Rica "-8:00 United States "- Pacific Time" 6 Antarctica AQ Cuba "-7:00 Canada (Edmonton, Calgary)" 7 Antigua and Barbuda AG Dominica "-7:00 Mexico (Mazatlan, Chihuahua)" 8 Argentina AR Dominican Republic "-7:00 United States "- Mountain Time" 9 Armenia AM El Salvador "-7:00 United States "- MST no DST" 10 Aruba AW Greenland "-6:00 Canada "- Manitoba (Winnipeg)" 11 Australia AU Grenada "-6:00 Chile (Easter Islands)" 12 Austria AT Guam "-6:00 Mexico (Mexico City, Acapulco)" 13 Azerbaijan AZ Guatemala "-6:00 United States "- Central Time" 14 Bahamas BS Haiti "-5:00 United States "- Eastern Time" 0 Bahrain BH Honduras "-5:00 Bahamas (Nassau)" 15 Bangladesh BD Jamaica "-5:00 Canada (Montreal, Ottawa, Quebec)" 16 Barbados BB Mexico "-5:00 Cuba (Havana)" 17 Belarus BY Montserrat "-4:30 Venezuela (Caracas)" 18 Belgium BE Nicaragua "-4:00 Canada (Halifax, Saint John)" 19 Belize BZ Northern Mariana Islands "-4:00 Chile (Santiago)" 20 Benin BJ Panama "-4:00 Paraguay (Asunc cedilion)" 21 Bermuda BM Puerto Rico "-4:00 United Kingdom "- Bermuda (Bermuda)" 22 Bhutan BT St. -

Curriculum Vitae

El Hadji Samba Amadou DIALLO 6704 Chamberlain Ave. Saint Louis, MO 63130 (314) 604 5764 [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATION ÉCOLE DES HAUTES ÉTUDES EN SCIENCES SOCIALES, PARIS Doctorat de Troisième Cycle (PhD), Social Anthropology and History, July 2005 Dissertation: “The Transmission of Status and Power in the Senegalese Tijaniyya Islamic Brotherhood: the Case of the Sy Family of Tivaouane” or “La Transmission des statuts et des pouvoirs dans la Tijaniyya sénégalaise: le cas de la famille Sy de Tivaouane”. Advisors: Professor Marc Gaborieau (India and South East Asia Studies Center) and Dr. Constant Hamès (Center of Interdisciplinary Studies of Religion) Honors: Highest Honors with Congratulations of the Jury Diplôme d’Études Approfondies: Social Anthropology, October 1999 Honors: High Honors UNIVERSITÉ DE FRANCHE-COMTÉ, BESANÇON Master’s Degree: Sociology, September 1998 Honors: Honors Licence (B.A.): Sociology, September 1996 D.E.U.G.: (Diplôme d’études universitaires générales): Ethnology, Sociology, Philosophy, September 1995 TEACHING EXPERIENCE January 2011 – present Lecturer, African & African American Studies Program, Washington University in Saint Louis, Saint Louis, MO Teaching courses on Africa as well as an introductory and intermediate language course. Prepare weekly lectures, lead class discussions, and supervise undergraduate research projects. Independent work with graduate students in Comparative Literature, Religions Studies and Anthropology. Participate in departmental meetings. August 2006 - Adjunct -

Traditional Funeral and Burial Rituals and Ebola Outbreaks in West Africa: a Narrative Review of Causes and Strategy Interventions

Journal of Health and Social Sciences 2020; 5,1:073-090 The Italian Journal for Interdisciplinary Health and Social Development NARRATIVE REVIEW IN PUBLIC HEALTH AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES Traditional funeral and burial rituals and Ebola outbreaks in West Africa: A narrative review of causes and strategy interventions Chulwoo PARK1 Affiliations: 1 MSPH, Department of Global Health, The George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health. Corresponding author: Chulwoo Park, Department of Global Health, The George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health, 950 New Hampshire Ave NW, Suite 428N, Washington, D.C., United States 20052. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: In West Africa, traditional funerals and burials have proven main contributors to the spread of infectious diseases, such as Ebola, plague, the Marburg virus, and others. Although the World Health Organization has provided guidelines for the safe burial process after learning of the culture of the afterlife in Ebola-affected areas, little effort has been made to integrate theoretical interventions and models for changing West Africans’ funeral behavior. This research was conducted to study 1) the background of tradi- tional burial rituals, 2) interventions to contain Ebola outbreaks in West Africa, and 3) a strategic approach to future disease outbreak in the region. Methods: A narrative review was conducted by using four electronic databases—PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus—using search key terms and a manual search of Google Scholar and gray literature. A date range was open to all years, up to 2017 to include a historical aspect of Africans’ funerary rituals and 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. -

Abstracts of the 19Th Biennial Conference Of

NYAME AKUMA No. 70 DECEMBER 2008 0.2 Jan-Berend Stuut, Universität TH Bremen, Germany. Paleoclimate on ABSTRACTS OF THE 19 geological timescales: African climate BIENNIAL CONFERENCE OF since the Late Neogene. THE S OCIETY OF AFRICANIST In this presentation I will try to give a geolo- ARCHAEOLOGISTS, gist’s perspective on how past changes in e.g. tec- tonics, orbital forcing, and global climate change, FRANKFURT, GERMANY, shaped the African continent during the past 35 mil- SEPTEMBER 8-11, 2008 lion years. I will start with an overview of the present-day climate systems that act on the African continent 0. Plenary Session. Session Chair: and then go back into geological time to see what Diane Gifford-Gonzalez. these climate systems were like during geologic his- tory, and how these could have been important for 0.1 Nicholas Conard, Eberhard Karls the four large stages in human evolution and cultural history: Universität Tiibingen, Germany. Did behavioral modernity evolve exclusively •Hominid evolution between 6 and 2 Ma BP in Africa? •Appearance of modern man c. 100 Ka BP This paper provides an overview of patterns •Pleistocene/Holocene transition and the settling of cultural innovations in Africa, Eurasia and Aus- of the Sahara tralia. While Africa is certainly the source of anatomi- •Late Holocene aridification and the development cally modern humans, the archaeological record is of agriculture. less clear on matters concerning the paleogeography of cultural innovations. Several key innovations, par- ticularly in the areas of organic and symbolic arti- 0.3 David Killick, University of Arizona, facts, are documented outside of Africa prior to their USA. -

Download the Report 2016 Africa Private Equity Confidence Survey

2016 Africa Private Equity Confidence Survey More capital being deployed – what about returns? Deloitte in Africa Our 353 partners and 4 864 professional staff serve clients across the African Continent ia is n Tu Morocco Algeria ra Libya a h Egypt a S rn e st We Cape Verde Islands Mauritania Mali Niger Sudan Senegal Chad Eritrea The Gambia Burkina Djibouti Faso Guinea-Bissau Guinea n Nigeria Somalia Beni Ethiopia Côte Central South ogo Sierra Leone d'Ivoire T Ghana African Sudan Republic Liberia Cameroon le il v Equatorial Guinea a Democratic z z Uganda Kenya ra Republic of the Gabon B - Congo o g Rwanda n o Burundi C Seychelles Cabinda Tanzania Comores Angola Zambia Malawi e qu bi m za r o a Zimbabwe M c Mauritius s a Namibia g a d Botswana a M Reunion Deloitte offices Swaziland South Africa Lesotho Countries serviced Countries not serviced 2 | 2016 Africa Private Equity Confidence Survey Foreword Deloitte is pleased to present to you the 2016 Africa Private Equity Confidence Survey (PECS). This forward looking survey provides valuable insight into how fellow private equity (PE) practitioners view the landscape at present as well as their future expectations. African Private Equity (PE) markets have grown exponentially in recent years and, going by the results of the 2016 Africa Private Equity Confidence Survey, this trend will continue, albeit at a slower pace. An overwhelming majority of respondents across all three regions surveyed – Southern, East and West Africa – expect PE activity to increase in the next 12 months. Outside of South Africa, the region’s generally shallow capital markets and nascent stock exchanges mean PE remains a “natural” asset class for investors interested in Africa’s frontier and emerging markets. -

Your Guide to the Transit of Mercury of 11Th November 2019

1 Your guide to the Transit of Mercury of 11th November 2019 “The African Transit” Your guide to the Transit of Mercury 2019 2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons (Attribution - Non Commercial - ShareAlike) License. Please share/print/ photocopy/distribute this work widely, under this same license. This license is granted for non-commercial use only. For more information URL : https://www.africanastronomicalsociety.org/transit-of-mercury/ https://www.ska.ac.za/outreach/ https://www.saao.ac.za/outreach/ Email : [email protected] Facebook : skasouthafrica, saaonews, afas2.0 Twitter : ska_africa, saao Download from The pdf of this document is available for free download from the URL above Acknowledgements We thank all those who made images available online either under the Creative Commons License or by a copyleft through image credits. Adapted by Niruj Ramanujam (SARAO) from the Handbook on Transit of Mercury (2016), published by the Public Outreach and Education Committee of the Astronomical Society of India (ASI POEC) October 2019 Your guide to the Transit of Mercury 2019 3 1. Transit of Mercury DID YOU KNOW? The next transit Transit of Mercury, 9 May 2016, photographed by Elijah of Mercury that Mathews. The sharp dot left and below the centre is Mercury and the fuzzy spot higher up is a sunspot will be on 11 Nov 2032! The planets, with their moons, steadily revolve around the Sun, with Mercury taking 88 days and Neptune taking as The last transit much as 165 years to make one revolution. We barely of Mercury that notice any of this, unless something spectacular happens to was visible was on 9 May 2016. -

Thursday 26Th November 2020

The ‘This is not a webinar’ workshop series seeks to create space for sharing knowledge, experiences and learning with fellow campaigners. In addition to the global workshops focusing on youth, prisons and messaging – IDPC and AfricaNPUD are inviting our members and partners from Africa to attend a regional communications workshop to explore and discuss the language of policy reform. As stated in the title, this is not another webinar! It is designed as a space for a regionally-led discussion and exchange of ideas. The workshop will be held on Zoom, and will utilise group work, online tools,1 and – most crucially – the collective knowledge, expertise and insights of our network. This initial event will be held in English and French, with live translation provided. Thursday 26th November 2020 09:00 Cape Verde Time Zone 10:00 Greenwich Mean Time (inc some of West Africa) 11:00 West Africa Time Zone 12:00 South / Central Africa Time Zone 13:00 East Africa Time Zone 14:00 Mauritius / Seychelles / Reunion The access link will be sent individually to those who confirm their participation. This workshop will focus on how we communicate our messages around harm reduction, reform, decriminalisation and the rights of people who use drugs. Such communication is always hard. We need to reach out to a range of audiences, some of whom are outright hostile. We need to find language that people can understand, but which also captures a complex and highly-politicised topic. Instead of presentations, the workshop will use a series of case studies covering the range of communications platforms that we all use – social media, blogs, websites, media engagement, etc.