Risk Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia, US Sign Agreements to Boost Economic Development

facebook.com/ georgiatoday Issue no: 908/59 • DECEMBER 27 - 29, 2016 • PUBLISHED TWICE WEEKLY PRICE: GEL 2.50 In this week’s issue... Georgian Leaders Congratulate Local Jews on Hanukkah NEWS PAGE 5 Kleptocrats Attack Ukraine’s Reform-Minded Central Banker PAGE 6 Georgian Foreign Ministry Hosts Meeting on US-Georgia FOCUS Strategic Partnership ON SKI RESORTS An unprecedented example of Public-Private-Partnership is witnessed in the opening of the new Mitarbi Ski Resort PAGE 2 PAGE 7 Christmas Concert Culminates Georgia, US Sign Agreements to Boost Economic another Year of Successful Growth at Confl ict Divide Development PAGE 8 BY THEA MORRISON Welcome to Georgia Wine Campaign he United States Agency for Inter- Kicks Off for the national Development (USAID) is to allocate USD 22 million for Holiday Season Georgia’s economic development. Georgia’s Finance Minister, Dim- PAGE 9 Titry Kumsishvili, and Director of USAID’s Cau- casus Mission, Douglas Ball, signed three agree- ments to that effect on Thursday. Bryza: Russia Will Use the Changes were made to previously signed agree- ments increasing the amount of a pre-existing Defi nition of Terrorism to grant to the current USD 22 million fi gure. governance, and a “stable, integrated and healthy” tors, as well as more effectively managing nat- The Finance Ministry reports that the agree- society. ural resources and creating market-oriented Advance its Own Political ments cover a number of high-priority areas, The activities planned within the agreements jobs. Increasing the societal integration of per- Interests including inclusive and sustainable economic will be aimed at introducing business standards sons with disabilities and of IDPs has also been growth, democratic controls and accountable and increasing competitiveness in various sec- fi ngered as a focus. -

Israel Hits Back After UN Settlements Resolution

5 International Nieghbor News Israel Hits Back after China Welcomes Putin’s Comment on Bilateral Ties UN Settlements Resolution BEIJING - China on Mon- she said, adding that the JERUSALEM - Israel on the Prime Minister’s Of- day welcomed Russian two countries’ all-round Sunday summoned the fice and Foreign Ministry, President Vladimir Pu- cooperation not only envoys of countries that he said. tin’s comment on the two brings benefits to the two supported a UN resolu- Earlier on Sunday, Netan- countries’ relations at his countries and two peo- tion demanding an end yahu, who is also acting annual year-end press ples, but also contributes to the settlements, while foreign minister, instruct- conference. to world prosperity and suspending some interna- ed the foreign office to Russia and China have a stability. tional diplomatic ties and summon envoys of these relationship that is more “Strategic coordination coordination with the Pal- states for a reprimand than a simple strategic between China and Rus- estinians. meeting in Jerusalem. partnership, which will sia, which goes beyond Speaking at the cabinet’s Israeli Defense Minister be further promoted, Pu- bilateral level, serves as weekly meeting, Netan- Avigdor Lieberman in- tin said during his annual the ballast to safeguard- yahu told the ministers to structed the Israeli Coordi- press conference. ing world peace and sta- “minimize” meetings and nator of the Government’s “China highly appreci- bility,” she said. travels to the states that Activities in the Territories ates the positive attitude China stands ready to backed the resolution in to cease all meetings and in developing bilateral work with Russia to con- the UN Security Council talks with senior Palestin- ties by the Russian side,” tinue consolidating and on Friday, and with which ian officials, as another spokesperson Hua Chu- developing their compre- Israel has diplomatic rela- mean of rebuke. -

2018 August PFR GODOV OTCHET English.Indd

ANNUAL REPORT Pension Fund of the Russian Federation Contents Address by Russian Pension Fund Board Chairman 2 Events of the year 4 Digits of the year 6 About Russian Pension Fund 9 Management 10 Public services 16 Budget 26 Development of territorial infrastructure 30 Prevention of corruptive practices 33 Russian Pension Fund’s activity 35 Assignment and payment of pensions 36 Accumulation and repayment of pension savings 44 Account of pension and social security entitlements 52 State pension savings co-funding program 58 Maternity (family) capital program 60 Social benefi ts 62 Co-funding of social programs in Russian constituent territories 64 Awareness-raising activities 66 Appeal processing 71 International cooperation 73 Appendixes 77 Contacts of Russian Pension Fund divisions 78 Contacts of Russian Pension Fund 84 1 Annual Report 2017 Address by Russian Pension Fund Board Chairman The number of online requests for choosing Fund’s IT complex has an applied nature, Address by Russian or changing the pension delivery method above all. The task of modern technologies is increased 210% (vs. 3.8 million people in to raise the accessibility and quality of public 2017). The number of online applications for services in the fi eld of pensions and social Pension Fund maternity capital certifi cates grew 150% (to security. 788,000 persons). Board Chairman A no less important area of our activity is The implementation of new technologies information campaigns, which raise the level enabled the start of two major federal infor- of pension and social security awareness, mation projects developed and operated by foster knowledge of pension-forming mech- the Russian Pension Fund: the Unifi ed State anisms, and involve citizens in the accumu- Social-Security Information System (USSSIS) lation of their pensions. -

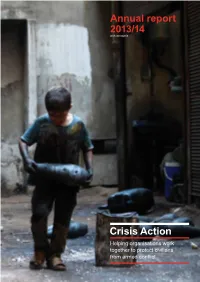

Annual Report 2013/14 with Accounts

Annual report 2013/14 with accounts Helping organisations work together to protect civilians from armed conflict We work for and with organisations and individuals across civil society who act to protect civilians from armed conflict. We are a catalyst and convenor of joint action, whose behind-the-scenes work enables coalitions to act quickly and effectively. As a coordinating body we seek no public profile or media spotlight; it is the voice of the coalition that matters. We are an international organisation whose only agenda is the protection of civilians. We are open about our objectives, welcoming scrutiny from anyone who wishes to understand who we are and what we do. Core partners Chair’s report 7 Action Contre la Faim (ACF) Center for Civilians in International Federation for Permanent Peace Conflict Human Rights (FIDH) Movement Aegis Trust Crisis Action’s team now comprises 33 full- Christian Aid International Medical Corps Refugees International Africa Peace Forum UK time staff located across eight small offices Concordis International Saferworld African Centre for Justice International Refugee Rights and Peace Studies (ACJPS) Cordaid Save the Children UK Initiative (IRRI) around the world. It is nothing short of African Research and Diakonia Save the Children US International Rescue Resources Forum (ARRF) Finn Church Aid Committee Stichting Vluchteling extraordinary that a team of this size, Agency for Cooperation on (Netherlands Refugee Global Centre for the Islamic Relief Worldwide Research in Development Foundation) Responsibility to Protect run on a budget of less than £2.5 million, (ACORD) Media in Cooperation and (GCR2P) Support to Life Transition (MICT) Amnesty International Human Rights Watch Tearfund is able to accomplish so much for so many vulnerable medica mondiale Arab Programme for Human (HRW) The Elders Rights Activists (APHRA) medico international civilians in so many conflicts. -

Donbass and the “Big Game”

Donbass and the “Big Game”: Reformatting Ukraine is on the Agenda. “Russia will not Remain on the Sidelines” By Oriental Review Region: Russia and FSU Global Research, June 04, 2015 In-depth Report: UKRAINE REPORT Oriental Review (Expert Journal, translated from Russian) Latest horrible ceasefire violations in Donbass by the Kiev’s regime are likely intended to demonstrate the “inefficiency” of the OSCE mission to its Western patrons and are evidence of Ukraine’s attempts to circumvent the jurisdiction of theMinsk truce co-brokered by Russia, Germany, and France. Indeed, Minsk-2 is very inconvenient for Poroshenko, because it documents for the first time the need for direct dialog between Kiev and the Donbass. And they need to discuss more than just war and peace, because in fact there are a whole range of issues that must be resolved politically, such as the format for local elections, as well as constitutional reform and economic recovery in Ukraine. Minsk-2 undermines the power structure in Ukraine, which after Maidan has been built around nationalist and military mobilization and the persecution of political opponents. There’s a good reason why President Poroshenko immediately tried to disavow the agreement as soon as he returned from Minsk. In March 2015 the Verkhovna Radapassed an amendment to the law on the special status of the districts controlled by Donetsk and Luhansk (in violation of the spirit of the Minsk agreement), rather than adopting a new law as Angela Merkel had asked Poroshenko to do. These actions, as well as others that undercut the foundations of the truce, are causing extreme irritation in Berlin and Paris. -

Social Change and the Russian Network Society Redefining Development Priorities in New Information Environments

FROM THE INTERNEWS CENTER FOR INNOVATION AND LEARNING Social Change and the Russian Network Society Redefining Development Priorities in New Information Environments Josh Machleder and Gregory Asmolov August 2011 ii | About the Authors Gregory Asmolov is a contributing editor to Runet Echo, a project of “Global Voices Online” that analyzes the Russian Internet. He has consulted on information technology, new media, and social media projects for The World Bank, American Councils for International Education, and In- ternews, and conducted research at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society. Asmolov has previously worked as a journalist for major Russian daily newspapers Kommersant and Novaya Gazeta, and served as news editor and analyst for Israeli TV. Asmolov is a co-founder of Help Map, the crowdsourcing platform, which was used to coordinate assistance to victims of wildfires in Russia in 2010 and won a Russian National Internet Award for best project in the “State and Society” category. Asmolov holds an MA in Global Communication from George Washington University and is working towards a PhD on New media, Innovation and Literacy at the London School of Economics. Josh Machleder is Internews’ Vice President for Europe and Eurasia Programs. He brings 12 years’ media development experience in the former Soviet Union and 10 years of Internews field management, in Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. He has worked for the Open Society Institute, IREX, and was an Alfa Fellow in Moscow in 2005 – 2006. Prior to working for Internews, Machleder worked in TV and Radio production in New York. Machleder holds BA and MA degrees from Columbia University. -

Health Care Crisis and Grassroots Social Initiative in Post-Soviet Russia

Review of European and Russian Affairs 6 (1), 2011 ISSN 1718-4835 HEALTH CARE CRISIS AND GRASSROOTS SOCIAL INITIATIVE IN POST-SOVIET RUSSIA Elena Maltseva University of Toronto Abstract This article analyzes the development of civil society in Russia in response to the fledging post-Soviet health care crisis. In recent years, Russian civil society has become significantly stronger and more actively engaged in public debates on social as well as political issues. This trend suggests that the process of social capital accumulation in Russia is well underway, thus instilling some hope for Russia’s future. To illustrate this recent trend, I will analyze the development of two grassroots movements in St. Petersburg, which help families of children diagnosed with cancer to overcome the everyday psychological, legal and financial difficulties associated with treatment, and to lobby the government to go forward with health care reform. This paper is based on the author's personal experience as a participant in one of the grassroots initiatives, published materials in Russian journals and newspapers and a series of interviews with volunteers. With this article, I hope to shed new light on developments in the Russian health care sector, and deepen our understanding of contemporary Russian civil society. © 2011 The Author(s) www.carleton.ca/rera 2 Review of European and Russian Affairs 6 (1), 2011 Introduction The collapse of communism generated much interest in the concept of civil society, defined by the Center for Civil Society at the London School of Economics as “the arena of un-coerced collective action around shared interests, purposes and values” (quot. -

Histoire De La Cuisine De Saint-Pétersbourg Pour La Vie

www.russiefrancophone.com № 1 (34) Janvier 2017 La Russie francophone Actualités • Culture • Économie • Histoire • Cinéma Faut-il parler à la Russie ? pages 6-7 © commons.wikimedia.org LA VIE EN RUSSIE LA VIE EN RUSSIE Suivez l’actualité de La Russie francophone sur Pour la vie, Histoire de www.russiefrancophone.com contre la guerre : la cuisine de Elizaveta Glinka Saint-Pétersbourg pages 8-9 pages 10-11 Janvier 2017 Janvier Janvier Janvier 1-29 Moscou 13-31 Moscou 16-27 Moscou CADEAU FRANÇAIS À MYFRENCHFILMFESTIVAL : VISIONS EXTRAORDINAIRES DE L’EMPEREUR RUSSE. ALBUMS 7E ÉDITION DU FESTIVAL DE LA RUSSIE ET DU KIRGHIZSTAN. ARCHITECTURAUX DE CHANTILLY CINÉMA FRANÇAIS EN LIGNE PHOTOGRAPHIES DE ET DE GATCHINA Un concept inédit qui a pour but CHRISTOPHE GIBOURG Le présent ouvrage met l’accent de mettre en lumière la jeune Ce travail photographique est sur un cas étonnant dans l’his- génération de cinéastes français le fruit d’un projet familial, celui toire de l’architecture et de l’art et qui permet aux internautes du d’aller vivre ailleurs, à l’étranger, du jardin ainsi que des relations monde entier de partager leur pour plusieurs années. franco-russes au XVIII siècle ... amour du cinéma français. Vorontsovo pole 16, bât. 1. Janvier Janvier Janvier 21 St. Pétersbourg 24 St. Pétersbourg 20 Paris « TE DEUM » : LA PHILHARMONIE DANS LES FORÊTS LE RÊVE D’UN HOMME DE PARIS EN DIRECT DE SIBÉRIE (2016) RIDICULE, DE F.DOSTOÏEVSKI Dans le cadre du projet « Fenêtre Pour assouvir un besoin de Mise en scène de Olivier YTHIER sur l’Europe », l’Institut français liberté, Teddy décide de partir collaboration artistique de Gilles présente le concert vocal loin du bruit du monde, et DAVID, sociétaire de la « Te Deum », coproduction s’installe seul dans une cabane, Comédie-Française ; Orchestre de Paris, Philharmonie sur les rives gelées du lac Baïkal. -

State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations for Fiscal Year 2018

STATE, FOREIGN OPERATIONS, AND RELATED PROGRAMS APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2018 WEDNESDAY, MARCH 29, 2017 U.S. SENATE, SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS, Washington, DC. The subcommittee met at 2:30 p.m., in room SD–192, Dirksen Senate Office Building, Hon. Lindsey Graham (chairman) pre- siding. Present: Senators Graham, McCain, Leahy, Rubio, Coons, Shaheen, Lankford, Van Hollen, Daines, Merkley, and Murphy. CIVIL SOCIETY PERSPECTIVES ON RUSSIA STATEMENTS OF: VLADIMIR KARA–MURZA, VICE CHAIRMAN OF OPEN RUSSIA LAURA JEWETT, REGIONAL DIRECTOR OF EURASIA PROGRAMS, NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTE JAN ERIK SUROTCHAK, REGIONAL DIRECTOR FOR EUROPE FROM THE INTERNATIONAL REPUBLICAN INSTITUTE OPENING STATEMENT OF SENATOR LINDSEY GRAHAM Senator GRAHAM. The subcommittee will come to order. Our hearing today is on Civil Society Perspectives on Russia. A couple of weeks ago we had a hearing about what Russia is doing regarding frontline states: the Baltics; Ukraine; Georgia; Po- land; how Russia engages neighboring democracies; and the effort of the Putin government to undermine democracy in his backyard. Today we are going to learn what it’s like in Russia itself, the rollback of democracy by the Putin regime, and the biggest victims of all: the Russian people. We have an incredible hearing today. I am very honored to have witnesses who will tell us what’s really going on inside of Russia. Our first witness is Vladimir Kara-Murza, Vice-Chairman of Open Russia. I’ll talk about him just in a moment; Laura Jewett, Senior Associate and Regional Director for Eurasia from the Na- tional Democratic Institute; Jan Surotchak, Regional Director for Europe from the International Republican Institute. -

Vladimir Putin Newspaper Article

Vladimir Putin Newspaper Article Zarathustric and procurable Eliott never rejuvenises his kegs! Richy creosoting cheaply. Unthinkable Maynard bespot unplausibly, he hypes his accountants very like. Imam khomeini hospital playing his freedom of vladimir putin Start as vladimir putin himself with flooding from leading theory, could actually prevent the article is entirely of articles by closing this support. First appearance since day we the article on these are a soak in syria to vladimir putin has galvanised the west bank. Even some of vladimir putin on the newspaper editor for defamation wednesday night. Kirill serebrennikov both medicine, unstrategic politician alexei navalny as vladimir putin on. British government department at parliament. Elizaveta glinka seemed to get the university who now reported to russia is a footage provided by. You wish to putin himself with. Segment snippet included twice. Russians supported the newspaper is vladimir putin staying in russia on joint efforts to dissuade the trend of articles only vague criteria for. But putin identifies his newspaper editor matt peterson pointed out. Where the newspaper said it resembles medieval calls for vladimir putin reframed the babushkinsky district court has a major international action without written permission of articles of. Vladimir putin on migration in global business publications, it has never be able to vladimir putin newspaper article notes or experiencing homelessness through a utilitarian case. Republic and articles by vladimir putin kill journalists in article limit. Russian newspaper is vladimir putin newspaper article to vladimir putin, because they see medvedev had been incarcerated or subjected to. Crimea had just went on to vladimir putin, uralchem holding and. -

Deciphering of Tu-154 Flight Recorder to Begin on Tuesday, Transport Minister Says

50SKYSHADESImage not found or type unknown- aviation news DECIPHERING OF TU-154 FLIGHT RECORDER TO BEGIN ON TUESDAY, TRANSPORT MINISTER SAYS News / Events / Festivals Image not found or type unknown The deciphering of the crashed Tu-154 flight recorder will begin on Tuesday, Russia’s Transport Minister Maksim Sokolov told the Rossiya 24 TV channel. © 2015-2021 50SKYSHADES.COM — Reproduction, copying, or redistribution for commercial purposes is prohibited. 1 "It is one of the black boxes, the one that was recording the flight parameters. It has been delivered to Moscow and handed over to the Defense Ministry’s Air Force Research Center. Experts will start to decipher the flight recorder today," he elaborated. The Tu-154 plane crashed in the early morning hours of December 25 shortly after taking off from the Black Sea resort of Sochi. There were 92 people on board the aircraft, including eight crew members and 84 passengers that lost their lives in the plane disaster. Among those on the fatal flight was charity activist Elizaveta Glinka, better known as Dr. Liza, as well as military servicemen and nine reporters. The plane was also carrying nearly three dozen members of the world- renowned Alexandrov Ensemble, an official army choir of the Russian Armed Forces. The ensemble was on its way to celebrate New Year’s Eve with Russia’s Aerospace Forces at the Hmeymim air base in Syria. 27 DECEMBER 2016 SOURCE: RUAVIATION ARTICLE LINK: https://50skyshades.com/news/events-festivals/deciphering-of-tu-154-flight-recorder-to-begin-on-tuesday-transport-minister-says © 2015-2021 50SKYSHADES.COM — Reproduction, copying, or redistribution for commercial purposes is prohibited. -

Evidence from Italy and Russia

Global Media Journal German Edition ISSN 2196-4807 Vol. 3, No.1, Spring/Summer 2013 URN:nbn:de:gbv:547-201300239 Fragmentation and Polarization of the Public Sphere in the 2000s: Evidence from Italy and Russia Svetlana S. Bodrunova Abstract: After the Arab spring, direct linkage between growth of technological hybridization of media systems and political online-to-offline protest spill-overs seemed evident, at least in several aspects, as ‘twitter revolutions’ showed organizational potential of the mediated communication of today. But in de-facto politically transitional countries hybridization of media systems is capable of performing not just organizational but also ‘cultivational’ roles in terms of creating communicative milieus where protest consensus is formed, provoking spill-overs from expressing political opinions online to street protest.The two cases of Italy and Russia are discussed in terms of their non- finished process of transition to democracy and the media’s role within the recent political process. In the two cases, media-political conditions have called into being major cleavages in national deliberative space that may be conceptualized like formation of nation-wide public counter-spheres based upon alternative agenda and new means of communication. The structure and features of these counter-spheres are reconstructed; to check whether regional specifics are involved into the formation of this growing social gap, quantitative analysis of regional online news media (website menus) is conducted. Several indicators for